The greatest comics of all time don’t appear on bestseller charts or canon lists or big-box bookstore shelves. They are the property of the back issue bins and thrift store crates and convention hawkers of America, living like the medium itself in the unseen crags and pockets of publishing history…

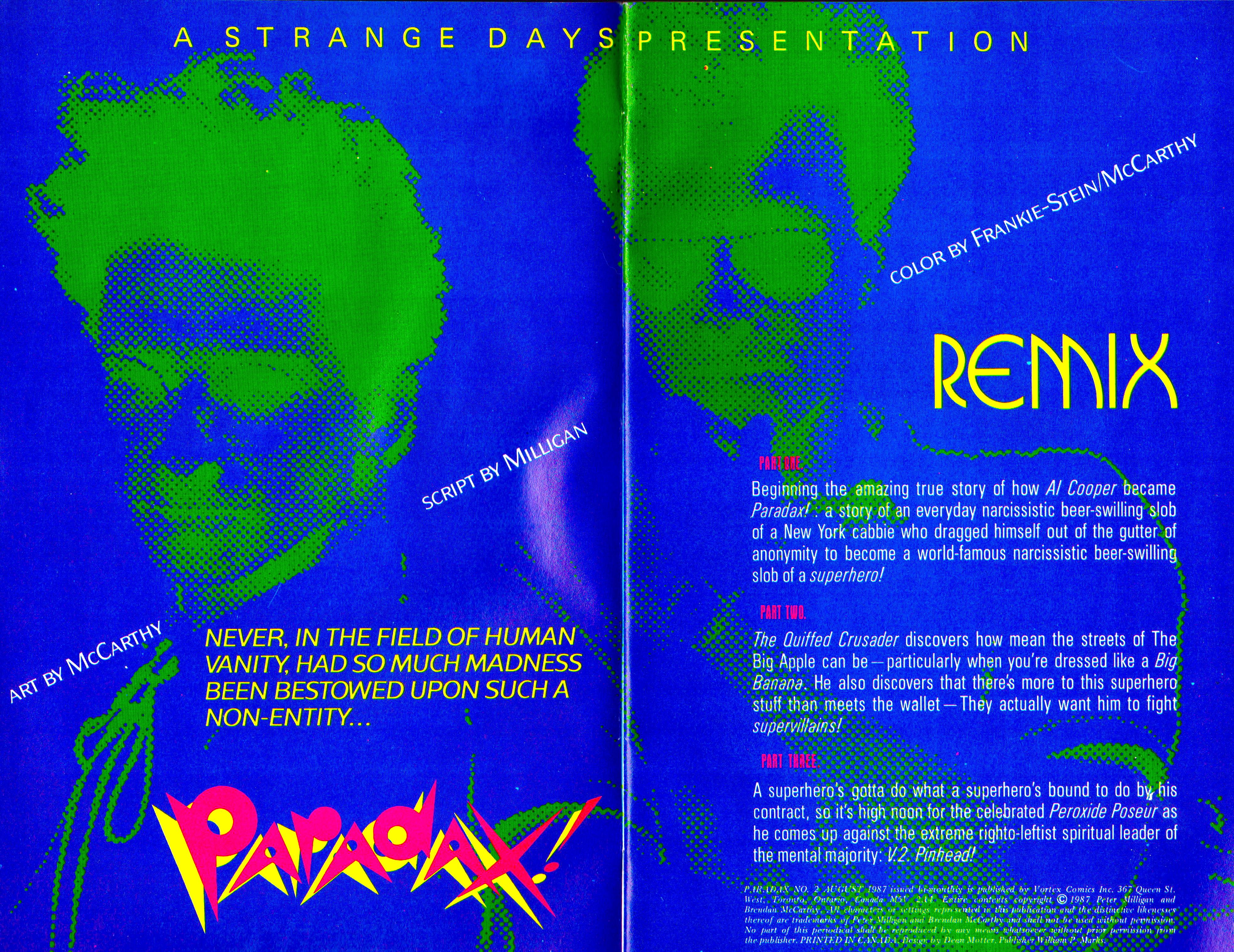

Paradax! Remix, drawn by Brendan McCarthy, colored by Frankie Stein and McCarthy, scripted by Peter Milligan. Cover-dated August 1987. Published by Vortex Comics.

How acquired: As a major proponent of old-school analog back issue hunting, it pains me to admit that everything leading to my ownership of this comic happened online. Brendan McCarthy is one of a very few great cartoonists whose complete works can be feasibly tracked down by normal dudes with rent to make and girlfriends' acting classes to pay for, and having decided to become one such dude, I used the unofficial guide that can be pieced together from this Comics Comics Magazine comments thread as a road map for a shopping spree at an online back issue retailer. Two weeks later a box of McCarthy comics, including this one, showed up.

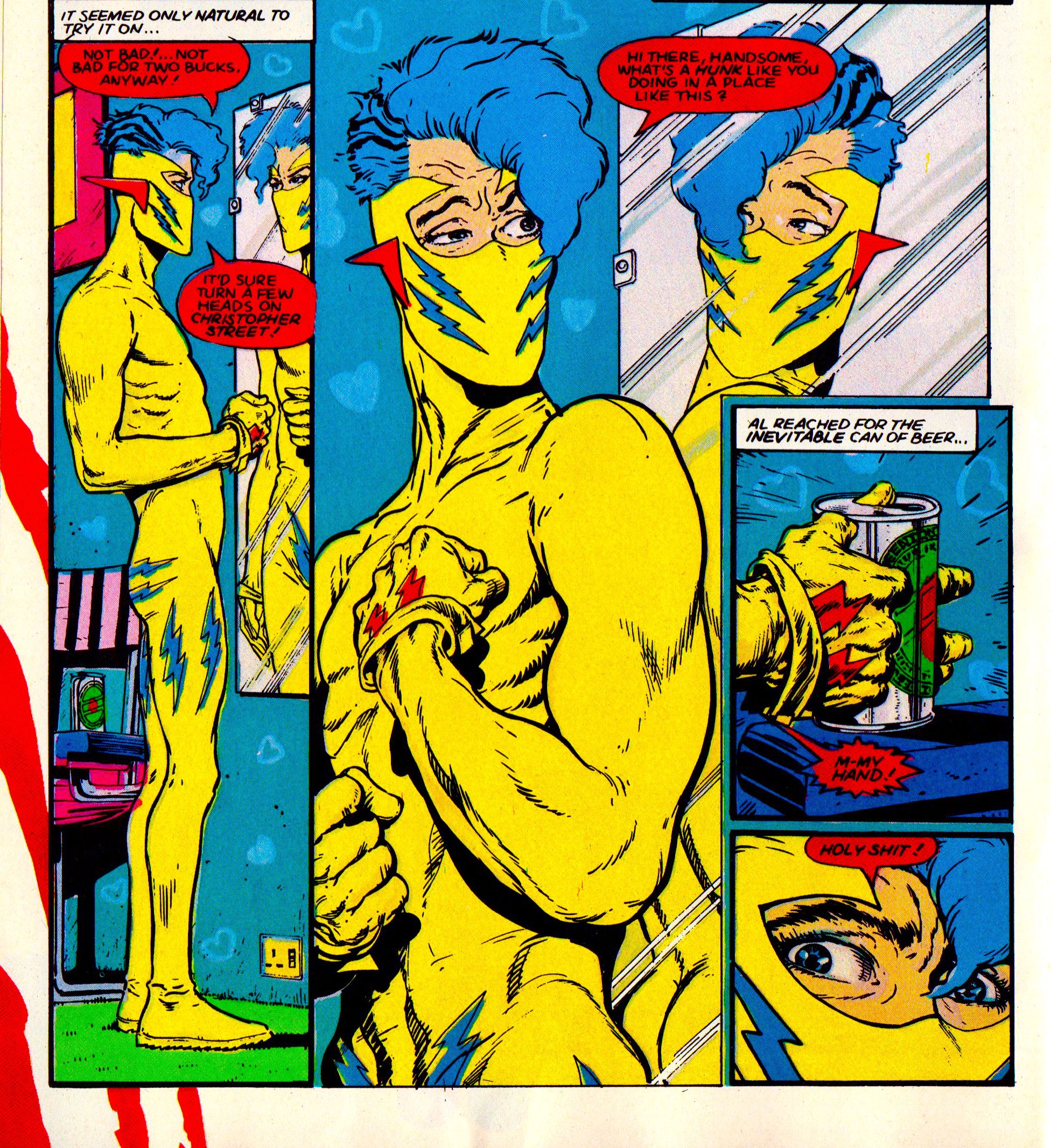

Best single drawing:

Color -- more interesting than line art since 1897!

The history lesson: As great a comic as Paradax! Remix is (the greatest, in fact, of all time), the most immediately arresting thing about this 32-page pamphlet is the stuff that isn't comics. Paradax! emerged from a wild context, and it's hard not to marvel at how exciting 1987 on the fringes of the medium's mainstream seems 25 years later. The opening spread features not the title character, or any story material at all, but a vanity shot of McCarthy and Milligan in technicolor screentones. The house ads for other Vortex comics are uniformly beautiful, and the comics they shill -- Chester Brown's Yummy Fur, Howard Chaykin's Black Kiss, Dean Motter's Mr. X -- make it seem in retrospect like this Canadian boutique imprint was one of the all-time great comic book publishers. The cover's black linework almost completely washed over by a drab teal-gray tone, with the hero's name printed in a cerulean barely distinguishable from the background -- the subtitle, REMIX, printed in hot pink, and the creative team's names in neon yellow are the most arresting things about the image. As a whole, it feels like an assault on the conventional wisdom about how a superhero comic should present itself.

Because yes, this is a superhero comic, and one of the most significant of the last post-Alan Moore quarter century. As the title implies, the actual comics in Paradax! Remix appeared before, elsewhere, in a similar form. This comic collects the three Paradax! shorts from McCarthy, Milligan, and artist Brett Ewins' psychedelic Britcomics anthology Strange Days (1984), packaging the continuing saga together into a single book-length comic. Remix is technically the second (and last) issue of the Paradax! series proper -- the overly muddled issue #1 picks up where the Strange Days material left off -- resulting in the mind-bending scenario of a serial whose final installment's end leads directly into its opening issue's beginning.

The draw here, in a comic which technically features no new story material, is McCarthy's recoloring of the original Paradax! stories, which were capably if conventionally hued by 2000AD stalwart Tom Frame. It's certainly a historical curiosity -- how many other comics use the color as their main selling point? -- but it also transforms what was merely an interesting footnote to the mid-'80s expansion of the superhero concept into a brightly glowing exemplar of hero comics that even today feels utterly modern. In a genre whose chief concern is keeping a handful of decades-old trademarks commercially viable, that's no small feat. Let's go to the tape!

Why it's the greatest comic of all time: It's impossible to ignore the moribundity of superheroes if you read enough of the comics that feature them. So many of the genre's classic texts, from Watchmen and Dark Knight right on through Kingdom Come and All Star Superman, obsess over aging, death, and obsolesence. It often seems necessary to go back over the decades to the wellsprings of stories about masked men in tights -- Kirby, Eisner, Infantino, Hanks -- to find a superhero comic with anything resembling a youthful energy to it. This void is exactly what Paradax! appeared on the scene to fill. The book's creators say it best in their introduction:

"Never before had there been a superhero as good-looking, self-centered, irreverent, and, though we say it ourselves, likeable. Even though (Paradax) is a superhero, he'll still be an ordinary guy, with more looks than brains, with no taste for heroism but plenty for beer and infidelity... both a product and a reflection of this era. His first thoughts upon gaining preternatural powers is not how he can fight crime and make the world a better place, but how he can really have a good time and become rich and famous and sought after."

Paradax, basically, is the first and only hipster superhero, complete with skinny jeans, ill leather jacket, wrecked NYC apartment, and Debbie Harry-looking girlfriend. Whether or not you personally resemble him, he's unmistakably the kind of dude who comes a dime a dozen in this world, one where the Clark Kents and Barry Allens are more or less impossible to find nowadays. Paradax is not a paragon of virtue, but of character, likeable not because of his moral convictions but simply because he's a cool guy. After finding a McCarthy-designed suit that resembles nothing more than a smart new wave update of the Flash's costume in the back of his taxicab, Al Cooper first contemplates becoming a criminal ("in a couple of days I'd be a rich as Michael Jackson!"), but decides, like any of us would, that a life of super-crime would be way too big a hassle, and resolves instead to call himself a hero and ride the media machine to stardom. First stop: an appearance on Andy Warhol's cable-access talk show.

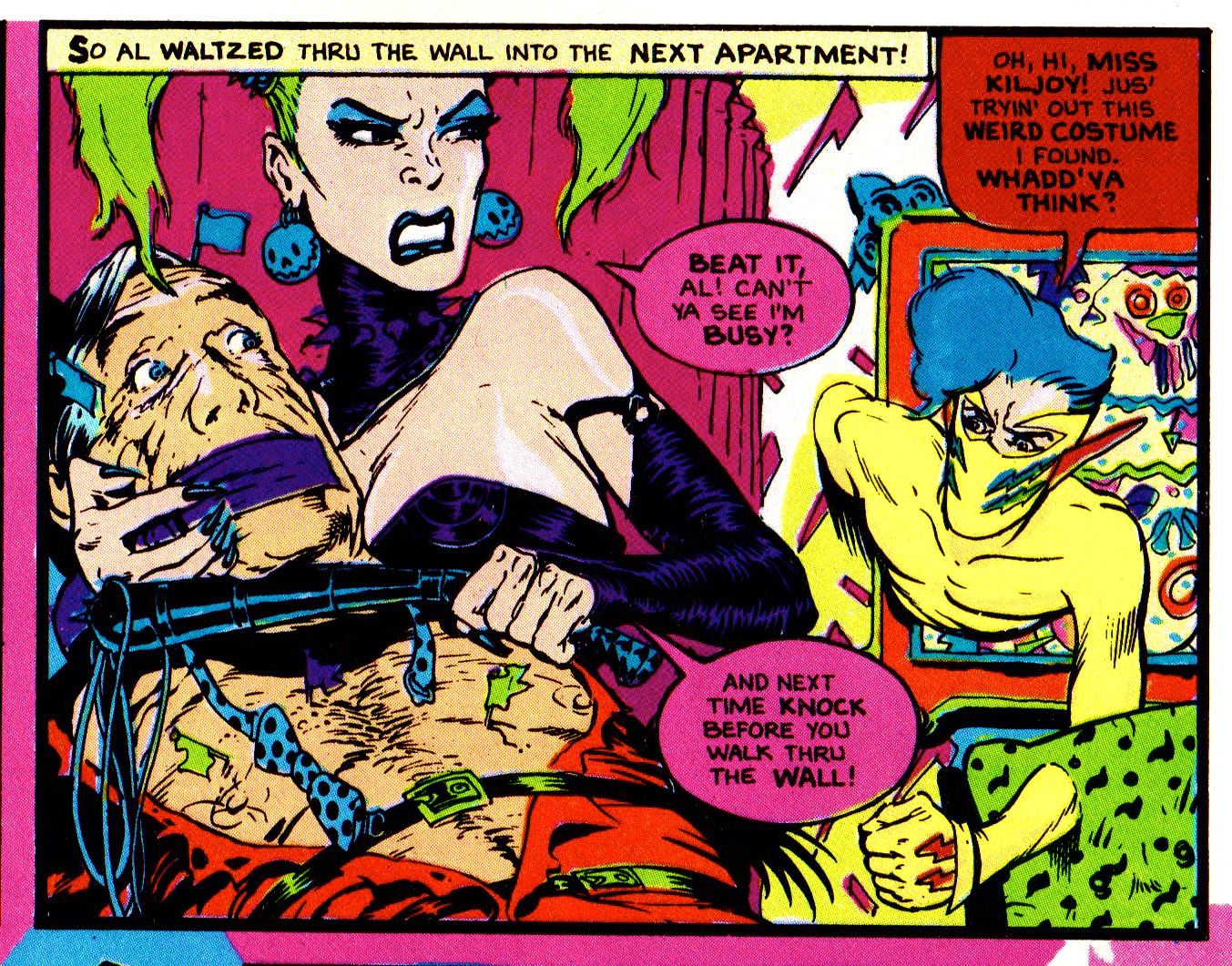

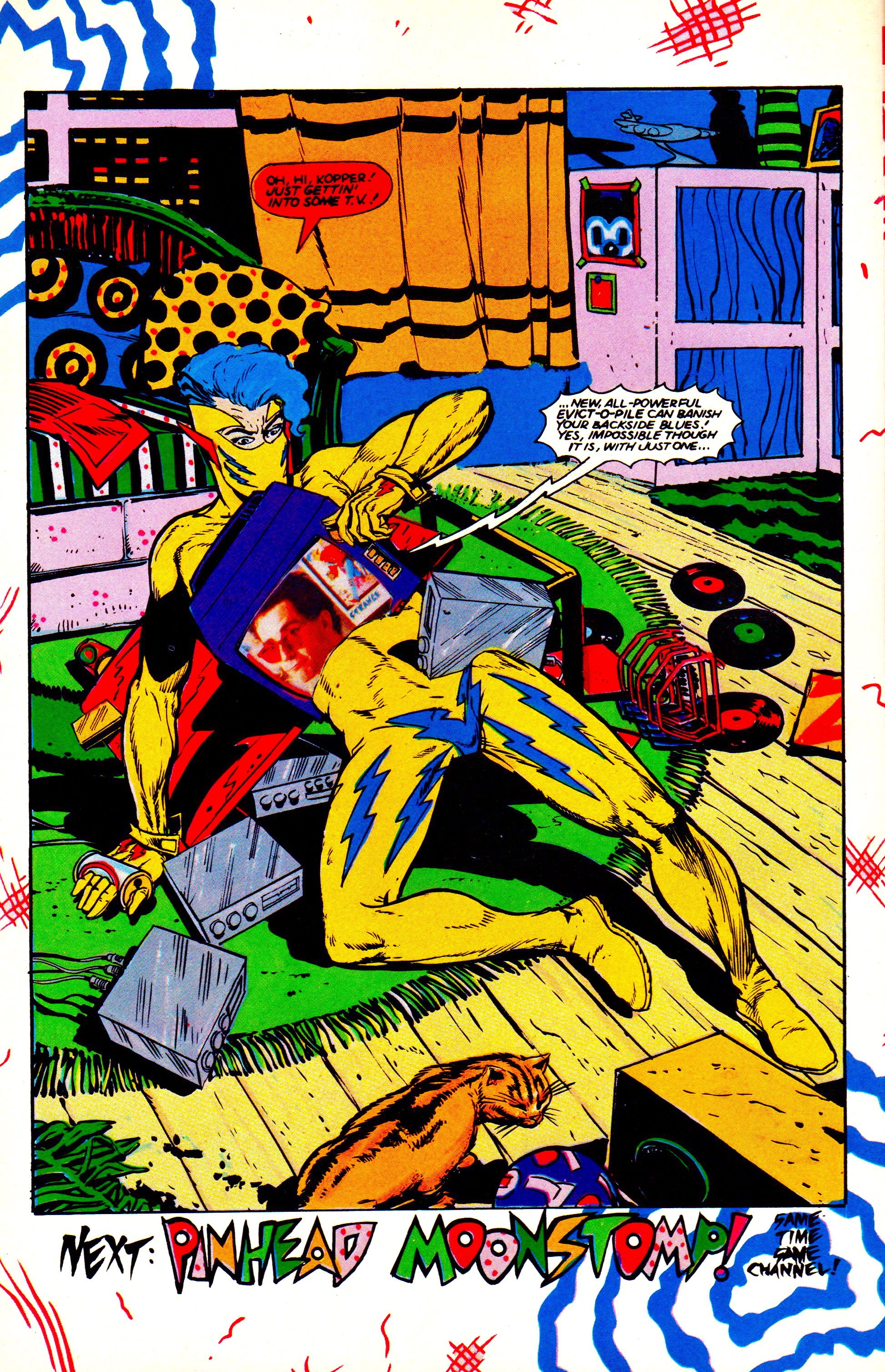

It's a small moment of decision, half a page among much bigger things, but it's the key to the entire concept, the peculiar genius of this comic: the aggrandized vacillations between Good and Evil we see the newly powered go through in every other superhero comic are overly simplistic, strangely over-moral lies that completely overlook the basic position of humanity. Paradax, like the rest of us, wants as much as possible for as little as possible, and this issue's big conflict only occurs when the cops assume the new hero might want to actually fight some villains. (Not the case, of course -- would you?) In McCarthy and Milligan's hands, the life of a New York City superhero is not much different from that of a somewhat notorious singer or painter, with a spandex costume added in: more drinking than sex, more sex than TV appearances, and more TV appearances than fights. It's only after awhile that one realizes Paradax is a character who'd be worth reading about even if he never faced off against a villain at all.

Paradax! is a comic of shallow pleasures and surface appeal -- like all superhero comics, really, but this one's honest about it. Hence the role of the artist is spotlighted, rather than sidelined and de-emphasized. Much as Milligan's script does to sell the strange circumstance of a legitimately normal guy who becomes a superhero (or a superhero who happens to be a legitimately normal guy), the concept would be on shaky ground indeed without a solid visual grounding. McCarthy sells Paradax's world perfectly -- no surface is uncluttered or plainly colored, no background anything less than bursting with electric blue hearts or evergreen exclamation points or blood red lightning bolts, no figure without its peculiarities of anatomy. The idealized superhero-comics body is completely out the window here: the hero's skinny, his girlfriends breasts are small, the villain's body lurches around like that of a drunken wrestler, and Paradax's two business managers are disgusting tubs of lard. And yet McCarthy's art still hadn't gone as far into pure psych and uninflected line as it eventually would: what muscles we see are illustrated with a feathering line that goes all the way back to Alex Raymond, and when the leads aren't drunk and lying seminude on the couch their poses are dynamic and decisive. McCarthy walks the line between the everyday and the fantastic in every panel, isolating the most visually exciting aspects of both.

As advertised, though, the colors are what make this comic. Given the opportunity to go for broke over years-old line art that he had long since surpassed, McCarthy drenches page after page in day-glo tones that scream into the reader's eyes, more vivid than anything real life can muster up. Jolly Rancher hues bleed into the traditional preserve of white space, the word balloons, and new wavey design elements -- stars, polka dots, parallel lines, abruptly shaped color fields -- take up the gutters between panels. It's more than a virtuoso performance by one of comics' all-time innovative colorists, it's a storytelling tool in and of itself: with no dead space left on any page to relax in, the eye is buffeted along further and faster until it arrives, exhilarated, at the comic's end. In Paradax! Remix, the fundamental tenets of superhero comics are no longer truth, justice, and the American way: they are finally acknowledged to be we really come for, bright colors, sexy thrills, and stories about dudes we all wish we could have lives a little bit more like. Is it any wonder that the superhero industry is in decline? The blueprint to follow was laid down years ago, and somehow nobody realized it. With every passing year and every depressing sales report, Paradax! Remix shines a little more brightly and looks a little more like the right path never taken.

Cover price: A cool $1.75.