Having thoroughly revolutionized superhero comics and after leaving a lasting mark on the medium as a whole, Grant Morrison is returning to his roots: being deliberately provocative and offending everyone. The man who DC trusted all of its big names to, who was tasked with rebooting the origin story of Santa himself in BOOM!’s “Klaus,” just announced his newest story for “Heavy Metal," the iconic French publisher for which he recently took over as editor. The name of this new serial? Why, “Savage Sword of Jesus Christ,” naturally!

RELATED: The 15 Most Controversial Marvel Stories Ever

Equal parts “Conan” and New Testament, Morrison’s collaboration with artists the Molen Brothers apparently involved a lot of academic research into the more esoteric areas of theology. So he says, anyway. Of course, this isn’t the first time the avant-garde comics scribe has been deliberately provocative in his art. For all his referencing of Kabbalistic texts and William S. Burroughs, he can’t resist some “South Park”-style controversy. Looking back across his career, controversy is something for which he has a unique flair. With that in mind, here's a selection of the most controversial comics throughout Grant Morrison's storied career.

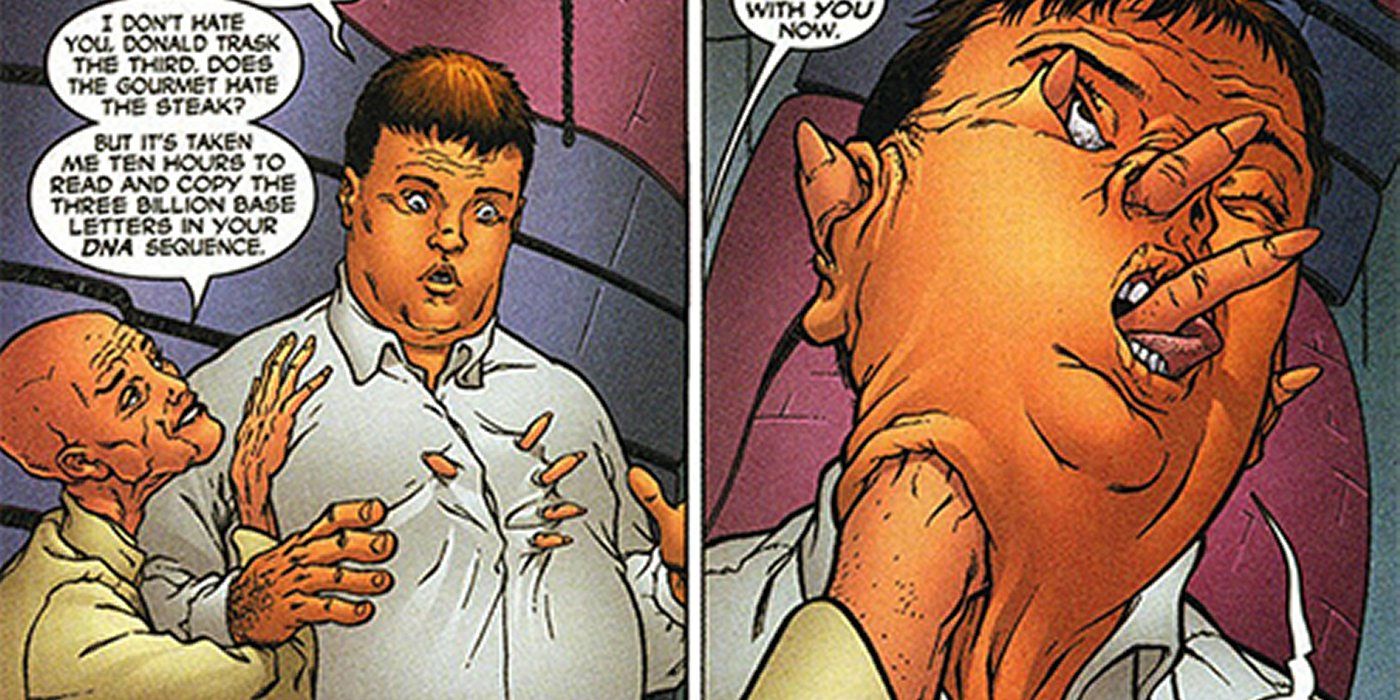

16 New X-Men

Tapped to bring the X-Men into the 21st century after the success of their big screen debut, Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely were given total access to Marvel's mighty mutants. However, they found that this playground soon turned into a prison. Quitely’s glacial work pace necessitated a succession of fill-in artists, while Morrison struggled with editorial interference by Marvel's former Vice President, Bill Jemas, as well as fandom's critical reception of his work.

"New X-Men" had plenty of plot twists that shocked readers, including the reveal of Xavier’s evil sister Cassandra Nova, thought killed in the womb, and the addition of “secondary mutations." Ultimately, it was the run’s conclusion that riled fans up the most. As it turns out, Magneto was behind everything all along! Again! Not only that, but Morrison made the villain a demented drug addict, in sharp contrast to his usual dignified depictions. The art was subject to significant online backlash, to the point where Croatian artist Igor Kordey all but abandoned American comics work entirely after having been rushed by Marvel editorial to meet impossibly tight deadlines.

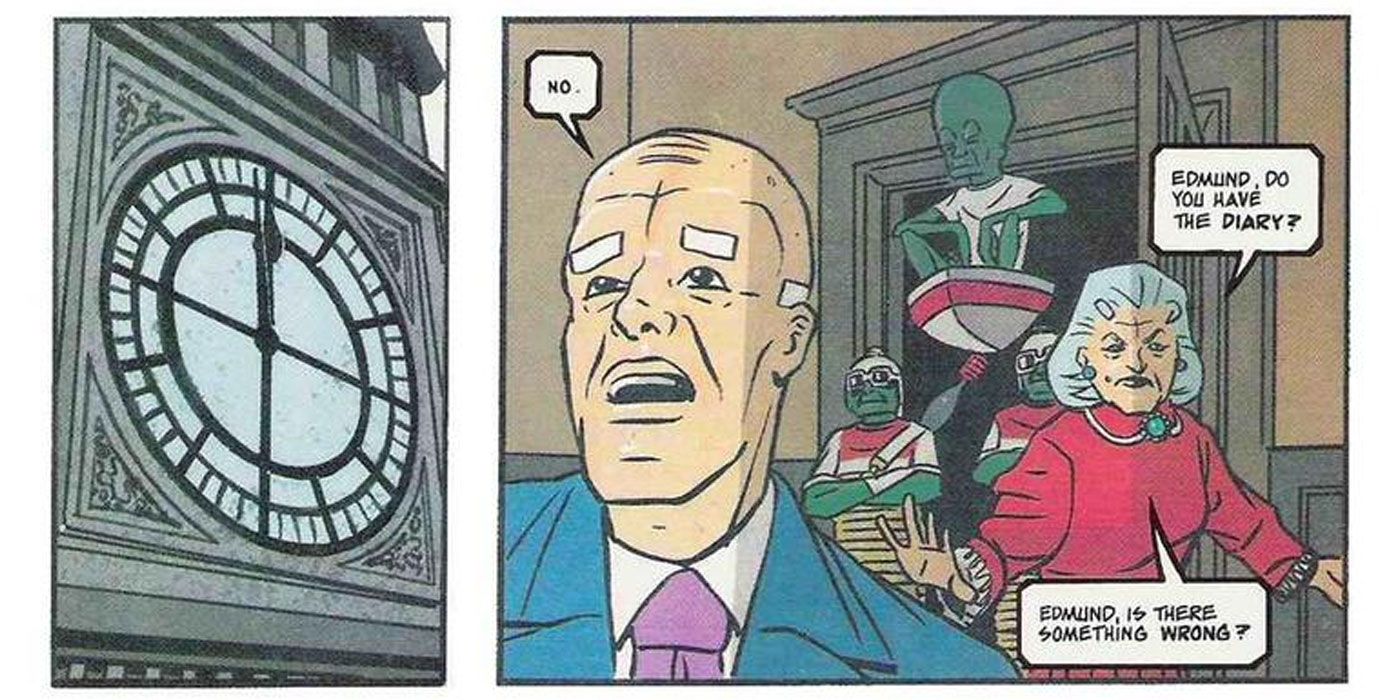

15 The Controversial Memoir of Dan Dare

It’s right there in the title! “Dan Dare” is an icon of British comics, one who never quite made it across the pond. The "Pilot of the Future" has been going on Buck Rogers-like adventures since the '50s, moving from children’s periodical “Eagle” to “2000 A.D.” and recently to a revisionist take by Garth Ennis and Gary Erskine for Virgin Comics; but Grant Morrison and Rian Hughes got there a few years before them.

The short-lived “2000 A.D.” spin-off “Revolver” carried Morrison and Hughes’s “controversial” take on the character. While he was originally based on the high-flying heroes of old war films, with plenty of post-WWII patriotism to go with his sci-fi adventures, the context of this new “Dan Dare” shifted to the Thatcherite politics of contemporary Britain. Instead of the usual examples of sci-fi derring-do, this Dare struggled with a privatized space fleet, the Venusian alien Treens were subject to racist abuse in ghettos, and everything got so hopeless that long-time supporting character Professor Peabody killed herself. The series ended with Dare destroying London in a suicide (nuclear) bombing. So, this wasn't exactly a "feel-good," and left a lot of old fans quite hollow, both on the story and towards Morrison.

14 Kid Eternity

Much like the revisionist history applied to “Dan Dare,” Morrison’s take on “Kid Eternity” with Duncan Fegredo added a lot of darkness to the character. The original Kid was killed during a U-Boat attack in World War II, only to be resurrected by accident and imbued with superpowers. He was allowed to continue his second life in exchange for fighting for good. It was wholesome fun for the whole family.

Right from the word "go," Morrison and Fegredo were twisting things into a much more disturbing shape. In their version, the orphaned Kid had been killed while aboard a shipping boat with a predatory “grandpa” figure who had adopted him. His return as a superhero proved to be no less troubling. The original Kid Eternity’s powers involved being able to call down any historical figure, real or fictional, to apply their particular skills to a situation. In the new “Kid Eternity,” these figures were revealed to be demons in disguise, with the whole thing being a plot by the Satanic Lords of Chaos to earn their ways back into heaven. It was all a far cry from the DC hero’s innocent origins and, while enjoyed by many, left others with a bad taste in their mouths.

13 Gideon Stargrave

He later became a key member of “The Invisibles” cast, but Gideon Stargrave’s origins go back a lot further. His first published appearance was in a story Morrison wrote and drew for a Scottish sci-fi anthology in 1978, just one of many he penned during his teenage years. Stargrave was, in many ways, Morrison's introduction to the comic industry.

He’s also ripped off wholesale from prolific British sci-fi author Michael Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius. Both are “ruthless yet likable dandy assassins,” as Morrison himself put it in an early “Invisibles” letters page. Despite all but admitting to the theft, Moorcock was outraged about Morrison lifting his work so blatantly. It transpired that, as well as inspiring the character, entire lines of dialogue in “The Invisibles” were taken, word-for-word, from his 1981 Cornelius novella “The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle.” “I never take legal action,” Moorcock later said in an interview. “It would be much cheaper to have GM duffed over... other comic people all generously acknowledge my influence, yet none of them have ripped me off the way Grant Morrison has.”

12 Animal Man

Off the back of his groundbreaking work in Britain, Morrison was offered to pitch on a series for DC. With an encyclopedic knowledge of the publisher’s history, he plucked out “Animal Man” as a book ripe for revival. Keeping superhero Buddy Baker’s ability to befriend animals and temporarily mimic their abilities, the writer added a decidedly political angle to the character.

Morrison had become a vegetarian after watching “The Animals Film,” a 1982 documentary which included gory footage of meat processors and the inhumane treatment of animals in factory farming. Teamed with artists Chas Truog and Doug Hazlewood, Morrison’s new zeal for animal rights played into their characterization of Buddy and the storylines he featured in.

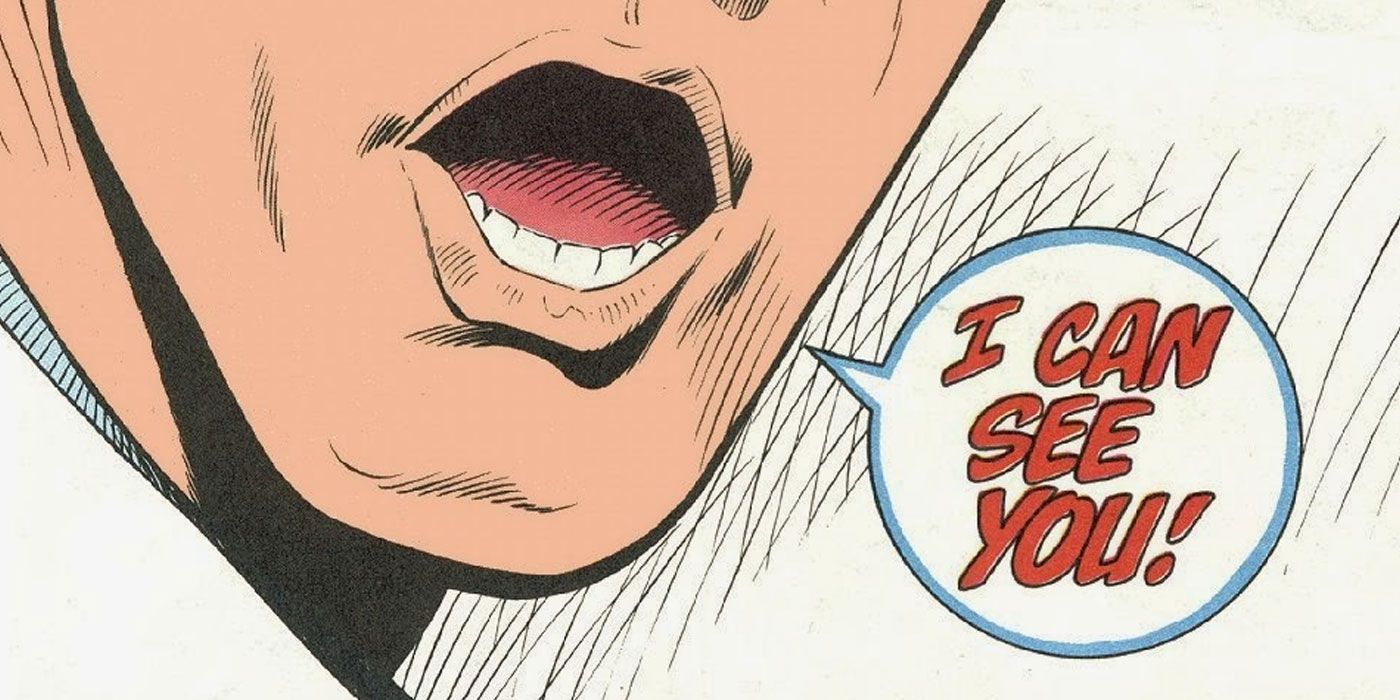

If that wasn’t enough of a shakeup, Buddy became aware of his nature as a fictional character, something that could be argued became a staple later in Morrison's career. Things got so meta at the end of “Animal Man” #19, that when the character turned to face the reader and exclaimed “I can see you!” Hazlewood fashioned Morrison a “paper avatar” as the writer entered the comic to address the character directly, a postmodern spin that put off those who hadn’t already dropped the book over the animal rights content.

11 Wonder Woman: Earth One

William Moulton Marston, creator of Wonder Woman, was an interesting man. Besides being behind one of the most enduring female superheroes in comics, he used the character to indulge his own predilection towards bondage, and as a mouthpiece for his opinions about gender (namely, that women should inherit the Earth).

Over the years, different creative teams have chosen to highlight or conceal those core aspects of the character to varying degrees. For the out-of-continuity graphic novel “Wonder Woman: Earth One,” Grant Morrison and Yannick Paquette aimed to return the character to her feminist origins. However, besides its all-male creative team, which many felt belied the impact of its boasted feminist credentials, the book was criticized for its less-than-progressive depiction of women throughout. Its themes of dominance and submission were also harder to take when it involved Steve Trevor, a black man in this version, washing up on the shores of Themyscira, clad in highly-symbolic chains; a potent image, perhaps, but also a very controversial one.

10 Doom Patrol

The self-proclaimed “World's Strangest Heroes!” were a natural fit for the world’s strangest superhero writer. Morrison and artist Richard Case took over from Paul Kupperberg and Steve Lightle on “Doom Patrol,” DC’s proto-X-Men who had started afresh in the wake of “Crisis On Infinite Earths.” The new creative team quickly set about making the team even stranger.

Working under the influence of postmodern literature by the likes of Italo Calvino and drawing directly from his own dream diaries, Morrison oversaw additions to the superhero squad including Crazy Jane, who suffered from multiple personality disorder, and a sentient, transgender road called Danny the Street.

The Dadaist sensibility was weird enough for a series that had begun as a standard superhero yarn. Those shaky foundations were utterly obliterated when Morrison and Case ended their run. In a final twist, it was revealed that the group’s de facto leader, “The Chief,” had orchestrated the accidents which had created much of the team (years before M. Night Shyamalan's “Unbreakable,” it should be noted), before he promptly tried to murder them all.

9 Flex Mentallo

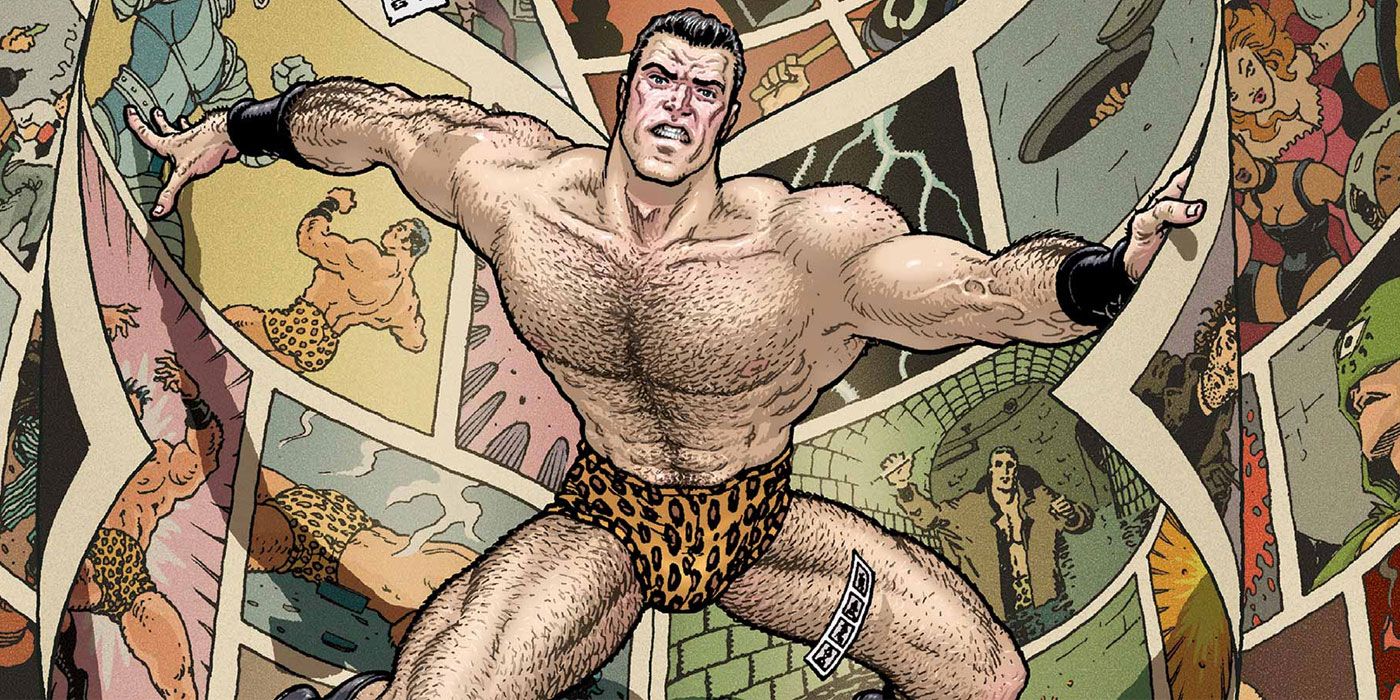

In pillaging the history of superhero comics for his work, Morrison sometimes strayed beyond the panel borders. “Flex Mentallo,” his first work with Scottish wunderkind artist Frank Quitely, was an attempt to lay the creative process out on the page. In it, readers get to see the true origins of the eponymous strongman character, as he climbed out of an old “Charles Atlas” advert.

The Atlas program was prominently advertised in comics from the '40s onwards, because the scrawny/overweight kids who were believed to have sought solace in funnybooks were the exact target audience for a fad bodybuilding scheme. Flex had the same built and leopard-print underwear as Atlas in his original “Doom Patrol” appearances, but showing his literal origin in the “Mentallo” series was a step too far.

A lawsuit filed by Jeffrey C. Hogue, president of Charles Atlas, Ltd., prevented the four-issue miniseries from being republished until 2012. By showing him arise from a recreation of the real Charles Atlas ads, it was argued, Morrison and Quitely violated copyright law. Years later, he would return to print after a long and bitter battle to have Flex’s appearance and origin ruled as a fair use parody of Atlas.

8 Batman R.I.P.

By the time Grant Morrison was done with him, the Dark Knight would have been ripped from his cowl, dumped on the streets and become addicted to heroin. The writer’s epic run on the main “Batman” books attempted to bring together all versions of the character -- from the goofy adventures of the '50s to the gothic realism of Neal Adams -- as equally valid, before completely dismantling him.

In the “Batman R.I.P.” arc with Tony Daniel, they also did what no member of the hero’s rogue’s gallery ever managed: they killed the Batman. Well... sort of. The story saw a criminal organization called the Black Glove, led by a villain called Dr. Hurt, who may have been either a resurrected Thomas Wayne or Satan himself, completely dismantle the Dark Knight’s life; “THE COMPLETE AND UTTER RUINATION OF A NOBLE SPIRIT,” in other words.

Having broken his psyche entirely, the Black Glove tossed a costume-less Bruce into a dumpster, where he quickly adopted the new identity of a homeless drug abuser. Obviously that didn’t last, but until Batman got back on his feet, Morrison was the target of a volley of death threats online.

7 St. Swithin's Day

Compared to some of the more out-there imagery featured in later Morrison work, “St. Swithin’s Day” is fairly grounded. Paul Grist, who would later find fame himself for his long-running small press works “Jack Staff” and “Kane,” illustrated this story that took place in the everyday quotidian environs of suburban Britain in the 80s.

The semi-autobiographical tale, based in part upon the diaries of a teenaged Morrison, follow an alienated teen who experienced the social injustice of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government firsthand. When he learns that the prime minister is due to make a public appearance at a local college, the nameless protagonist begins plotting to assassinate the Prime Minister.

Inevitably, that part of the story caused considerable controversy. A member of Thatcher’s party condemned the book, following a scandalized front page report by pro-Thatcher newspaper “The Sun.” All of this led to questions being asked about the story in the House of Commons, and Trident Comics quickly harnessing the publicity by widely advertising the collected version with prominently-placed ads in the very same paper.

6 The Filth

The third and final part of what Morrison calls his “hypersigil trilogy,” along with “The Invisibles” and “Flex Mentallo," “The Filth” certainly lives up its name. Owing to a period of depression following various personal tragedies, including the prolonged loss of a beloved pet cat to cancer, the Vertigo series is among the most nihilistic and profoundly disturbing books the writer has ever published, much of which is down to the wonderfully nasty and detailed artwork of Chris Weston.

However, even Weston was distressed by “The Filth” at times, exerting some artistic license in illustrating Morrison's scripts. The very first page was supposed to feature a far more graphic torture and violent death of a female character, before he toned it down. Weston illustrated the rest of the nightmarish imagery with a visceral, meaty weight, including the gigantic flying sperm of a porn director tearing apart civilians on Hollywood Boulevard, a misanthropic talking monkey with a gun, and a flying pleasure cruise that descended into a violent orgy of sex and death. "The Flith," as you might expect, was not exactly one for the kids, and almost wasn't one for its own artist.

5 Big Dave

Their career paths have diverged wildly in the interim, but Mark Millar and Grant Morrison wrote together on a number of their early professional projects. Their most well-known shared creation, with artist Steve Parkhouse, was “Big Dave” for “2000 A.D.” Controversy was the watchword in creating him, with the “hardest man in Manchester” tasked with beating up Saddam Hussein in his first appearance.

Dave was the product of an eight-week experiment, aptly named the “Summer Offensive,” where editor Alan McKenzie gave free rein to his subversive young creative teams. The second story ended with Dave in bed with Princess Diana, and a third saw him navigating a minibus full of disabled children to the World Cup so they could defeat a German national team inexplicably managed by Adolf Hitler.

Conceived as a satire of sensationalistic journalism, the character and his adventures divided “2000 A.D.” readers, who were unable to agree if it actually was a blistering critique of celebrity-obsessed culture or simply puerile rubbish. Dave has not appeared since his fourth and final story, “Wotta Lotta Balls,” perhaps unsurprisingly.

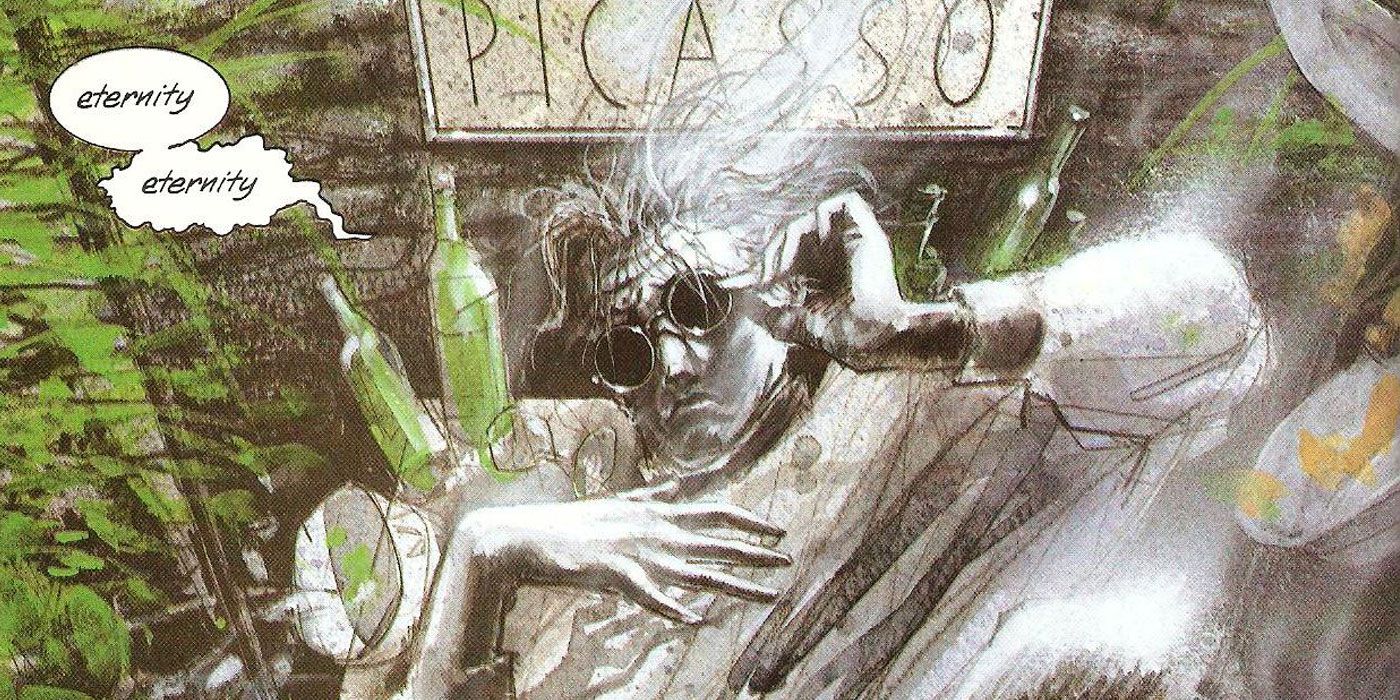

4 Really & Truly

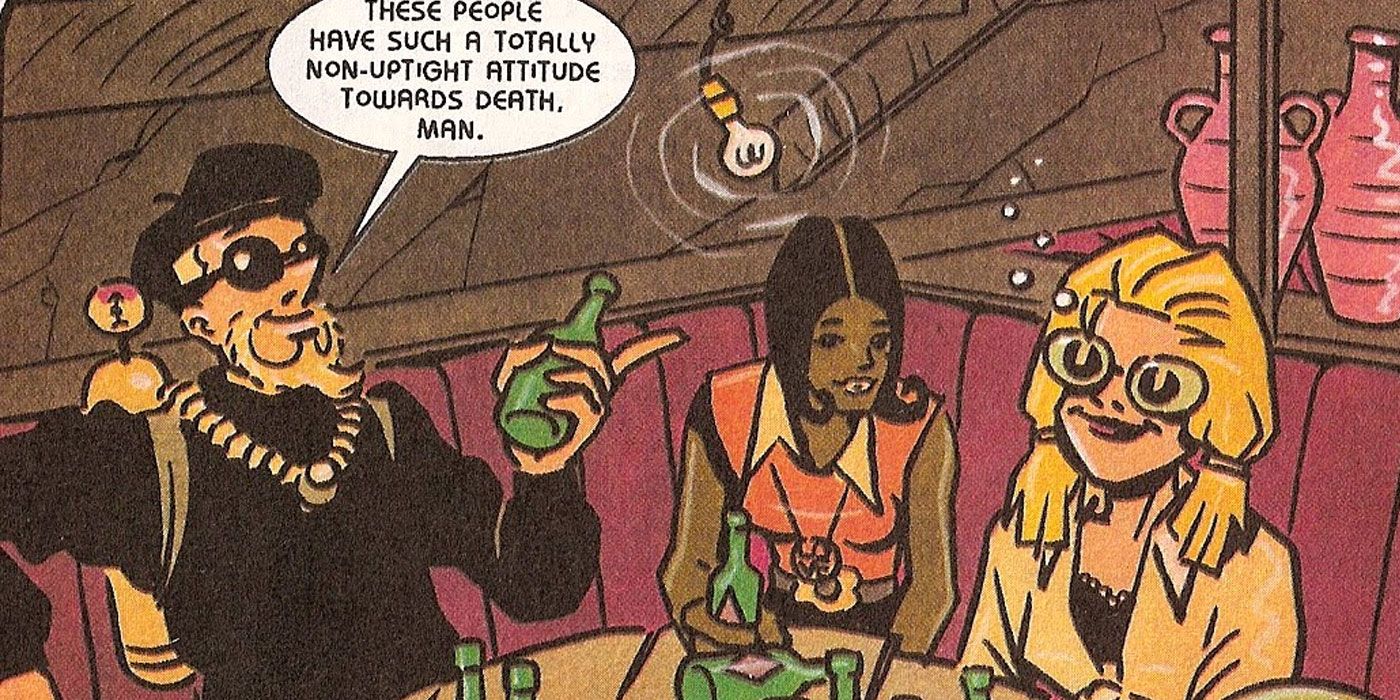

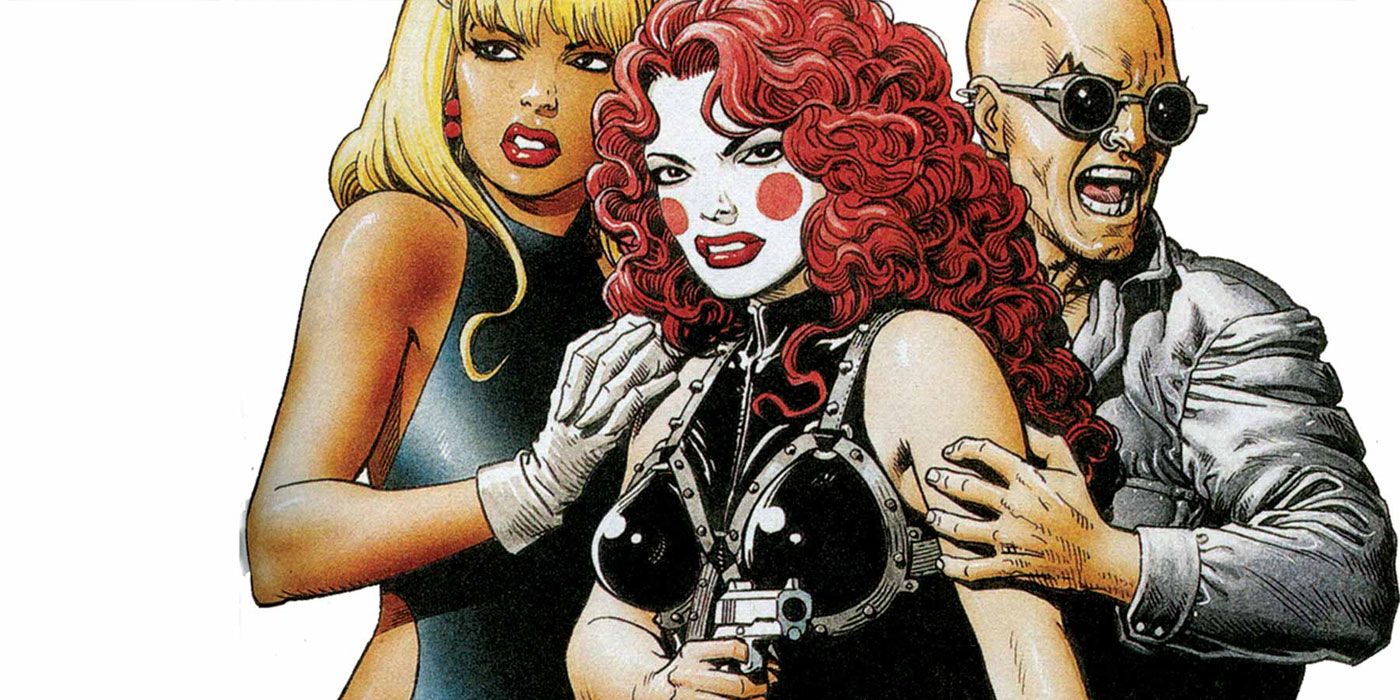

Morrison’s second contribution to the “Summer Offensive” drew similar influence from the British society around him. Illegal warehouse raves and the ensuant drug culture mixed with the feminist punk of riot grrrl to make a class-A “Josie and the Pussycats.” With Rian Hughes again on art duties, “Really & Truly” centered on the titular twosome of hard-partying women sent on a drug-running mission.

In fact, drugs were just part of their cargo, as they also had to deal with a shipment of weapons, as well as the safe delivery of two weirdos called Zhivago and Scuba Trooper. If it all sounds rather similar to Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett’s “Tank Girl,” which was running at around the same time, that’s because it was. The controversy this time wasn’t other plagiarism, however.

The explicit drug use of the characters was somewhat outrageous for “2000 A.D.,” as was the explicit drug use of Morrison himself. Allegedly, he was frequently high on the rave drug while penning “Really & Truly,” which might explain some of the harder-to-explain turns the plot took and the inclusion of a beatific pair of pursuers for the protagonists called Nice and Buddah.

3 The New Adventures of Hitler

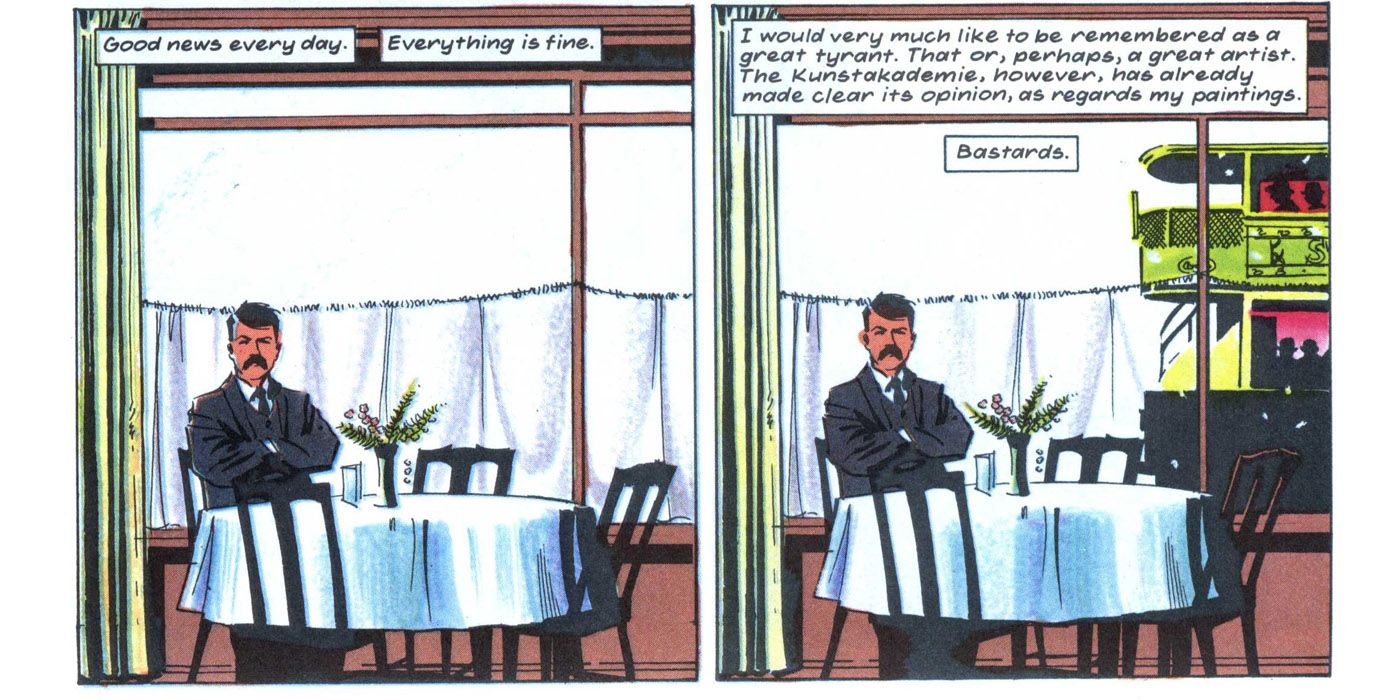

The germ of the idea which would become “Savage Sword of Jesus Christ” -- Nazi research into rebranding Jesus as a powerful Aryan -- originated in research Morrison was doing for this four-part story about Adolf Hitler. Originally published in Scottish magazine “Cut” with psychedelic collage art by Steve Yeowell, “The New Adventures of Hitler” saw the future fuhrer in the doldrums after his dismissal from art school.

He seeks solace with a trip to visit sister-in-law Bridget Dowling, who really did claim that Hitler lived with her family in Liverpool for a spell in the early 20th century. In their version of the story, Morrison and Yeowell depicted a hallucinatory journey where Adolf manipulates those around him whilst being plagued by visions of Margaret Thatcher and mopey indie heartthrob Morrissey.

During the initial serialization, one “Cut” editor threatened to quit, arguing publicly with Morrison over the content of the strip. Some accused the writer of being a Nazi himself, something which did not abate when English tabloid “The Sun” picked up the scandalous story when it was reprinted in “2000 A.D.” sister series “Crisis.” To this day, the short work remains uncollected in trade paperback form.

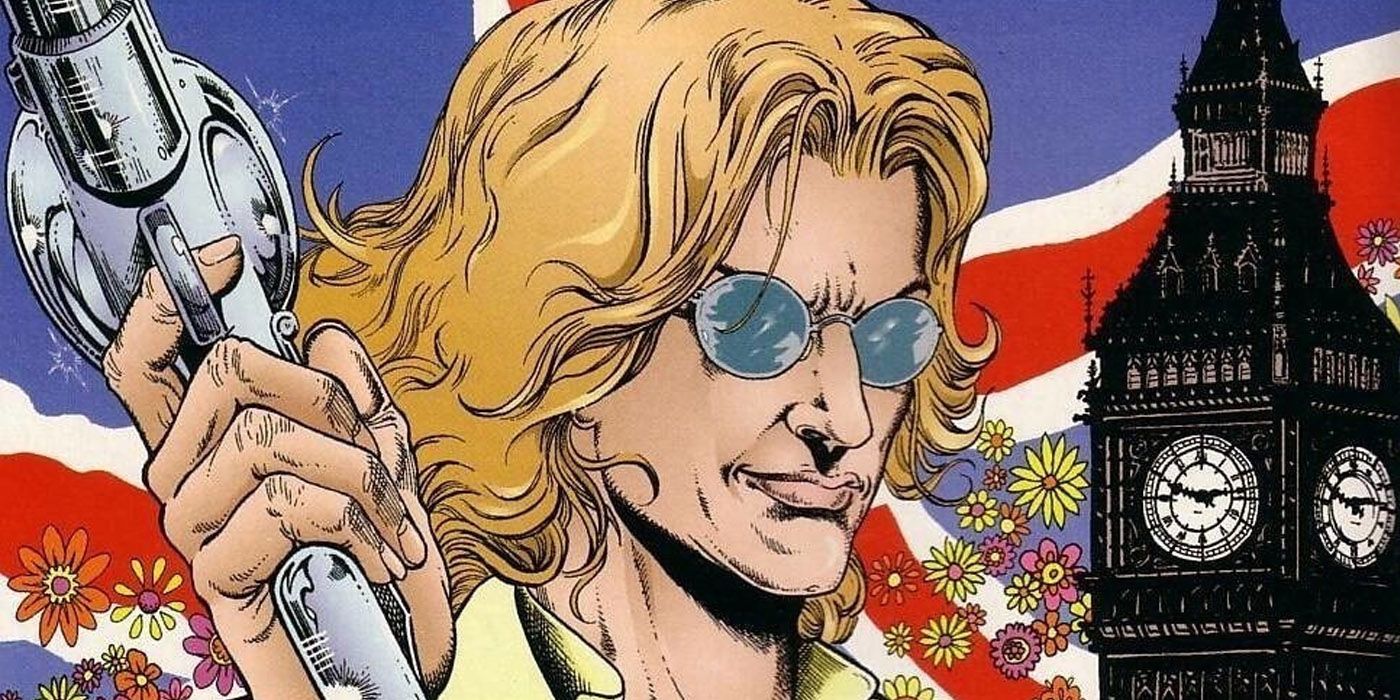

2 Zenith

A reaction against the wave of dour superhero stories following the publication of “The Dark Knight Returns,” Zenith was a hero for Generation X: stylish, shallow, glib and sarcastic. Despite his popularity at the time, the “Zenith” collections quickly fell out of print. Reprints of the story proved to be as controversial as Morrison's previous collaboration with Steve Yeowell, the aforementioned Hitler book.

The creators had long asserted their ownership of the character and the stories that featured him, whilst “2000 A.D.” publishers Rebellion claimed otherwise. In 2013, Rebellion began reprinting “Zenith” in limited edition hardback form, apparently without the blessing of the creative team.

The initial run had not been without scandal, either. As with much of his early work, Morrison used “Zenith” as a mouthpiece for his political opinions. Along with commenting on the state of British politics at the time, the “Phase II” story arc featured an antagonist very clearly modelled on entrepreneur Richard Branson. The resemblance between the Virgin founder and the media mogul, who, in the story, hoped to breed a race of super-people, was borderline litigious.

1 The Invisibles

“The Invisibles” opens with a character screaming the f-word. That was how Grant Morrison celebrated the untethered freedom he expected from writing a book for DC’s newly-minted Mature Readers line, Vertigo. As it happens, the constantly-changing creative team often pushed the boundaries of acceptability. The seventh issue saw the characters trapped in “120 Days of Sodom,” which led to censorship of references to child sexual abuse drawn from Marquis de Sade's novel.

Later issues saw the names of people and organizations blanked out after the advice of the publisher’s legal team. Dismayed though he was by the censorship, it’s nothing compared to how Morrison felt when DC’s parent company appeared to completely rip his creation off.

The Scottish writer recalls being taken to a showing of “The Matrix,” where he “saw what seemed to me my own combination of ideas enacted on the screen: fetish clothes, bald heads, kung fu, and magic.” While he never pursued serious claims against the Wachowskis, or anybody else involved in the production, he has expressed annoyance that his influence wasn’t even acknowledged; especially since sources told him issues of the book were strewn all over the film’s set.

What are some of your most memorably controversial Grant Morrison stories and/or books? Let us know in the comments!