Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, Volume 1

Written by Alex Raymond and Don Moore; Illustrated by Alex Raymond

Checker; $19.95

First, a warning. Reading Flash Gordon in its original Alex Raymond could very well make you hate other versions. Especially the crappy Sci Fi Channel series from a couple of years ago, but maybe even the Sam Jones movie from the ‘80s. The first Buster Crabbe serial holds up pretty well against it considering its effects limitations, but every other adaptation I’ve seen inexplicably waters down the crazy imagination that went into the original strips.

It’s not that it would be all that hard to adapt either. The story’s straightforward and Raymond even broke it up into convenient arcs that wrap up one part of Flash’s adventures before continuing on to the next. At the same time though, it’s not episodic. Each smaller story builds on the ones that have come before, so you could put a couple of them together to make a feature-length movie and they’d feel like they fit while still having a real ending.

I could go on about the right way to make a Flash Gordon movie (or TV show), but all I’m really trying to say is that this is a beautiful, inventive story and it’s a shame no one’s grabbed hold of what makes it that way when trying to translate it into other media. Actually, you know what? I will talk about that some more, because I think that’s a good way to talk about some of the elements in Flash Gordon; specifically, which ones still work for a modern audience and which would need updating.

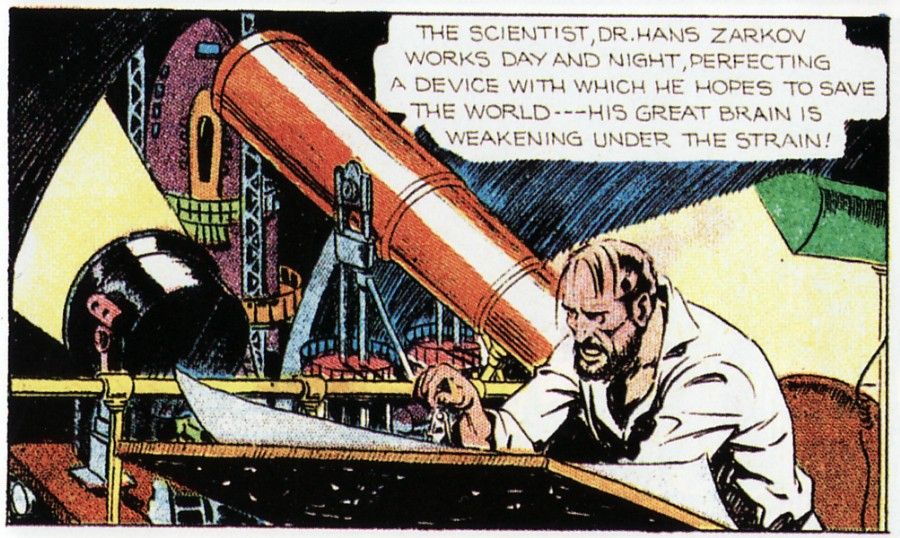

You’d have to change the “origin story” for starters. The first panel of the first strip is a newspaper headline: “Strange New Planet Rushing Toward Earth. Only Miracle Can Save Us, Says Science.” People around the world are panicking and Dr. Hans Zarkov is working around the clock to develop something to stop the coming doom. The strain, we’re told, is driving him mad.

Meanwhile, Flash Gordon (Yale graduate and world-renowned polo player) is on a plane with Dale Arden, who’s described merely as “a passenger.” We’re not told if they have any prior relationship, but that’s not supposed to matter because their lives up to that point are unimportant. What’s important is that a chunk of the runaway planet hits the wing of their plane and they have to bail out. The pilot (who’s never mentioned) presumably doesn’t make it.

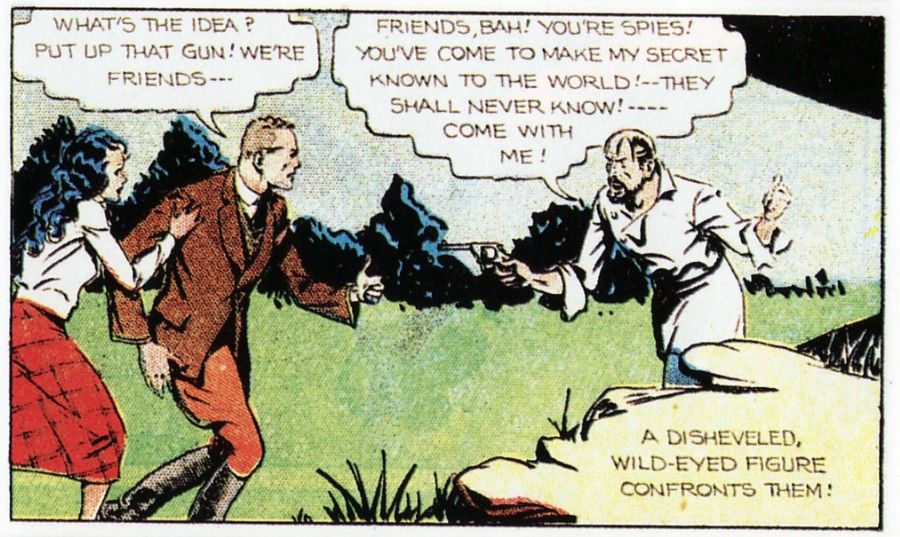

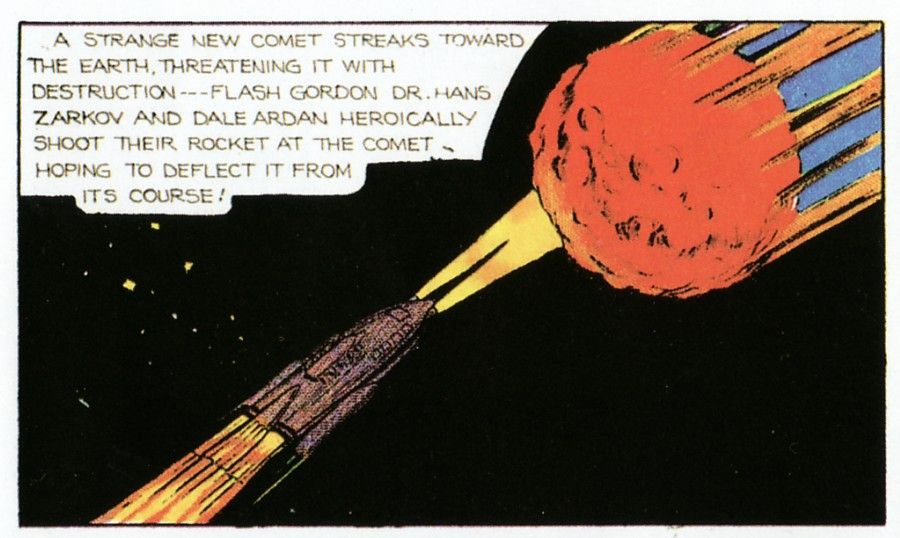

Flash and Dale land near Zarkov’s laboratory/observatory just as he’s getting ready to launch a rocket in hopes of hitting the runaway planet and deflecting it off of its course towards Earth. Unfortunately, he takes them for spies (“come to make my secret known to the world!”) and forces them on board the rocket. In all fairness, he’s going himself too so that all three of them will die as “martyrs to science.”

There’s obviously some updating that would need to be done here. An asteroid is not a runaway planet, and it’s especially not a runaway planet full of cities and complex civilizations as we quickly learn this one is. To make our hypothetical, modern movie, we need a modified version of these events (and I’ll suggest one in a bit here). Surprisingly though, a lot of the rest of the origin makes sense. I didn’t buy Zarkov’s actions at first, but thinking more about it, I can get what he’s up to.

His rocket would’ve been an enormous breakthrough in 1934. Assuming he’s loyal to the US, I can see why he’d not want the technology to fall into the hands of spies. Also assuming that he’s got to pilot the craft himself to make sure it hits the asteroid, I can see why the unhinged scientist would force the spies to join him on his suicide mission.

Where things go wrong again is in the next strip where the rocket crashes on the planet. Raymond’s inconsistent about the size of the world. In the first panel it looks like the diameter is roughly the same size as Zarkov’s ship. Four panels later, the ship is flying over a city before it hurtles into a small mountain and blows up. Even allowing for some wonky perspective in that first shot, there’s no way that asteroid’s big enough to hold even the mountain, much less the city (not to mention the countless other kingdoms Flash and his friends soon discover).

If this were Marvel in the '70s, I’d write in for my No-Prize with the possible explanation (borrowing the one good thing from the Sci Fi Channel series) that the asteroid somehow contains a wormhole. And that by going through it, Zarkov’s ship actually does prevent the asteroid from hitting Earth at the same time that the ship is transported to a larger planet.

It’s the only explanation that makes sense to me. Once Flash and Dale (they assume at first that Zarkov died in the crash) start exploring the planet, the danger to the Earth is forgotten. Not just by Flash, but apparently by Raymond as well. At least, it doesn’t come up again in the year-plus worth of strips in this collection. We have to figure that the Earth was somehow saved.

I won’t spend as much time on the rest of the book as I just did on the first two pages, and that’s kind of unfair because the rest of the book is awesome. Flash and Dale learn that they’re on the planet Mongo, that it’s ruled by the merciless Emperor Ming, and that it’s home to an apparently limitless number of monsters, alien races, and political factions. There’s enough adventure on Mongo to last a lifetime. It’s a great setting and though Raymond appears to exploit it fully, I kept getting the idea that he was only scratching the surface.

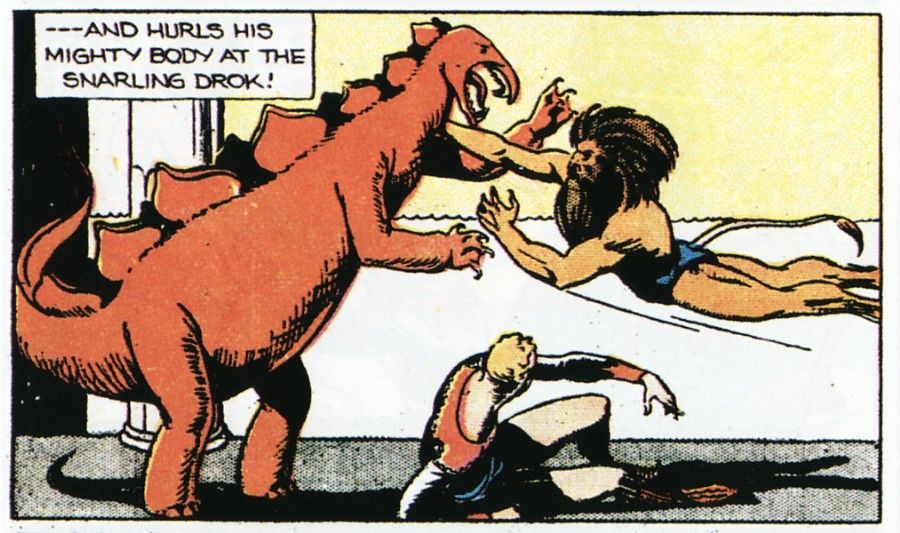

It’s because I enjoyed the rest of the book so much that I spent so much time thinking about and trying to justify the goofy beginning. Flash meets lion-men, shark-men, dragon-men, lizard-men, and of course the famous hawk-men. He fights giant reptiles, multi-headed beasts, dinosaurs, man-eating plants, and clawed, alien monstrosities. He fences (occasionally on tightropes over roaring flames), jousts, leaps out high windows, falls into deadly pits, and crawls through secret tunnels. All of which is gorgeously and convincingly drawn by Raymond. Mongo is a real place. You want to go there and Raymond lets you.

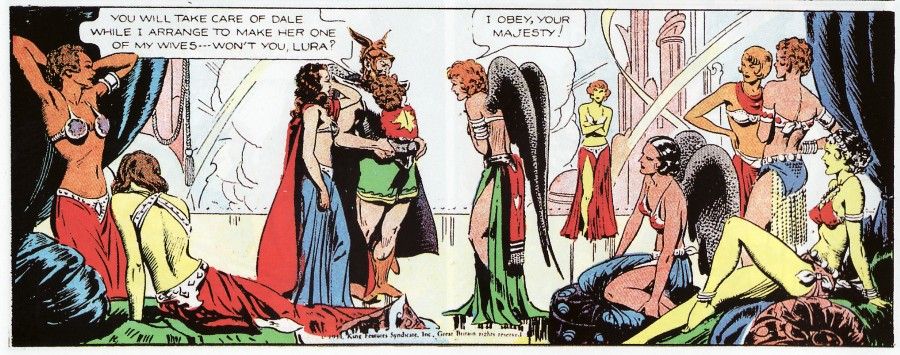

Checker’s Mark Thompson gives special praise in his intro to Raymond’s ability to draw women. Talking about the film versions he says, “They could never seem to find women who met the physical beauty that Raymond imagined.” That’s true and it goes for Ming’s daughter Aura as well as Dale. Meaning no disrespect to the actresses who’ve played those two characters, but Raymond’s versions are designed to make you fall in love with them at first look.

They kind of have to be though, because there’s not much else to them. A couple of other elements that would need updating in a modern-day Flash Gordon series are the roles of the women and some ethnic stereotyping (though the latter is much more restrained that I usually expect from stories of this era).

Dale exists solely to be rescued and to offer herself to villainous kings who want to kill Flash. I lost track of the number of times she agreed to marry someone in order to save Flash’s life. Her relationship with Flash also moves a lot faster than I can believe unless they were already heavily committed to each other when they were on that plane. It’s not long before they’re throwing their arms around each other and declaring their undying love. If I’m still going for my No-Prize, I’ve got to say that they were engaged before the story started. That’s not as much fun as it would’ve been to watch them become a couple during their adventure though.

Princess Aura – as is usually the case in the adaptations I’ve seen – is far more interesting than Dale. Aura’s her own woman with her own agenda. She plots her own plots and schemes her own schemes. Unfortunately they all revolve around either 1) getting Flash to fall in love with her, or 2) taking revenge on him because he doesn’t. There needs to be more to her than that.

I’d always heard that Ming was a twist on the typical Yellow Peril villain from the ‘30s and I don’t doubt that’s true. From his name to his yellow skin, he’s basically an alien Fu Manchu. Because I’ve only ever been exposed to later adaptations until now, I never realized that Ming’s skin was originally bright yellow. For all that though, I find myself cutting Raymond some slack. I don't know if I have a good reason or not, but Ming and his people don’t get my hackles up the way that – say – a lot of the Golden Age jungle comics do.

For one thing, while Ming and his lackeys are clearly evil world-conquerors, there are other members of Ming’s race who fight alongside Flash in hopes of overthrowing the tyrant. One of these is Prince Barin who’s always portrayed in the movies as a swashbuckling European. I was actually surprised to learn that he’s part of Ming’s race in the strips. What’s more, he’s probably the most complex character in the book. His trying to balance his lust for Aura (he calls it love; I disagree) with his loyalty towards Flash makes him hard to figure out. It’s no wonder the film adaptations have portrayed him in such radically different ways.

If Raymond is playing to Yellow Peril with Ming, he’s inconsistent about his applying the stereotype to other members of Ming’s race. That diversity in characterization makes me ease up on him. Not completely, but some.

Certainly more than I ease up on him for the brown-skinned race of “dwarfs” he throws in. These thinly disguised caricatures of African pygmies may be products of their times, but I don’t have to like them. Fortunately, they’re minor players in the book. Ming and his people are major characters and I have a hard enough time getting past them.

But… in our hypothetical new version, this is easily fixed. It has been easily fixed in pretty much every adaptation ever. Maybe not the women (those characters need some major work to bring them into the twenty-first century), but the racism – while not excusable – is certainly reparable without much effort at all.

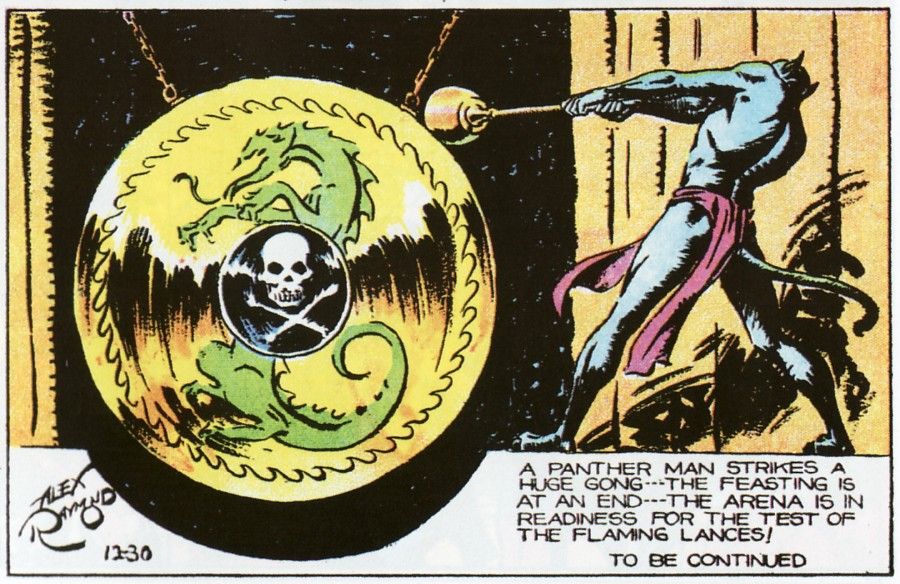

From the science to the stereotypes, Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon is a product of its time. But without overlooking those things, it would be a huge disservice to focus entirely on them (as I’ve pretty much done here, unfortunately) to the exclusion of the vast majority of fun, action-packed, exquisitely illustrated adventure that dominates the book. It really is hard to see why no one’s made a better movie from it.

Four out of five pirate-dragon gongs.