In this column, Mark Ginocchio (from Chasing Amazing) takes a look at the gimmick covers from the 1990s and gives his take on whether the comic in question was just a gimmick or whether the comic within the gimmick cover was good. Hence "Gimmick or Good?" Here is an archive of all the comics featured so far. We continue with 1991's glow in the dark cover for Sandman Special #1...

Sandman Special #1 (published March 1991) – written by Neil Gaiman, with art by Bryan Talbot and Mark Buckingham. Painted cover by Dave McKean

In a break of tradition here at Gimmick or Good, I’m taking a step away from superhero books for a week and instead focusing on a single issue from one of the most critically acclaimed comic book series of all time. Gaiman’s Sandman is one of those series that transcends the comic book medium. I like to tell people it’s the one comic book that my wife enjoys more than I do (I grew up with a healthy diet of caped and masked crusaders, so I almost always gravitate back toward those stories). In 1991, in the midst of the “Seasons of Mists” arc (Sandman #22-28), DC/Vertigo published Sandman Special #1, an all-new story that was actually an adaptation of the classic tale of Orpheus. The comic was one of the first in the industry history to utilize a “glow-in-the-dark” effect on the cover. In this case, once the lights were out, Orpheus’ face was revealed, along with a message from him, “In Dreams I Walk With U.”

But what about inside the comic?

Before I go any further, let me preface this entire spiel by saying I did not pick this issue so I could deliver the next in a long line of love letters to Gaiman and Sandman. I totally understand how beloved this series is by so many people – even people who don’t read comic books like my wife – but I’m not some kind of Sandman super fan about to sell you on something you’ve probably already been sold on for the past 20+ years. Yes, I LIKE Sandman but, like anything else in the world, sometimes a person forms an opinion about something based solely on personal taste. Some like Samoa cookies, and others love Tagalongs (sorry, I just got a few boxes of Girl Scouts cookies, so they must be on my mind). For me, Gaiman’s use of language and his rotating cast of guest artists are generally top shelf, but the overall story can, in some instances, just be a little too Gothic and pensive for my tastes. So, trust me when I say that whatever I decide here is not because I wanted to spend a week writing, “I love Sandman, I love Sandman, I love Sandman.”

Sandman Special #1 is an interesting entry because it’s a visual adaptation of one of history’s oldest stories – the tale of Orpheus, the musician and poet whose wife Eurydice dies on their wedding day after being bitten by an asp. Orpheus’ tale is so tragic that when he bargains for his love’s life back from the Underworld, Hades and Persephone are uncharacteristically moved and relent with a condition: Orpheus, in a game of trust, must walk in front of her and not look back until both reach the upper world. However, as Orpheus is merely steps away from his destination, he believes he’s been tricked by the rulers of the underworld and he looks back, only to see Eurydice pulled away from him again.

Since Sandman Special #1 is an adaptation, it really wouldn’t be appropriate for me to judge the comic’s actual story so, instead, I will focus on how Gaiman crafts it and works it into the world of Dream, Death and the rest of the Endless cast of characters, and how Talbot and Buckingham bring visual life to this tale through their artwork.

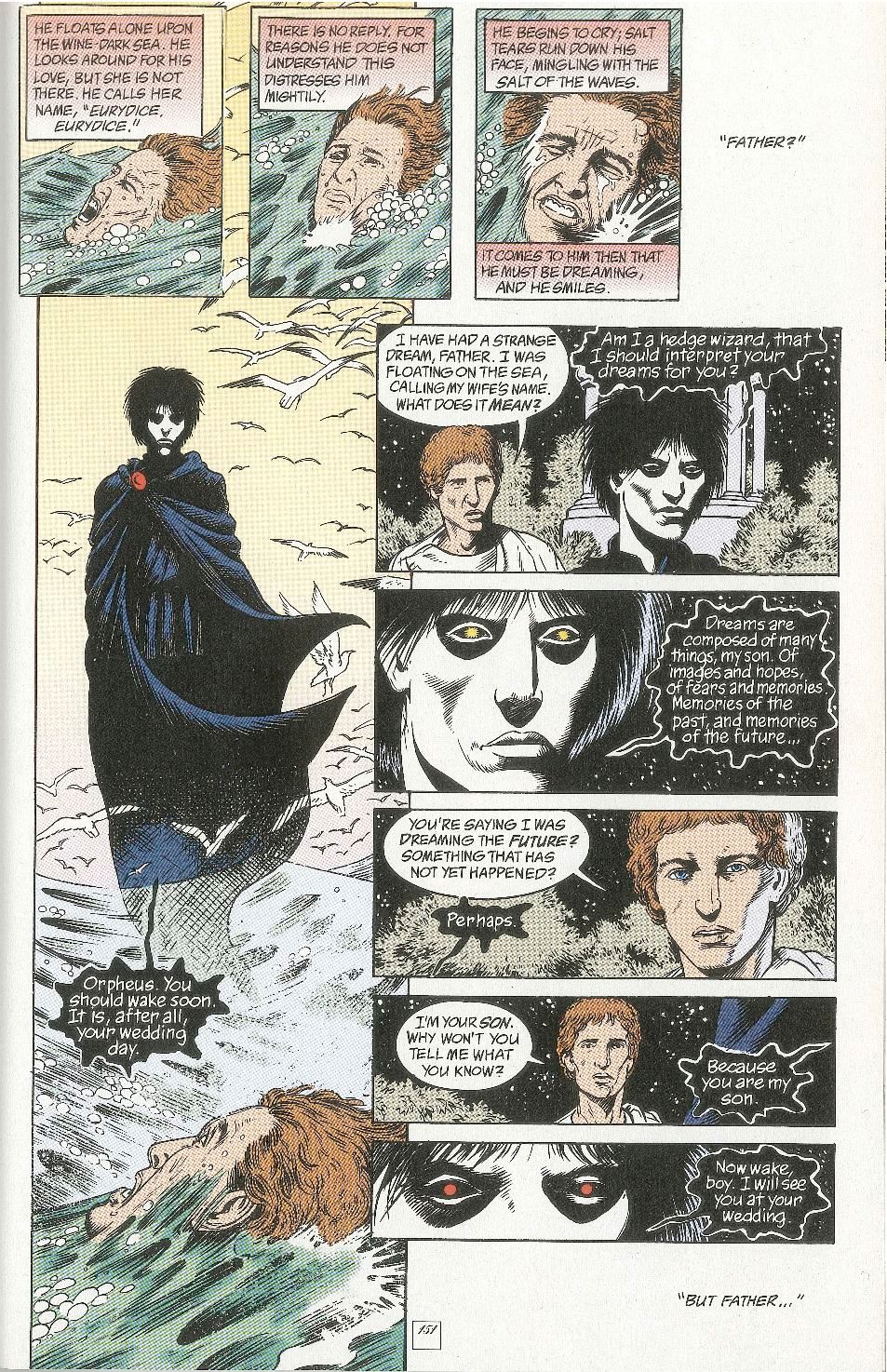

One of Gaiman’s first big decisions is making Orpheus the son of Dream, the protagonist of the Sandman series. This becomes essential when the story opens with what turns out to be a premonition of the ending – Orpheus’ head, floating out in the sea, calling out the name of his lover Eurydice. When Orpheus asks his father what the dream could be about, Dream dismisses the questions, telling his son he needs to get ready for his wedding day. This exchange establishes one of the prominent themes of both this issue and the entire Sandman series – the idea of destiny and its inability to be changed by the mortals who coexist and interact with the Endless.

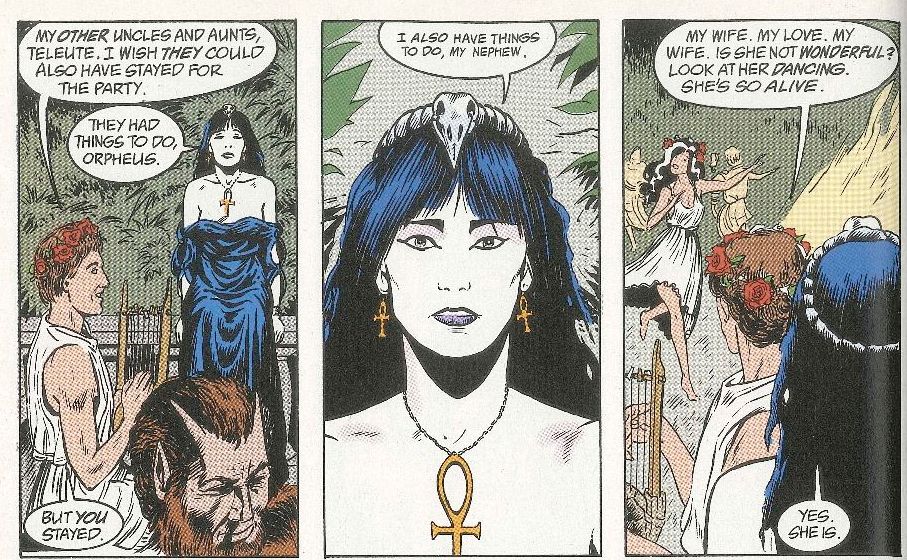

As is often the cases throughout the Sandman series, Death, here dubbed Telute, steals the comic from the rest of the cast. Gaiman’s Death is one of the fictional universe’s greatest ironies – to have such a feminine and joyful character embody the Grim Reaper. One of the most emotionally powerful panels in Sandman Special #1 illustrates a striking moment on Death’s face that is just ambiguous enough that it is open to interpretation. As the rest of Morpheus’ aunts and uncles shuttle off after his wedding ceremony, Orpheus asks Telute why she’s still around and she responds, “I also have things to do, my nephew.”

Death’s facial expression can best be described as vacant, but based on Gaiman’s set-up and payoff with Eurydice’s death, it conveys so much hidden emotion. As a reader, the expression’s overall simplicity makes me want to crawl inside her head and listen to her inner monologue. Does she feel sorrow? Regret? Obligation? Nothing? Gaiman, like the rest of the Endless, just doesn’t let us mere mortals know because, ultimately, what Death is thinking in that moment is irrelevant. All that is relevant is that she is there to see Eurydice off to the Underworld.

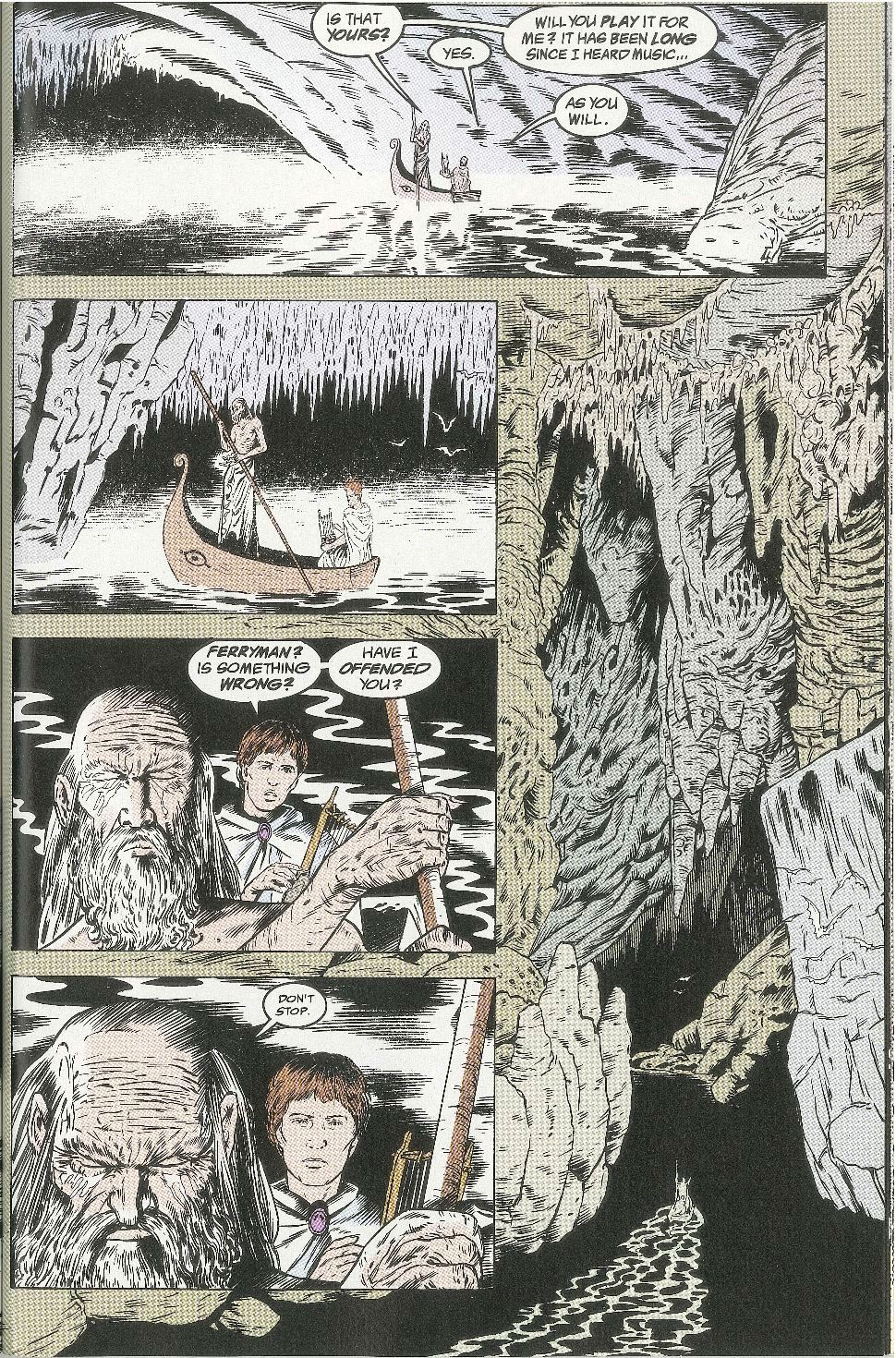

I love Talbot and Buckingham’s color palate in the Underworld sequences. Rather than saturate the pages with the colors of fire and brimstone, they use delicately light shades of blue, yellow and red. Orpheus is at first featured mostly in shadow, but as he starts to play his lyre – the music that eventually allows the inhabitants of the Underworld to sympathize with his sorrow – different colors begin to pop with more saturation.

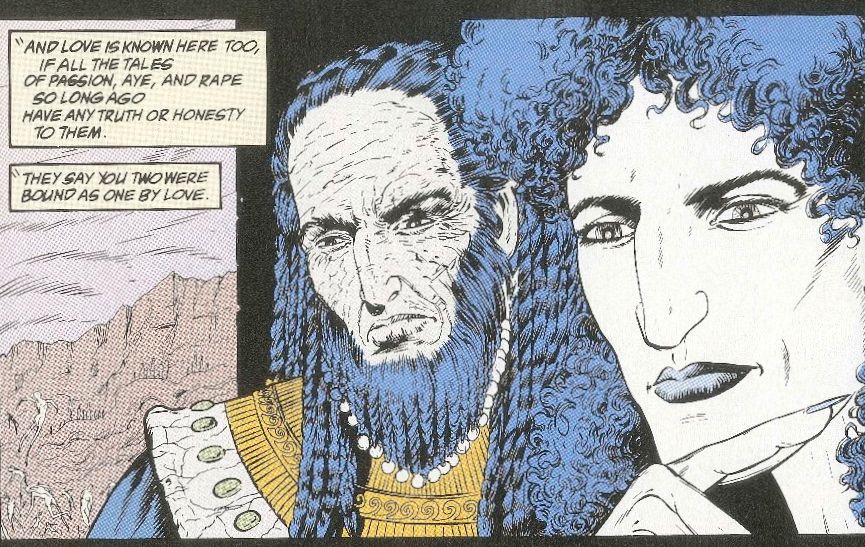

Hades and Persephone are drawn and inked with vivid detail – especially their hair. The art throughout the Sandman series has always been a tour de force, but I can’t stop appreciating the consistency of quality, even in the case of a one-shot like Sandman Special.

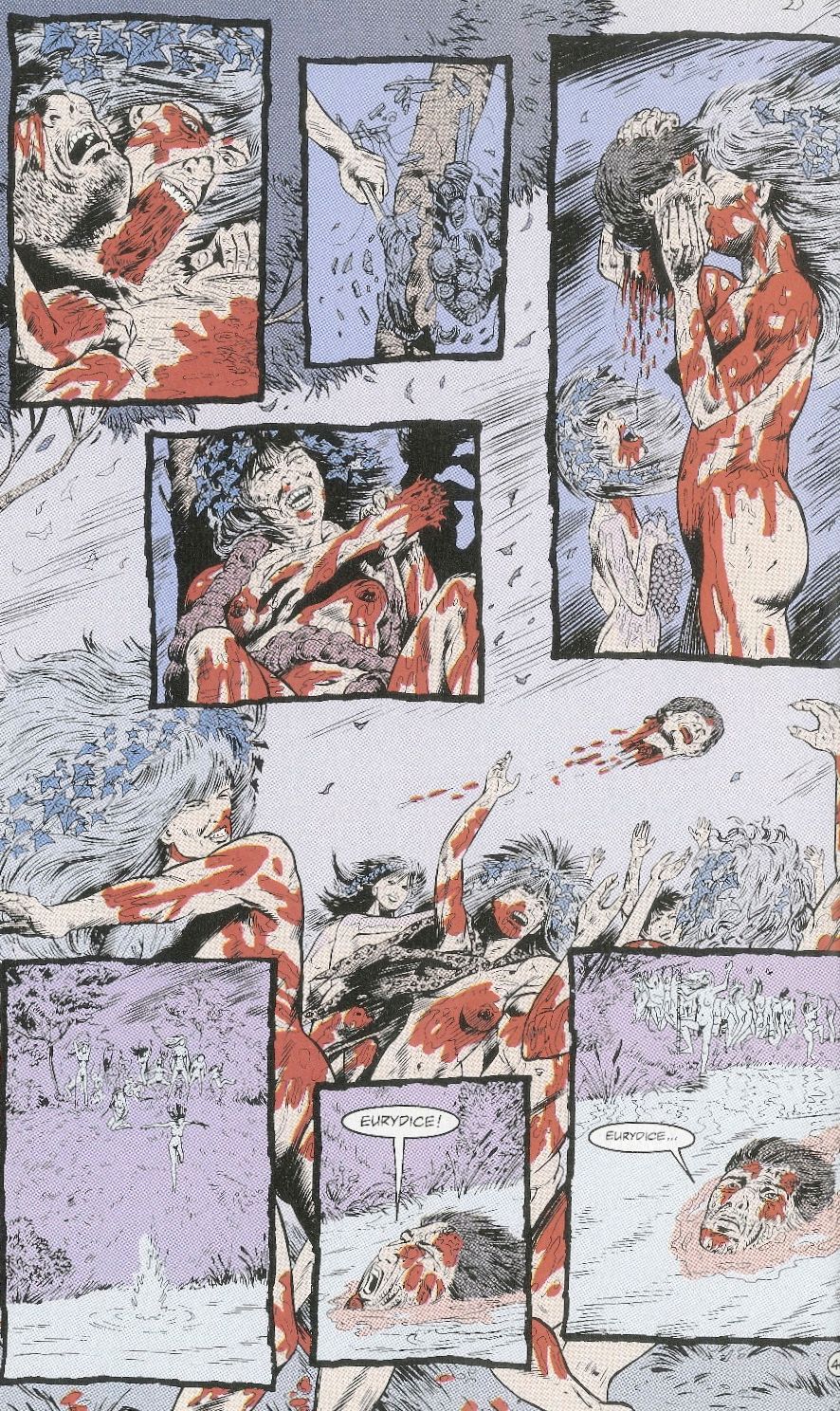

The one scene where I have some quibbles with this comic comes after Orpheus returns from the Underworld and has basically lost the will to live. His mother wants him to move on from his current physical position because a Bacchanal is set to come through, and he instead opts to stay put and allow himself to be devoured (and thus leaving only his head, which ties back to the story’s first panel).

Talbot and Buckingham return to the Underworld color palate, but with streaks of saturated red to simulate Orpheus’ blood. While I understand the imagery is by design, supposed to be unnerving for the reader, it still comes across as a bit too gore-for-the-sake-of-gore given how delicately illustrated the comic is leading to this moment. Maybe I’m just being squeamish, and I totally understand how my distaste for it can be interpreted as a moment of artistic brilliance for someone else, but this is an example of the Samoa versus Tagalong argument for me again.

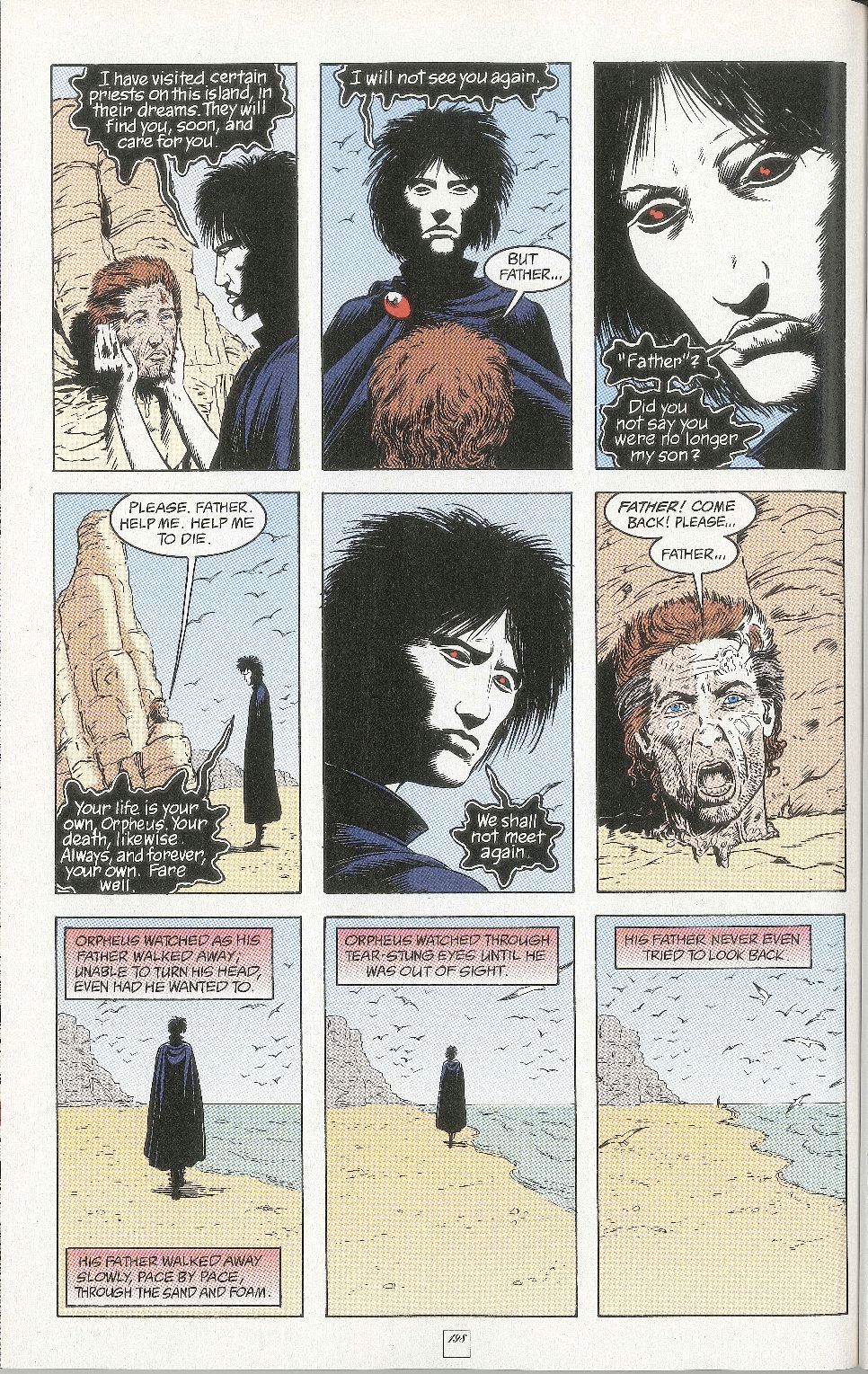

We end the story with yet another gut-punch moment in a comic. After disowning himself from his father, Orpheus’ remaining head calls out in agony and desperation to Dream. Dream says he’s surprised his son is calling him father again. He tells him this is the last time he will see him and that his “life and death” are “his own,” walking away from his son, never once turning back to look at him.

It’s another wonderfully ambiguous moment courtesy of Gaiman and the artistic team. One could say Dream is stubborn and despite Orpheus’ pain, he has not forgiven him for not listening to when he was warned about going to the Underworld to try and win back Eurydice. And yet, Gaiman also establishes earlier in the story that Dream does have love for his family, even if he has a funny way of showing it. Perhaps he’s just walking away from Orpheus with the words “father” still in his head, never bothering to look back in case that last moment of connection between father and son was just some kind of trick from the Underworld. Or perhaps, like the scene with Death at the wedding, what Dream is thinking is irrelevant because Orpheus’ “life and death” are “his own,” and thus, there’s no changing destiny.

Verdict: Good