In this column, Mark Ginocchio (from Chasing Amazing) takes a look at the gimmick covers from the 1990s and gives his take on whether the comic in question was just a gimmick or whether the comic within the gimmick cover was good. Hence "Gimmick or Good?" Here is an archive of all the comics featured so far. We continue with 1994's acetate plastic covered Marvels #1-4...

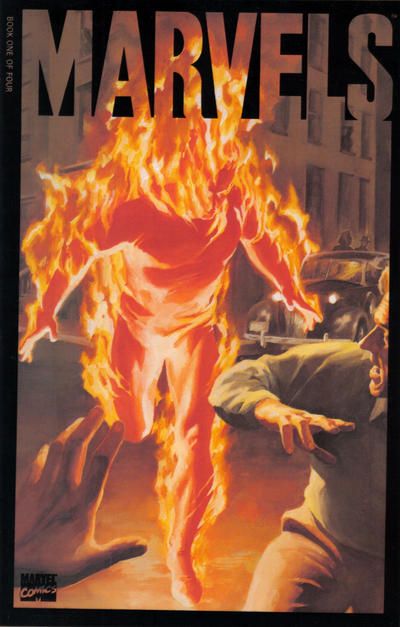

Marvels #1-4 (published January 1994-April 1994) script by Kurt Busiek, art by Alex Ross

This mid-90s Eisner-award winning mini-series re-imagines some of the greatest Golden and Silver Age stories in Marvel comics history like the birth of the Human Torch and Sub-Mariner in pre-World War II America, and the death of Gwen Stacy in 1972, through the lens of fictional photographer Phil Sheldon. The series is also famous for introducing artist Alex Ross and his painted covers and interiors to the mainstream comics consuming public. Still, rather than just letting the classic stories and wholly unique artwork speak for themselves, Marvel packaged each of the comics like commemorative books of artwork – complete with “protective” acetate plastic covers (which actually scratch more easily than standard covers) and a hefty (for the time) price tag of $4.95/$5.95 an issue.

But what about inside the comic?

Despite the gimmickry of the series’ packaging, Marvels was critically acclaimed upon its release and remains a classic and joy to read nearly 20 years later. It’s a prime example that not every comic book that received the hard sell “instant collectible” moniker during the comic book speculation boom of the 1990s was an illiterate waste of paper of acetate.

By telling these stories from the perspectives of average citizens, Busiek successfully recycles what was already celebrated content and provides better context as to how the superpowered heroes that first debuted when America was on the cusp of the “second great war” tied-in to the collective consciousness of a country undergoing seismic social change. This is especially true during the second, third and fourth issues of Marvels when the story focuses primarily on the rise of the X-Men, the Fantastic Four’s confrontation with the planet-consuming Galactus, and the death of the “innocent” Gwen Stacy.

It’s long been believed that Stan Lee’s original premise for the Uncanny X-Men was a superpowered look at racial tensions during the civil rights-era. Some have gone as far as to analyze that Professor X’s peaceful approach to human-mutant relations was reminiscent of Martin Luther King Jr., while Magneto’s “home superior” aggression reflected Malcom X. In Marvels #2, Sheldon, who after initially being afraid by the rise of the “Marvels” as he dubs the cast of heroes and villains, has come to embrace them, still finds himself participating in what resembles a lynch mob when it comes to the mutants. After throwing a rock at Iceman, he is stunned by the dismissive attitude of Cyclops, who tells his partner not to retaliate because the humans are “not worth it.” Then when Sheldon finds his young daughters hiding a mutant child in the house, the protagonist looks into the little girl’s eyes and sees parallels between her fear and exhaustion and what the liberators found in the survivors at Auschwitz during World War II. The experience makes Sheldon recognize his prejudice. Eventually, most people see Sheldon’s perspective when the Sentinels are introduced and start hunting and killing mutants without conscious.

The historic parallels continue to hold serve in Marvels #3 during the re-telling of the Galactus story. Galactus’ straightforward declaration to end all existence on Earth mirrors the looming threat of terror and nuclear holocaust during the Cold War between the United States and the U.S.S.R. Sheldon and his contemporaries are completely resigned to their inevitable mass demise.

In what may be one of the most brilliant use of visuals and (lack of) text in the entire series, Busiek and Ross intersperse Sheldon’s perspective with wordless splash pages of the Fantastic Four, the Silver Surfer and Galactus. Not only are the visuals stunning, but the lack of text really hammers home just how ultimately powerless the human race is against this threat. Just as was the case during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the game to stave off the apocalypse was negotiated at a much higher level than Phil and his contemporaries.

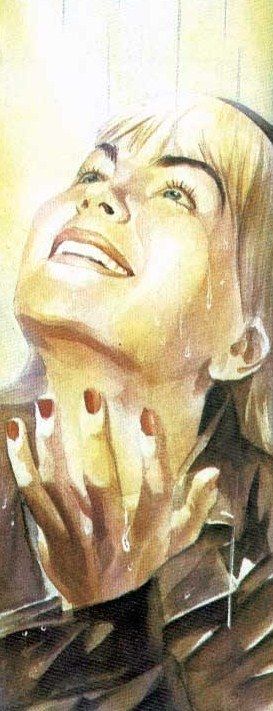

The series ends appropriately enough with Sheldon’s view on the “Death of Gwen Stacy,” which is popularly known as the official “end” of the Silver Age of comics in favor of darker, grittier stories. Busiek really plays up how Gwen’s death marks the end of innocence in the comic book universe and in the world of Sheldon’s Marvels. Sheldon initially meets with Gwen in an attempt to write a story that will clear Spider-Man’s name in the death of her father police Captain George Stacy. During their first encounter, Sheldon and Gwen are walking the New York City streets when Namor stages a non-violent protest. While everyone else is initially startled, Gwen looks up at Namor’s accompanying raindrops and in an almost angelic pose, absorbs the simple beauty of the moment. Gwen’s good nature makes her inevitable death at the hands of the Green Goblin (and the way it is ignored by the press in favor of the more “powerful” Norman Osborn’s death) all the more heartbreaking for Sheldon, who then retires from the game of documenting Marvels.

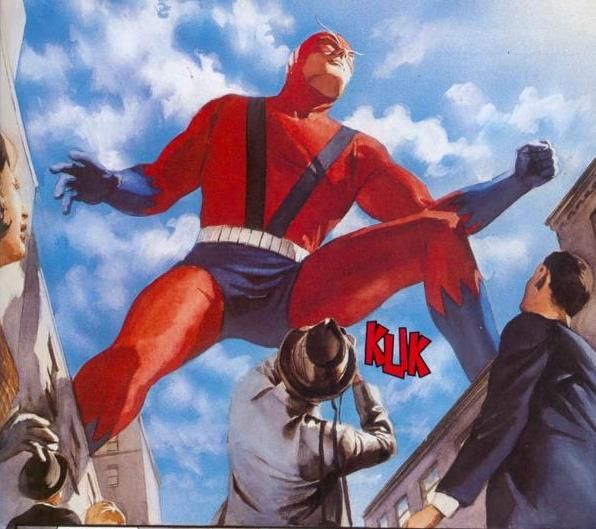

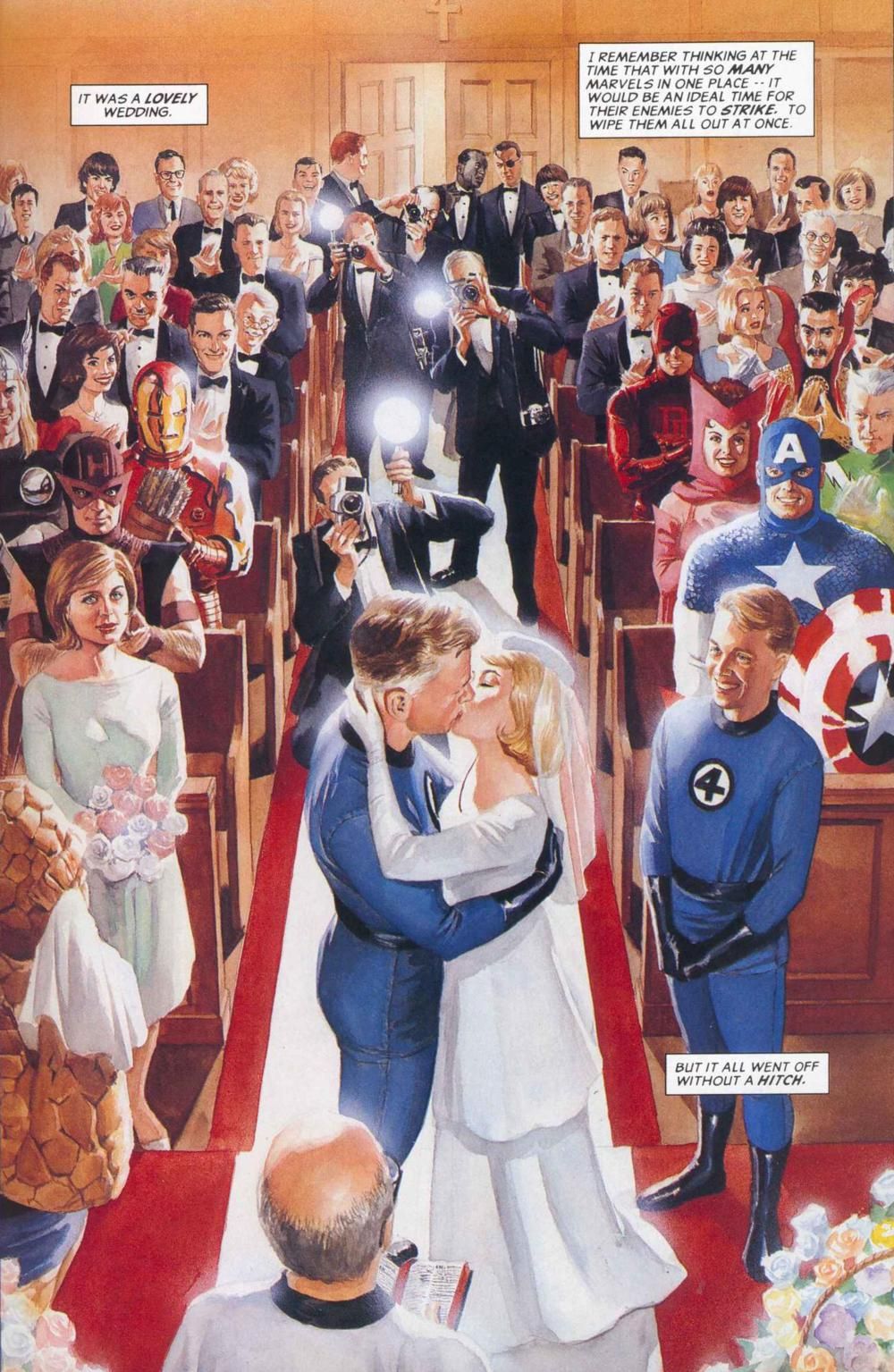

Beyond the intelligence of the story, Ross’ artwork includes some of the greatest visuals the comic book medium has ever featured. There are countless iconic panels beyond just the four covers (a low-angle Giant Man stepping across the city, Reed Richards and Sue Storm’s wedding kiss – complete with John Lennon and Dick Van Dyke in attendance), and the painted style just makes every visual come across as painstaking and meticulous.

While Ross would go on to recreate this style for countless other miniseries and variant covers, his work on Marvels remains my favorite.

My “gimmick or good” conclusion shouldn’t really be in doubt considering Marvels did win a couple of Eisner awards, but I always do like to point out to people who claim that today’s variant cover/special edition issue trends don’t match-up with the 1990s because today’s comics are “better,” that Marvels does exist and was released during the same period where publishers were placing holograms and polybags on anything they thought could generate buzz. And interestingly enough, despite its legacy and marketing, the series never became much of a collectible since you can find most copies of Marvels selling for LESS than what a person paid at their local comic book shop in 1994. However, anyone who’s turned off enough by the acetate covers and “book” packaging to not read this series is seriously missing out on one of the greatest series of the era.

Verdict: Good