Don't get us wrong. We here at CBR know the 1990s brought some amazing comics, including Todd McFarlane's Spawn, Frank Miller's Sin City, and more. Yet, on the whole, the decade really sucked for comic books. They don't call the 1990s the Dark Age of Comics because they stopped making comics; just the opposite. With a more mature feel brought on from the 1980s, more direct market comic shops to sell comics and comic books starting to become more popular, there were more and better comics than ever before.

RELATED: All-Time Worst Comic Book Gimmick Covers

Yet with that new freedom came a glut like the industry had never seen. Both the tone and the style of comics changed significantly, and not always for the better. Independent comics broke all the rules, which was exciting at first but got old fast, and comic books were treated more like collectables than books to read. It's time CBR explained why the Dark Age was so dark. A lot of the trends we'll talk about in this article are still going on, but there's no doubt that they were at their worst in the 1990s. Here are 15 reasons it was hard to be a comic book reader in the 1990s.

15 MULLETS

Let's start with one of the most trivial but also annoying trends of the 1990s, and that was the mullet. In the Golden Age, superheroes all had pretty much the same helmet hair, which was fine, because everyone else did too. The only ones allowed to have modern kinds of hair were the supervillains, because that's how you knew they were bad guys. In the 1960s and 1970s, things started to change with curly and longer hair. Superheroes actually started to look like real people with real hair.

Then came the 1990s, and mullets took over comic books. Peter Parker got a mullet. Tony Stark had a mullet. Thor grew a mullet. Even Superman had a mullet. It's like all the superheroes started going to the same barber, and they all said, "Make it long in the back and short on the sides, because that's the new style at the Justice League."

14 EXTREME EVERYTHING

If there was one word more overused in the 1990s than "extreme," we don't know what it is. The great thing about the word "extreme" is that it implied something new and exciting without actually needing to fit any definition. That's why comic books jumped on the "extreme" bandwagon, too.

"Extreme" ended up taking over the comic industry. There was 1995's Justice League spin-off Extreme Justice by Dan Vado and Marc Campos, and a blood-exploding mutant actually named X-Treme (seen above) introduced in 1993's X-Force Annual #2 (Fabian Nicieza and Antonio Daniel). Rob Liefeld even founded Extreme Studios within Image in 1992. There were also a lot of extreme sports superheroes like Night Thrasher whose main crime-fighting tool was a skateboard. After a while, all the "extreme" was seen to be a little... extreme and died out, right when everyone else in marketing realized the word was getting overused, too.

13 DARKNESS

In 1986, Frank Miller and Alan Moore caused a revolution in the comic book industry with two major works. Miller's The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen (by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons) introduced darker and more mature themes than anyone had ever seen in comics before. They questioned everything about comic books including superhero origins, the nature of justice, and heroism. The books signaled a new age where comic books were a mature and even cool art form.

It's not that there's no room for darkness in comic books, but an overly dark, cynical tone started to appear even in comics like Superman, which had long been about the lighter side of comics. It started as a riff on the Silver Age, and was meant to be more adult and mature. Yet, in many ways, the dark tone became more immature and ugly than fun.

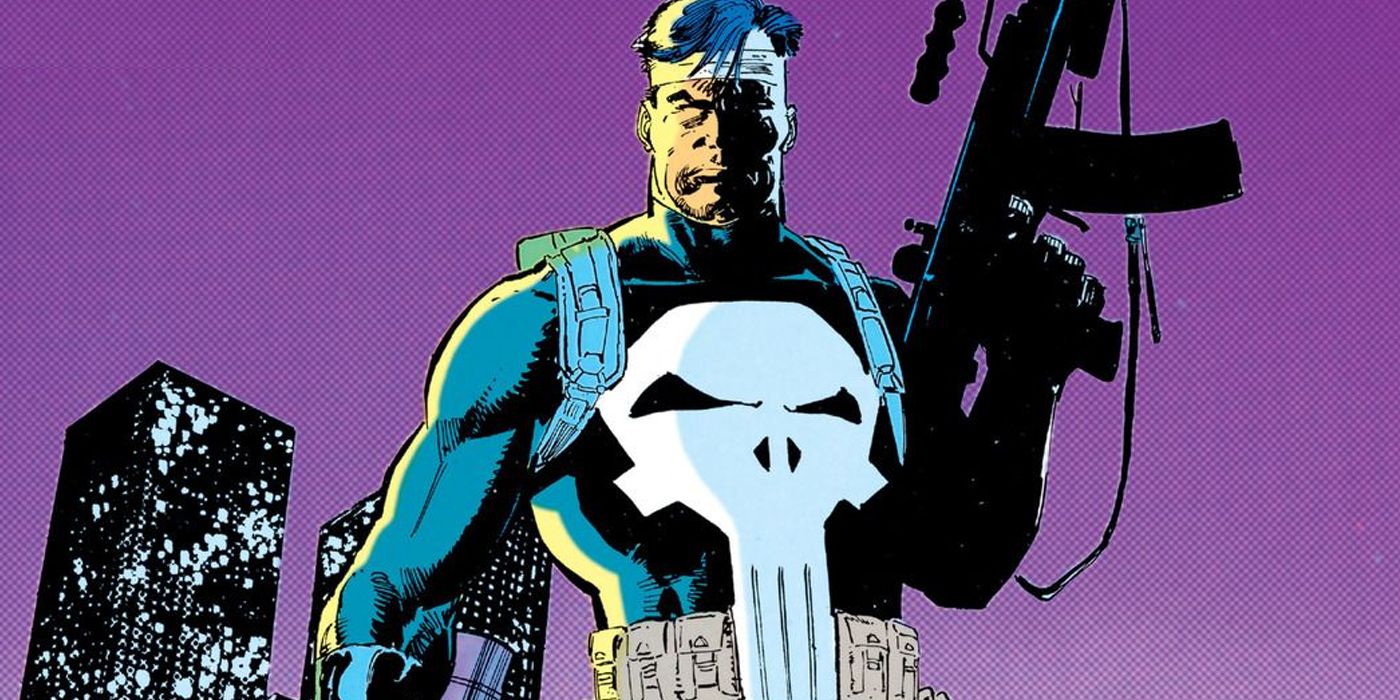

12 ANTIHEROES

Manifested in the 1980s, the loss of the Vietnam War led to bitterness about American heroes in general, which led to the rise of antiheroes. Superheroes like the Punisher and Wolverine fit the 1990s to a "T," and became major sellers. Other superheroes followed until regular heroes were in short supply.

There's room for antiheroes, but not every superhero can fit into the context of an antihero. Suddenly, it was hard to see where the line was between hero and villain. Alex Ross and Mark Waid's Kingdom Come in 1996 shone a light on the difference between the classic heroes of the past and the brutal heroes of the 1990s, where the violent heroes almost destroy the world, and only the old-school heroes can stop them. It came just in time to rethink the whole genre.

11 MURDER

In the Golden Age, superheroes like Batman would kill at the drop of a hat, but in the 1950s the Comics Code Authority frowned on heroes killing criminals. In the 1980s, as the CCA loosened up or was dropped altogether, comics reversed and went the opposite direction. The old ways of superheroes catching criminals and sending them to jail became a joke. In the 1990s, Professor X and Superman (two heroes who always went for peace if they could) were pushed to the background by Cable and Lobo (ironically, created to mock antiheroes).

Superheroes like 1992's Youngblood (Rob Liefeld, Dan Fraga) didn't even bother trying to arrest anyone. They'd bust in with a vengeance, killing everything in sight. It was frustrating to see superheroes racking up a larger body count than supervillains, and lacked any nuance in justice. It's a wonder anyone went to prison at all in the 1990s.

10 CYBORGS

Cyborgs have been a part of comic books for a very long time, but the 1990s really went into overdrive on the concept. Cyborgs exploded in movies like 1987's Robocop, and the comics followed suit. Cable was one of the most popular cyborgs in the 1990s, which revived superheroes like Deathlok (first appearing in 1974's Astonishing Tales #25 by Doug Moench and Rich Buckler) and led to a growth of supervillains like the X-Men's Reavers who were all cyborg-driven villains. In independent comics, a whole team called CyberForce was created in 1992 by Marc Silvestri. Even Superman became a cyborg after the "Death of Superman" event.

While there's nothing wrong with a few cyborgs, when whole teams of superheroes and supervillains were nothing but cyborgs, it got a little crazy. The lens flare from all that chrome on a single page could become blinding. Eventually, the cyborg craze died out, giving way to nanotechnology craze of today, but that's another story.

9 GRITTINESS

If there's one word that captured the 1990s, it might be "gritty." The clean streets of the Silver Age were replaced with trash and filth-covered streets. Clean-shaven heroes grew stubble, and smiling heroes switched to gritted teeth in every panel. While these were things that really made Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns stand out, they became overused in the 1990s.

The new generation of comics didn't have the subtlety or complexity of more mature works, just a lot of clenched jaws and squinting eyes. There's more to being "gritty" than having a lot of dots and lines. After a while, the grittiness began to seem more repetitive than mature, and comics moved on to have more of a balance.

8 GUNS

One of the other casualties of the Comics Code Authority had been the use of guns. It's not that guns weren't a part of comics, but the code tended to frown on extreme violence, so superheroes tended to fall back on energy beams. That all changed in the 1980s with the loosening of the Code when things went in the opposite direction. Suddenly, being able to shoot a gun was a superpower.

There were whole categories of superheroes like Grifter of 1992's WildC.A.T.S. (Jim Lee, Brandon Choi) or Deadpool (from 1991's New Mutants #98 by Rob Liefeld and Fabian Nicieza) whose main hook was a fondness for lots of guns. There wasn't anything necessarily wrong with gunplay, but comic book pages became filled with guns bigger than small children over anything else. After a while, readers craved actual superpowers again, and the guns became just a part of storytelling instead of the main hook.

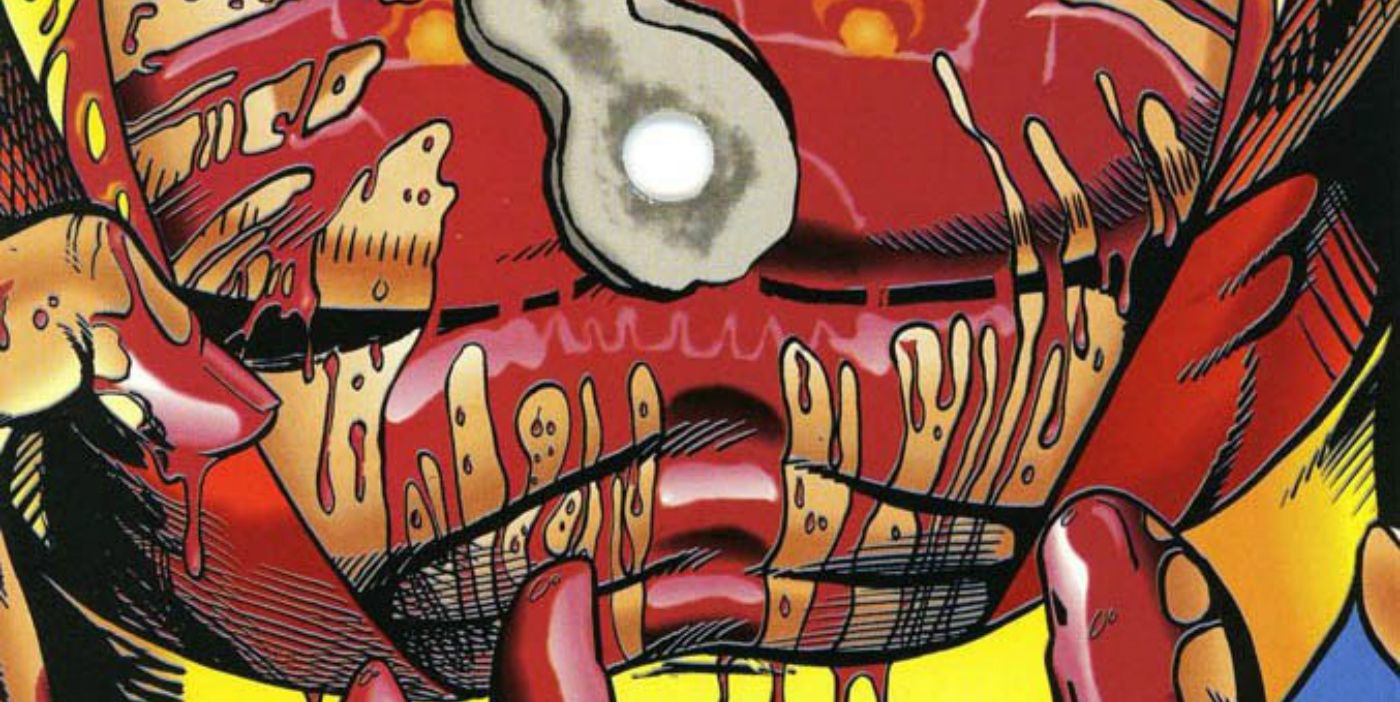

7 BLADES

As more comics opted out of the CCA, comic books began using more violence, enjoying their newfound freedom. After decades of restrictions on how much violence they could show on panel, artists and writers began filling the pages with gore. That's why blades got a lot of legwork in the 1990s.

Most of these superheroes were trying to copy the runaway success of Wolverine, who couldn't use his claws to their full potential because of Marvel's restrictions. Independent publishers were more than willing to fill the gap. A lot of new heroes also ended up with long knives and swords as part of their arsenal, because they gave an excuse for lots of guts on the pages. Eventually, after the shock value wore off, the use of gore in comics died down, and the fondness for swords and knives dropped, too.

6 BAD GIRLS

The 1990s also brought "bad girl" books about strong heroines who also happened to be easy on the eyes. Publishers got to claim they were about feminism and equality while also pandering to their young male audience. There had been "bad girl" characters before with 1969's Vampirella (Forrest J Ackerman, Trina Robbins) and Frank Miller and Bill Sienkiewicz's Elektra: Assassin in 1986, but never like this.

One of the first "bad girls" came in 1992 with Lady Death (Brian Pulido, Steven Hughes). More followed, including Witchblade (Marc Silvestri, David Wohl, Brian Haberlin, Michael Turner) in 1995. Most of them had skimpy outfits, supernatural elements and a love of killing their enemies, and were more about cheesecake than actual stories. Eventually, a decline in the speculator market led to a drop in bad girls, but more realistic heroines have taken their place, which is a good thing.

5 ZOMBIES

We know what you're thinking. Zombies are a modern craze, still overused in comics. Well, in the 1990s, the zombies were the good guys. It seemed like being killed and brought back to life makes you more of a hero, not less. Comic books flooded with superheroes who could take a lot of punishment, because they were already dead.

1993's Bloodstrike was about a team of violent antiheroes who were brought back to life. Milestone had 1992's Xombi (by John Rozum and Denys Cowan) about another hero revived by nanotechnology. Even Todd McFarlane's Spawn in 1992 was technically an undead zombie. The main purpose of making your hero a zombie was to have them get gunned down, cut in half or blown up, and they continued to fight. It also fit the Rule of Cool.

4 COVER GIMMICKS

One of the movements that truly came into its own in the 1990s was the speculator market. The comic book industry went into a bubble as collectors grabbed as many copies of every comic they could find, hoping to find the next big hit. The comic companies were only too happy to make more comics, which led to cash grabs like the comic book cover variants. Some of them were good, but others went too far.

There were covers with four or five different colors, or slightly different art or covers made of metal and holofoil. Crazyman #1's cover in 1993 (Peter Stone, Neal Adams, Dan Barry) was cut in the shape of Crazyman's face. There were even comics with bloody holes punched into them all through the issue like Protectors #5 (R. A. Jones, Thomas Derenick). It was just a cash grab to get the reader to buy the same comic over and over again, which got burned out after the speculator bubble burst in 1996.

3 PUBLICITY STUNTS

Right along with the speculator market came publicity stunts, things comic book companies did just to try to drum up sales. At DC, Batman's back was broken in 1993's Knightfall saga and Superman was killed by Doomsday in 1992. Those were pretty good, but suddenly that wasn't enough.

Over at Marvel, Spider-Man went through the Clone Saga, trying to make it seem like he was a clone all along. Superman lost his old powers and gained electrical powers to become Superman Red and Blue. The beloved Green Lantern, Hal Jordan, became a supervillain. Aquaman had his hand chopped off and replaced with a hook. It got to the point where more people were being killed and resurrected than ever before. It also became less effective, making it harder to get attention in the process, which cheapened any real changes that came along.

2 LATENESS

With the rise of independent comics came a new type of comic creator. No longer tied to Marvel or DC, independent writers and artists were free to do whatever they wanted. They could be their own bosses and write about or draw anything without being limited by contracts or schedules.

Unfortunately, many creators found the worst kind of boss is yourself. Having to deal with all the boring parts of running a company, along with not having anyone holding them to a schedule or help with the workload, made producing monthly comics way harder. Comic books (particularly books from Image Comics) would end up running late by weeks or even months. This led to frustration among readers who would get all excited about a new comic, then get tired of waiting for the next issue. Some stopped reading the series altogether, which caused sales to plummet.

1 CROSSOVERS

No one here is saying that crossovers are a bad thing or that they started in the 1990s, because Secret Wars in 1984 and 1985's Crisis on Infinite Earths started the trend of major crossovers becoming yearly events. Unfortunately, the constant crossovers grew frustrating when the flow of stories in individual titles kept getting broken, and having to buy all the different books just to follow the story.

The absolute peak of the crossover craze came in 1993 when Image and Valiant decided to work together on a crossover event called Deathmate. An ambitious miniseries that used colors instead of numbers, meant to be read in any order, backfired so horribly that sales for both companies' regular titles plummeted, Valiant closed down, and some even blame Deathmate for the crash of 1996 that almost destroyed the comic industry.

What did you think of the 1990s in comics? Let us know in the comments!