The Power & Responsibility of Creator-Owned Comics

This is the two hundred and fiftieth "Tilting at Windmills!" Not that that means anything, per se, but we in comics always fetishize the quinquagenary anniversaries, so the big two-five-oh seems like it is worth a mention.

I sometimes joke privately that I almost certainly could probably take any number of columns I have written over the decades, change a few names, and run it again and no one would even know, but at the vantage of #250, I have to tell you that I think it is absolutely true that history repeats itself, over and over. At least in comics!

Part of that is human nature and human hubris, of course, but it is startling (if not a bit frustrating) to watch the same mistakes get endlessly made when the pitfalls are so well known.

The majority of dollars in this business are generated through serialization -- even if we look at BookScan you can see that the largest percentage of sales are generated from books that were serialized first. Probably at least $100 million of the $140m in 2016's sales was serialized before collection. Serialization is the major economic engine that drives the publication of comics in America and, therefore, production deadlines become the lash that propels that engine.

After all, you can't sell a comic that doesn't come out, can you?

Last month we talked a bit about licensed comics, and it seems we talk endlessly about the "mainstream" comics: corporate-owned superheroes, so this time let's talk a little about the complete reverse: Creator-Owned Comics.

It's really a little perverse to me that we have to differentiate, because one would think that creator-ownership is a universal goal of both creators and the market as a whole (on the theory that an involved and compensated creator is then deeply incentivized to create more and better work). But a whole lot of the output of comics industry is actually "Work For Hire," so "creator-ownership" is more of a movement than an assumption. At the end of the day, I've always liked 1988's Creator's Bill of Rights as a good working definition of How Things Should Be.

For me, it might largely be about rights reversion -- if, at the end of the contract to publish, all rights go back to the creators where they can freely shop the book around, then it's creator-owned. Of course, this would require the contract to have a stipulated time period, leaving things out like the alleged story with the original "Watchmen" contract that rights would have reverted to Gibbons and Moore, except that the contract only ended when "Watchmen" went "out of print," which it never did.

However, I also think that rights almost always imply responsibilities. Consider it the difference between renting and owning -- if something is not yours, you have no external incentive to worry about its condition or value, whereas if you own it, you have to worry about losing your investment.

Virtually all new original non-licensed graphic novels are probably being created under favorable creator-ownership terms, but like I said earlier, it's actually serialization that's the economic engine in comics. (And, frankly, I think that at least some of the bigger names in GN creation would ultimately sell significantly more copies if they serialized first, but that's an argument for a different column!) This means, if you want to have the largest possible success in comics you need to feed and care for your market.

We see it again and again, history repeating itself, a creator does steady clockwork production of work on the corporate-owned superhero or licensed comics, but when it comes down to their own work, they start to slack on the actual production. Stuff stops coming out on time, or comes in fits and starts, totally blowing the market for the work and frustrating the end consumer.

This isn't a matter of "George Martin is my Bitch," because we're talking about market functionality, not audience entitlement -- if you announce that you're doing a six-issue monthly comic, then you need to release six monthly issues, it's really just that simple. But no one says that you can only release comics monthly -- the market only needs what you tell it to expect. Comics can be released bi-monthly or quarterly or annually, comics can be released in arcs with gaps between to catch up on production, comics can be released on virtually any schedule or scheme you propose -- but once you commit to that plan it is absolutely essential you hew to it, and to clearly and loudly communicate any changes as far as possible in advance.

Scheduling can trip up seasoned professional after seasoned professional. I could make a list, but it would probably be at least a page long, full of big-name creators who reliably hit corporate deadlines for years. Now one imagines that part of the problem is no longer having the corporate machine behind you, pushing you forward. But if it is literally external traffic management that keeps you moving (and for many people that's probably a pretty reasonable assumption), then find or hire someone to do that work for you.

When you're working on a creator-owned comic, it's as much on you as any publisher that you work with to actually get the material on the stands, to act as a professional, to get the work done when you say it is going to be done. Because nothing kills the momentum of a book deader than lateness. Looking at a creator-owned-only company like Image, I get deeply frustrated when I see nearly two dozen outstanding comics solicited in the last year that still haven't shipped, and that haven't been cancelled. That's no way to sell comics.

Here's the thing (which we've talked about before): the only commodity that actually matters in the 21st Century is time/attention -- we live in a time of creative excess where Everything That Ever Was is Available Forever (not really, but it does seem like it) where there's far far more comics and "geek-related" TV and movies than one can reasonably hope to keep up on just the new stuff coming out, let alone all of the treasures of the past. This changes your relationship to the work itself, I think. And it also means, when coupled with the firehose of "content" gushing out, that the standards and patience and forbearance of the market grow increasingly strict as time goes on. It's also why circulations are dropping: there's only so much bandwidth of attention and rackspace and headspace available out there, and we've long since hit Peak Geek.

What this translates to is that your commercial value to the marketplace largely becomes a relationship of how you keep your promises to the market. And this is where we get back to the creator-owned/corporate split -- there are stores that are primarily corporate-comics-only because they feel "burned" by the actions of creator-owned books over the years. I mean, I know it sounds wacky, but I once met a retailer who told me that he didn't do anything except corporate superheroes and licensed comics because he was burned by Brian Michael Bendis' Icon comics.

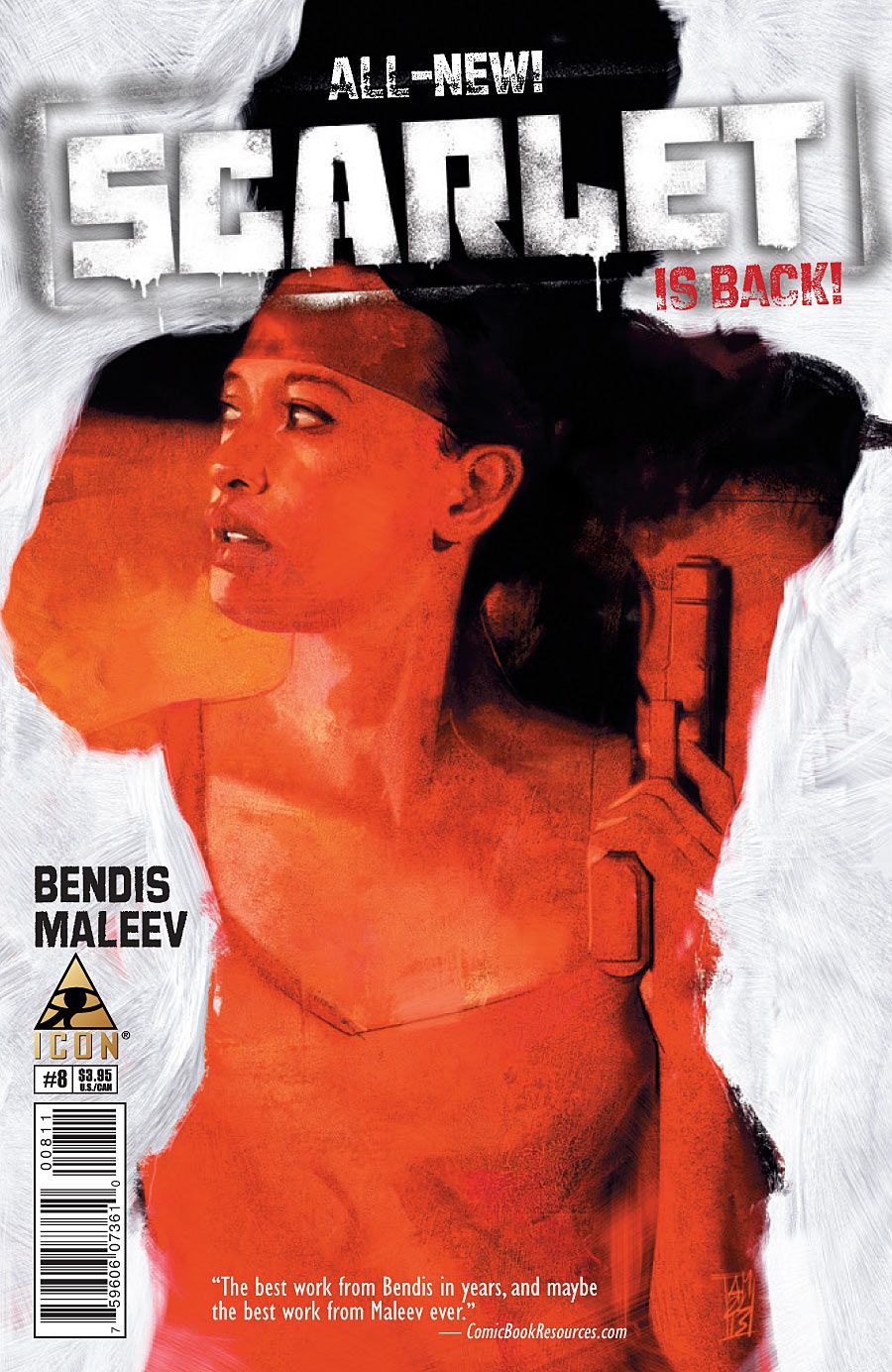

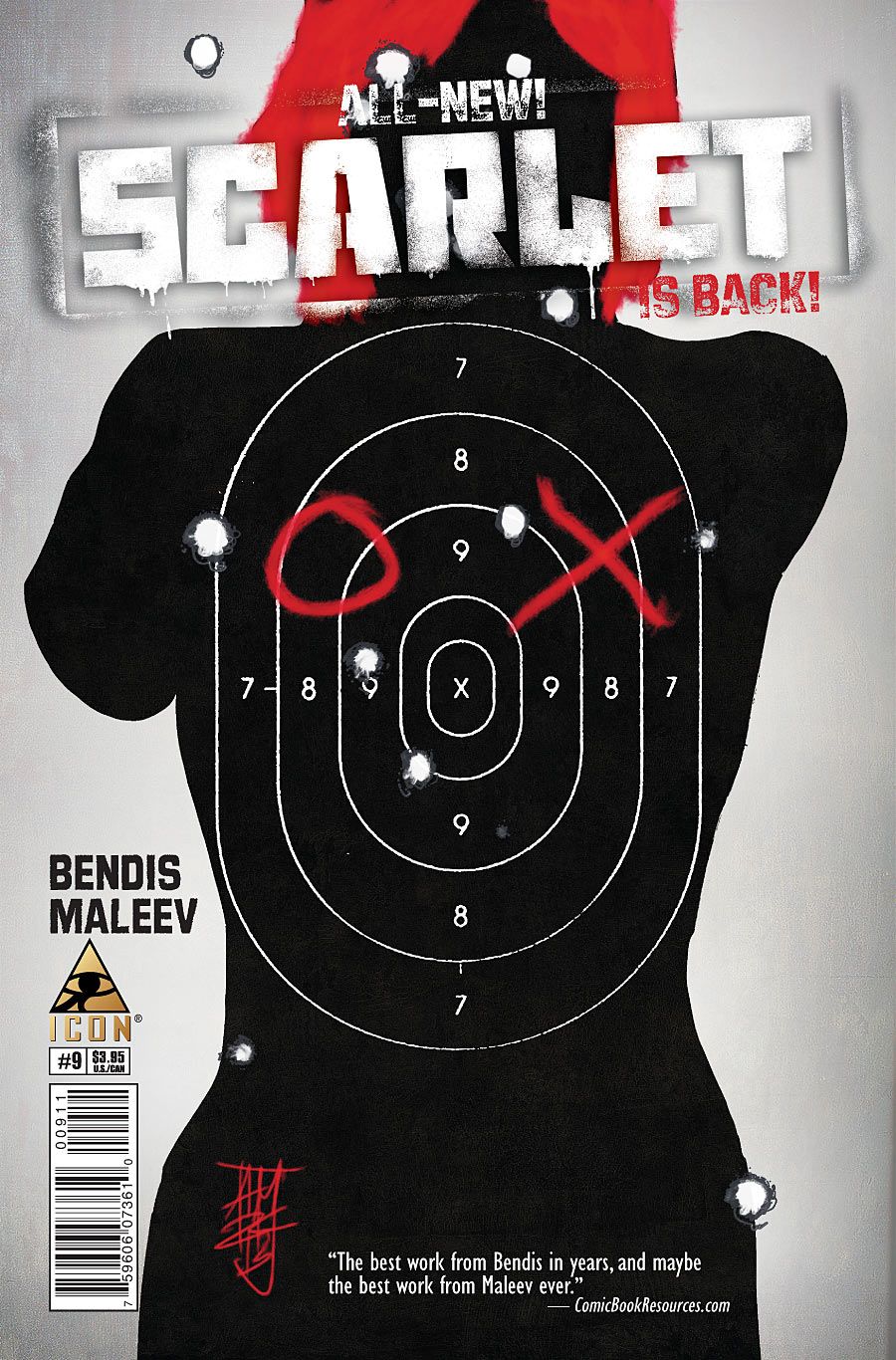

Not that that retailer, no matter how wacky, didn't kind of have a point of sorts -- Bendis just took his "Scarlet" off the market for three years, then shipped two issues within two weeks of one another. That's not anything but a "screw you" to the readership and the retailers buying non-returnable -- comics that are three years late have their commercial prospects annihilated, and then to shove two issues out in two weeks? What kind of a person does that? Bendis, in fact, is the one guy who drastically abuses Final Order Cutoff more than anyone else -- there are creator-owned comics of his that have been on FOC a dozen times or more before finally shipping (note the phrase "Final Order" in that construction?) propagating consumer confusion and poor data all along the chain.

I don't want to claim that publishing comics is easy or anything -- but the basic standard we should expect from anyone is to at least keep their word.

Convincing consumers to try new books is hard; hell, convincing retailers to give shelf space to untested ideas is much more difficult than you might imagine, so not doing the minimum expected job of publishing (i.e. actually publishing your comic) doesn't just harm you, it harms every other creator-owner out there by association.

Take responsibility.

Brian Hibbs has owned and operated Comix Experience in San Francisco since 1989, was a founding member of the Board of Directors of ComicsPRO, has sat on the Board of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, and has been an Eisner Award judge. Feel free to e-mail him with any comments. You can purchase two collections of the first Tilting at Windmills (originally serialized in Comics Retailer magazine) published by IDW Publishing, as well as find an archive of pre-CBR installments right here. Brian is also available to consult for your publishing or retailing program..