As Grant Morrison and J.G. Jones' "Final Crisis" comes just thirty-odd pages away from its middle point and reaches a self-imposed (and cleverly explained) thirty day hiatus, it's clear that while it features a universe-gripping threat and more heroes than you can count, it is extremely unconventional for an event comic, or even a superhero comic for that matter.

The pacing, in its consistency, has solidified itself as focusing rarely on the singular act of import -- Darkseid's transformation, Mary Marvel's possession and perversion in Granny's labs -- but instead on the events on the outskirts. Things are alluded to instead of directly illustrated, and actions are rarely as important as reactions. I am reminded of David Simon's crime drama "The Wire" in which as often as you'd see a sudden firefight or act of violence, you'd just as likely come up on a crime scene and a significant character revealed dead only then, with McNulty and Bunk lingering among the fallout.

"Final Crisis" is a lot like that. We're getting slivers of information among the collected moments that trace everywhere from Frankenstein versus The Question (truly the confrontation no one could have ever seen coming) to a recovering Jay Garrick in the West family living room. I couldn't help but notice that a very small moment in #1 telegraphed this entire approach. In the first sequence when Vandal Savage is tearing through a camp of cro-magnons, he spies the nubile daughter of the tribe leader. She is brandishing an axe. In the very next panel, Vandal is dragging her out of the tent, the axe buried in his shoulder. Pretty much every significant event in "Final Crisis" is handled like the swing of that axe. We see the before, we see the after, and it's up to us to fill in the rest.

I can see how this can chafe. A common complaint about the book is that nothing happens. Of course this couldn't be farther from the truth. Lois Lane is on Death's door. Gods have been murdered. A Flash has been resurrected. Hal Jordan is in custody. Batman is captured. Turpin is subsumed by the ultimate evil. But more often than not, we're not shown these things. We just know they happened.

So why exactly is Morrison staging "Final Crisis" like this? Why gather up a brand new All Star Squadron if only to show them in a splash page standing around looking worried? Where's my 100 v. 100 massive battle spread?

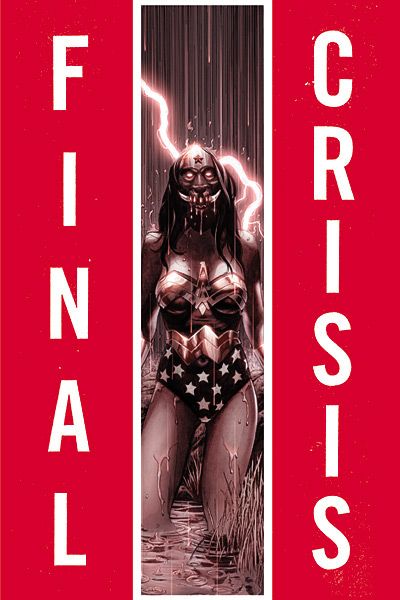

One need only look to the biggest fight in this book, Wonder Woman versus Mary Marvel, for your answer. Instead of an abstract beat-em-up sequence made up more of impact bursts than actual fighting, we have an unmistakably brutal sequence of hand to hand combat; Teeth are knocked out, arms are broken. You can't multiply that across the hundreds of combatants Alan Scott lets loose in this story and retain the same impact.

That critical sense of realism is naturally enhanced by the artwork of J.G. Jones, who turns in his most consistently great work of the series so far in this issue. The seams of the costumes, the grit surrounding open wounds, the shrapnel flinging away from sudden explosions; they all contribute to the sense of an all-too tangible impact of an increasingly horrible and perverted evil.

A lot of the more interesting moments of "52" and "Infinite Crisis" were when someone like Crispus Allen was on the ground level, staring up at the impossible. In "Final Crisis", Morrison has done this to the entire DC Universe. Even the strongest heroes among them have been rendered inert, trapped on the ground level of their own staggering event book.

They're not superheroes anymore, not in any way that can really make a difference. They're powerless. If a more dire and impossible threat has even been laid at a superhero universe's feet with such implacable verve and detail, I have to admit, I've never seen it.