With "Ex Machina," first-time director Alex Garland presents a highly relatable storyline centered around issues of artificial intelligence that appear to become more relevant with each new technological step forward. Exceptionally well-acted and sumptuously photographed, the movie has been hailed by critics as one of the best pure science fiction films in recent memory, and Garland has emerged as one of the most intriguing and promising filmmakers of his generation, genre and otherwise.

Review: A Modern Masterpiece, ‘Ex Machina’ is a Must-See Film

Garland's first novel was "The Beach," which brought him into partnership with filmmaker Danny Boyle when Boyle adapted the book into the Leonardo DiCaprio-starring feature. The two subsequently collaborated when Boyle tapped Garland to pen the screenplays for the smartly re-conceived zombie thriller "28 Days Later" and the acclaimed psychological outer space drama "Sunshine." Garland then adapted Kazuo Ishiguro's cloning-themed novel "Never Let Me Go" for the screen, followed by writing and producing 2012's well-regarded "Dredd," an adaptation of the British comic book "Judge Dredd."

Proving as assured a storyteller in the director's chair as he had on the page, Garland -- who collaborated with comic book artist Jock on the film's visual elements -- sat down with Spinoff Online for a revealing conversation about how the all the various mechanics of "Ex Machina" came together with such precision.

Spinoff Online: What was the itch in the back of your brain that started this story for you, that got you building this out into an actual story?

Alex Garland: There's a three step process that probably began when I was -- and I'm slightly guessing here -- but I would probably say around 12, something like that. I don't have any facility for coding, but I'm 44, born in 1970: my life has kept track with video games and home computers, basically. When I was about 12, it was this period of time when parents felt it was almost like an obligation to try and get a home computer for their kid, because of the way the world was moving, I guess. So there was a British computer, ZX Spectrum. It had on its keyboard Basic commands, as in the language Basic, and I started writing ultra-limited, very banal programs, which would be things like text adventures where you could say "You could go north, south, east, west," and you would program it in.

But also little conversations. And the one, it would go along the lines of the computer would say -- they're like "Hello, World" programs -- "Hello, how are you?" "I'm fine, how are you?" "I'm good." So on. Now that, it just simply made an impact on me and it never left me, which was the weird sense that the machine might be alive. You knew it wasn't alive, but it had the kind of electricity of feeling like it might be. Particularly in the sort of child's imagination, I guess. And that never, ever left me.

Years later, a friend of mine who is really big into neuroscience, that's his thing, and belongs to a school of thought that says computers can never be sentient, for various reasons -- there's a very strong argument, there's lots of big sort of thinkers and heavyweights who concur -- and he belongs to that school of thought. He would explain it to me and talk through it, and always I used to feel, "I just don't buy this. It doesn't feel right." So, he'd talk about things like Qualia, that sort of philosophical conceits. I'd read up about them, and the more I read, the more interested I got. But still, it was always taking me away from his position, not towards it.

And then the final part of that process is, I'm out in South Africa doing prep on this movie, "Dredd," which we're going to shoot imminently. I've got this book, which is kind of keeping me sane at that time, and it's about the relationship between the consciousness and embodiment, and it's written by the Professor of Cognitive Robotics at Imperial, which is our version of MIT. It's a very difficult book for me to read. I can't read all of it, but I can read some of it. And while I'm reading, I'm thinking, "This is the most interesting thing I've ever read in my life." Trying to hold onto it in my head. And just like a sort of pop, this idea emerges. I write it down really quick and then park it for year and half, or two years, I can't remember. Pretty close to the point of handing over "Dredd" -- I sort of dug it up and got working.

I feel like we've entered an era of pretty smart science fiction, where the timing is right for people to tell stories like the one you've told. The technology is making it easier for you to give your story a fantastic element on a reasonable budget. Tell me how you feel about what's happening in science fiction and cinematic storytelling right now.

I think that what's happened -- this is just a personal perspective -- I don't see it to do with sci-fi. I think sci-fi would be part of it. I'm a big sci-fi fan. But for me, it's actually about American television. American television has completely rewritten the rulebook of what film drama is allowed to contain. And the rulebook it's rewritten used to exist. In the '70s, it was just there. So I can feel a connection -- it's an apparent connection -- between Taxi Driver and Breaking Bad. These are adult dramas with, in a way, quite similar sets of concerns.

I think that film -- by which I mean cinema -- has been taught a lesson, really, by American TV. I'm being specific about American TV, because it is really American TV, and the lesson is, "Raise your fucking game." That's the message that I get, is, "Raise your game." I'm not saying it's all film. There's always been people doing great stuff -- Soderbergh and the Coen brothers -- and they've always been keeping this alive, this adult drama. But there've been significant pressures, powerful pressures, that have been an obstacle. It depends where you want to say it changed, but to my mind, in my consciousness, my awareness, it was "The Sopranos" and suddenly everyone just woke up, like, "Wow. Look what you can do with a film narrative, and people will come."

Tell me about setting a story that has a future-thinking -- probably not too far off in the future -- concept, but also keeping it very human, keeping it very relatable. Telling these kinds of stories, so that people easily find their way into the bigger picture questions that the movie is posing.

You mean the process of dramatizing it?

Yeah, about making it real. I'm reading a book about Gene Roddenberry trying to do this 50 years ago on "Star Trek," and it kind of felt like it applies still today.

Right, right, right. Well, again, I can only just speak from my own experience. Before I worked on that movie "Dredd" that we were just talking about, I worked on this movie, "Never Let Me Go," which is a book adaptation, and it worked as an object lesson for me. Again, it was like American TV; it was like a sort of wakeup call, because it was an adaptation of a book, a very sort of complete book, and we were doing a faithful adaptation. That means syncing into the book, and what I found was, here was an argument -- the book has an argument, it has a thesis, and it has characters and it has themes and it has emotion, and all of them coexist with each other perfectly.

I had come off the back of that, previously, of another film, "Sunshine," where themes and arguments will sometimes just separate, lose touch with each other completely, and then come back together and then separate again. And there was a kind of a lack of rigor attached to it. And a kind of neurotic feeling, which is my fault, which is about, "Shit. I've got to make this adrenalized, or something." Something like that.

When I look back over my working life, I can see it's a sequence of lessons from other people that I'm trying to respond to and trying to react to. "Sunshine" had some noble ambitions, and in some ways does some wonderful stuff. On a personal level, I know it's flawed, but I love the film. In fact, I love all these films, personally. But then, from "Sunshine" to "Never Let Me Go," here's this incredible writer Ishiguro just demonstrating what you can do if you concentrate, in a certain kind of way. This film is unconsciously, initially I think, an attempt to sort of learn that lesson and play it out.

The film is beautifully photographed.

Yeah, Rob Hardy's sensational.

Tell me about that collaboration, getting the look and aesthetic that you wanted and the way that it was captured. It's so gorgeous just to look at, let alone for what's happening on screen.

Well, as with any of the things you can sort of look at in film, there are several components in all of that, and some of them are more obvious, like an incredibly talented DOP and a brilliant production designer and art director, and all those things. Some of them are more subtle. They're sort of like how the grip will slightly adapt the way they're pushing the dolly at a certain moment, or the fact that the gaffer secretly just wants it dialed down a little bit, or unconsciously wants the light slightly softer.

There's all these sort of component parts, and the way I see it, the basic answer to your question is that there is an open conversation. It just starts rolling at the front end of the movie -- and I mean in development -- and more and more people join the conversation and there's a kind of open collaboration between all the HODs and all the people involved. It's about everybody being on the same page, pulling in the same direction -- friends, colleagues -- it's like the vibe. It's not about fighting, it's about working together, and ultimately what that means is everybody is influencing each other. It's very hard, I think on this film, or anything I've worked on, to ever point to anything and say, "It's that's that guy," because we all are in the mix together. Which is what I like about it. I come from books. You've got no fucking friends in books. You're just on your own in the room.

What was the most thrilling challenge that you discovered while making the film, and what was the most daunting thing that you had to overcome?

Honestly, there's nothing daunting about it at all. There was a moment of anxiety during casting, where it was like, "These are the right people do to it. Are they going to do it? Can we persuade them? Is the crazy, scary negotiation between agents and lawyers and managers and producers all going to play out?" That was the only bit where I would find it hard to sleep at night, was that casting period. Because by that point, I'd got so locked into these people that I really couldn't imagine it being anyone else, so it feels like you're in a binary place. There's no solution apart from these people, and if they're not there, it's going to fail. It's not going to exist, even. It just won't be there.

The truth is, I'd worked on some very difficult productions before, and that's been unpleasant, sometimes, but it's a trial by fire. And so, when you're in a production like this, what's to be daunted by? I mean the level of problems you're having to deal with are so, kind of, genial in comparison. It's like, "Should we wait a bit for the sun to come out? Okay, let's wait." It's like that. I mean, it's the problems you dream of. And they don't feel like problems, they just feel like filmmaking. So, it's like all your concentration is into the good stuff. It was by miles the easiest film I've ever worked on. I mean just by miles. And the most pleasant and collegiate. It was just lovely, really.

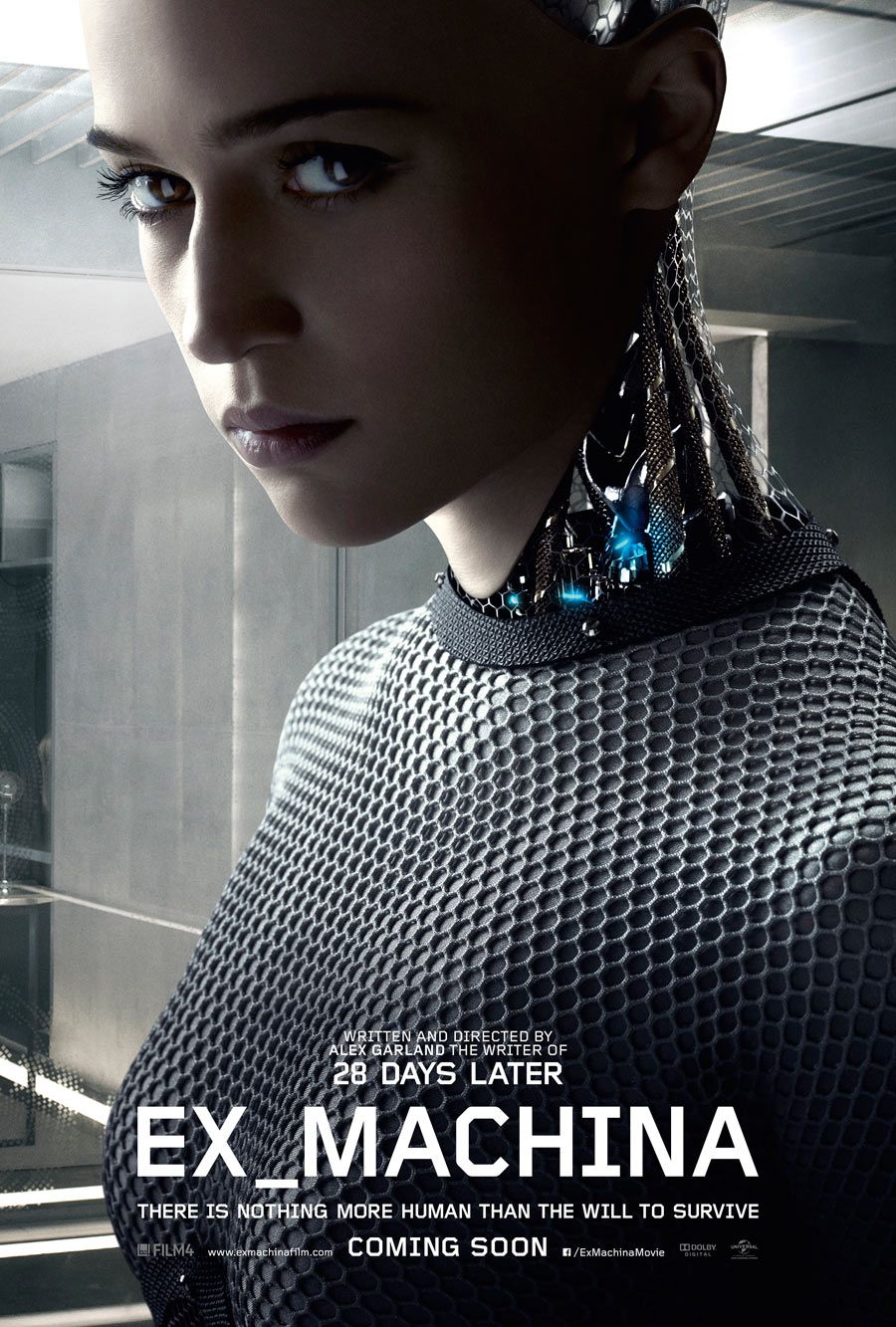

When developing the look of her and demeanor of your central A.I., Ava, what was on your mind?

The first thing that was on my mind, and this guy Jock, who's a comic book artist, from a comic, "2000 AD" and "Dredd" -- me and Jock worked very closely on "Dredd" and we really got on, we had a great working relationship. The first person I'd contacted, the first person who was brought in, outside of the team of producers, the sort of core in that respect, was Jock. He was the first person on the payroll, as it were, and we just bounced stuff backwards and forwards, spent a few weeks just trying to figure out some fundamentals about Ava.

That's quite a pure process, and quite a satisfying one, because there's none of the noise. It's just like a couple of people sitting around trying to figure it out. Initially, as soon as we got going and Jock started sort of sketching this stuff up or working it up, it became clear that the initial problem was going to be avoiding the machines that cinema has created and have turned into icons. Ava first appears as a silhouette, walking onto a screen, and it should be an important moment of contact between the audience and the protagonist -- the sort of covert protagonist of the film. If, at that moment, you think about C3-PO, that's bad. The film is turning to mush in your hands at that moment. And the reason I said C3-PO is because one of the first things Jock sent to me was Ava, with a gold frame. She is different from C3-PO in all significant respects -- except the color gold, and you immediately think of C3-PO. You are there instantly.

And there were some specific other ones: "Metropolis," metallic breastplate? It doesn't matter that most people haven't seen "Metropolis" -- Maria's an icon. You're just there. And the other was more oblique. It was a Chris Cunningham video for a Björk album, with these incredibly beautiful robots constructed out of white plastic, and white plastic was the same as the gold on C3-PO. Most people know that design, because of its subsequent influenced iteration, which was in "I, Robot," so you could say "I, Robot" just as easily, I guess, for audiences, but that was the problem.

When we got our breakthrough was this mesh, where she would have a mesh that followed the contours of the skin of a girl in her early twenties -- but under, like, a spider web was the sort of idea; that under certain lighting conditions, you'd see straight through it, as if it wasn't there, and see the skeletal structure and the machine structure. And under other lighting conditions, like if you turned, a light would glance across that form and you'd see a midriff for a moment and then it would kind of half vanish again. It was the mesh that was, I think, the key part of her design.

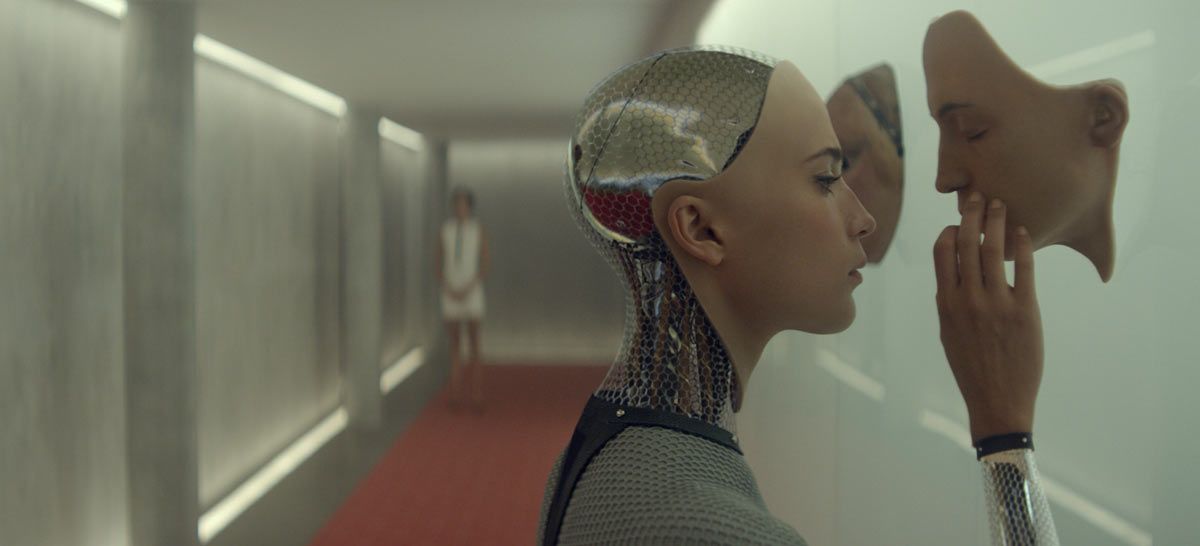

Once you cast Ava, how did Alicia Vikander change the character? How did she make it come alive?

She arrived with an idea, completely of her own volition, which I think she probably didn't know it connected with the uncanny valley thing in VFX, but that was what it occurred to me being most like. Her thing was to act with no robot movement, only human movement, but to do it perfectly, which is essentially the "uncanny valley." And what it does is, it makes you feel sort of "other," and a bit wrong, but it's very, very hard to say why it's wrong. All she's doing is rising off a chair or tilting her head or looking slightly over her shoulder, but it's so perfect, the way she does it, she's got such a control over it, that it takes you away from us, because we don't do that shit. We scratch our chin and slouch.

Yeah, that precision was off-putting in that very subtle way.

It is, well off-putting, like distancing, but also quite seductive. It's doing it intentionally.

You admire the grace, but you notice, "That is so absolutely on point."

Quite. Hopefully that's how it functions. And she just arrived with that as a theory, and as she was saying it, I thought, "Great. Let's do that."