In an era where every would be media company with two nickels to rub together is launching a shared universe of something, 2017 will see the debut of what promises to be one of comics strangest superhero universes.

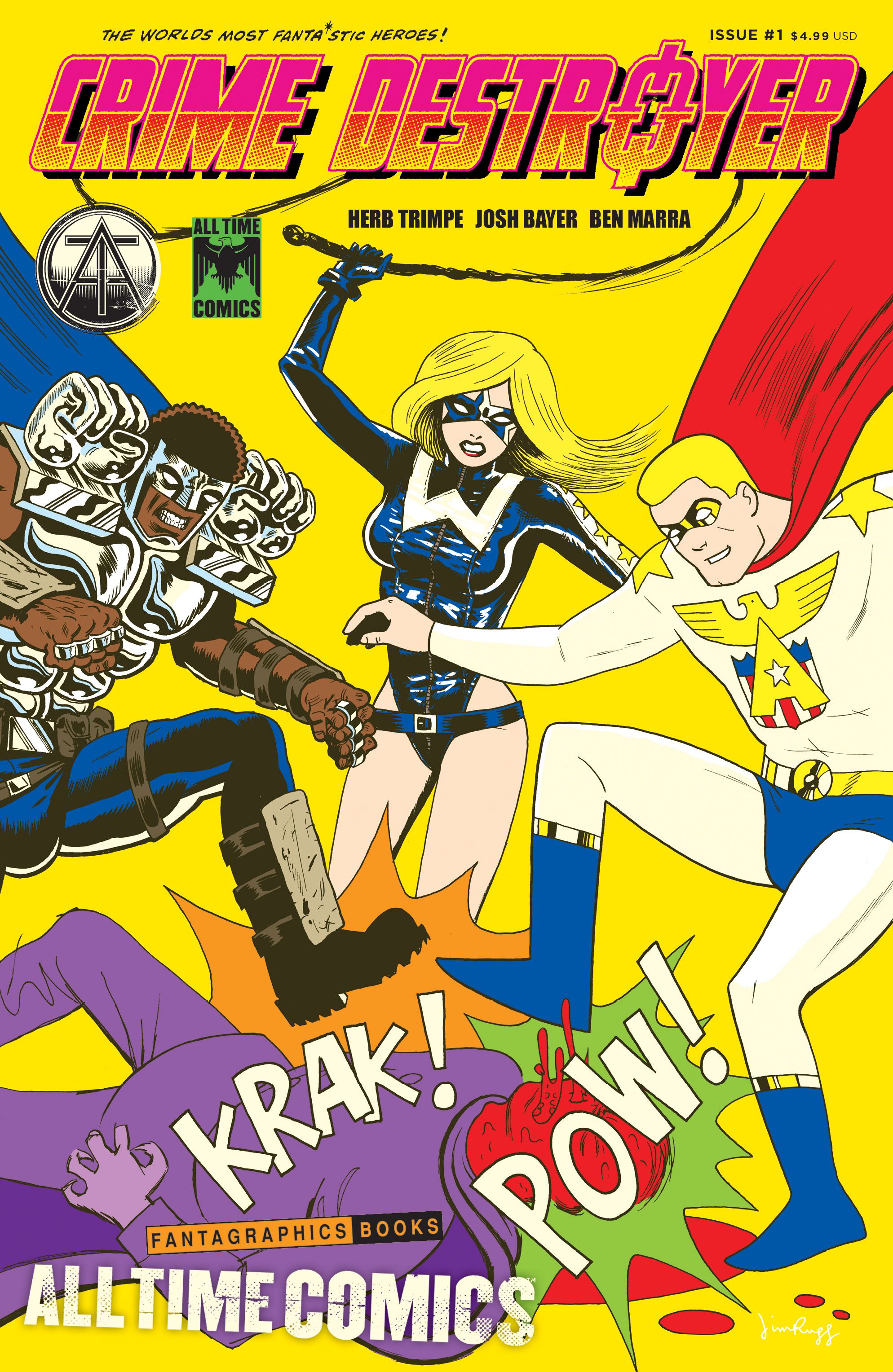

Today, Fantagraphics announced that it will publish a line of superhero books dubbed All Time Comics – a project spearheaded by alternative cartoonist and writer Josh Bayer. Created alongside his brother Samuel Bayer (a longtime director behind music videos including Nirvana's classic "Smells Like Teen Spirit"), the All Time line will consist of six individual but interconnected superhero stories featuring both veteran mainstream artists and some genre-bending cartoonists behind modern indie favorites. The series launches this March with "Crime Destroyer" #1, featuring the last art of longtime "Hulk" artist Herb Trimpe who passed away suddenly last year. That comic will also feature contributions from prolific "Night Business" creator Ben Marra and covers by "Street Angel's" Jim Rugg and "Prison Pit's" Johnny Ryan. From there, Bayer will write comics including "Bullwhip," "Atlas" and "Blind Justice" for artists past and present.

Bayer wrote about his collaboration with the late Trimpe on 13th Dimension, and now CBR has the first interview with the writer about All Time Comics' entire lineup. Below, he explains the origins of his love of superheroes, how talent like Al Milgrom and Noah Van Sciver bring their styles to the universe and the independent punk ethos that will make All Time Comics one of the weirdest superhero events ever.

CBR: Josh, I can't imagine what the initial reaction from superhero fans is going to be to this news (in a good way!). But if I had to guess, I'm sure there are a lot of people who will be wondering (and forgive the language here) whether these are "real" superhero comics. I know that's a super reductive way to label something, but what I mean by that is there's a range of expression for independent takes on this material. You could be playing these tropes straight, doing a loving homage, creating satirical take or just deconstructing the whole thing. Where on that spectrum do you think All Time Comics exists?

Josh Bayer: ALL TIME COMICS (ATC) is a shared superhero universe starring the new kickass, fanta*stic heroes: Atlas, Blind Justice, Bullwhip, and Crime Destroyer. We’ve been really excited to honor the history of comics, both in our stories and in working with legendary creators like Al Milgrom and the late Herb Trimpe; and to create brand new stories and characters with great younger artists like Ben Marra and Matt Rota. Some characters, like Crime Destroyer, have a more "retro" feel because he has such a layered backstory, whereas Bullwhip has no backstory. And it’s been really interesting working with Fantagraphics, since these are their first superheroes, to figure out how to develop these characters from the ground up.

In terms of creating the ATC universe, think of it like this: the first season of a TV show is often a bit strange as the writers figure out the tone. Take the first year of Star Trek, for example, when the writers need to see Spock evolve in a way that becomes consistent with the end of his Characterization.The first album by a band is usually different; it’s like there’s less involvement from outside hands, and there are just guys jamming in a garage. I think both comparisons are apt for ALL TIME COMICS. It’ll be a little like early Motorhead where they are figuring out how much they are a cover band and how much they are an original beast making new material. There’s a wonky, stitched together work of a tailor creating something before your eyes to a book. It’s for other people to say how real the book is. We have a lot of conviction in how we are doing these stories. I wouldn’t call them camp, in the sense that "we don’t really mean this," but sure we have some of the wilderness and loopiness of camp. Ours is not a buttoned up world with a single definition of how comics should be.

I know that you and your brother are working together at the heart of this project. Tell me a bit about the history of that collaboration. Are characters like Crime Destroyer and Bullwhip the kinds of heroes that have their origins in your guys' youth?

My brother Sam Bayer is a film, commercial, and music video director best known for videos like Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” and a lot of Green Day and Metallica videos. Though we’ve always worked together in some fashion, Sam’s work has always been mainstream while mine has always been a bit underground. With ATC we get to take the best aspects of the mainstream (superheroes) and the best aspects of the underground (indie comics and a general rawness) and smash them together.

ATC is a partnership between us. We started this company together, with Sam hatching the idea with me over coffee in the East Village three years ago. He already had Crime Destroyer, Atlas and Bullwhip mostly conjured. Blind Justice came later, which I was glad about because I kept thinking we needed a wild card character -- and then Sam came to me with Blind Justice and handed the raw idea to me to play with. The specific characters were created new for this project, with nothing really left over from our early forays into doing comics.

I still remember my older brothers’ first comics. Sam had a character that he did called Acro-bat, and my brother Jon did a long standing series called Golden Eagle. Both characters were constantly getting mauled and burned and blinded, for example Golden Eagle had his wings burned off in a volcano and AcroBat was carried around by a giant bat for twenty pages in the first issue til he was covered in blood and had most of his clothes ripped off. It was like the psychosexual suffering of saints that kids usually experience in Sunday school, and similarly I found it really exciting and inspiring. I think kids need that type of stuff. I think these days that kids get much of their need to see stuff blow up and people get maimed through video games, and I don’t trust the over-digitalization of that.

I still have so much affection for the roots of comics, seeing pulp action through weird hand drawn art — though I get that digital art has the same root and the same appeal. So, I was the youngest brother, absorbing all my brothers’ influences and I grew up obsessed with comics in general. Sam’s directing career was a direct branch off of his art school experience, and the mentors he found there led him into first illustration and then film. This chance to reconnect with our early influences has been really satisfying. It makes a lot of sense when things come full circle in a way.

Of course, your collaborators in general are a pretty wild group of artists. I wanted to take each cohort on their own terms, starting with a lot of the classic superhero cartoonists who are pitching in. I think names like Herb Trimpe, Al Milgrom and Rick Buckler Jr. all share a common origin point in superhero comics of the '70s and '80s and some shared stylistic DNA. What about that particular era of comics connects hardest with you, and what did you ask of these journeymen cartoonists in terms of updating that feel for 2017?

The whole mission of ATC is to unite and reconcile the gulf between the past and the present in comics. Our aim to try to get older collaborators is no different at all from what has gone on in various decades; Al Williamson, George Tuska, Russ Heath, and Don Perlin had completely different roles in comics in the 1950s than they had in the ‘70s (and beyond), because new creators wanted to work with them. There’s always been a case of the industry having affection and value for the skills of the veterans -- and, of course, there are many horrible cases where these people were discarded, left with no means of support, and had to watch while other people capitalized on their work while they were left to scramble for employment as they began to be pushed out of the industry they helped build.

We rarely asked the veteran creators you mentioned, including Al Milgrom and Herb Trimpe, to update anything about their work. I asked occasionally for creators to BRING BACK a rawness that had maybe been eroded from their work over the years. For example, in Herb’s early pages for Crime Destroyer, he had sort of smoothed out his face and made him more blandly handsome. I asked him to give him more character lines and stress similar to the expressive faces I knew him for, and he brought that look back quickly.

Al Milgrom has had many phases to his career. I love his rawness in the art he did in the ‘80s, where sometimes the art looks scribbly and improvisational, and at other times blunt and impressionistic. I think that Al’s most current commissions had been from employers who wanted a cleaner look. We also got to work with Rick Parker, who is a veteran letterer and artist as well. We also have Steve Bissette inking a pin up over Noah Van Sciver, as he and Noah are good friends. Rich Buckler Sr. wasn’t involved, but his son Rick Buckler was an early collaborator in the project, and I did reach out to him as a salute to the legacy of his Dad’s work.

In particular, I wanted to ask about your collaboration with Herb Trimpe. Like most folks, I was very sorry to hear when he passed, and I find him a real fascinating talent both for his personal story (I end up reading that NY Times piece of his every few years like clockwork) and the way that he evolved his work to meet commercial demand while staying in his own wheelhouse. Still, with a career that went from Kirby-esque classic Marvel stuff to brushes with the "extreme" '90s, what was it in Herb's work that made him the ideal artist for the launch title of "Crime Destroyer," and what was your collaboration like?

Me too, dude. I’m very sad he passed away, and me too: I revisit that NY Times piece repeatedly because it offers insight into his struggle. The honesty, as well as his hopefulness and optimism in that article, is everything I experienced working with Herb. That Herb’s work on "Crime Destroyer" turned out to be his last is really bittersweet. We’re honored, but we would have loved to keep working with him.

I only dealt with Herb through email, and I was thrilled with every new layer of our correspondence. I can’t describe how thrilling it was to get him to sign on when I contacted him about the work. I tried to take it as seriously as I could, and I wrote a very detailed script that was as accessible and clear as possible, to meet the standards of someone who was used to a certain level of professionalism. I actually sent him two scripts, one had a few pages of thumbnail sketches, in case he couldn’t get the description of what was happening from my script. He wrote me saying, “I won’t look at the visuals. I won’t be able to disregard anything I’ve seen. It’s like telling a jury to disregard testimony. Nothing can be unheard.” He was someone who, at age 71, was still a purist about what he did. He was incredibly sensitive, too, and detail oriented, and excited about composition like an artist -- but he was tough minded, pragmatic and professional as any professional craftsman. I liked him a lot.

As far as seeing the things that drove his career all the way through, it was all there. Herb did beautiful classic transitions, and still had all the tools on display at this peak — they were still there. He also once did one of those classic Herb things where I wrote a panel description of a thousand warring druids or something with a thunderbolt blowing up a castle, and Herb just drew a close up of someone’s face instead, and let the dialogue tell the story. It was like, "I’m not drawing that!" He had good boundaries that way, ha.

Similar to the veterans on your team, a lot of the guys who come from the alternative side of the comics community like Ben Marra and Jim Rugg share a sensibility of revitalizing (both lovingly and satirically) the visual tropes and cultural themes of 20th century genre madness. Though others in the group like Noah Van Sciver have scarcely worked in this style at all. How does the All Time Comics project channel that kind of energy? What were the watchwords you guys had as you were putting this together – the big visual or genre idea that helped make these stories come together?

Everyone had a different way of working. Ben is one of my favorite artists period, and Johnny Ryan has inspired me to make comics more than anyone for the past 15 years. They have that ability to hit the id that is so life affirming and makes you believe in comics’ simple power to bypass the brain and connect at a gut level, that it makes you believe you can make comics, too. Ben can find infinite variations on the classic formula of making comics, borrowing echoes of the bronze age, and pulp tropes. Ben co-designed Bullwhip with me, and I just found some of his original designs for Bullwhip, and they are all completely crazy and great. One involved her having fabric in her hair that spelled out BW.

This wouldn't be a superhero comic interview if we didn't talk about your wild characters and their bizarre powers. From Bullwhip and Blind Justice to Atlas and Crime Destroyer, the feeling I get from the names at least evokes that great capes-and-tights idea of unhinged vigilante justice. What can you tell me about these guys conceptually and in terms of how their stories are shaping up?

The Blind Justice book is maybe my favorite to write. His Tag Line is, “The man who walks through bullets.” He’s like a true holy roller, a fanatic for crime fighting and justice. He may be delusional. He believes he’s bulletproof. No matter how many times he’s shot, he just wraps his wounds up after the battle and forgets it. In his secret identity, he remains way under the radar by healing up in a convalescent home for people with brain trauma, where he’s been a patient for years. He sleeps in a ward of patients in anonymous beds, and spends his days vegetating. This home is part of the retro quality of the comics because in one of the issues we see how the place is barely staying open. It’s exactly the type of place, a mental health center and halfway house, that was endangered by Reagan’s policies aimed at stripping away public assistance.

Bullwhip is really interesting because she’s like Cher or Madonna. She doesn’t have a backstory or a secret identity, she just is Bullwhip. This lack of history actually makes her more exciting to write about because her personality as Bullwhip just seems to glow brighter, knowing she’s not concealing one personality behind another. Also, the world around her is even weirder than the ones around the other characters. In her comic, she has a coven of time vampires she grapples with, as well as her arch villain (and favorite punching bag), the Misogynist, to fight.

Crime Destroyer is an urban vigilante all about revenge, driving a souped up car with weapons. He also has an in-depth history that weaves through different eras of comics, and from the Vietnam era to the present. He comes from tragedy and loss, and there’s always room for stories about the single vigilante obsessively waging a war on crime while journeying through hidden underworlds. Crime Destroyer is constantly butting heads with city commissioners and other bureaucratic figures, as well as racist extremists like Scarlet Dragon, and mercenaries like RainGod.

Atlas is our most super powered character. He has traces of all kinds of iconic stories to him. Stories of red, white- and blue-colored flying heroes in capes have been referenced, as well as older adventures involving kid explorers, uncovered lost civilizations and ancient gods who leave ancient weapons behind to be found by worthy heroes. Atlas is also in the tradition of heroes who have fatal weaknesses that constantly threaten to steal their abilities. His mortal weakness is fear, when he becomes afraid he loses his connection to the source that powers him.

So All Time Comics is a universe of its own, and while a lot of these titles will be one-shots, I get the sense that everything you and Fantagraphics are putting out will be connected in that structurally inventive "Morrison-esque" manner. What's your view on the big picture of this story? Did you want to do your own take on the massive superhero event in some ways?

Yes, we sort of wanted to offer our own take on the massive superhero event. Generally, ATC is more focused on the heroes as characters than events. I fondly remember Marvel’s "Secret Wars" from when I was 12. It was exciting then, and some of the events are still exciting. I think more of Alan Moore’s unfinished 1963 book, which was building towards an event he didn’t get a chance to write. That’s the type of thing that we look at as guiding inspiration for us in doing ATC.

Overall, what do you want the kind of superhero reader who may be unfamiliar with your work or your view on superheroes to know about this project and its goals? What to you is the satisfying creative outcome when all is said and done with these books?

There’s been a major cultural shift towards superheroes being embraced by the American public -- but so often the comics are forgotten. I want to remind people that comics aren’t going anywhere, and that drawing and writing is done by people not by a committee. That once there were cheap comics that were fun, and had ads for shitty sea monkeys in the back, and X-ray specs. All those things were great. Dee Dee Ramone used to have a comic in his back pocket that he’d read while he was turning tricks at 53rd and 3rd. Dee Dee’s gone, 53rd and 3rd is covered with CitiBanks and Panera Bread, and it’s up to us to remind people what was punk and fun about comics.

All Time Comics begins in March from Fantagraphics.