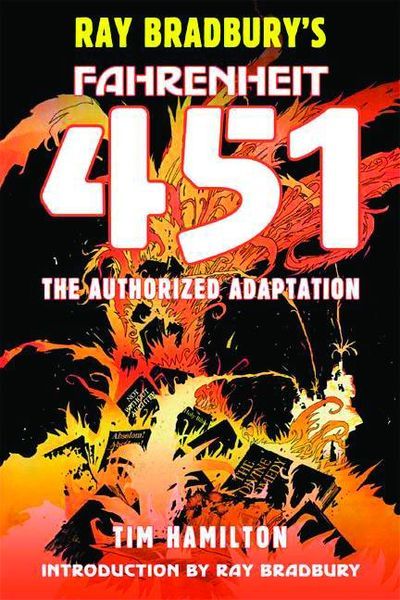

Writing for Slate, Sarah Boxer (who, it should be noted, is a cartoonist in her own right) penned a review of Tim Hamilton's adaptation of the Ray Bradbury classic Fahrenheit 451 that — initially at least — seems flummoxed by the whole "graphic novel boom" thing:

It's hard to know what on earth Bradbury was thinking. Did he just give in to the enemy? And what was the artist, Hamilton, thinking, when he illustrated the fire chief's rant with his own tableau of degraded books: Hamlet for Dimwits, Time magazine, and, yes, two Classic Comics editions, Moby Dick and Treasure Island. (Hamilton himself illustrated a comic-book version of Treasure Island before taking on Fahrenheit 451.) It's as if author and artist were vigorously waving a white flag and shouting, "We couldn't beat 'em, so we joined 'em!"

Later on she adds:

Graphic novels may win some new readers, but the text is almost always shortened to make way for pictures, and what survives of it is radically different: It's mostly dialogue, like a screenplay. In the graphic-novel version of Fahrenheit 451, almost all of the words are spoken. Even the pictures confirm that the novel has become a script.

By the end of the review, however, she turns around and suggests that Hamilton's adaptation was more in keeping with Bradbury's own interests in the medium and the book's larger themes. It's all very confusing.

Still, who reads all the way through an article these days? The damage was done and the review was muddled and grumpy enough to incite a firestorm in the comments section:

I'm not going to try to quote every noteworthy comment here — life's too short. Suffice it to say most of them can be grouped in the following ways: a) Bradbury loves comics and has been adapted in comics since the '50s with EC, so nyeah; 2) Boxer should read Watchman! Or Maus! No, Persepolis! Sandman! c) Graphic novels should be solely reviewed by people who like graphic novels; and d) FU Sarah Boxer! Stop being a hater!

What interests/concerns me is not so much Boxer's take on the Fahrenheit adaptation or even her vague disdain for the medium as her seeming insistence, as shown in that second quote, that words paired with pictures inevitably results in an inferior product compared to a novel.

It's balderdash of course. While bad comic adaptations of classic books are a dime a dozen, there are enough good ones (like City of Glass) to put Boxer's lie to rest. The key is in letting the art tell the story.

It's a point that NPR's Glen Weldon puts more eloquently than I really could:

Let me try to put it more concretely: In the best graphic novels/comics/sequential art/whatever, the art doesn't just sit there. It doesn't simply illustrate what the words are describing, because comics are more than just books with pictures.

No, the art takes over a share of the heavy lifting. It does its own, independent narrative work: it characterizes, sets the tone, advances the plot, etc.

The art, in other words, gets off its damn butt.

Go and read the rest of Weldon's essay. It's not just a perfect encapsulation of what makes a good adaptation, but also a primer on how to write for comics in general.