Writer Bryan Q. Miller says the iconic Space Mountain ride -- first introduced in 1975 at Walt Disney World in Florida, now in all five Disney parks worldwide -- scared him out of his mind as a kid. Artist Kelley Jones isn't a fan either, telling CBR that he's "terrified" of roller coasters.

Yet that didn't damper Miller ("Smallville," "Batgirl," the upcoming "Suicide Squad" episode of "Arrow") and Jones' ("Sandman," the Elseworlds Batman vampire trilogy) enthusiasm for teaming on a graphic novel trilogy based on the ride. In the tradition of the massively successful "Pirates of the Caribbean" films (and the considerably less successful "Haunted Mansion" film), "Space Mountain" takes a famous Disney park attraction and makes a story out of it. But compared to similar past efforts, Space Mountain the ride doesn't exactly suggest a whole lot of story, other than a futuristic motif -- it's less than three minutes and mostly in the dark, after all.

So that left Miller and Jones with plenty of room to craft their own story inspired by familiar Space Mountain and Tomorrowland trappings for the book, scheduled for release on May 6 and the first of three planned original graphic novels -- the first OGN in Disney Book Group's new Disney Comics line. (Disney's official copy says it's aimed at ages 8 through 12, but Miller says he didn't write with any specific age group in mind.) "Space Mountain" is set in 2125, and stars Magellan Science Academy cadets Tommy and Stella, who become entangled in an adventure -- not through space, but time. CBR News spoke with both Miller and Jones in this exclusive first interview about "Space Mountain," which the writer say has "so much" potential as a fictional landscape.

CBR News: Bryan, Kelley, as the creative team behind the "Space Mountain" graphic novel, how much are both of you fans of Space Mountain the ride, and did any research involve a trip to Disney parks?

Bryan Q. Miller: We take the bits and pieces. Not wholly dissimilar to how the "Pirates of the Caribbean" franchise started with the hallmarks of the ride as little cheeky nods and Easter eggs in the movie, like the dog with the keys, "Space Mountain" is part of the larger pastiche of a whole wing of the Disney parks. I was 8, I think, the last time I rode Space Mountain. I'm not a big roller coaster guy, so it kind of scared me out of my mind when I was little.

Having walked through the park, it definitely was our goal to bring to the project that same sense of when you walk through Tomorrowland -- it's like you're in futuretown. I think Kelley really, really hit that well. Even though it's not a physical representation, elements of the various parks are worked into the visual side of the story. The narrative uses those elements, but puts them into its own story.

Kelley Jones: I'm terrified of roller coasters, so I wasn't going to do anything with that. For me, it was more or less trying to bring that same atmosphere, and use certain aspects of the park as set-pieces -- and then throw in a lot of extra stuff.

I really just wanted, frankly, to have a fun comic book, with a lot of imagination. I'm a big adherent to that. I see this as an all-ages type of a thing. I'm around a lot of kids, and I don't see them really getting into [comics] the way I did. And it's not that they wouldn't. It's very inaccessible now for kids. I go to shows, I don't see kids. In the '90s, they were everywhere. I have kids now. If you ask them who their favorite artists are, they're going to say Kirby, Ditko, Buscema, all these people, but they don't really talk about modern stuff, because they don't get it. I'm dealing with a 13-year-old, and he will go on and on and on about Steve Ditko, and he's not really into the new stuff. It's inaccessible to him. So it started a long time ago with Mike Siglain, the editor on this. And it doesn't mean writing down, or anything like that, it just means inclusive, and that you have a lot of adventure and fun. That doesn't mean a lack of drama, or a lack of seriousness.

Certainly, I have done a lot of very dark stuff, a lot of very serious stuff. I still am doing that. Creatively, I want a lot of range. I've always had an affinity for this kind of stuff. After a while, you do enough scary stuff, that's all they're going to ask you to do. If you do enough Batman, that's what you do. I've waited for an opportunity like this. When I read [Miller's] other work, the one thing I liked was that I could read it and enjoy it, and it didn't matter the age, the sex, anything. It was just a good story. That's really hard to find.

Miller: With Kelley, because he is known for that grittier, darker stuff, it's a delight when you have that expectation and then you get into the art for the book and it's not [that] -- but then also, because that's in Kelley's tool kit, there is a portion of the book where they do believe that there is danger, because there really is, it's not out of left field; it all is of a piece. It made everything more real, and not in a scary way, but in a way that you were able to empathize with the kids, and what they're going through in the book -- the adventure and the danger.

Jones: if you're going to show different things -- different worlds, different vista, whatever that is -- ultimately, they have to be interesting. You want to make people turn the page. You want to also exceed a certain amount of expectation. It's funny, because when I first started my career, it was sci-fi, and people were stunned when I went on to do horror books. Then when I went on to do Batman -- from "Micronauts" to "Deadman" is a big leap, then from "Deadman" to Batman, it went to film noir.

There's a lot of stuff I was very influenced by growing up, and one was Wally Wood, who could simply draw anything. I always wanted the range of it. I want Bryan to feel comfortable that anything he writes, I will draw. He doesn't have to be hamstrung by my personal desires, or any kind of limitations. You write it, I draw it. And that's where the fun comes in.

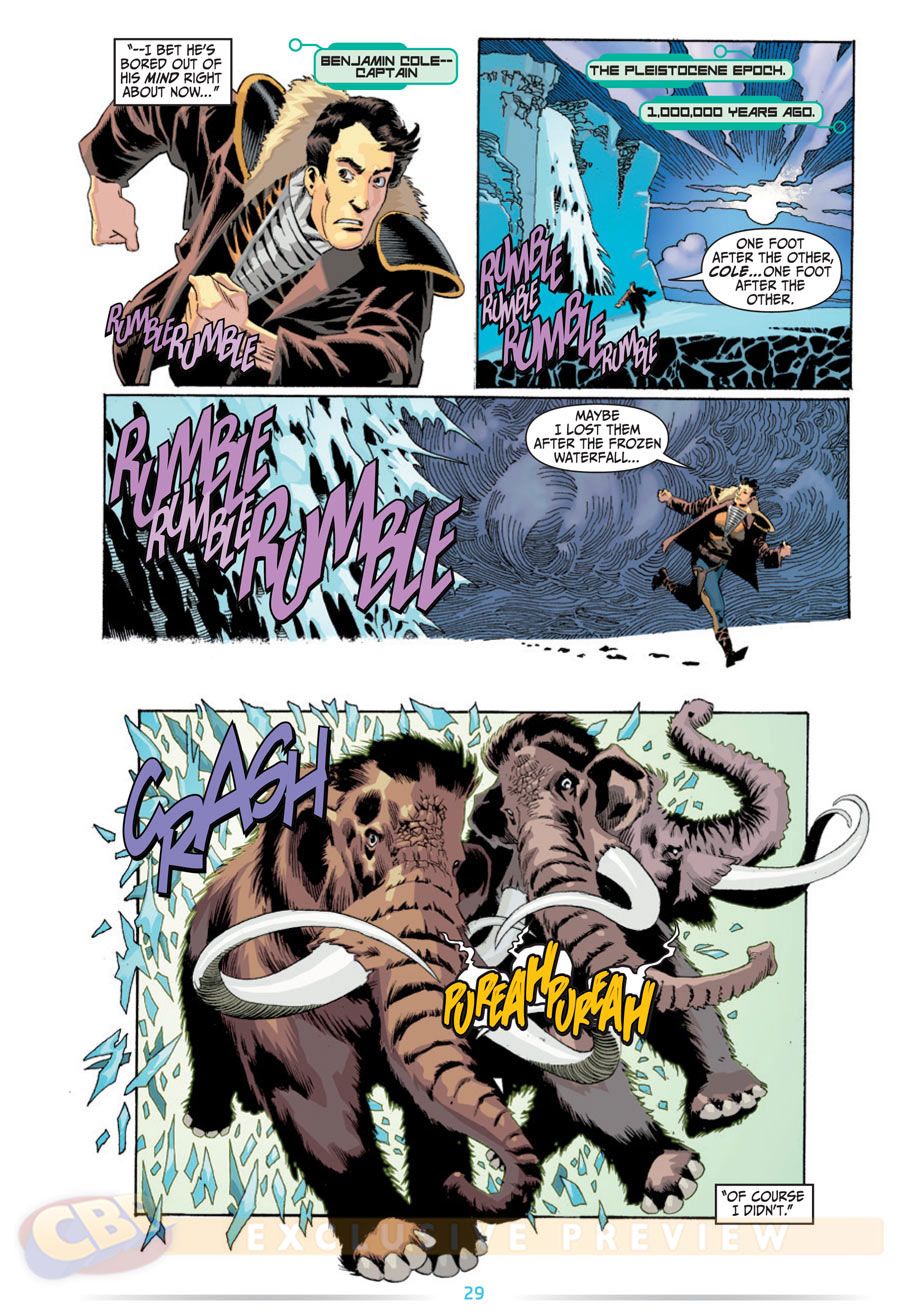

Miller: There's a full range of stuff, too. Historical stuff, dinosaur stuff, action/adventure stuff -- there's some physical comedy stuff with the kids two-thirds of the way through the book where they have to sneak into a place, that was a spur of the moment writing thing that [Jones] pulled off beautifully.

Jones: If you're a fan of comics, or a well-written story, this is it. I don't say that arbitrarily. I have been looking for things like this to do, and it's hard to find. The last thing you want to be as a creative person is bored. ["Space Mountain"] is over 150 pages, but it moves and moves and moves. It has all the components that frankly you don't see as much anymore, and not because they don't work, and not because they're out of fashion -- [because] it's hard work.

Miller: We have the unique opportunity here with this to present it in longform. It's not broken up into monthlies from the top. We had the chance to really dig in and tell the story start to finish, with it all laid out. There were no surprises along the way.

This is in the original graphic novel format, which pacing-wise, seems more freeing, but there's an even bigger mythology here -- this is planned as a trilogy, correct?

Jones: All of the work on the [next] one is going on right now.

Miller: We're in our next giant phase of orchestration for where the world of "Space Mountain" goes next.

There's obviously a history of taking Disney rides and building a bigger story out of them -- but for a story that's going to end up being around 400 to 500 pages, what's the starting point there? How did that develop, story-wise and visually?

Miller: Mike wanted to take a swing and do kind of a throwback, kids' sci-fi adventure thing. "Space Mountain" was there for the taking. It's a Disney property. It's their stuff. The Imagineers were all looped in to design [and] narrative points, because it's linked intimately to the park, a place people have visited, and rides they've been on. Disney takes a lot of pride in that brand. Coming into "Space Mountain" with having things like [former Tomorrowland attractions] the Moonliner and the Astro Jets and the World Clock, all those things, they were very careful about appropriation, misappropriation, what things could do, what things couldn't do. Which can be at times vexing, but at the same time, it helps. It's part of that orchestration -- it's an all hands on deck thing where you're getting guidance from the folks who were involved with creating the toys you're playing with in the first place. Narratively, there was some impact, and visually, there was a larger impact, just in how things specifically had to look, and there were some tweaks that happened along the way. But it was cool, just getting to know the Imagineers were looking at your stuff, and reading your stuff, and liking your stuff.

Jones: I was trepidacious. You go into it thinking, "OK, they're going to tweak and twist" -- other than what we had to do for the story, I didn't run into any difficulties.

Miller: While this was happening, the feature development of Brad Bird's "Tomorrowland" movie came up, so there were a few things just to make sure wires weren't crossed, that elements of brand weren't used in two places, so certain things had to be tweaked from a narrative standpoint. But by and large, it's been absolutely great.

Unlike "Pirates of the Caribbean," aside from the visuals of the ride, there aren't as many Easter eggs to pull from. With "Pirates of the Caribbean," clearly there's an island under the siege. With "Space Mountain," they let us weave our own tale using the toys in the sandbox.

Let's talk more specifically about the story -- surely you don't want to give everything away at this point, but what can you say about the development of the two protagonists, the students at the science academy, who appear to drive the story?

Miller: They're definitely our eyes and ears into the world. We're in the future, there's a space colony on an asteroid in orbit of the Cygnus X-1 black hole, which if I remember my meager education as a child, is a real astronomical phenomenon.

Everyone has a dream. Tommy is the one who tends to leap without looking, very much just wants to be a space ace. He's at Magellan Science Academy, and he doesn't really care so much about books and studying, he wants to shoot from the hip and go with his gut. His opposite number -- its oil and water at first -- Stella is very much by the book, knows all the facts but not really the application. She's not a born adventurer, but has tons of potential.

These two wind up being, through circumstances we can't quite get into, thrust into this adventure with the crew of the Moonliner 7. Space Mountain's purpose is, not unlike original "Star Trek," one of peaceful exploration. But not of space itself -- we've already gotten out to a black hole -- it's of time, it's of our history and our past. There's a crew, including Captain Cole, who's the dashing, Buck Rogers-esque space ace that Tommy one day would hope to be. He leads these missions into the past, to observe and record stuff in history -- naturally, things go sideways.

They win their golden ticket for the first-ever trip to the future. It's the test flight, just 24 hours into the future. As happens with creations such as these, something goes wrong, and then it's up to our two heroes -- in a very Amblin-y, early '80s way -- put their heads together to save the adults, and the day.

Jones: The first part sows the seeds of much bigger things. I think when Bryan was told that there would be two more, that's when he started planting a lot of those seeds. So there are a lot of very cryptic things going on, as well.

Miller: Tonally, it's very much of an earlier Disney time. Kelley's art evokes "Escape to Witch Mountain," but also "The Black Hole" -- in the Venn diagram of what kind of thing this is, it falls within the happy child of the "Witch Mountain" series and "The Black Hole."

Jones: The old Disney villains were scary to me when I was a kid. Some of my most traumatic events from my life as a kid were certainly some of the Disney animated features. Bad things happen.

Miller: But not traumatic. If your seven-year-old reads this, they won't be traumatized.

Jones: It's that good kind of scare.

Miller: When you watch "Sleeping Beauty," you know Maleficent isn't messing around. She's dangerous. When Pinocchio gets turned into the donkey at the amusement park, it's a scary thing and there's a lesson to it. You have to have moments like that, and Kelley's art totally sells it.

The story takes place 100 years in the future, and you've mentioned taking visual cues from Tomorrowland, which is very much a retro-futuristic type approach. Is that influencing -- if not defining -- the approach to the future in this book?

Miller: Mike sent me a box set of old Walt Disney specials about what the future would be like, and how things in the future would work. That vision of the future from then, from when Tomorrowland was first created, that was that hopeful optimism that anything could happen, and that's the starting point for this take on the future.

Jones: For me, it was just my sheer love of those films, and that perception of the future that didn't happen from the '50s and '60s. I also wanted to have that "2001" thing where you also have some stuff that does work.

It's a shockingly huge amount of work, and I'm still stunned that it came out as connected and correct as it did.

You've mentioned the attempt to make "Space Mountain" something a little different than what's on the market right now and truly all ages, but more traditional comic book fans will know both of your work from high-profile superhero comics -- what would you say this book offers to them?

Miller: It's not that we didn't approach it as a comic book, but it wasn't specifically pegged into any one corner when we were making it. When I was writing it, I was just writing it. It wasn't something that was written to any specific age group, any specific genre group -- if you're someone who just likes space adventure, and is missing reading some space adventure in your monthly haul, this is that comic. If you want to share something with your kids -- like Amblin movies, like the Disney movies from when you were little -- this is the feel of that, too. Even not intentionally, the nature of the project lent itself to pulling in people from all of those pieces of the Venn diagram to give them something we hope they can all enjoy in a very different way.

And it's a quality production. Often you'll have things that are tie-ins -- and this is not a Disney thing, just in general in life -- to video games, or different movies, and there's not a lot of care put into it. This is something that from the first moment of editorial all the way through the last moment of lettering, there's a ton of care put into this book. It's not something anyone didn't take tremendously seriously.

Jones: It has to be very true to comic book roots. I didn't want to do something that couldn't stand against anything else. You have to hit your mark.

It sounds like it was pretty natural for both of you to derive a lot of mythology from a two-and-a-half minute ride that's essentially completely in the dark.

Miller: And there's so much more that has yet to be even addressed. We get to do so much more with the universe that we, with care, slapped together for that first book. Now we really get to get into the meat of so much stuff with book two and beyond.

The first volume of "Space Mountain" is scheduled for release on May 6 from Disney Comics.