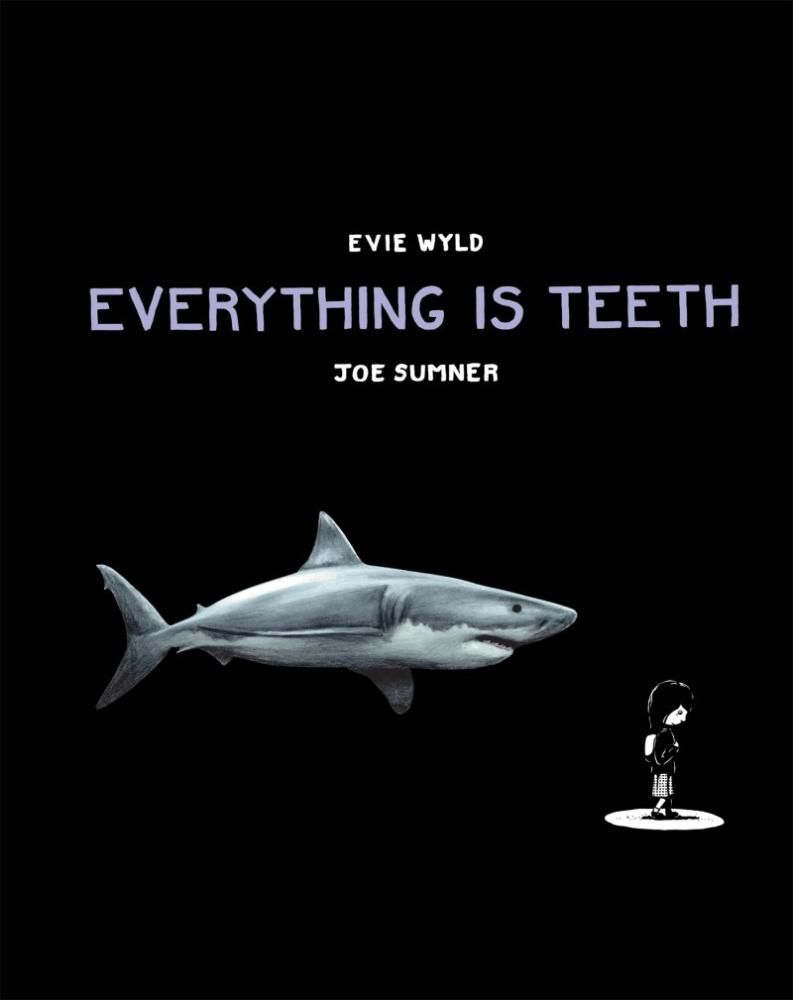

Evie Wyld is one of the most acclaimed novelists of her generation. Her two novels, "After the Fire, A Still Small Voice" and "All the Birds, Singing," have received many awards, she was named one of Granta Magazine's Best Young British Novelists in 2013, and she's been shortlisted for the Dublin International IMPAC Prize, the Orange Award and many others prizes. Her work is lyrical and atmospheric, suspenseful, complex and haunting -- and few people expected her third book to be a graphic novel.

"Everything Is Teeth" is a graphic memoir, illustrated by Joe Sumner. As a child, Wyld traveled to Australia every other summer with her family, where she became fascinated and terrified by sharks. Now, she exploring that topic in her new work, where it should come as no surprise to readers of her novels that she and Sumner masterfully convey a child's perspective on nature and on family life.

CBR News: I'm a great admirer of your novels, so just as a first question, I wonder why you decides to make a graphic memoir as opposed to writing a prose piece?

Evie Wyld: I've wanted to do a project with Joe Sumner, the illustrator, for quite a long time. We're very old friends and I'm a big fan of graphic novels -- especially memoir. I went to art school and discovered that I wasn't a great drawer, so I gave it up and took up writing instead. But I've always felt this kind of longing or impotency reading [graphic novels]. I'd love to be able to communicate in that way.

It was a really fun thing to do, and it completely changed from when we started it. Neither of us had done anything like it before, so we didn't really know how to approach it. And neither of us is particularly good at working with other people. [Laughs] I gave him some writing, and then he drew some pictures from that and then I looked at the pictures and gave him different writing. It actually started out as a short story, and then became a memoir. It took seven years, alongside other projects, so obviously life changes a lot in that time. [Laughs] It just gradually became more and more the story of Australia and sharks and my dad.

Has that ever happened to you before? Have your novels changed a lot from your initial conception of them?

Actually, yeah, I do find that quite often. With me, anyway, things take such a long time, you're a different writer by the time that you finish a draft. You go back and you think, that's not how I would have seen that. You could endlessly write the same novel, but I find if I ever start a novel with an idea, almost always that gets chucked out the window, three-quarters of the way through. You just go, okay, and now, junk the whole starting point. The thing I'm writing at the moment started as looking at my English grandmother, and now it's about witches instead. There are some similarities. [Laughs]

Having read your books, you present Australia as this wild place, which is how you experienced it as a child.

It's definitely an outsider's view. It's nostalgic as well. I remember being interviewed by an Australia journalist who said the point in my first book when she realized I wasn't an Australian who lives in Australia was when I got squeamish about ticks. [Laughs] There's definitely an outsider's point of view, I think. English people in particular are convinced that if they go to Australia, several things at once will kill them. I love that. I mean, several things at once in the UK will kill you if you find the right place and time -- it's just, they're usually people. I like thinking about landscape, and how a person changes in a different landscape. How somebody behaves when nobody else is looking. I think that's more possible in Australia, the big spaces, the wide openness of it.

Besides that notion of wildness, there's a terror and awe in your book, which I always associate with being a kid, but I think it's still there for most of us.

It's worse now, because when you're an adult, you have to pretend not to be afraid. I've always been fascinated by horror. It's always interesting to put a character in a situation where the cracks will start to show. I guess it's a natural thing to put them in danger, whether natural or urban. I look to Stephen King, and loads and loads of horror movies I was into as a kid, and I think it's the uncanny, really, that I'm interested in. The little ruffles in every day life. I think the scary stuff in my second novel -- the British scary stuff -- is so much fun to write because it's apparently not a scary landscape. It's a sad, quiet landscape and sheep are benign. But I don't know if you've ever walked through a field at night and had a whole field of sheep turn to look at you, well, there's something really unsettling there. [Laughs]

Did you play a role in the decision to render the sharks so realistically in the book, because the people are drawn in a simpler way.

I think that was something Joe had in his mind from the very beginning. It really is a collaboration. Being the writer, it's heavily weighted to the fact that it's "my" book, but it really is a joint project. Joe had in his mind originally that he wanted the sharks to be realistic. Most of the depictions of sharks you get are either cartoony, or they're over-scary, and the whole point of the book really is that they're just doing their thing. They are quite scary-looking, but that's nothing to do with their personality. [Laughs] I think the cartoonishness of me as a child being completely blank-faced is nice as a kind of lens. It's very much how I felt as a child. I was extremely shy, and I never spoke much. I was just in the corner watching.

It works so well, because that otherness is so starkly rendered.

One of the reasons it was lovely to do this book was that it's kind of the starting point for my creativity and my writing. Australia, and that part of my young life, was when I felt like I had the most open imagination. It's the place in my life that has the most sensory memories. I basically lived for the times we went to Australia, which was once every two years. I'd dream about it, I'd daydream about it, I'd fantasize about going back there. I think that's one of the reasons that sharks loomed so big in my life, because they were so totally different from anything we really had back home. Then there's the thing that happens with childhood where you misunderstand things in your imagination. To me, all sharks were the size of a double decker bus. I think actually a lot of English people assume they are that big and there are that many of them that you dip a toe in the water in Australia -- it's over. [Laughs] Which is an enjoyable thing to keep telling them. [Laughs]

Was that child's point of view at the heart of the story from the beginning?

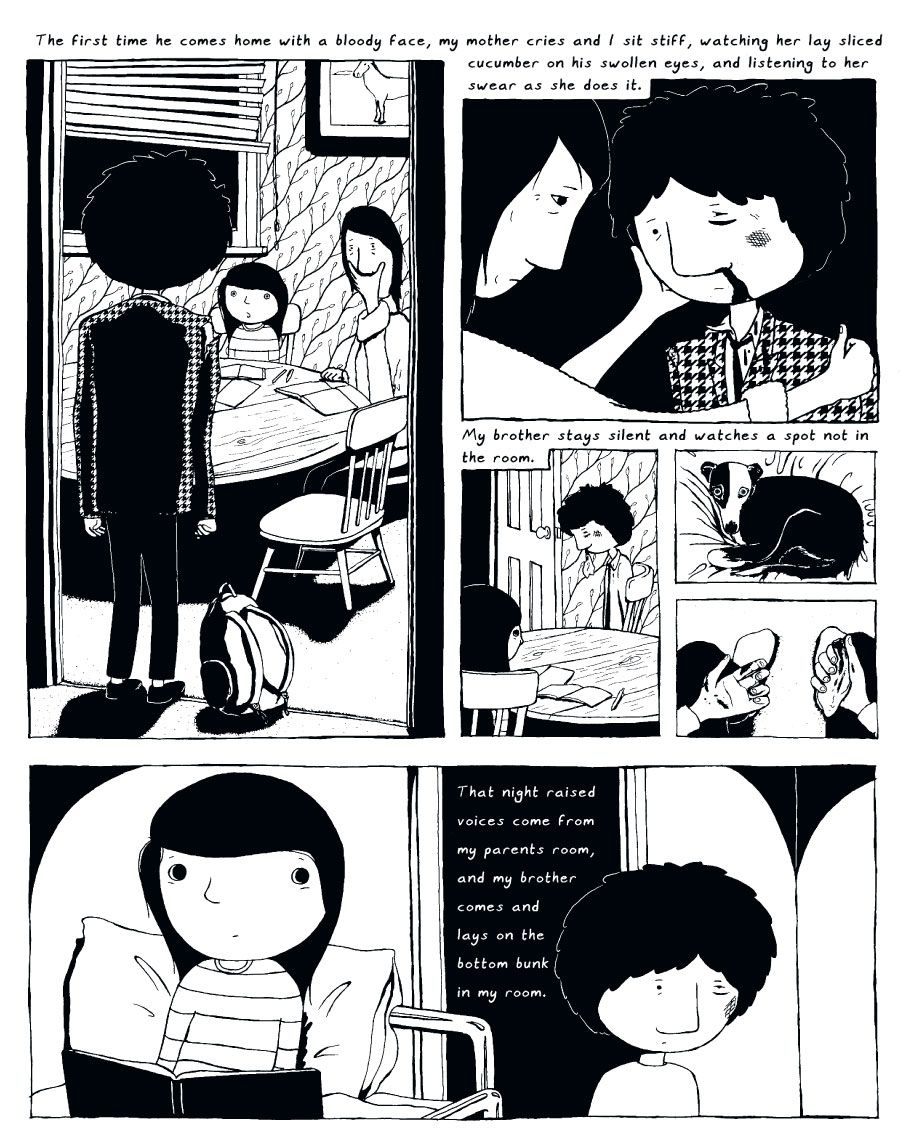

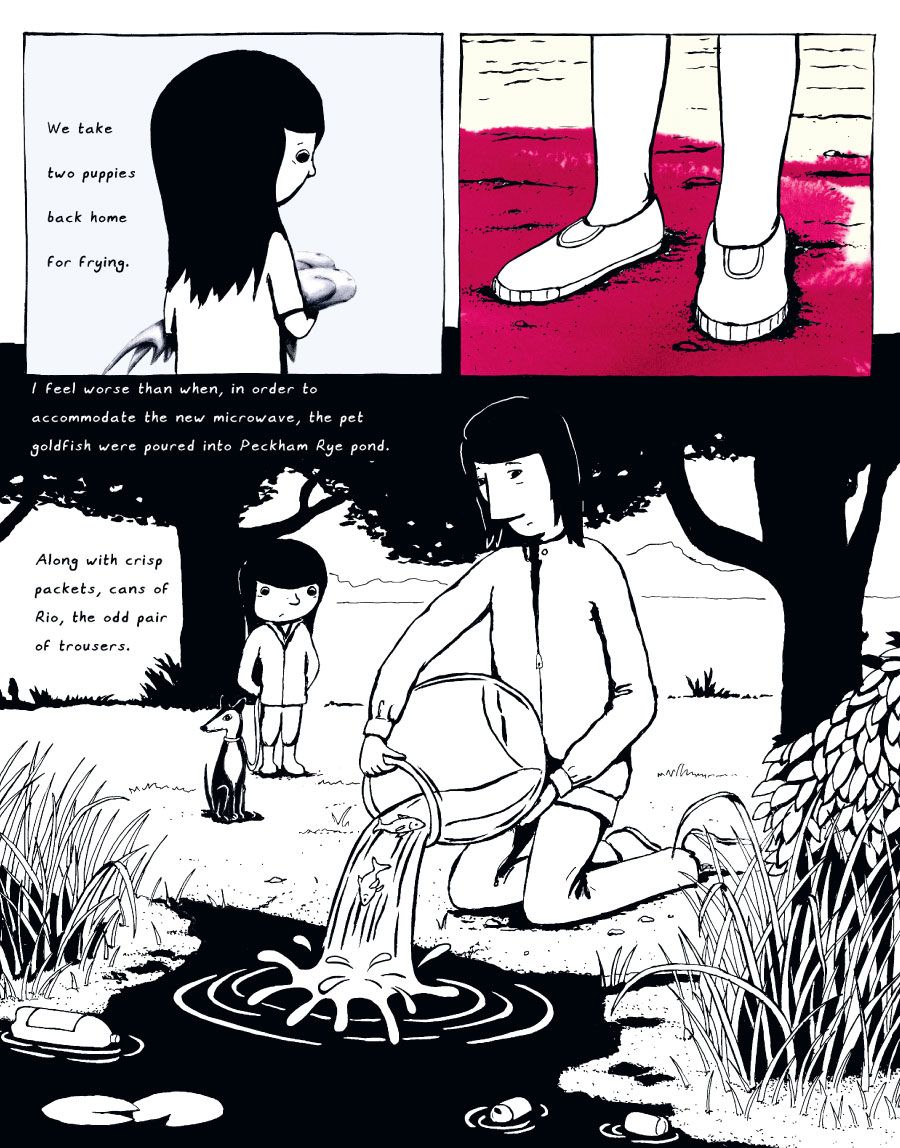

I wanted it to feel like a child's eye view. There's a lot of stuff going on between my parents -- the awkwardness of my father not enjoying Australia, my mother being homesick in the UK, my brother getting beaten up and not really getting on at school. To me, as a child, that was one-dimensional. It was just some events that happened, which as an adult I recognize as part of a much larger thing. I wanted it to be a child's perception because then you're able to go into the child's fear of sharks and misunderstandings. Sharks were one dimensional as well to me. They were just monsters. They weren't up to any good.

How has your relationship to sharks, and to Australia, changed?

I came around to sharks when I was 14, after I got over being terrified of them and realized that they're an essential part of our ecosystem and the food chain. Then, your eyes get a little more open to things like shark fin soup, which is just obliterating them. It just became more and more interesting that they are this last monster to humans. We're embarrassed to say that we don't feel like we've mastered the seas yet.

About two years ago in Perth, in Australia, they were doing this horrible shark cull. They anchored quite close to the swimming beach and baited a hook which drew sharks in, and then they would pull them up and kill them because somebody had been attacked nearby. It just is the most thoughtless, stupid thing I've ever heard of. Attracting sharks to a swimming area and killing them because maybe that was the shark that attacked someone two weeks ago. The fact that we use the sea for recreational purposes and the things that live in it, we're like, you need to leave so I can have a splashabout in safety. It's just completely revolting. I think it speaks to the worst elements in human beings, that they would just destroy something that they don't understand. That happened while I was still working on the book. I didn't want this to be an eco book. I wanted to address the fact that I was genuinely terrified of them and at some point would have happily pressed a button and wiped them all out, but coming to terms with the thing that you're most frightened of is a good thing.

You really capture that terror of sharks, but unlike in, say, "Jaws" -- I grew up near where it was set and filmed -- you never turned them into a caricature of a monster.

That was the aim, really, to write something about sharks that was frightening, but also just truthful. I mean, "Jaws" isn't truthful. The human relationships in "Jaws" are amazing, but the shark stuff, you just have to look at the shark to go, that's a daft looking creature. This was just an effort to talk about sharks as they are and as they're perceived. I love the film. I think it's got some of the most amazing script writing. I had Quint's speech read at my wedding. [Laughs] I'm a big fan.

You mentioned that you're a fan of graphic memoirs. Are there any you especially love or were helpful as you were thinking about this book?

I love David Small's "Stitches." I think that is just incredible. "Epileptic" is amazing. Obviously, Alison Bechdel is really incredible. "Fun Home" was really useful in looking at a child's eye view of your family. I guess those are the main ones. I love Jeff Brown's memoirs. He's hideously honest. [Laughs] The graphic novel market in the UK, it's a little trickier to get ahold of the more out there ones.

One reason I ask is because I know that you run a bookstore, Review, in London.

I used to -- until I had a baby. Breastfeeding at the tills is frowned upon. But I'm still a partner, and I pop in there a lot.

What's like working at a bookstore while you're writing and publishing?

I often get this question, "How does working at a bookshop change your writing?" The answer is, I don't think it does. Being a published writer and working at a bookshop changes how you sell books, I think. If you farm the meat and butcher the meat, you'll sell the meat differently. [Laughs] You have an understanding of what goes into the books. I felt very strongly that the way to sell books was to curate a small collection and hand-sell them. There are three of us at Review: Roz, who started it who's now moved to Ireland, Katia, who's the manager now and who's brilliant, and me. We've all got very different tastes and interests. Roz likes art and architecture, a lot of Irish writing. I'm quite Antipodean. Katia is quite into sociology and psychology. Between us, we have a broad range and we're able to give genuine recommendations and hand sell stuff. If someone asks, why should I read this? We say, because it's amazing and I say so -- now get out! [Laughs] The way to do it is to have confidence in your product, so we only get in the books that we really really love and we don't pay attention to discounting.

Are you good at summing up and hand-selling your own books?

Actually, no -- I'm awful. [Laughs] It's this weird problem of trying to sum it up in less than a sentence. When you've got everything that's gone into the book, everything you've deleted, everything you've ever thought about the book in your head, it's very difficult to nail it. I'm probably the worst person with my own books. But it certainly makes me aware of what goes into books. Publishers are amazing creatures and the amount of people involved amazed me. It's ludicrous how little we value it. Amazon making the prices so unbelievably low that suddenly no one will pay more for a book than they would a beer. One of the things we do at the shop, unless we're doing a promotion for an event, we don't discount. We want to bring the value back to literature. I quite strongly feel than seven years of my life is worth 7 pounds 99. [Laughs]

I don't know what the literary scene is like in the UK, but here in the United State,s often when people write about the rural parts of the country, the books are seen as regional oddities rather than serious literature.

That's interesting. Definitely, people believe that London is the epicenter of literary interest, but then there's also such a history of all the big old writers -- the canon -- being interested in rural landscapes. Because literature in the UK is an older thing, I guess that could have something to do with it. The countryside here is kind of revered. I think there's huge snobbishness in the literary world but I think they apply it to everything. [Laughs] But I know what you mean. I think where cities are concerned, it is firmly believed that London is the only place that has any literary merit.

I have to ask about your next novel, because I have many friends who won't forgive me if I don't.

I'm working on another novel, and it's all set in England, so far -- and Scotland. It started life as thinking about my grandmother, the most archetypal English upper class woman, who I found really frightening as a child. Also, really cuttingly funny. And very unhappy. She was a gin alcoholic for most of her life. She just had one of those lives which is so sad and dull, I think she even described it as completely comfortable, but totally boring. I think part of the reason was because she was incredibly intelligent and never did anything with her brain because you didn't encourage your daughter to do anything much other than marry, so that's what she did. There's obviously a lot more to her than I ever saw, and that's what got me thinking about writing an alternative life for her, really. There's a book coming out to celebrate Charlotte Bronte's bicentennial called "Reader, I Married Him" and I have a short story in that which is the tone of the what I'm working on now. It's 1950s grimness. English "Mad Men" -- so, "Boring Men." [Laughs]

Evie Wyld and Joe Sumner will be in conversation with Kristen Radtke at Barnes and Noble Upper West Side in New York City on May 25 at 7 pm.