Nearly a dozen Image Comics creators crowded the stage on Sunday at Emerald City Comicon for a panel titled "Something For Everyone." In attendance at the panel, which purposefully highlighted the different genres that all of the various Image creators represent, were Kelly Sue DeConnick (writer, "Bitch Planet," "Pretty Deadly"), Megan Levens (artist, "Madame Frankenstein"), Jeff Lemire (writer, "Descender"), Kurt Busiek (writer, "The Autumnlands: Tooth & Claw"), Joe Keatinge (writer, "Shutter," "Tech Jacket"), Landry Walker (writer, "Danger Club"), Jay Faerber (writer, "Graveyard Shift," "Secret Identities") and Ivan Brandon (writer, "Drifter"). When moderator David Brothers announced that the whole panel would be Q&A, the line quickly filled up. The panel kicked off with a question about self-editing, specifically regarding what one does with old ideas that don't really work and how creators evolve their ideas over time.

"When I get to a point in the natural evolution of the story process and an idea no longer works, I don't like it anymore," said Landry.

Ivan Brandon said that he found the constant change and revision to his ideas to be just part of the order of things. "What you imagine and what usually gets published is so drastically different that you really have no choice but to go with it," he said. "Your story will be no part of what you imagine."

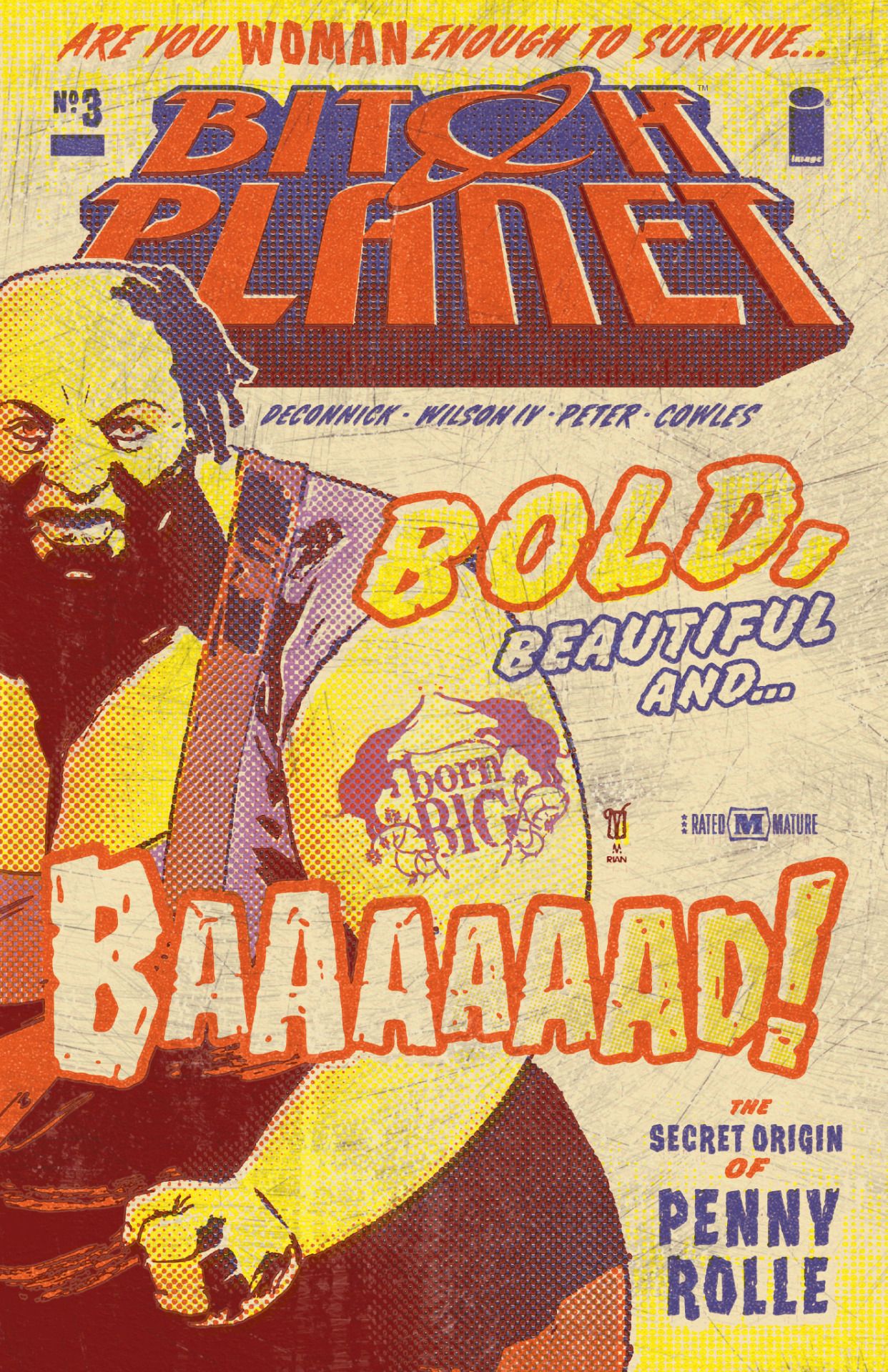

Kelly Sue DeConnick's "Bitch Planet" Breaks Barriers & Faces

Other writers remained much more attached to their old ideas. "You don't need to abandon ideas, you just need to put them back on the shelf," said Busiek. "I'm constantly doing stories built on some idea that I wanted to use fifteen, twenty years ago." Busiek singled out an unannounced Image story that he originally conceived of for "Avengers Forever." "Ideas that you like are never done," he said. "You don't have to let go."

DeConnick also hangs on to old ideas, whether or not she ever lets them see the light of day. "I have a file on my desktop that's labeled 'morgue,'" said DeConnick. "I don't have that experience where if an idea doesn't work I don't love it anymore. It usually has to be pried from my hands... Somehow having that file so I never have to actually hit 'delete' helps me."

A question about editorial oversight and involvement at Image Comics led to a discussion about control in creator-owned comics -- specifically whether or not some content was too out there -- and, surprisingly, paper stock.

"Anything that Image publishes, we want it to be in the creator's voice," said Brothers, who edits "Wytches," "The Fade Out" and "Lazarus" for Image. "We're down for whatever."

The writers bore out Brothers' comments by recounting editors saying yes to titles they thought were maybe too outlandish. Brandon, when pitching his sci-fi series "Drifter," compared it to doing drugs with robots and said that he got a reply of, "I'd like to do drugs with some robots." Likewise, DeConnick recalled a response from an editor that read, "I would very much like to publish something called 'Bitch Planet.'"

"So there's not a lot of censorship at Image?" asked an audience member.

"Have you seen my title?" replied DeConnick.

The panelists emphasized that creator control also meant giving attention to the details of how the comic was presented, all the way down to the quality of paper stock -- an issue which Brothers emphasized was not trivial. "Paperstock counts. The wrong kind can detract from the comic," he said, and talked briefly about how paper stock can affect how different sorts of inks hold to the page and how colors register or bleed during printing. Also, the current media market has affected what was once a cheap form of paper stock. "I don't know if you guys know this, but newsprint is super-expensive because no one uses it now."

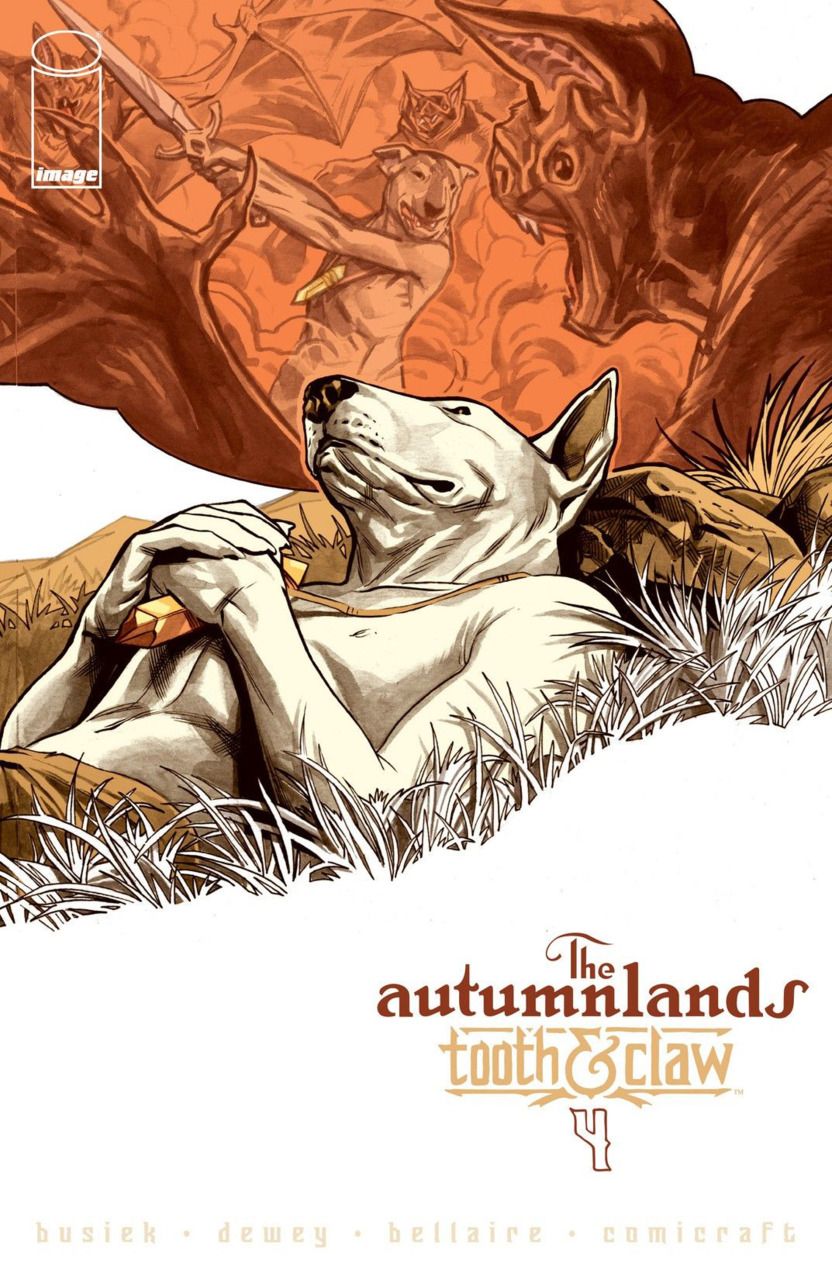

5-STAR REVIEW: Busiek & Dewey's "Tooth & Claw" #1

The panel then discussed the process of scripting comics, with DeConnick commenting on the different methods writers use to create scripts. "The really cool thing about comics scripting as opposed to any other scripting is that the styles are as various as the creators," said DeConnick. "Literally every person on this stage has a different scripting style. For instance, I don't number dialogue when I first turn it in, because I consider it rough draft dialogue." DeConnick also gave some advice to aspiring writers, saying, "If there's a comic you love, try to reverse-engineer the script."

"Start out with the focus of the panel," said Busiek. "Everything else is secondary." Busiek also talked about Alan Moore's scripts, which he admired but found too long. "Alan Moore was a guy who'd write a forty-page script for an eight-page story," said Busiek. "And he was the only guy whose scripts I couldn't read... The artists who worked on his scripts literally went over them with multiple highlighters to say 'this is visual, this is metaphor.'"

Brandon characterized scripting to writing a play, saying, "The artist is the one who's going to perform."

A panel-goer asked how much the reader was considered during the writing process. "No offense, but not at all," answered Busiek. "I want to do stories that I want to read... I don't know what the audience wants. I can't predict it."

The last question for the panel involved how writers avoid cliches, tropes, and common stereotypes.

"We talked about that," said Faerber, who's currently writing the space Western "Copperhead" with artist Scott Godlewski, "What are the cliches, the archetypes, the classic Western tropes, and how do we subvert them and play with expectations?"

Busiek was more sanguine about the writer's relationship to tropes. "We have a character who's subverting audience expectations about a mighty hero, and other characters' expectations of what a mighty hero is," he said, referring to his fantasy series "The Autumnlands: Tooth and Claw". "But I'm sure we're fulfilling other tropes in all kinds of ways... I don't think you can ever fully get away from tropes... but if you're telling a good story and you're telling an honest story... it doesn't matter... Make the characters feel real in what they do. [That] matters more than whether they fit some pattern."