On Friday afternoon at Emerald City Comicon in Seattle, some of comic's most stylized artists, including Rob Guillory, Erik Larsen, Kazu Kibuishi, and Klaus Janson, sat down to reveal their thoughts on realism in comics -- and why they think it has no place.

Moderator Gregg Schigiel opened the panel by explaining exactly how the unusually titled panel would flow. "The idea of it is to talk about the things in comics that are not realistic, because it feels like the trend in comics is to be quote unquote realistic. I say quote unquote realistic because the fact of the matter is Batman is neither realistic nor relatable in any way. He's a billionaire who's the greatest human in the world -- so we're going to celebrate costumes where you can't see the seams, thought balloons and weird panel shapes. All the unrealistic things that make comics awesome."

The panelists were then given a proper introduction, beginning with legendary inker and illustrator Klaus Janson. Janson's first professional inks were on "Black Panther" and he currently teaches at the School of Visual Arts.

"When you draw and you ink, you're not trying to be create a realistic image. You're trying to create an artistic image," Schigiel said of Janson's style. "You're trying to provide an interpretation of reality through your color theory and all that. You're not recreating reality, you're making comics."

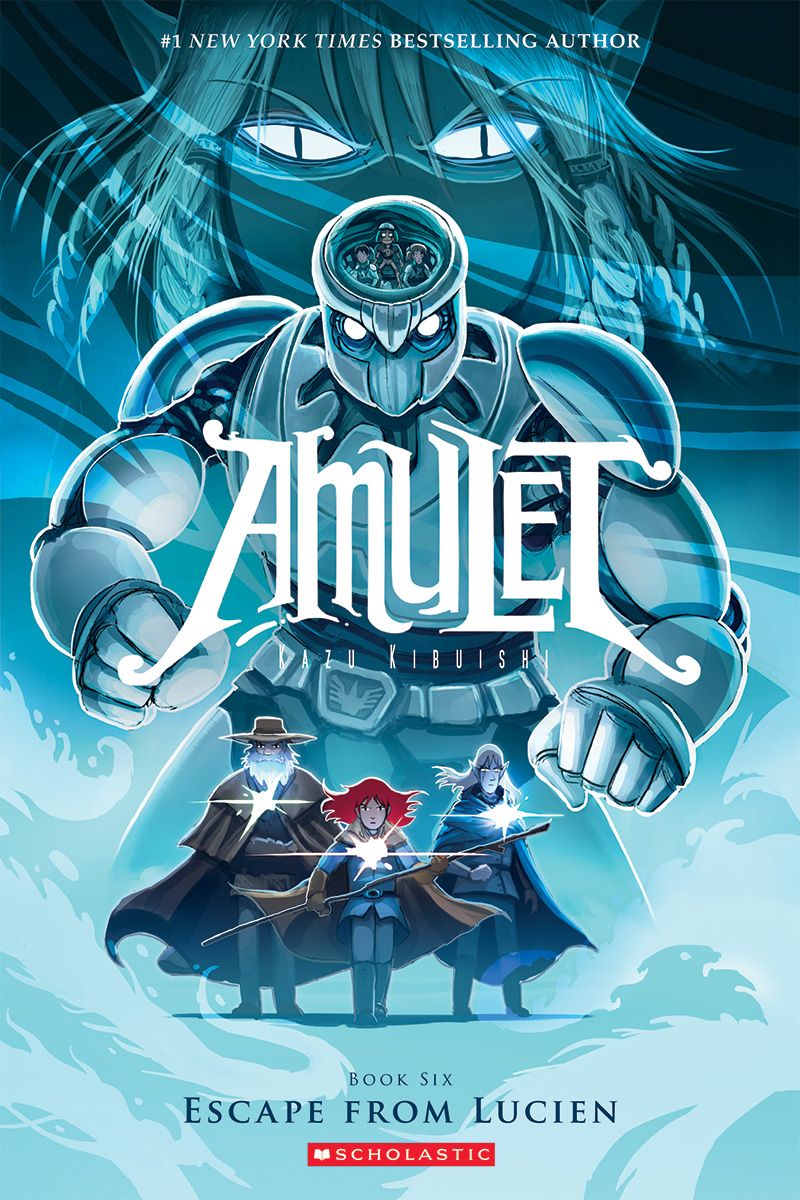

Next up was Kazu Kibuishi, writer and artist of the popular children's graphic novel series' "Amulet" and "Flight," whose work Schigiel described as "full of robots and talking animals and fantastic places," but also "emotionally relatable and grounded."

"I tell people that the only thing that's truly relatable in my work is the emotions," said Kibuishi.

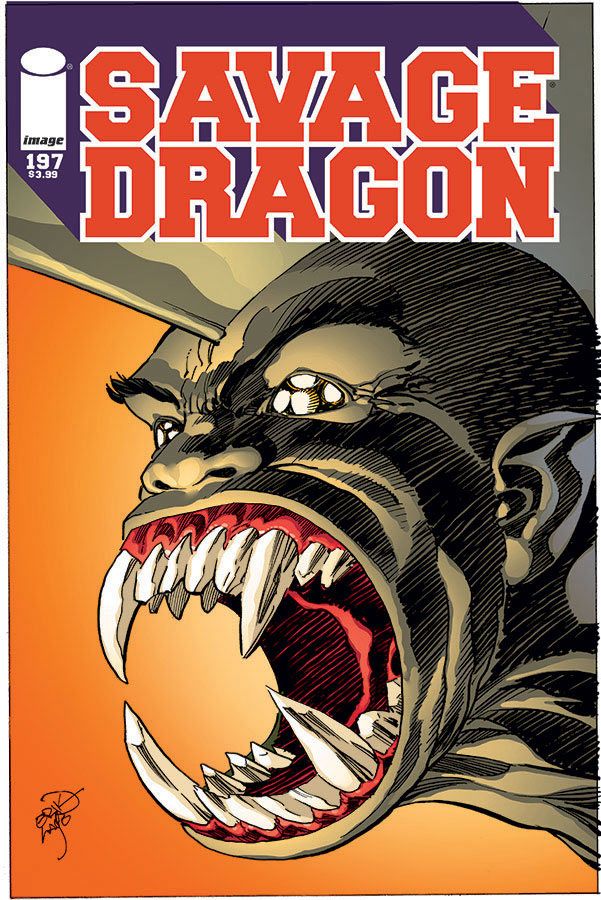

Though "Savage Dragon" creator and Image Comics co-founder Erik Larsen needed little introduction, Schigel offered one that provided even greater context for his role on the panel. "He's writing, drawing and inking a series that is far from realistic. He is doing modern Jack Kirby. He is blowing it out of the water and doing bold, ballsy superhero comics which not a lot of people do anymore."

Finally, Schigiel introduced "Chew" artist Rob Guillory to the crowd, and opened up the discussion by laying out what he sees as a problem with modern comics. "The tendency tends to be towards photo realistic rendering of art, realistic backgrounds, places looking like places, and you guys [on the panel] don't do that."

"I think the key term is believability," Kibuishi added. "So whatever you can do to make whatever it is you're creating believable, whether it's fiction or nonfiction."

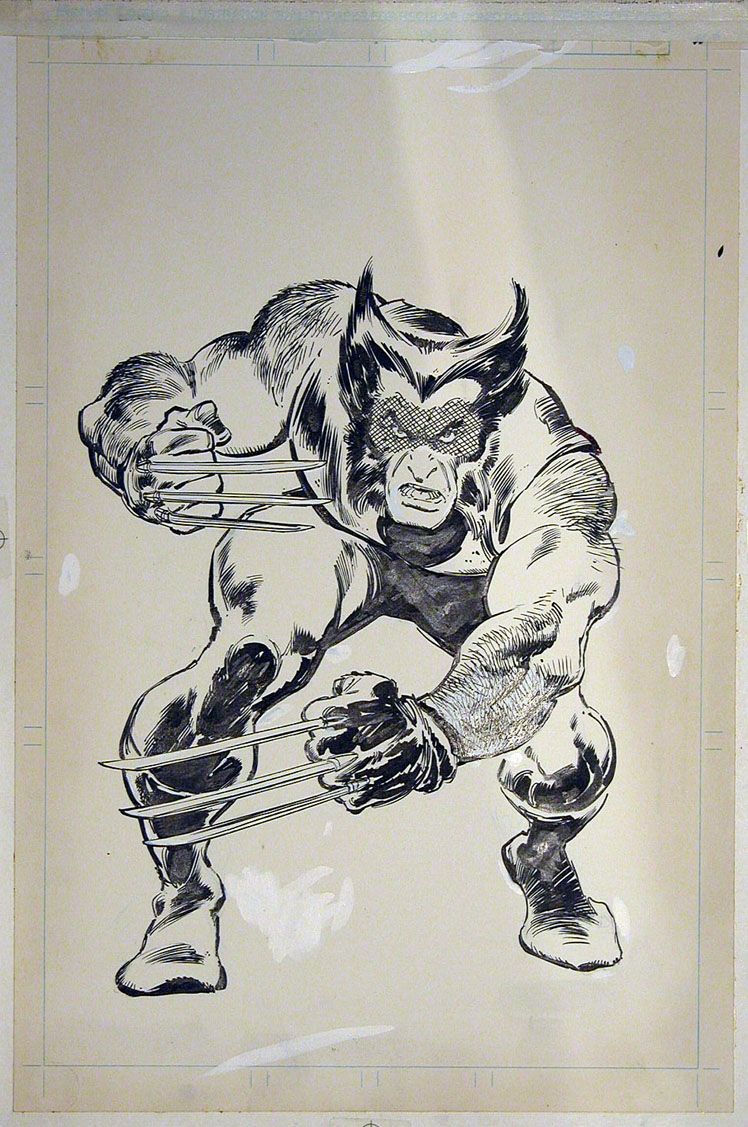

"When [the plot of] 'Chew' was announced there was people who were like 'Oh that's ridiculous!' But that's what comics are all about. Comics are all about unreality," said Guillory. "You look at a guy like Wolverine. He's a Canadian midget who's hairy and has knives that come out of his hands. And he's like the biggest guy in comics! Comics are all about accepting a reality and once you accept that reality it's all fair game. Once people understood that there's this comic called 'Chew' where people have food powers in a food-related world, the second people accepted that, it just went nuts."

Asked about working on "realistic" books like "The Dark Knight Returns" and "Daredevil," Janson said, "Once you create a world that's convincing and stays within its established boundaries you're good to go. The problem I have with reality-based art -- and I consider myself a cartoonist -- is I'm not a Xerox machine, I'm not a photographer. I stay away from mimicking reality. I can replicate it and play with it, but I'm not interested in mimicking reality. That's boring. I see reality every day. I see too much of it quite frankly. I want to see art that is channeled through someone's point of view."

Kibuishi described his own approach to realism when it comes to his characters' appearances. "My main characters are very simple. They're almost happy faces that travel through these super ornate lands," Kibuishi said. "I always point people back to 'Understanding Comics' by Scott McCloud and he actually pretty much nailed it, this idea going back to relatability. When you see a more rendered face you think of them as the other. When you see one that's simplified you start thinking of them as yourself. Because on their faces their emotions are clear but who they are isn't as clear. You apply yourself to it."

The "Amulet" cartoonist compared this technique to Miyazaki and Disney films which also feature detailed backgrounds against simplistically designed protagonists.

Janson liked Kibuishi's approach and mentiooned Bryan Hitch's use of Samuel L. Jackson as a reference model in "The Ultimates." "Listen, I'm a big fan of Bryan Hitch. What he does is quite an accomplishment. 'The Ultimates' is just amazing. But it took me out of the story [when Samuel L. Jackson showed up]. Janson pointed to a classic cartoon strip as an example of why realism isn't even necessary in comics. "Charles Schultz never drew three dimensions in his life. You'll never see Snoopy's dog house from an angle. It's always flat. And yet we completely buy 'Peanuts.' Nobody ever says, 'Oh this isn't real. It isn't three-dimensional, there's something wrong with this.'"

Larsen added, "Once you turn Snoopy's doghouse you realize it comes to a pitch, so there's no place for him to actually lie. It doesn't work!"

"The people who draw realistically, and we know who they are, bore me. I find that to be ultimately boring and incredibly uninteresting and I think that's one of the big drawbacks to drawing in a photorealistic style," Janson said. "It is boring. The figures are stiff. You're limited entirely to your reference and you can't go beyond your reference. And oftentimes your reference is completely inadequate. You're not pulling things out of your imagination. I just find that work to be incredibly shallow, empty and boring."

Janson then riffed on realism when it came to his coloring. He said, "I remember somebody today brought up a 'Punisher' cover, one of my favorite covers from that book, that had him in the water and there was black zipatone in the background and the cover was all yellow. I mean just all of it was yellow. I don't know if they'd let us do something like that today. The idea of it was it was visually catching and it had some electricity to it. The problem with color realism is that everything looks the same. If we were all doing photorealism we'd all be doing work that looked the same. And how boring would that be?"

Larsen said, "Just look around the room right now. Everything is in high-def and everything is fully rendered. When you're doing a comic book you don't want somebody to be focusing on a fork next to a plate in the background. That's not your primary concern. So if I just take that whole background and color it blue and just focus on these two guys having this intense conversation and just color the shit out of those guys, then you'll be focusing on the stuff that's actually important in the panel instead of being distracted by minutiae."

Kibuishi responded to a comment by Janson that very few comic book artists today can write, draw, ink and color their own comics. "I will say there is a generation of artists that can do those things really, really well but a lot of them don't work in comics," Kibuishi said. "It's because they're getting paid very well in animation and video games. They're going where the jobs are. That's what's happened in the last ten or twenty years."

The topic moved towards the tendency for modern superheroes to have "realistic" costumes, as well. "They can't pull of Mister Miracle's costume in a real movie. He's pulling cloth over his face and it's adhering to everything and his eyes are showing through. You can't make material do that," Larsen said. "It doesn't function that way in the real world. Instead of comics doing what they can't do and them trying to catch up with us, we're going, 'Oh wouldn't it be cool if you could see where Wolverine's costume is stitched together? It'd be really awesome if there was a seam right in the middle of his forehead!'"

Janson recalled a relevant story involving the artwork of "Marvels" and "Kingdom Come" artist Alex Ross. "I remember going a couple of years ago to an exhibit by Alex Ross in New York. So I'm walking around with a friend and I'm shaking my head just thinking, 'I don't get this. I don't get what all the excitement is.' And my friend said something which I'll never forget which was very, very astute. He turned to me and said it's all about the fact that Alex is putting wrinkles in the costumes. And in that moment I got it," Janson said. "I got exactly what Alex Ross was doing. And that's exactly what Erik was talking about. And that stuff bores the crap out of me. I'm just not interested."

Guillory thinks the problem is comics trying to be something they're not. "There's certain comic artists which try to be more cinematic, which is fine," said Guillory. "But I think comics have the strength of being comics. We're not movies. We're just comics."

Larsen pointed to one of the most critically acclaimed comic books of all time as the source of the problem. "I think it's fine if people do realistic comics," said Larsen. "I just think there's room for so much more so it shouldn't be 'let's just do this.' That was the problem with the sons and daughters of 'Watchmen.'"

Not all realistic comics actually look, realistic, however. Such is the case with the award-winning talking animal book "Maus," which deals with the Holocaust. "One of the most realistic comics I've ever read is 'Maus.' It's autobiographical, it's emotional, it's heart wrenching. The lead characters are animals telling a human story. Art Spiegelman uses every tool comics are capable of, art style changes, iconography, all these things," Schigiel said. "That's for me a high water mark of comics. When someone takes a very personal, real story and tells it in a comic book way."

Kibuishi then revealed that "Amulet" might not be as close to over as fans think. "I just finished 'Amulet' [volume] six. It'll be out in the Fall. I'm going into the last book in the contract with the idea that it will be the last one. But I thought the second one would be the last one when I started that one. Right now I told them I was going to go for seven books and that's what my contract was for but I'm not sure if it's going to land right there because I have a lot of kids coming up to me and asking to extend it," Kibuishi said. "I had a nice conversation with ['Usagi Yojimbo' creator] Stan Sakai just now about that idea -- obviously I'm not going to say it in public, I guess, but I have had conversations with my editor about where we're going to go."

Finally, Larsen reaffirmed his commitment to he book he's drawn for nearly two decades. "There is no end for 'Savage Dragon.' It is going to go on until I die and that will be the last issue."