Long ago in a bygone era, there was a unique style of Dungeons & Dragons adventure: a chaotic thrill ride known as the funhouse dungeon. These older style modules may not be the norm anymore, but they still have their place. Sometimes you just need to find some wacky trouble with your playgroup and you don't care who needs to lose a limb in the sphere of annihilation to get it. Let's go through the ups and downs of one of D&D's most puzzling styles of play.

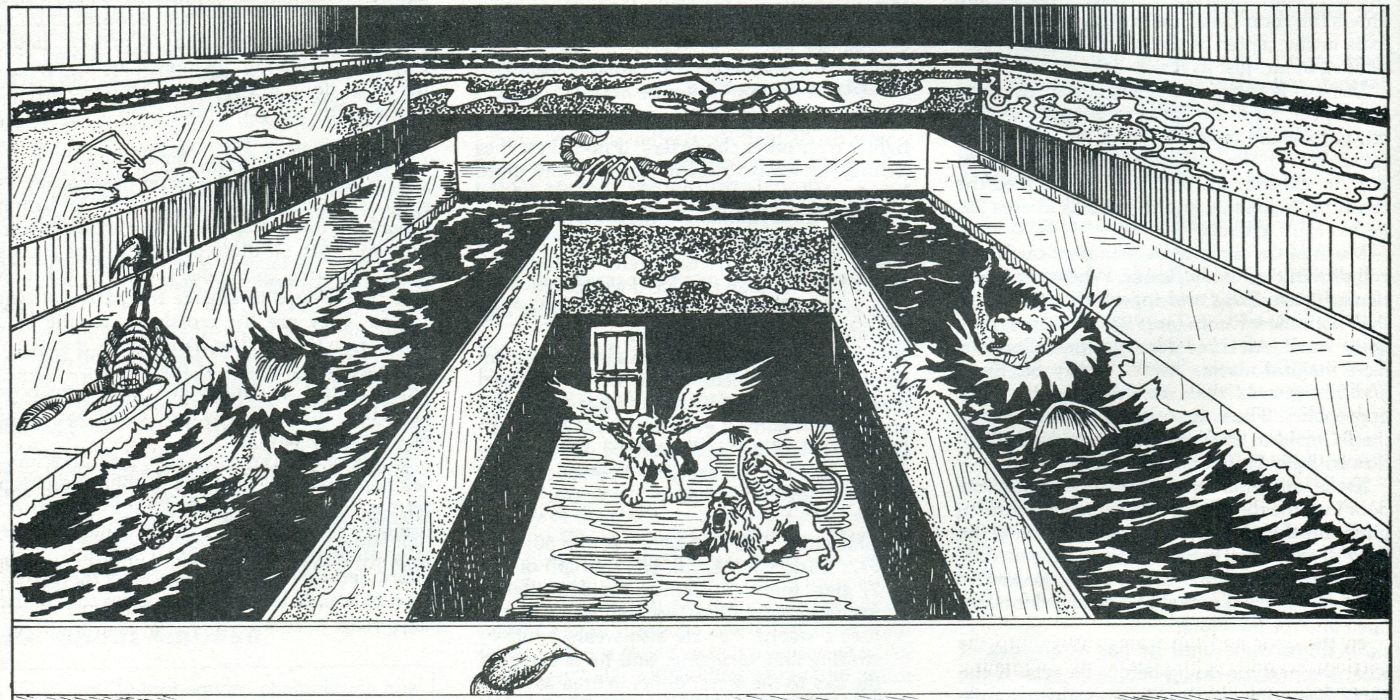

At their core, funhouse dungeons are self-contained series of tests, usually incorporating loads of puzzles and traps. No particular attention is paid to logical consistency -- one room might be a hall of swinging blades only for the next to feature a reversed gravity puzzle with the next featuring a riddling monster. The story behind them tends to be limited, and next to no time is spent explaining how or why their bizarre creations function. Add to this a general tone of levity and often intentional prankish humor, and you have classic dungeon modules like White Plume Mountain, republished for 5E in 2017's Tales from the Yawning Portal.

In White Plume Mountain a mad wizard has stolen a series of artifacts from the lords of the land and hidden them in an equally mad gauntlet, complete with a taunting poem riddle to guide the players through. If White Plume Mountain feels like someone wrote down a list of every cool idea they had for different dungeons and then mashed them all together, it's because that is exactly what it is. The module was written by Lawrence Schick in 1979 as a submission to then D&D publisher TSR. Not only did the editors at TSR love the submission, but they also published it without letting Lawrence do any revisions, resulting in the strange brew that would come to define the funhouse dungeon.

In modern games, narrative and roleplaying take a more central than they were in the early years when modules like White Plume Mountain were written. In the era of Critical Role and Game of Thrones, epic fantasy stories aren't just an advantage. They are the expectation. It can be hard to put those expectations on the back-burner or away entirely in order to engage with a funhouse. Suspension of disbelief needs to come fast and silliness should be on the table.

Funhouses can be hard to tie into a regular campaign because they are just so weird, and the narrative motivation for funhouses can be pretty nonexistent. The thing is, that doesn't really matter. Which brings us to the first thing to remember about enjoying the funhouse -- it's an experience to be savored, not necessarily an epic tale to be told. A funhouse dungeon can be something your playgroup remembers for years because of the wild things that occurred within them, not why those things happened in the first place.

Funhouse dungeons can be arbitrary and even cruel. It is brutal when a player character steps inside the wrong square and they become transformed, disfigured or dead. Sliding helplessly through a frictionless room in White Plume Mountain directly into a blade-pit with super tetanus (yes really) isn't the best feeling either, so consider avoiding bringing cherished, long-term characters into the funhouse.

If your players enjoy challenging their characters and themselves, a funhouse dungeon is a unique way to test a group. Under most circumstances in D&D, the challenges are practically solved by the characters being roleplayed. In puzzle and riddle-heavy funhouse dungeons, however, it is the players themselves who are challenged. While this sometimes requires hand-waving or house-ruling for exceptionally intelligent players, for the most part, there is no character sheet based mechanical way to solve most funhouse problems.

Funhouses also challenge a group by rewarding teamwork. These dungeons can feel like escape rooms with time on the clock and only the game master to give the team clues as they huddle around a handout and try to figure out a solution. This level of personal engagement can be slightly intimidating at first, but it is also exciting and rewarding in ways that solving problems entirely by dice roll is not.

Funhouses give game masters the freedom to excuse themselves from the burden of a heavy narrative and jump straight into the action. This makes them ideal for a single evening's entertainment, for new game masters and for players who just want to keep the plot simple. Character development will likely be minimal, and their motivation will probably only be to make it through and loot rooms, but playing a dungeon this way can still be satisfying.

Finally, the funhouse lets the game master completely unleash their creativity. Do you want to use a cluster of dissonant ideas for a single adventure? That's what funhouse dungeons were made for. Build the perfect Rube Goldberg machine trap, mash all your favorite Valve physics puzzles together or show players what all that gross Mind Flayer technology does. This the perfect chance for a GM to brainstorm something mind-bending, awe-inspiring or hilarious. Pitch it as a single night's entertainment and encourage players to create characters specifically for the funhouse, then impress them with something strange.

Funhouse dungeons might seem a little outdated compared to how most groups currently enjoy D&D. That said, these can be incredible and uniquely challenging RPG experiences that clever game masters will learn a lot from. Even if a game master incorporates only some of the weirdness of a module like White Plume Mountain, they will add a touch of entertaining chaos to their game and a unique off-the-wall challenge to their players.