I don't really need to waste words telling you guys how special comics are, and of the unique artistic alchemy that goes on in their creation and their reading, in which verbal and visual components fuse and synthesize, and the readers finish, almost animate the pages in his or her own imagination. You guys know all that; you read these things all the time.

What you may not think about as much, because I know I don't, is something that comics can have a lot of trouble dealing with: Sound. Aside from the rustling of the pages, there's no sound involved in reading comics, and the writers and artists have to get pretty inventive when it comes to trying to include sound in their comics narrative...at least if they want to do so effectively.

In Frank M. Young and David Lasky's The Carter Family: Don't Forget This Song, a comics biography of the massively influential early 20th-century music group, sound is obviously something that's rather important. Music is the thing that binds the main characters together; it's what first brought young Sara to the attention of her husband A.P. Carter, it's what they did with Sara's cousin Maybelle, it's what obsessed A.P. to the point that he neglected Sara, it's the legacy the family left behind, and it's the reason the book exists in the first place.

Perhaps the easiest way to put sounds into comics is to simply describe it in prose narration, using adjectives and comparisons to help the reader imagine the sounds for themselves the same way prose writers like novelists or newspaper reporters might. The problem with that approach, I think, is it's not necessarily a "comics" solution to the problem, and, in the production of great comics, doing-things-that-can-only-be-done-in-comics is a pretty important criteria.

Additionally, prose narration has fallen out of fashion over the decades, as comics readers and, especially, artists have become more sophisticated, and the crutch of paragraphs of prose per page is no longer needed to support anyone (Have you gone back and tried reading many Marvel Essential volumes, for example? And noticed how unnecessary so many of those boxes of words actually are, whether the writing in them is good or not?)

The traditional solution to sound in comics is, of course, onomatopoeia, the "BANG!" of a pistol and "SOCK!" and "POW!" of a punch, the "BOOM!" of an explosion and so on. This has long been the route superhero comics and the other popular genre comics of decades past—romance, western, horror, and so on — have gone. Sometimes onomatopoeia incorporated into the artwork can be very effective. I've always been impressed by Dough Moench's use of sound effects, as he's always come up with very specific collections of letters to evoke very specific sounds, like some sort of ingenious comics Foley artist.

These too seem to have fallen by the wayside, however, perhaps because of the long-lingering stigma of the 1960s Batman show that so many creators and readers have sought to escape in past decades, and perhaps simply because of the growing sophistication (and graying) of pop comics in general: Everyone's seen a glass window being shattered in a movie or TV show, so do we really need a "KRSSSSSSSSSSSHHHHH!" covering up part of the art? Gunshots, punches, explosions — if the art is working right, one need not see a sound effect to know what is happening, and the sounds won't be such unique ones that they need to be there.

There are certainly times when sound does need to be there, though, and watching comics artists seek out ways to use visuals to evoke an audio experience is always interesting and, when they do it quite well, exciting. The best recent example I can think of is James Stokoe's drawing of Godzilla's trademark cry in Godzilla: Half-Century War, in which the artist apparently used an oscilloscope to chart the rises and falls of the sound.

There's nothing so exotic as the roar of a 300-foot-tall, reawakened prehistoric monster in The Carter Family, of course, but there is obviously a whole lot of singing and instrument-playing. Being able to capture the exact sound isn't necessary to Young and Lasky's story, as it is about the lives of the A.P., Sarah and their extended family more than the particular sounds they created during their lifetimes, but there are multiple moments when the creators need to evoke the nature of their singing, or even the simple act of a person singing a song, which space and pacing would have made ten panels of someone sitting on a stool with their mouth open while drawings of cords and hand-written lyrics fill the background of these panels.

There are a lot of panels of lyrics being sung, usually in italics and surrounded by familiar cartoon musical notes within wigglier dialogue balloons, and there are several panels of filled with clouds of musical notes to evoke Maybelle playing guitar or A.P. playing the fiddle. And there are also lots of example of traditional, sound effects integrated into the art — the "BLAM!" and "SCREECH!" of a car tire blowing out or the "CRRRRRRRRASH!" of a cedar tree being felled and so on.

Here are a few of their creative solutions.

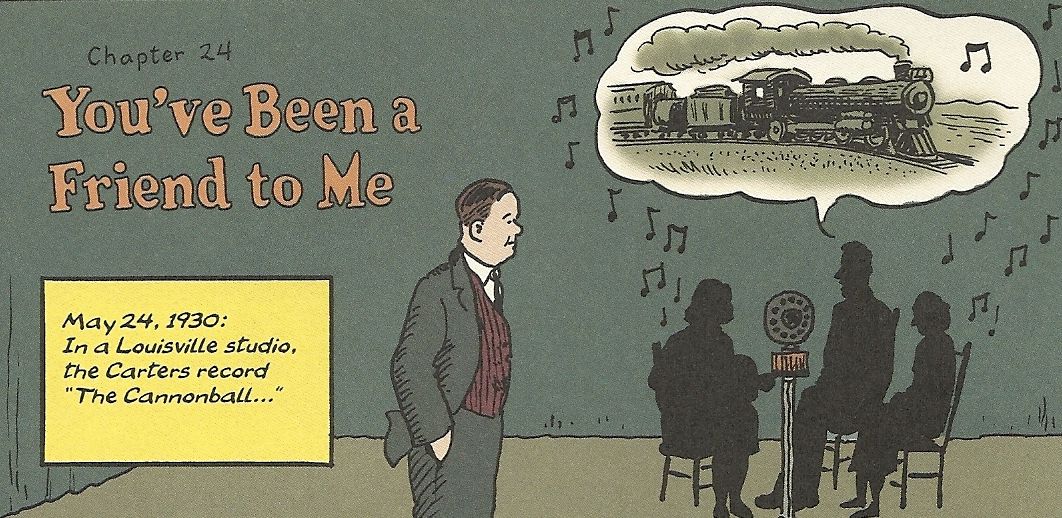

Esley Riddle, a friend and collaborator that A.P. meets while scouring the countryside for songs, teaches him "Cannonball," a song about a train, and its singing is depicted by filling a wiggly dialogue bubble with drawings of the events within the song. Here are panels of Riddle and then the Carter Family playing it:

Obviously it doesn't communicate the sound of the song, but it does communicate the content of the song, at least in terms of its subject matter, if not its lyrics.

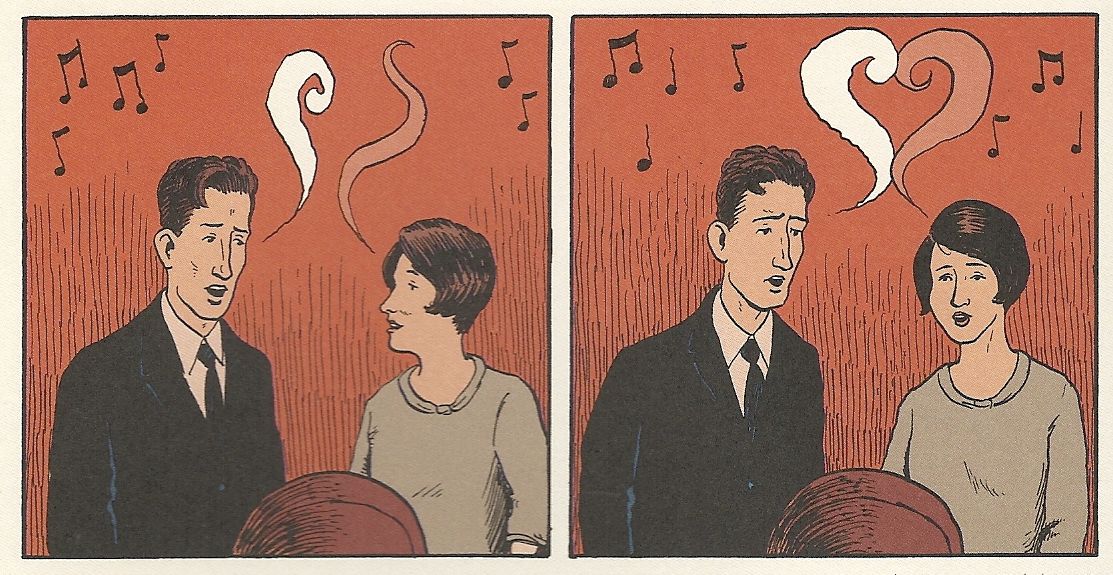

Here is a page from early in the story, in which a young A.P. meets a few of his rival suitors for Sara's affections, and they bully him into singing for them. He does, and Sara joins him:

What song were they singing? What exactly did it sound like? The page doesn't say; it does demonstrate quite effectively how beautiful it was (look how the beauty of flower of their mingled voices eclipses the actual flowers the man in the tie is holding!), and how it is made of their voices joining together.

A similar, if less elaborate, instance occurs later on between the same characters, when the Carter Family gets into a studio:

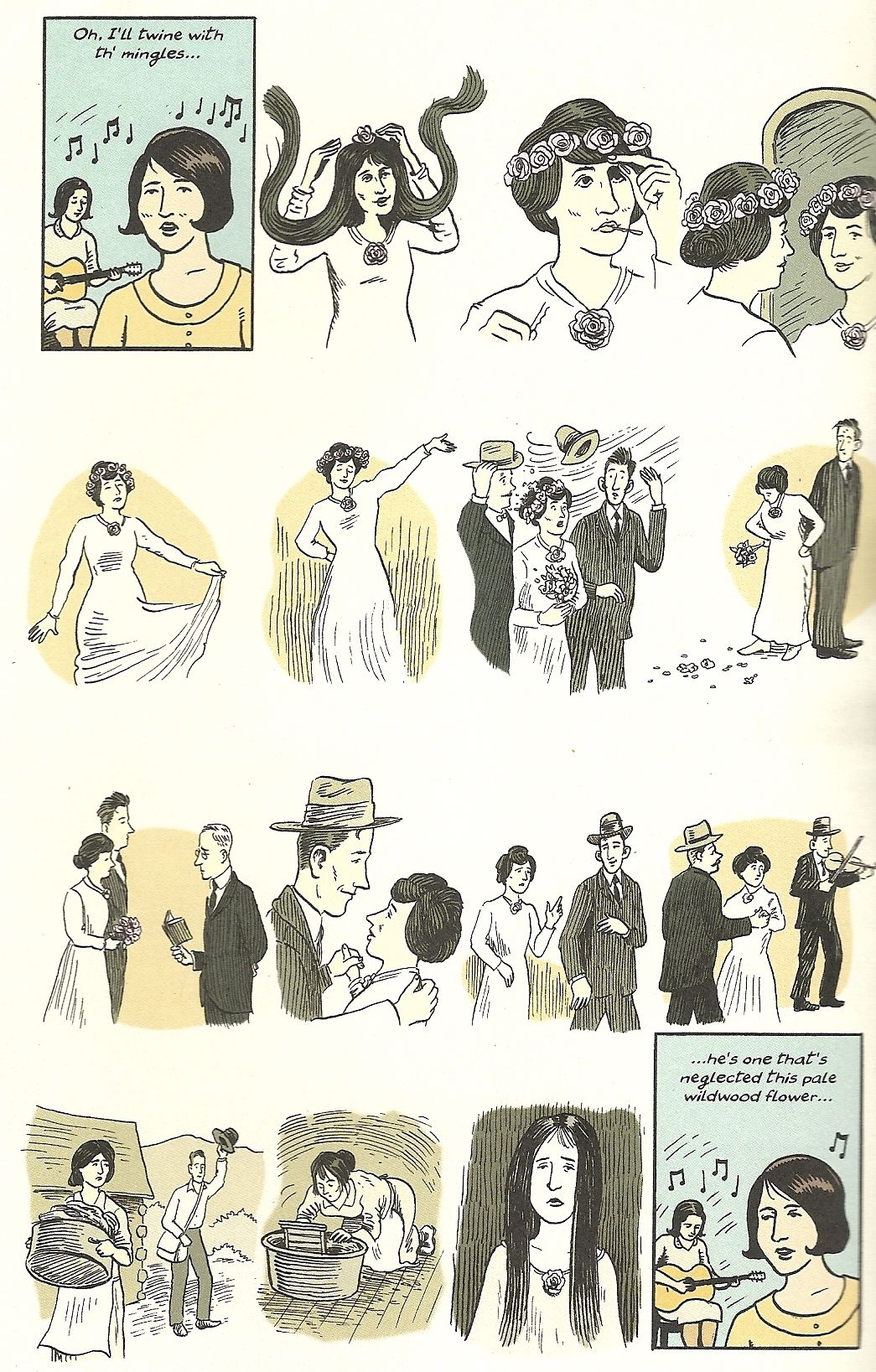

One final example. Here's Sara Carter singing "Wildwood Flower":

The song takes place outside of the borders of the comics narrative, we leave the panels all together when she starts signing, and only return when she's done, and the story of the song is shown without words or suggestion of sound, beyond what the ethereal quality of the art, and the way it differs from the art in the rest of the book, might suggest.

The Carter Family does come with a "Bonus Music CD" in the back of the book, with 11 tracks. A reader can therefore hear exactly what they sound like before, after or during the reading of the comic. But as interesting as it is to be able to hear, and match the characters' actual recorded voices to what one might have imagined they sounded like during reading, it's hardly necessary.

Lasky and Young do a fine job of communicating what's important about the characters' voices and music within the book, so fine that what is important about those aural elements is within the panels themselves. That makes the bonus disc just that—a bonus; nice to have, but hardly an integral part of the whole.