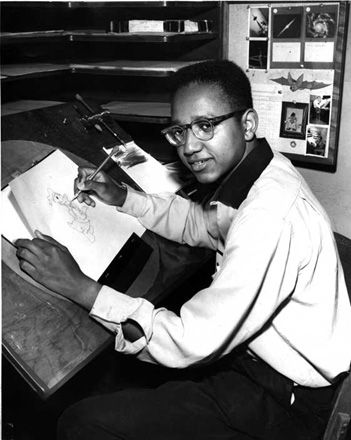

When animation history was being made, Floyd Norman was there.

Although he never consciously set out to blaze new trails or break racial barriers, a 21-year-old Norman in 1956 became the first animator hired by Walt Disney. As a clean-up artist, he contributed to some of the cornerstones of the studio’s towering legacy, including The Sword in the Stone, animated segments of Mary Poppins, various shorts and Sleeping Beauty, which has now spawned the live-action reimagining Maleficent.

Becoming a story artist with The Jungle Book, Norman ventured off on his own after Disney’s death, leading to a storied career in television animation as a layout artist (Josie and the Pussycats, The Smurfs, Super Friends and dozens more). He eventually returned to the studio, first as a writer of its characters’ comic books and then in the story department for the Disney Renaissance (Hunchback of Notre Dame, Mulan) and the rise of Pixar (Toy Story 2, Monsters Inc.).

Still active at age 78 as an animation consultant, Norman sat down to chat with a select group of journalists at the Disney Animation Research Library, where he reflected on his memories of Sleeping Beauty, the enduring impact of the film after its initial flop, and his own long and creatively fruitful association with the studio.

When and how did Sleeping Beauty first make its way to you? What was your first encounter?

Floyd Norman: I was invited to a screening back in 1956, I believe. They took us upstairs, and they had been working on Sleeping Beauty for a number of years. They didn't have much to show, and what they did have to show was only in pencil and in storyboard. But I do recall this scene in the castle before the King and Queen, where Maleficent appears with the crack of lightning and thunder, and there she is – and it's like “WOW!” That was quite a moment. So that made quite an impression on a young animation artist just getting started. And of course, the animator was Marc Davis, and he did just this beautiful job of bringing the evil fairy to life. That certainly made an impression on us.

What's been the long-term legacy of the movie amongst the animation community?

The film was a bit of a flop in its initial release in 1959, and I remember sitting on a train, reading Time magazine. The film was reviewed, and it was a scathing. The [critic] not only disliked the film, he hated the film. And sadly, the public did as well, and Sleeping Beauty did not do well on its initial release. Imagine how we felt as animation artists who had worked long and hard on that film and to have it open so poorly. But, you know, it's the movie business. Sometimes films find an audience, and sometimes, they don't. Good thing we had a leader like Walt Disney, because it didn't seem to bother Walt one bit. Maybe Walt had been through so many failures, another failure was no big deal. And I do remember Walt saying, “We're going to do 101 Dalmatians next.” He didn't dwell on the past. He didn't even deal with the present that much; it was the future that was important to Walt. He just said, “We're doing Dalmatians next – Sleeping Beauty, we did the best we could. They don't like it? What can you do?” And so we just moved on.

Angelina Jolie Casts New Light on "Maleficent's" Darkness

So how did it become an icon of Disney animation?

I think what happens sometimes is that audiences find a film. And I think what happened was, with Sleeping Beauty, decades later audiences found the film and said, “Hey, this is a well-made film. This is a beautiful film. This is a unique film, and we'll never see the like of this again.” Sleeping Beauty was a product of its time. It was a handmade, hand-crafted product. We had no technology back in the ‘50s. We didn't have the photocopy process. We didn't have digital paint. We didn't have the computer. Everything that was done on that film was sketched on paper, inked with a pen, painted with a brush -- truly a motion picture hand-crafted, made by hand. And Sleeping Beauty was the end of an era. There would never again be a film like that made at the Disney studio.

Which characters did you work on?

The three good fairies, Flora, Fauna and Merryweather. I learned to love them. You know, us boys, we want to do the gutsy stuff – we want to do the Prince or the Horse, so for us, it was like, “Oh, we've got to draw these little old ladies? These little round, little old ladies?” They were cute, you know. They were like little grandmothers. They bounced around, and they were kind of cute. It was like drawing grandmothers for two and a half years, but we did, and we made the best of it. As a matter of fact, the three fairies really carry the film, because we don't see that much of Aurora. We don't see that much of Prince Phillip. And the two kings appear in a couple of scenes. But really, the film is carried by those three good fairies.

What did Walt Disney think of the film, and Maleficent in particular?

I really can't answer that question, because back then I didn't have access to Walt Disney. Keep in mind there was only one area Walt focused his attention on – truly focused his attention – and that was story. In those days, I was not in the story department. I was in animation, so in animation, you rarely saw Walt Disney, if at all. Walt would always focus his attention upstairs in the story department, so that's why I have no idea how he felt about the characters in the film because we never had a chance to hear from him. I'm sure his story guys did. They probably heard from him on a regular basis. Probably not enough, because part of the problem with the film was that Walt's attention was divided: He was doing television, short films, feature films; he opened the theme park in Anaheim. He was just too busy, and so he didn't spend enough time on the film. I think it would have been a better film had Walt been able to devote more time to the storytelling, but he was just being pulled in too many directions back at that time.

“Maleficent” Director Robert Stromberg Hopes to Conjure Big-Screen Worlds

A special alchemy existed with Maleficent and her animator, Marc Davis. Can you talk about that experience in general, when the animator just really has something special going on with the character they’re assigned?

Yeah, Marc was a gifted animator, a really talented guy. He was a great artist in many ways anyway: He was a painter, he could draw beautifully, so he was a well rounded artist. And so when he embraced a character, he took that character over, and I think that's why Maleficent is so special as a character. As a matter of fact, we want to see more of her, not less. It's almost as though we wished we had a film about Maleficent. Well, thankfully, now we do! [Laughs] But there was something very special about the way Marc handled the character in those few scenes we have of her. And Marc’s team – he was followed by Dale Barnhart, Fernando Arce, Ruben Apodaca, Bob Longo – who did the final clean up drawings on the evil fairy. But she was a special character, and Marc Davis brought her to life using the wonderful voice of Eleanor Audley, who had done work for Disney before: She was the Wicked Stepmother in Cinderella, so we all knew that voice. There's something about Eleanor's voice that is just so cold. I mean, it's an elegant voice – this is an elegant person, but a very scary and dangerous person. So I think with what Eleanor oddly brought to the character vocally and what Davis brought through his drawing and animation, we just have a truly compelling character. It's just a shame we don't have a better stage to put her on because she's truly a great character.

You weren't crazy about the fairies, but who are some favorite characters that you've worked on?

Sadly, I never earned the title of Disney animator. I like to tell that story that I came here to become an animator. Now, that didn't mean that I didn't animate, because I did animate on occasion – but I never garnered the title of animator. What happened in 1966, while I was on that path to become a Disney animator, Walt Disney decided I was a better storyteller than an animator, so I found myself suddenly in the story department. Not my choice, by the way! It was not my decision. Back in those days, Walt decided for you. You didn't have to worry about deciding for yourself. Walt knew what was best. So he said, “Not an animator – Story man.” So that's how I became a story man.

Anyone ever challenge Walt on decisions like that?

Nobody challenged Walt on anything [laughs]. No, if Walt made a decision, even if that decision concerned you – like for instance, I didn't want to be a story man. I didn't think I knew how to tell stories. But Walt Disney said, “You're now a story man,” so you just say “Yes, sir,” and you do it. You do the job given to you, and there are no ...

Was he right?

You'd have to ask the audiences who watched films I worked on. Here's what happened: When The Jungle Book was finally released in 1967, audiences loved it. It was a hit film, and to date people still talk about that film – they come up to me and say “You worked on The Jungle Book? That's my favorite Disney film!” And all I can say is, “Yeah.” You don't know. You do the job that's given to you. You do the best you can and you hope people like it, but there's no guarantee. I've been lucky that I worked on a lot of good films, films where I felt the story came together, where things just worked and I've been real happy with the motion picture. How much I contributed to that? You don't have any real way of knowing, because a motion picture is a collaboration. When I write a book, or when I was in publishing, I was writing stories, I could say those stories were mine because I wrote them. But when you write a movie, you're making a film with an army. So you're never sure how much of it is yours or how much of it is the rest of those hundreds of people out there, because we're all making a movie together. But what it did do for me is it got me over my fear of writing because when Walt said, “Start doing story,” I just started doing it. And I said, “Well, it's not so bad after all. Maybe I can write.” So years later, when Cal Howard, an old story guy here at Disney, said, “You ought to join our publishing department and start writing stuff for us,” instead of saying, “Oh, I don't know how to write,” I just said, “OK.” Came in and started writing: “Write a Mickey story.” “Mickey story coming up!” “Donald story.” “So you want a Donald story – yeah, yeah!” “Got a Goofy story? Yeah!” I just started writing, and I found out that stories would just flow out of me, and I didn't have to work that hard. It wasn't that difficult to write a Disney story. I just felt like I was so infused with Disney, I just sort of knew what to write. And I remember one of our top editors was complaining about he'd been handed a lot of manuscripts. He said, “These aren't Disney stories.” He was unhappy because the stuff he got wasn't Disney. And I thought, “Well, how hard could it be?” And so I looked and I read some of these things, and I said, “You're right – they're not Disney stories.” There's just something about Disney that I just got. I just knew deep down inside what I had to do. And I think that's why when I was working on Jungle Book when Walt Disney was unhappy with Bill Peet had done and he said, “I want this film rewritten.” I just knew what to do because I knew what Walt wanted. He didn't have to articulate it. I just knew what a Disney film because I had been watching Disney film since I was a child. I had been reading Disney books since I was a child. I knew what a Disney story was.

What is a Disney story?

A Disney story has to have compelling characters, and it's got to resonate with the audience and the reader. You've got to connect with the characters, and there's always a sense of optimism and hope, even though you might be going through dark and dire times. There's ultimately, a happy ending. Sounds kind of corny, but there's a lot of happiness and magic in a Disney story. Now, these things are kind of intangible when you're trying to pull all these ingredients together, but to me, when you do it enough, you know when it's there, and you know when it's lacking. And so when I went up to Pixar to work, I just knew I had to bring that same kind of storytelling with me, because that's what resonates with the audience. And if it's not there, you feel it. You feel when it's missing. You feel when it's not connecting. And there have been some Pixar films that haven't connected for me because they'll miss that. To me, those things are critical for a Disney motion picture.

What was the key lesson from Walt, himself, a philosophy you've used your entire career?

Walt always emphasized the characters, first and foremost. One of the things we, as writers, were complaining about on The Jungle Book – I think you can apply this to Sleeping Beauty as well – was plot development, and Walt said – these were his words – “You guys worry too much about the story.” And so I found that interesting, because you think of Disney and Disney storytelling: “Well, isn't the story everything?” And Walt Disney said, “No!” He actually told us, “You guys worry too much about the stories. Story's not a problem.” He says, “Make me love the characters. If I love the characters, then the story will take care of itself.” So I think that's the key lesson there.

Was it ever a concern that Maleficent would be too scary for kids?

No, no. As a matter of fact, I think Walt liked scaring kids. I mean, really. When I saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, I was a little kid, that film terrified me. I went home and had nightmares after seeing Snow White. So I don't think Walt thought Maleficent was too scary. Probably, he wanted her to be even scarier, if that was possible. I think he liked scary stuff. I think he felt kids should be scared [laughs]. He wasn't making a kiddie film by any means. No. He saw them as family films, but he never saw them as children's films, as babysitters for kids.

You were working from fairy tales, from Kipling, from other source material. Now work you did is serving as inspiration for films like Maleficent, for a whole new set of stories being told. Is that a cool experience?

Yeah, it is. It's nice to know that the work that you've done – and in my case, sometimes work I've done 50 years ago – is still around, that people still watch it, they still talk about it. It's nice to know that the work you've done lives on. That's a pretty good thing. I'm not unhappy about that!

Disney’s Maleficent opens Friday nationwide.