Despite cartoonist Bill Watterson ending Calvin and Hobbes in 1995 after a 10-year run, and never licensing the characters for animation or merchandise – no, not even for stickers of Calvin peeing on vehicle logos – it remains one of the most beloved and enduring comic strips in the history of the medium.

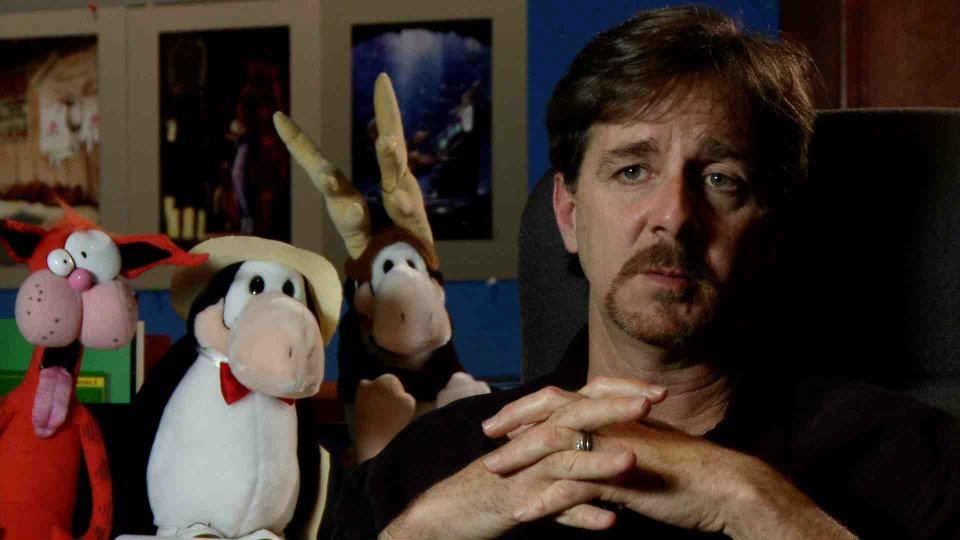

Twenty-eight years after Watterson launched his saga of a boy and his stuffed tiger, director Joel Allen Schroeder has created the documentary Dear Mr. Watterson to pay tribute to the duo’s misadventures, and to take a closer look at the strip’s impact on fans and fellow artists alike.

Schroeder recently sat down with Spinoff Online in Los Angeles to discuss Dear Mr. Watterson and how he peered inside a cultural phenomenon that seems determined not to be one. In addition to talking about his own preconceptions, Schroeder highlighted the value of the elusive Watterson’s absence from his film, and reveals the piece of merchandise he would want if there were licensing for Calvin and Hobbes: rocket ship underpants.

Spinoff Online: This was obviously something very personal to you. How did you make the transition from taking an anecdotal look at individuals’ love for Calvin and Hobbes to examining the strip’s larger cultural impact?

Joel Allen Schroeder: I knew that I clearly needed to set up that there is an impact. Actually, I know one review I read about the film is that they wanted to hear from fans even more to sort of further prove the wide impact. But I knew we needed some impact from fans, and I felt that we needed a thread from myself. I knew I would be in the film as some sort of narrator, but then it became a little more clear with the urging of our producers, that I did need to be in it a little bit myself. So when fans come to watch the movie, hopefully right away they are introduced to me as someone very much like them, and that the film is coming from a place of love. But I did want to go beyond that; we didn’t want it to just be a film that’s all about, “Here’s a film that’s all about how much we love Calvin and Hobbes.” I really felt like there were reasons why the strip, beyond being so well drawn and well written, that it does have the legacy that it has, and I wanted to dig into those. [To examine] Watterson’s decision to not license and not allow merchandising, and his decision to retire the strip after 10 years. I think those are integral to why it has had the impact it’s had. Like if you imagine another scenario where there’s Calvin and Hobbes plush dolls and Happy Meals, would we think about it in the same way? I don’t think it would take away from how well-drawn or -written the strip was, but it might change our perceptions of it.

How many of those reasons that the strip resonated did you sort of know when you started the film, and how many emerged from interviews with your subjects?

I think I had a pretty good inkling of them – I knew going in that the decision to license definitely had a big impact, and letting the strip end when he did, I felt like that was a good decision that had played a role. But as you start to talk to people about it, sometimes someone has a way of [pinpointing things]. Like Stephan Pastis, his original answer to one question was nearly seven minutes long, and I remember reviewing it and going, people are going to think I’m crazy for putting this entire clip in the movie. But he comes at the licensing and merchandising from such a perfect perspective, being an attorney, being a cartoonist, being a huge fan of Charles Schulz and Peanuts, and if that sort of analysis came from me, it doesn’t mean a whole lot, but coming from Pastis it means a whole lot. But people helped connect the dots, and you’re looking for evidence to help support the hypotheses that you have, and once you have all of these conversations all of these things came together.

I’m sure you knew early on that you would not be talking to Bill Watterson, but what to you is gained by his absence?

One thing is, let’s say he was available. But it’s hard to know what he thinks of the strip. Like, I’m so close to my film that it can be difficult for me to view it objectively, and I think in the same way, it may be difficult for him to view Calvin and Hobbes objectively. So him not being there doesn’t muddy the waters. I think that a film with Bill Watterson would be a very different film. Like you said, I went into it knowing he being a part of it was not likely, but had we gotten an indication we would be able to include him and involve him, we would have pursued that. But one of the reasons we didn’t was because I didn’t want the story to be about “these filmmakers tried to track down Bill Watterson,” even if the movie was not at all about that process. With any topic, you can make a lot of different films, and this film happens to be one I don’t think relies on him being on-camera and interviewed. We did try to include him – there’s words from Bill Watterson, and I feel like I found very relevant quotes that helped to keep his voice in the film even though we don’t see him.

One of the ideas the film explores is that Calvin and Hobbes was one of the last great pop-culture hallmarks before the Internet changed the way we experience these phenomena. How quickly did that emerge as something you wanted to discuss or examine during the process of making the documentary?

One of the questions I would ask cartoonists was, “Could there ever be another Calvin and Hobbes?” And I kind of got mixed answers – Jan Eliot, who does Stone Soup, her answer was, well yeah, of course. There’s no reason why someone as talented as Bill Watterson can’t create a comic strip that connects with readers. And then on the other side of that, Berke Breathed expressed the idea that there will never be another Calvin and Hobbes because no one will ever reach an audience the way that Calvin and Hobbes did. I am optimistic that talented artists will continue to make wonderful work, but in the way things have changed in the last 15, 20 years and continue to change, I don’t think you will have someone who has the talent that Watterson had and have their daily comic strip in front of millions of eyeballs around the world. So that level of great personal impact, multiplied to that level, I don’t think you will ever have. I feel like that section came from me trying to agree with Jan Eliot’s idea, but [suggesting] it won’t reach that breadth again. We knew that the shrinking of comic and newspapers dying off played into it, but I guess on the flip side, it wasn’t necessarily wondering why there hasn’t been another Calvin and Hobbes, but this idea of we are so lucky we got Calvin and Hobbes when we did, because it was the right time. It was the man with the right talents, who had such a respect for comics as an art medium. So I recognized that these are some of the things that went into why Calvin and Hobbes had an impact, and how is that different now.

What insights about Calvin and Hobbes did you glean from making this documentary that you had never though of before? Or maybe what was the most important discovery you made for yourself, whether or not it was significant to the film?

I don’t know that I can explain this well, but Watterson is known as this recluse – which is a word I don’t really like. It just feels kind of dirty, like we’re saying something’s wrong with the man. And everything I learned about Watterson in this process has given me the impression that he is a guy who prefers his privacy – he’s not a strange guy. He has his family and friends, neighbors and the people he interacts with, and the fact that he doesn’t want to show up on TMZ, that’s pretty normal. And after doing this, I feel like he does have a sense of the impact that Calvin and Hobbes had, but I don’t know if it means anything to him. I guess what I’m getting at is ultimately, I feel like I think he’s very content in life, if that makes sense. Because sometimes early on I was worried, like with the process of making this comic strip and then having to end it, is he a happy guy? He did this great, wonderful thing for us – did it make him an unhappy man? And I don’t think that is the case.

A big part of the film deals with the absence of merchandising, but if there was one collectible or piece of merchandise you could have for Calvin and Hobbes, what would it be?

The stuff that I think would kind of be cool would be stuff that’s referenced slightly, like rocket ship underpants or Chocolate Frosted Sugar Bombs cereal. It wouldn’t have to have Calvin and Hobbes on it, but they would be like these strange little inside jokes that no one would know.

Dear Mr. Watterson premieres today in theaters and On Demand.