In 2016, DC Comics announced four modern reimaginings of classic Hanna-Barbera properties. Scooby Apocalypse moved Scooby and the gang to a post-apocalyptic setting (They dropped the ball not calling it Scooby Doomsday). Wacky Raceland was now a bizarre but incredibly dull Mad Max riff. Future Quest saw various Hanna-Barbera superhero and action series such as Space Ghost, Birdman and Johnny Quest cross paths for a single epic adventure in what probably comes closest to capturing the “classic” Hanna-Barbera spirit.

RELATED: DC’s The Flintstones Is a Surprisingly Dark — and Honest — Satire

But by far the strongest of the four titles was The Flintstones. In twelve issues, writer Mark Russell and artist Steve Pugh have created a series that is both one of the sharpest social satires to come out in recent years, and one of the most moving explorations of the human condition that you’ll ever read. That’s right, one of the best comics of 2016 and 2017 was about the modern Stone Age family.

Make 'Em Laugh

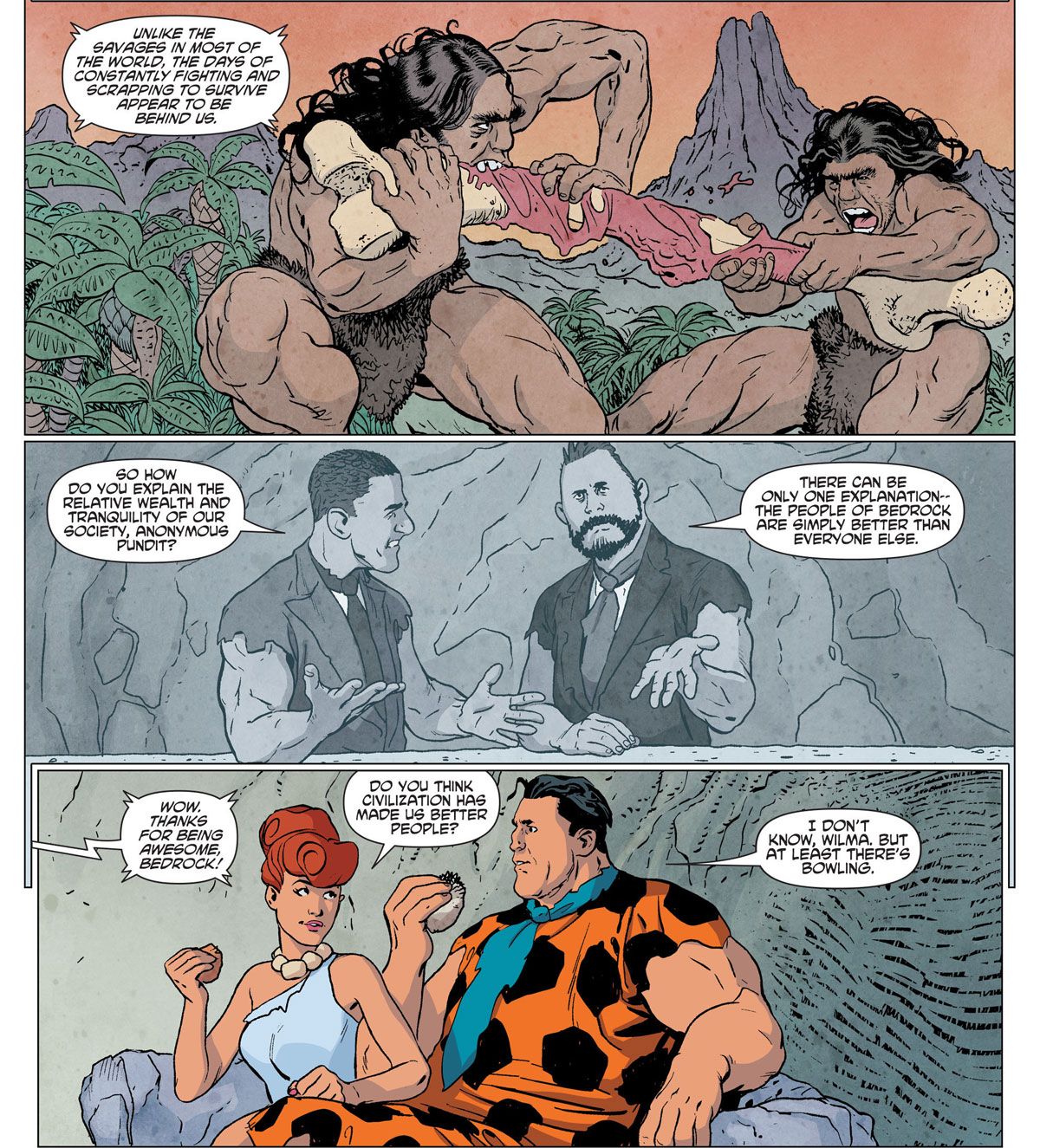

Satire is tricky. Go too critical, and people can read it as an attack on their beliefs; go too broad, and you end up with cliché, unfunny jokes (the closest they come to this are the hipsters in Issue #11). Overall, however, Russell and Pugh manage to hit that sweet spot, offering incredibly biting social commentary filtered through some hilarious jokes.

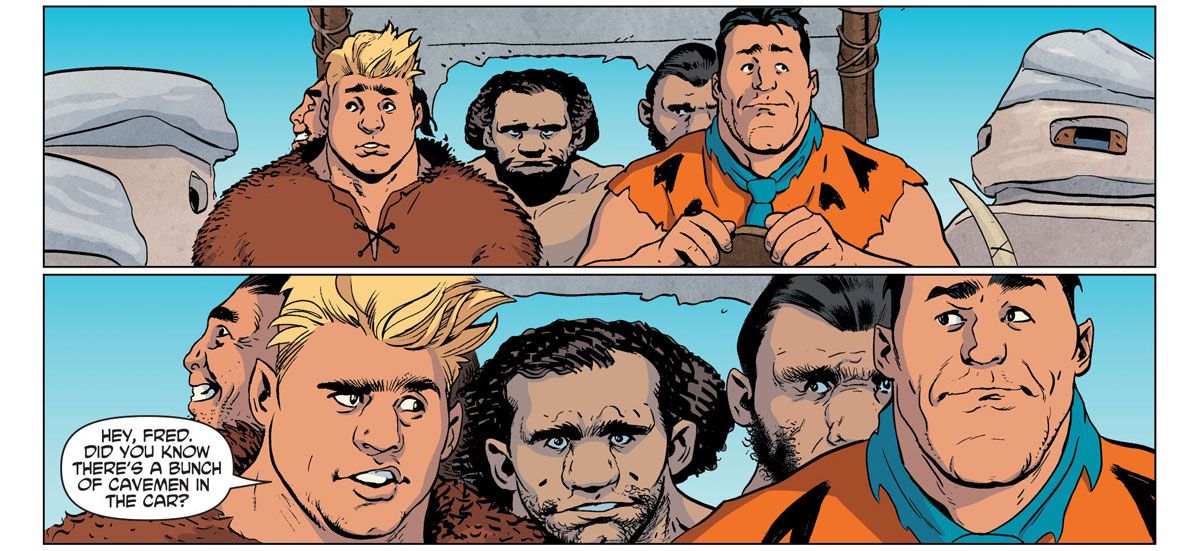

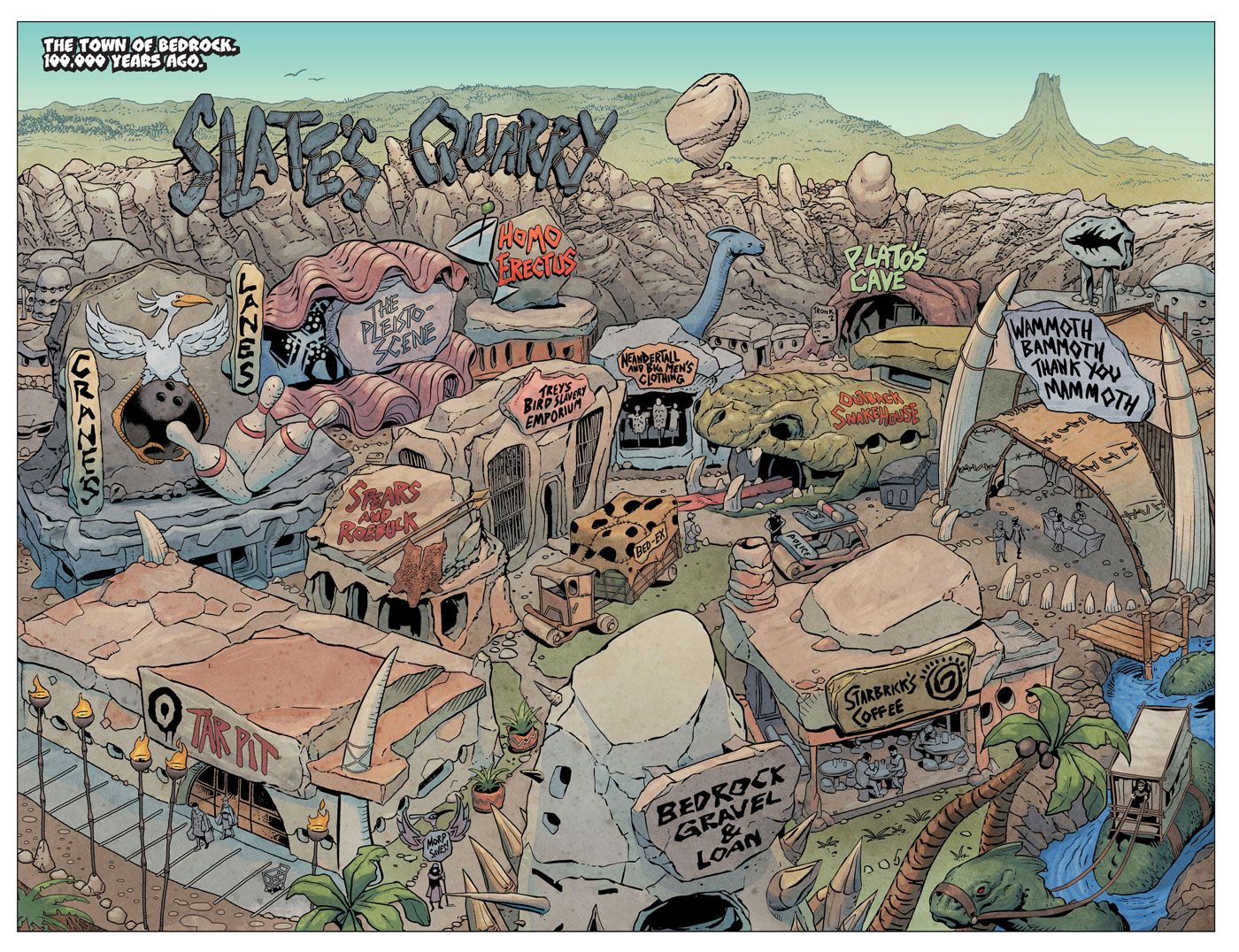

As far as collaboration go, Pugh’s art style and Russell’s writing go hand-in-hand. For every joke or goofy pun Russell makes, Pugh backs it up with some amazing cartooning. His characters have an amazing cartoon elasticity to them, especially their faces. Pugh jams as many amazing backgrounds jokes in as possible. The movie theatre is called “Plato’s Cave”, characters eat the “Outback Snakehouse” and Pebbles is constantly seen reading “Cannibalism: The Unknown Deal” – a riff on Ayn Rand’s “Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal.” Artist Rick Leonardi fills in for one issue, and while he doesn’t do a bad job, Pugh’s absence is definitely felt.

The Big Issues

There’s a difference between making something “adult” and “mature,” and that difference is where a lot of reimaginings fall flat. Jamming your book with sex and violence makes it more adult, but if those concepts are just there just for the sake of it, it comes across as immature. This distinction is important, because Russell goes to some dark places with The Flintstones, but he approaches them with measured maturity.

Russell rewrites Fred and Barney as PTSD-suffering veterans of a war where they unknowingly committed genocide. The Tree People they fight are presented as bloodthirsty savages who want destroy Bedrock’s way of life, but the reality is they’re a peaceful race that were only defending themselves. They’re wiped out because they had the bad luck of living on the granite base that Bedrock was to be built on. The scene where Fred realizes what they’ve done when he discovers a child’s burnt toy is an absolutely brutal and heart-breaking reveal.

The second half of the series focuses on the rise of Bedrock’s new mayor, Clod the Destroyer. It’s through his macho-bravado and by tapping into the xenophobic insecurities of the town’s people he’s voted in, promising solutions for non-existent problems. Clod closes down the children’s hospital to buy new dinosaur war armor, playing into the town’s fear of the unknown to justify it like his father, Mordok the Destroyer, did with the Tree People. Clod declares war on the Lizard People because they eat a Bedrock citizen’s ferns. He uses the town’s taxes to enforce a surveillance state where the patrolling drones eat innocents. It’s not hard to miss which modern world leader Russell and Pugh are satirizing.

For all the fun they poke at modern society, Russell and Pugh don't pull any punches when it comes to shining a spotlight on civilization’s faults. Capitalism and mindless consumerism can give you things you think you want, but ultimately we don’t need. We’re a shallow society, willing to place more faith in things than actual people. By far, the most “human” characters aren’t actually the people of Bedrock, but the sentient animals that serve as the town’s various household appliances.

The Meaning Of Life

Issue 2 introduced Bedrock’s constantly evolving religion. First there was Morp, a normal stork who the original nomads of Bedrock viewed as a divine messenger. Next was Peaches, the elephant vacuum cleaner. And then came Gerald, the invisible god. Russell spends most of the series presenting the Church of Gerald as a bunch of goofballs who are making everything up as they go along. The Reverend introduces the concept of Hell to keep people coming to church, because if your actions don’t have consequences then why be bothered with following Gerald at all?

Professor Sargon, Bedrock’s leading scientific mind, concludes that “loneliness” is the invisible force that binds the universe together and sets everything in motion. That’s why we make friends; that’s why we get married; that’s why we create art. When Fred’s boss Mr. Slate is faced with his own mortality, he realizes his greatest fear is dying alone and being remembered by no one.

RELATED: DC’s The Flintstones Was the Most Socially Relevant Comic of 2016

In the final issue of the series, Pebbles asks the First Church of Gerald’s Reverend how he knows that Gerald is even real. The Reverend bluntly and honestly answers (with one of Pugh’s goofiest faces of the entire run) that he doesn’t.

“The truth is, we are all born incomplete into a universe not of our making. And we all need something to fill that void. To make us feel like we exist for a reason. For some people, that’s family. For others, it’s art”, he explains to Pebbles, “But some of us need Gerald to fill that void. To make our lives feel as though they’ve mattered. It’s okay if you don’t. Science is probably better at telling you what to believe. Religion is more about what you need to believe.”

It’s such a touching monologue, and yet again you can’t help but point out that it’s in a Flintstones comic, of all places. While the answers provided by science and religion might conflict with one other, they both provide a sense of structure and closure for people who need something to believe in. If you want to believe Gerald created everything, that’s fine. If you want to believe that the earth sits on a giant turtle's back that revolves around the sun, that’s fine too.

“In the end, I don’t think it really matters whether Gerald is real or not – so long as our need for him is real.”

The Pursuit Of Happiness

Mr. Slate, the richest man in Bedrock, considers himself the most important man in existence. His entire life revolves around making sure people will remember his name; the great irony is that in the modern era, our era, nobody remembers him. Instead, the nameless Neanderthal he goaded into fighting a mammoth is the only preserved member of Bedrock's community, and is assumed to be the leader of the city by modern-day historians.

Despite Slate’s overblown sense of self-importance, he does offer an important nugget of wisdom to Fred: “Men are only remembered for their accomplishments.” Unfortunately, Slate spent most of his life caring only about himself and his business, establishing himself in the ivory tower of Bedrock’s elite class. And yet, his message remains valid. It doesn’t matter who you are, it’s what you do that counts in the long run. While eulogizing the recently deceased Vacuum Cleaner (He was used to clean a movie theatre floor. ‘Nuff said), Bowling Ball concludes that “everything in our lives worth having is the product of others.” It’s a husband supporting his wife’s dreams of being an artist, a war veteran adopting an orphan, or a bowling bowl befriending a lonely vacuum cleaner. Crap can’t bring you happiness, but people can

Evolution

The Great Gazoo -- who in the original cartoon was a wisecracking alien that only Fred and Barney could see -- has been reinvented as a intergalactic Game Warden, whose job is to keep other extraterrestrial life forms from interfering with the natural progression of human evolution. Throughout his stay in Bedrock, he makes it pretty well known that he doesn’t care for the human race. Despite thinking humanity is overwhelmingly flawed and a danger to themselves, when the entire planet is faced with destruction he chooses to save them because, “Despite their shortcomings, they show great capacity for change.”

And that’s the overarching message of Russell and Pugh’s Flintstones: it’s easier to destroy than create, but you get nothing from destruction. The world can be a scary and lonely place, and it’s easy to judge others purely based on their beliefs or appearance – Russell and Pugh don’t back down when tackling how ugly humanity and so-called civilized life can be. People will straight up refuse to understand another’s way of life because it’s inconvenient to them. When discussing the newly created concept of marriage, one of Bedrock’s news anchors describes it as being “An immoral threat to our way of life… because it wasn’t around when I was kid!” But Russell and Pugh also remind us that we all have the capacity for kindness. It’s easy to destroy, but more worthwhile and valuable to understand.