Mimi Pond’s first full length graphic novel, Over Easy, was a semi-autobiographical chronicle of a young art student making ends meet by waitressing in late 1970s Oakland, surrounded by a wild cast of drug-addled wannabes, literary-minded underachievers, and working class joes. However, Over Easy -- which won a PEN Center USA Literary Award for Graphic Literature in 2014 -- was only half the story.

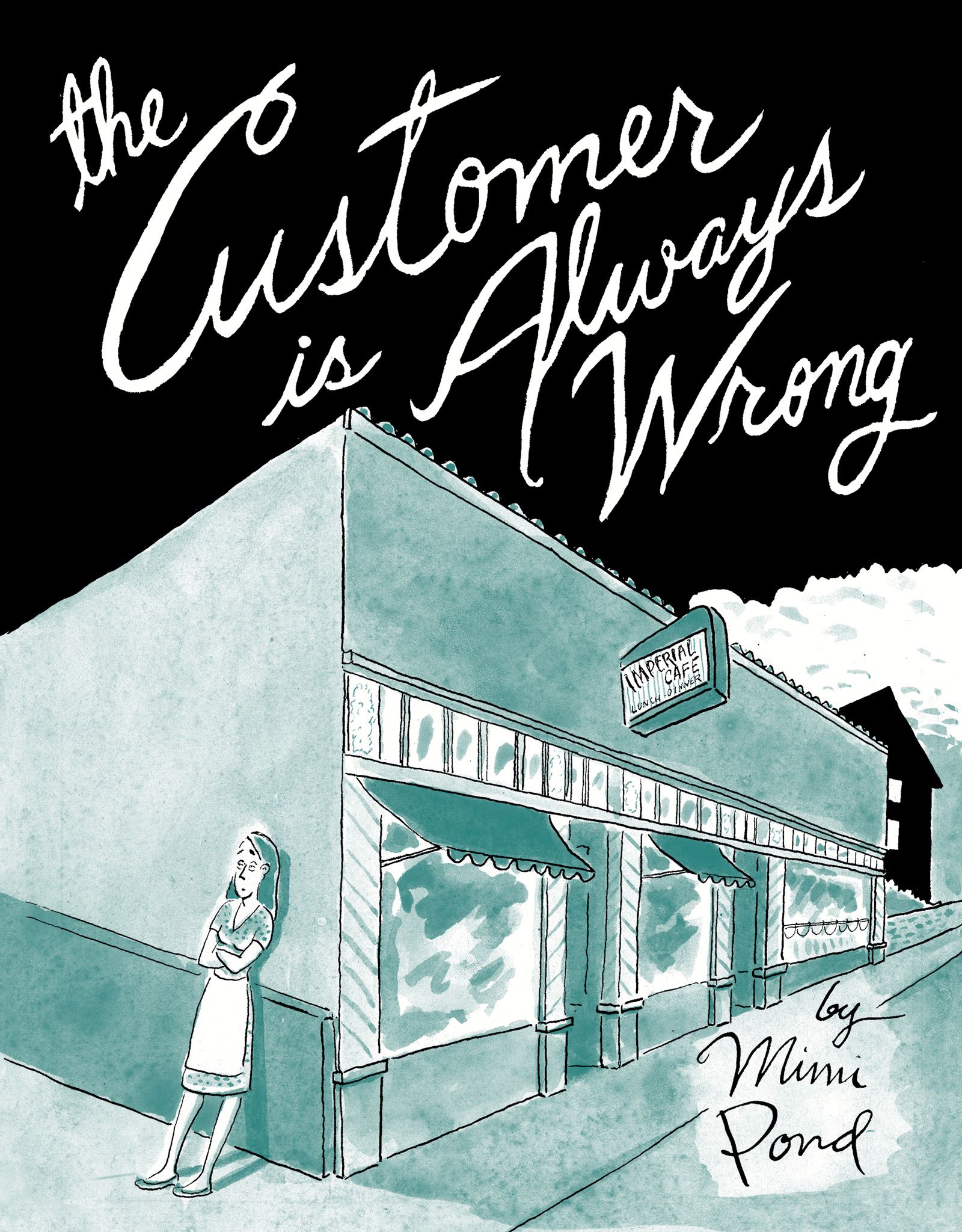

This August, Pond returns with the second installment of her fictional alter ego Madge’s time in diner purgatory. The Customer is Always Wrong, published by Drawn & Quarterly, follows Madge as she saves for her move to New York, where cartooning success awaits her. But before she can earn the money she needs, she’ll face drug dealers who mistake her for someone else, struggle through the aftermath of a lousy boyfriend, and cope with the gut punch of two deaths from her close-knit diner family -- all while bearing witness to an endless string of wild nights and self-destructive behaviors.

RELATED: Mimi Pond Takes the Acidic Nature of the 70s “Over Easy”

Pond (also known for writing the first full-length episode of The Simpsons) took some time to answer CBR's questions about The Customer is Always Wrong, explaining how the book is a biography of a time and place more than of a person, and talking about how much time these stories have needed for her to tell them.

CBR: You note that this is a fictionalized memoir, names changed, etc. I’m curious how much is fairly accurate to your life, because Madge has an extremely tumultuous sequence of events unfolding over a relatively short period of time. I thought I must nearly be done with the book, so much had happened -- and then I realized I was only a third of the way through!

Mimi Pond: I’ll just say it was, as they say, “inspired by true-life events.” It’s not so much that it was accurate to my personal life. There were episodes related to me by a number of people with whom I worked that I folded into this story. I didn’t want it to be a documentary-like story. I wanted to just capture the spirit of what that time and place felt like.

Madge experiences real physical and emotional trauma in this book, much more so than in Over Easy -- abortion, assault, deaths of several people close to her. Was it difficult to revisit those moments and reopen old emotional wounds?

It was difficult to revisit some of those moments. I did have an abortion, and a bad boyfriend, and that was pretty painful. I felt like it was important to express an experience many, many women have had -- having to undergo an abortion, first of all, and then, with an unsupportive partner. I also felt like it didn’t have to be the end of the world. It was just one of many decisions that I chose to make for myself, and at the time, no one passed judgement on me. I don’t know why our society has now decided they get to judge you. It’s no one’s business but your own.

Madge has a clear goal in throughout this book -- to make enough money to move to New York to pursue her art, which keeps her on task. Consequently, she often becomes more a witness than a participant in some of the wilder behavior around her. I was wondering if you feel these two books are more an accounting of that time and that place, seen through Madge’s eyes, even more so than being Madge’s personal journey?

Absolutely! I really wanted to express what it was like to be alive then, in the midst of a kind of moral swamp. There were a lot more gray areas we operated in. I felt like some of those gray areas -- like drug use -- should have been more black and white, and others -- gender identity and sex in general -- were not easily definable and made life a lot more interesting. In some ways women owned their sexuality more than they do now. There was no such thing as a “walk of shame.” You just slept with whoever you wanted to. There was a great deal more casual racism and sexism that simply went with the territory. You can’t time travel back there and tell them they were wrong. It’s just the way it was.

If anything I felt I had more of a voice as a woman working in that particular place, because “Lazlo” had a lot of respect for strong women. Later, in New York in the ‘80s, I remember trying to express my frustration with sexism at places like The National Lampoon, and simply being dismissed and labeled as a troublemaker. You didn’t have the power of the internet. You didn’t have millions of other people joining the conversation and supporting each other in shared experiences.

In Over Easy, Madge was excited to work at the restaurant, to “join the real world”. That novelty has worn off in The Customer is Always Wrong. Madge still recognizes the value of the stories unfolding around her -- was there a moment that made you realize it was time to start telling the stories you’d been living?

I knew from the very first day I worked in that restaurant that it was a story that I would one day have to tell. It just took me years to figure out exactly what that story was.

While both books are of a piece, Over Easy had a handful of storytelling experiments -- unusual layouts (words swirling in coffee cup, words shaped like a dress) and larger blocks of text -- that aren’t as prevalent in The Customer is Always Wrong. Did you notice your approach to the work evolving as you worked through two book-length projects, especially as compared to the shorter work you’ve mostly done in the past?

It felt like the intensity of the story was picking up and propelling everything. I didn’t want to stop to show off any fancy tricks, I just wanted the story to keep moving like a freight train.

Do you feel the experiences related in this book and Over Easy shaped your cartooning in any clear way?

I feel like I have developed a lot more discipline for my work! Doing short-form comics is very different than long-form ones, but I think I have learned to think much more visually and use visual shortcuts and not as many words.

The book ends with Madge, after waitressing for four years, moving to pursue cartooning. Were you supporting yourself with your artwork after that move? Are there more tales of the young, yet-to-be artist finding her way?

I was very fortunate when I moved to New York. I had a little nest egg that was almost gone when I had the opportunity to write and illustrate The Valley Girls' Guide to Life, which then became a best-seller. I worked a lot all through the ‘80s and did five humor books all together, along with comics and illustrations. I’m not sure about a book about New York in the ‘80s. I’m thinking about it!

After 30 years as a working cartoonist and illustrator, what moved you to pursue novel-length confessional memoirs?

Like I said, this story was lodged inside me and it wasn’t going to let me rest until I finished it. It has been inside me since 1978!

What’s next for you?

I have been doing comics for the newyorker.com recently. Those are really fun to do. The liberating thing about webcomics is there is no restriction on length, so I am free to really tell a story in the best way I can.

The Customer is Always Wrong is available now from Drawn & Quarterly.