Hillary Chute is an Associate Professor in the department of English at the University of Chicago. Since the publication of her first book "Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics" in 2010, she's been considered one of the most significant comics scholars in the modern era. She was Associate Editor of Art Spiegelman's "MetaMaus," authored the recent book "Outside the Box: Interviews with Contemporary Cartoonists" and organized the 2012 conference, "Comics: Philosophy and Practice." The conference was the genesis for this new issue of "Critical Inquiry," the noted academic journal published by the University of Chicago Press. To edit the issue, Chute partnered with Patrick Jagoda, an Assistant Professor in the Department of English and co-founder of Game Changer Chicago Design Lab.

During the course of their interview with CBR News, Jagoda mentioned his interest in the kind of reader the issue might produce. Containing conversations of some of the most talented cartoonists in the world, essays about various aspects of comics and new artwork created, the issue might be as confusing for academics that don't study comics as it is for casual comics readers. For those put off by jargon -- or don't understand some of the terminology -- some pieces in the magazine can make for challenging reading. At the heart of the issue, though, as both Chute and Jagoda made clear, is their love of comics and what comics can do, something they hope will inspire readers and future scholars of the medium.

CBR News: This issue of "Critical Inquiry" came out of the "Comics: Philosophy and Practice" conference in 2012. Hillary, you wrote that you wanted the conference to be about theory and practice being in conversation with each other. How did you attempt to make that play out in the issue?

Hillary Chute: The thing that I had felt frustrated with -- in terms of academics thinking about comics and cartoonists thinking about the intellectual issues that come up in the academy -- is that there doesn't seem to have been that great an exchange. I had gone to plenty of conferences where there were professors and grad students giving papers about comics and cartoonists. I wanted to try to do something a little bit different that would really make it more of an exchange; foreground the actual voices of the artists and put them in conversation with academics instead of having a conference built on the idea of cartoonists as the object and the academic as the explicator. In order to encourage a kind of exchange, I asked professors and curators to be in conversation with cartoonists. Every single event of the conference prominently featured artists themselves. Part of what I was interested in bringing forward is a conversation where my colleagues could realize that a lot of the issues they write, study and think about are issues that are also being thought about by cartoonists -- but from a slightly different angle -- and vice versa. I was really happy with how that worked out. We did not want to have a standard academic journal issue where it was just essays about the objects. We wanted the artists in some way to be able to speak for themselves, to make it a real conversation across the issue, which is why we have original artwork alongside essays along transcripts from the conference. It was really important to us to have a democracy of different kinds of voices in the issue.

Patrick Jagoda: We had a conversation very early on about how to structure these different genres -- the essays, the artwork, the transcripts -- and decided that we didn't want to have separate sections for each of them (to somehow suggest that they're completely different ways of thinking), but to really intersperse the essays with the artwork and the transcripts. We wanted to take comics seriously as media and as ways of thinking. That's true for a great deal of the media we cover. For example, comics are not merely illustrations and games not merely as entertainment forms, but ways of thinking visually and procedurally.

Chute: That's a great point. I think we talked about this a little in the introduction. There's this quote from Chris Ware that became the subtitle of a book of essays about his work, "Drawing is a way of thinking." We were primarily interested in trying to take seriously the idea of drawing as a way of thinking, design as a way of thinking, games as a way of thinking. This was the conceptual framework for the whole thing.

Just looking at the table of contents and seeing the artwork and transcripts that are inside, I remember thinking, "Do the academics who regularly subscribe understand what they're holding?"

Chute: [Laughs] I kind of think not, to be honest. I want to say, "Do you know how lucky you are to be receiving this journal in the mail as a subscriber?" I'm not sure.

Jagoda: It's a curious question. I think we wanted to de-familiarize what an academic journal is and can be. We wanted to make the process of moving through the journal difficult. We wanted it to be participatory. We wanted people to take time to make sense of how these different texts are relating to one another. We do some of that conceptual work in the introduction. We try to think through what the main themes are, including play and materiality and stillness and movement and hyper-mediation. We do try to offer a menu of concepts up front. I'm interested in the kind of reader this issue might produce and not just the existing scholars that it might speak to.

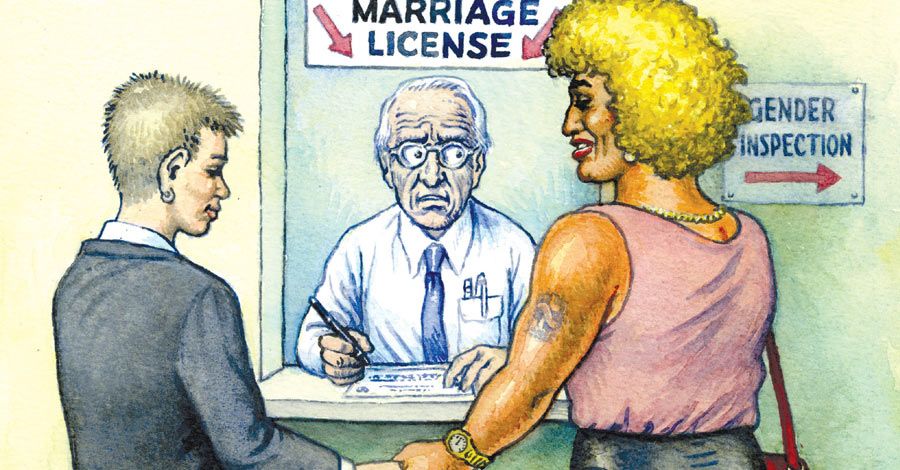

Chute: I've heard from academic friends who stop short at the cover. I got e-mails along the lines of: I never thought I would see a Robert Crumb image of "Critical Inquiry." [Oh my God]. I feel like even that cover immediately marks a very different kind of object for people.

Jagoda: I've heard from a few people for whom the issue is exciting even at a material level, which is something we were really hoping and striving for -- to produce an issue of "Critical Inquiry" that is larger than the usual size, one that's in full color, and privileges artwork and design as a way of thinking. I've heard positive and interesting feedback about that aspect of it. But I don't yet have an idea of how people are actually reading it.

Chute: To get back to your original question, we really wanted the form of the issue, and the online hub at "Critical Inquiry" that goes with the issue, to really instantiate this kind of conversation between "old" and "new" media. Patrick and I really cared about this being a meaningful printed object so we fought for and raised money for the foldouts, the endpapers, and all the visual artistic elements that aren't always in an issue of "Critical Inquiry." One thing I realized was how hard it is to make a lot of that visual work happen in the format of an academic journal. We really put a lot of energy into that and also into the online hub. We wanted it to be a meaningful printed object and also gesturing to other things at the same time.

Has all that work in making the issue the way you wanted it offered you a new appreciation for what it means to make a book?

Chute: I had that appreciation already from spending years talking to people and realizing what a struggle and how much work goes into each inch of a page of comics -- but yes, it felt like a fresh realization as we worked on this issue for two years.

Jagoda: Absolutely. I was working simultaneously on another special issue that was a little more traditional in its print layout. It had online components that were experimental, but the editing that went into the print component was much more textual whereas the layout for our "Critical Inquiry" issue required an ongoing collaboration with our visual designer. Because I'm not coming squarely from comics studies, it was interesting for me to think about the decisions about layout and typography and colors and resolution of images and how different pieces are interacting with one another.

Chute: One of the things that really felt like winning the lottery about doing this issue was getting to solicit from artwork from artists and then getting to work with them on it. For example, Phoebe Gloeckner's really fascinating weird experimental five page piece. Phoebe hasn't published a piece in a couple of years and so for her to accept my invitation for this -- and then to get a chance to really work with her on it and see drafts of it and see it develop -- was just an incredible experience for me as an editor. I hadn't worked with some of the artists who wound up contributing to the issue in this kind of editorial capacity before and I was just overwhelmed by their generosity in contributing. Someone like Aline Kominsky-Crumb -- an incredible cartoonist -- also has not published a stand alone piece just by her, and not a collaboration with Robert Crumb, in years. The fact that she said yes to doing this piece for "Critical Inquiry" was just incredible. It felt like a real and very special opportunity for me and for the "Critical Inquiry" community to be the home for this kind of work.

You got a comic from Françoise Mouly, which is a big deal!

Chute: I know! Françoise Mouly hasn't published a standalone comics piece in decades. It was incredible to me that so many artists were game to do work for the issue. I think a lot of that came from their positive experience at the conference. It was a way of reflecting that or giving back or continuing that conversation. To get a new piece from someone like Justin Green was just incredible. I could keep listing the individuals, but that felt like a really special feature of the issue.

After the conference took place, how do you go about conceiving and putting together this issue of "Critical Inquiry?"

Chute: We knew we wanted the issue to be a hybrid object. We knew that from the beginning. The conference was the germ for the issue, and we decided that we would publish every transcript we had access to. The only conference event that does not get reflected in the issue is the Ben Katchor lecture and that's because Ben Katchor has a book coming out that will feature a written version of this lecture. We were going to include everything from the conference, except Ben Katchor's lecture, and we invited every single artist who came to the conference to contribute original art. The ones who responded are the ones who are in the issue. In terms of wanting to reflect the conference we wanted to get everything in there that we could. In terms of the essays, we each did a triptych, if that makes sense.

Jagoda: The essays cover a number of historical and formal issues about comics. Historically, we explore the nineteenth through twenty-first century. For example, there's a Garland Taylor piece about Henry Jackson Lewis. Lewis was the first African-American editorial cartoonist, so there we were trying to move back to the 19th century. We talked to Tom Gunning who's a renowned film scholar to ask him to write about the panorama and film and the relation to comics. We wanted to include interesting historical material that moved forward to the contemporary moment. But we also wanted to de-familiarize comics. We did this by placing comics in a broader media environment and thinking about comics through a comparative media studies approach. To do that we produced two triptychs: one series of three essays was focused primarily on comics. We had pieces by Scott Bukatman, Tom Gunning, and Katalin Orban. All of those spoke of different moments in comics and situated them in different media environments: film, sculpture, and a multimedia digital media environment. The other triptych didn't have to do predominantly with comics. But comics entered into all three of the essays in different ways. We had a piece by Yuri Tsivian on Charlie Chaplin, Chaplin's transmedia aesthetic, and the way that he moved across media outside of film. Daria Khitrova wrote about ballet but in relationship to set design and lubok (which is a form of comics in Russia). There was an essay that I co-wrote with Katherine Hayles and Patrick LeMieux that had to do with an alternate reality game that tapped into the contemporary transmedia environment -- and comics were one of the many media that we were thinking about as we were putting that together. This diversity of topics offered a way of producing an issue that wasn't just a summary of comics studies at this particular moment but a way of thinking about comics conceptually in relation to a number of other media, which we thought might appeal to readers of "Critical Inquiry" in particular.

One thing that's been mentioned is how people in the audience -- Robert Crumb in particular -- would comment or shout during the panels.

Chute: It was so great.

Does that happen a lot at academic conferences?

Jagoda: [Laughs]

Chute: [Laughs] No! This is part of why this conference was such a pleasure. I think it made some people uncomfortable in a good way. Our colleague Tom Mitchell -- who's the editor of "Critical Inquiry" -- said, that should be a model for academic conferences moving forward. There was this incredible participatory aspect to it. Crumb sent me this postcard, which is reprinted in the introduction, where he says I'm worried that people are going to be bored. Remember this is about comics. I don't want to go to a boring conference. He was the opposite of bored. He was sitting in the first or second row having a talk back at every one of the panels. That was incredible. During the Tom Mitchell/Joe Sacco conversation, Joe Sacco put up an image of a rejected spread from "Palestine" and Crumb yells out "too technique-y!" He was giving a running criticism of the images as they were coming up in an engaged, sympathetic and participatory way. That was awesome. I loved that part of the conference. It made everybody think about what it means to really participate as an audience member in the conference, which is what I wanted. There were no competing sessions. Part of what I was thinking was giving cartoonists to get an opportunity to hear from other cartoonists and trying to think about the conversations that will come out of that by putting some of the best people in the field in a room.

Jagoda: This project emerged from a variety of influences and it came in part -- not to speak for you, Hillary -- out of Hillary's experience of working with Alison Bechdel as an aspect of the grant that she received from the Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry at the University of Chicago which brought Bechdel in to co-teach a class, work on her own work and they also collaborated on a one page piece that made it into the "Critical Inquiry" issue. I think that kind of collaboration between scholars and artists was already at play in Hillary's work before the conference ever started.

Hillary, in your introduction to your book "Outside the Box," which came out earlier this year, you talk about the importance of the interview, especially as it relates to comics, because there's been little scholarship until recently so most of the theoreticians and scholars were cartoonists. That having them talk to each other leads to ideas and thoughts that we don't often get.

Chute: I thought that that part of it was incredible. I don't mean to tout the panel that I personally moderated, but to name one example, there was a panel called "Graphic Novel Forms Today" and it was Seth, Chris Ware, Dan Clowes and Charles Burns. It was one of those moments where I learned so much in an hour and a half of that panel listening to them talk to each other about comics forms. It was that kind of experience that I hadn't really encountered much before. These incredible cartoonists and thinkers bouncing ideas off each other so I loved being a witness to that.

You're both members of the department of English. What's the overlap of your work and what you study?

Chute: My interest in comics -- this isn't the angle that everybody's coming from -- is thinking about comics as an "old media" form. I'm very interested in comics in relation to the history of the book. I'm very interested in comics in relation to print culture. I'm very interested in thinking about why comics as a form has re-emerged so powerfully even as people are lamenting the decline of print. I'm interested in comics as a material object, as a printed object. It was so interesting to have Patrick as a colleague who is coming at the form -- and other forms -- from a slightly different angle, one of "new media." I think we were both really interested in trying to think about media studies from a slightly different angle than it's been done, and so to try to think about media studies through comics historically, if that makes any sense -- to bring "new" and "old" together.

Jagoda: I was also interested in working with Hillary on this because I saw so many overlaps between comics and the new media that I usually study. So one thing that we say in the issue for instance has to do with comics being a "cool medium" in Marshall McLuhan's term. In other words, it requires substantial readerly involvement. I like thinking of comics as a participatory medium even though that sense of the "participatory" tends to be applied more regularly to video games and digital media and interactive fiction, but it's at play in the ways that comics slow down our reading speed, plot our movement across pages, and require us to attend to medium specific features. Also, I was interested in the ways that different forms of reading play out in comics, which is something that Hillary writes about as well. We had a couple essays in the collection that talk about hyper-reading and hyper-attention versus this slowing down when you're looking at a page and taking in the relationship between text and images.

Chute: I think one big area of intellectual overlap between video games and comics that we're both really interested in is the idea of the ludic and what is play and how do people enter a certain space of narrative and how do they navigate that. That was a really big link between comic books and video games for us when we were thinking about this issue.

Patrick, I know you study "network aesthetic" mostly in terms of digital media but I think that idea is prevalent in comics and the medium is very well suited to it.

Jagoda: That's absolutely right. Comics like Warren Ellis' "Global Frequency," for instance, are all about network actors and collaborators coming together to solve problems. Even in the realm of superhero comics, which we don't do as much with in this issue, we're moving from the figures of heroes and superheroes towards more collaborative groups like we see in "Global Frequency" or some "Iron Man" comics. Those kinds of network aesthetics interest me. Part of what we talk about in the issue also has to do with the movement from comics to games and games to comics and forms of adaptations are taking place in both directions. The ludic and the playful dimensions that Hillary is talking about are marked differently on a static page versus the kind of animation that you have in a video game, for instance. How do you think about comics differently when you situate them within convergence culture and a transmedia environment? How do comics look differently when you talk about them in relationship to films and the panorama -- as Tom Gunning does for instance -- and video games?

You're both member of the English department and there are a lot of comics scholars that come out of English departments. Do you think that how we talk about comics -- both academically and popularly -- is too defined by literature and those approaches?

Chute: One of the things that's been fascinating for me going around and giving talks at different schools is seeing how that's a little different than I thought. For example at Stanford where Scott Bukatman teaches -- he's a contributor to the issue -- the interest in comics is really coming from the Art History department where he's located. It's been interesting to see how different schools and different disciplines vary in terms of where the interest in comics coming from. I've taught a class on "The Chicago Graphic Novel" and a lot of my students were art students and they were fantastic. They brought so much to the class in terms of their background and their ability to talk about line and texture an shading and style. I hope that's just us. I think that one of the powerfully interesting things about comics is how it requires vocabulary from all sorts of different disciplines. It's not monolithic.

Jagoda: That's true. You see an interest in media studies, an interest in comics and architecture, all kinds of interesting intersections. When I teach comics, they're not as central to my courses as they are in Hillary's classes. But, for example, I'll teach a course on "New and Emerging Genres" in which I focus on the innovations in narrative in the last twenty-five years and the end of that course takes up autobiographical comics in relationship to autobiographical video games and thinking about how the affordances of a piece by Spiegelman or "Persepolis" relates to a video game like "Dys4ia" that's trying to convey a narrative through procedurality and interaction and a world that you can navigate in different ways. That juxtaposition can be really productive and moves students across numerous media.

One thing that's come up a lot in discussions around the conference is this idea of a comic canon. You mentioned that you wanted to gather some of the masters of the form. What does it mean to create a canon?

Chute: I don't know because that's not my goal. I think the idea of a "canon" has become unfashionable in critical theory, but I think plenty of people are interested in creating canons.

That's true -- and many people have different reasons for doing that. But I think that one reason is because every medium has a canon -- so why shouldn't comics?

Chute: This has come up a lot when people talk about the conference, and Patrick, I'd be curious what you have to say. When I say that I was interested in inviting masters of the form, that's totally true. It's not as though every single master of the form was there. I was interested in inviting people whose work I thought had made a really big impact on me and broadly, culturally over time. So there's that. I think that I don't feel the same anxiety that other people feel about this idea that academic study is going to rob comics of its vitality. I feel like comics is such a vibrant and energetic form, it's just impossible. If "Persepolis" and "Maus" get taught a lot in college classes, it's hardly sapping energy from the comics community. More conversations are always better. More teaching of texts is always better. It just doesn't seem like a danger to me. It seems like only a positive.

Jagoda: I totally agree. It's worth thinking about a canon not just as a list of books. I think people are very invested in top ten or top one hundred lists, but one thing that I liked about the way that I perceived you putting together the conference, Hillary, was that if you were approaching a canon of comics at all, it was as a way of reading, not as a list of books. What does it mean to read comics in a particular way? I saw you asking: What does it mean to look closely at comics not just in a way that academics do, but the creators themselves, and try to analyze that for people who are interested? Thinking about comics as a process or thinking about the canon as a process and not just a static list is important.

Chute: That's such a good point because if you look at someone like Crumb, I don't think that there's one book that stands in for Crumb. That's much more of an English literary studies kind of model -- the list of books -- but it doesn't necessarily apply to some of the most compelling figures in the field. Someone like Robert Crumb, who's done a bunch of serial work in all sorts of different contexts, that accumulates and adds up to something paradigm-shifting but it's not as if there's one work that stands in for him in the typical way of canon.

Jagoda: That kind of impulse was underlying the way we were putting together the issue. I don't think that any of the contributors were interested in either delineating a canon or defining exactly what comics are and aren't. There were little debates along the way but many of our contributors like Tom Gunning and Scott Bukatman were much more interested in careful analytic description of the art form and of the way that different creators experiment with the medium and its affordances.

I feel like many conversations about canon -- not just in comics -- can be about who's loudest, who's most prominent, who's published recently. One of the things that we can do by having conferences or conducting interviews is to draw attention to people and say, for example, Phoebe Gloeckner has not published a new book in years, but she's a genius and one of the best cartoonists alive today.

Chute: No kidding! I totally agree with that. I feel like being able to give her a platform -- not that she needs me for a platform -- but to have her at the conference was so meaningful to me. I consider her a one hundred percent genius, but it's not like she's super-prolific and on everybody's radar in the way that Art Spiegelman is. In that sense there was a range of different kinds of artists there.