A few months back, in response to a viral essay penned by Devin Faraci, I wrote that fandom isn't broken. As it turns out, I was wrong.

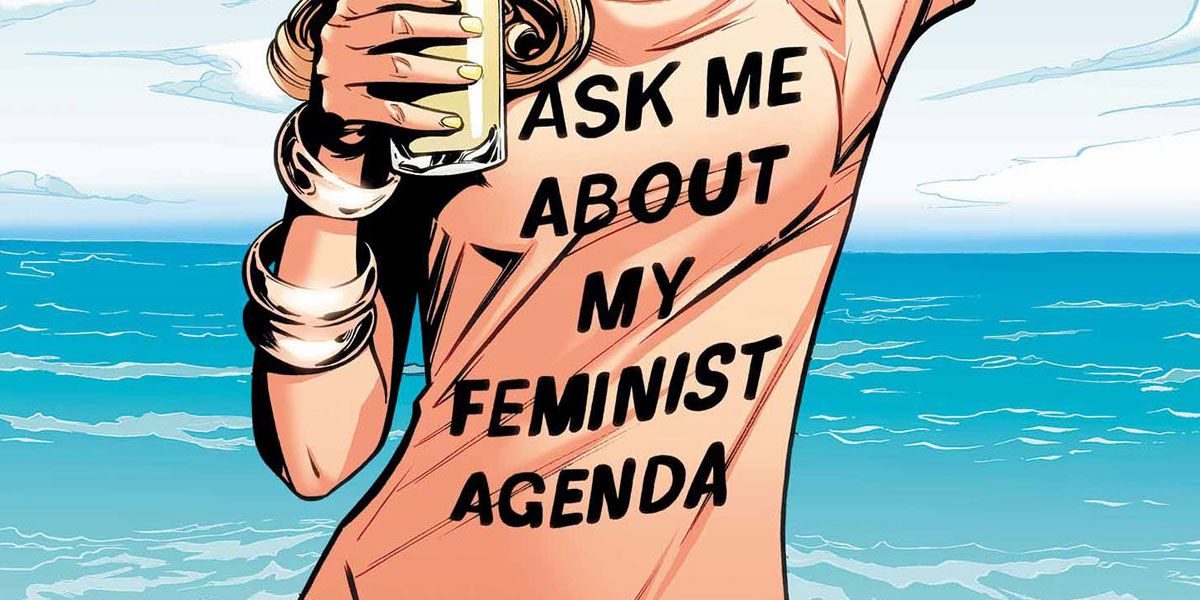

Earlier this week, the cover to final issue of "Mockingbird," illustrated by Joëlle Jones and featuring the title character wearing a shirt that read "Ask Me About My Feminist Agenda," inspired a torrent of abuse on Twitter toward writer Chelsea Cain, who ultimately quit the social media platform rather than continue to weather the barrage of nastiness and threats directed her way by people whom she'd never met.

This isn't the first case of an entertainer, almost always female, being driven off Twitter because a "fan" was not entertained. The problem is well documented by this point, and really, nothing has changed between now and my previous response. But my initial reluctance to see the problem as having to do with fandom, specifically, is borne of I think two primary factors: First, I assume that the comics community is roughly representative of the broader world -- if some comics fans are assholes, that's just because some people are assholes -- and second, I tend to look for the best in people. They don't understand, they over-react, etc. I want to examine the bad in context, always reminding of the good.

But I am not a target.

As your Resident Cishet Whiteguy, I do my damn best to be aware of my privilege. I try to be aware of the conversations being held around representation and diversity, supporting various efforts as able, and recognizing that my voice is, in general, not what's going to push these things forward. I want to be conscious of the biases I will never experience directly, and take into account how they can affect a person's actions in less obvious ways. I fail at this when I do not take into account comics' (and certain other fandoms') unique power dynamics.

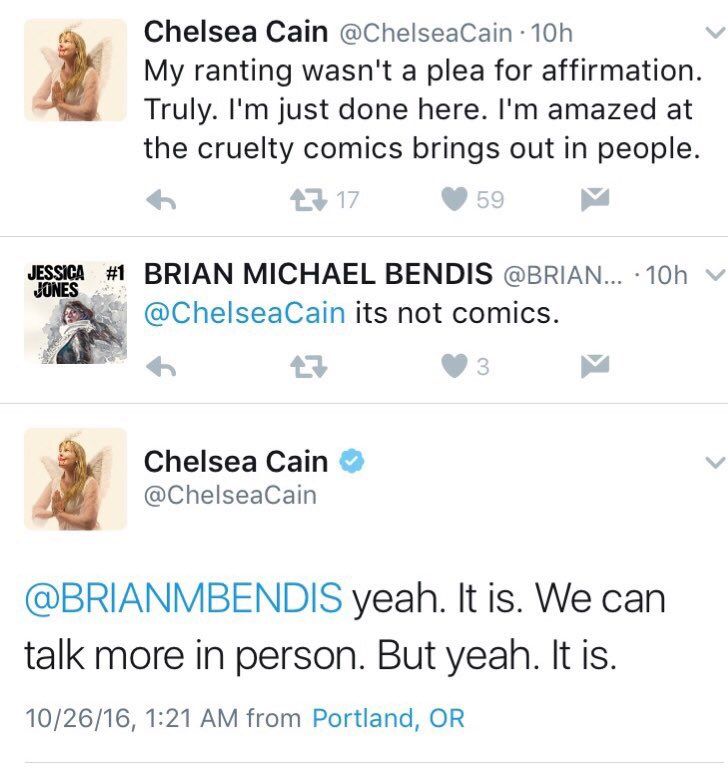

The exchange that woke me up was this one:

It's so sad. And rings true. Chelsea Cain is a successful novelist, and when she says she never experienced this sort of harassment from her prose readers, it's pretty safe to believe she's telling the truth.

Bendis was quickly taken to the mat on Twitter for "mansplaining," which may be fair, but it's important to note that he and Cain are friends in real life. This is not insignificant. He is not a rando telling her that her problem is not a problem, but a friend attempting to voice support. If it's bad advice, if it's ineffective support, even if he's completely wrong -- who hasn't had a friend do similar? I've been on the giving and receiving end, myself.

In a statement released after she quit Twitter, Cain reinforced that Bendis is not the problem. “I want you all to know that he is one of my dearest friends, a mentor, and someone who absolutely has my back,” Cain wrote. “I thought his tweets were supportive and awesome. I went to bed thinking his tweets were supportive and awesome. Somehow, by the time I woke up, a whole other narrative had formed. We were friends, talking in the middle of the night, and we were talking like friends, in the sense that we know each other and we’ve had larger discussions that provide context for his remarks. He’s right, by the way, there are misogynistic twerps in all industries.”

If "there are misogynistic twerps in all industries," though, is comics fandom really the problem? Aren't there bigtime examples in other creative fields? Sure. It wasn't so long ago "Ghostbusters" actress Leslie Jones was driven off Twitter by an especially nasty, coordinated campaign of abuse. The "fandom" there, though, is similar in kind to comics -- folks with a fierce sense of protection for a piece of entertainment they claim to love, willing to lash out at those who threaten their sense of ownership. It's not just comics, sure, but it's unusual for an entire medium to invoke that sense of a walled garden -- it would be hard to argue, for example, that the "Ghostbusters" harassment is suggestive of an endemic problem in film fandom (though the film industry of course has its flaws).

What about gaming? Yes. Yes yes yes. The problems of comics fandom are on full display in gaming, a sneering superiority among the traditional "base" and propensity to attack those who attempt to introduce new elements, to attract new audiences, up to and including releasing personal information online and issuing physical threats making these women -- almost always women -- genuinely fearful of making public appearances. It's not just comics. But it is comics.

Comics have traditionally been a boys' club, both at the fan and professional level. The democratization of content through web comics and other innovations, as well as social media's ability to form communities to amplify voices, has done a lot to push back against this trend, and the major publishers are, in their own ways and with their varying degrees of success, working to course correct. New creators telling their own stories builds audiences as more potential fans see themselves represented in "mainstream" comics; it should not surprise anyone that this would be appealing to publishers, nevermind the inherent moral value.

But it's hard to swim against the tide. On the professional side, allegations of sexual abuse against certain editors are just now being made public despite some of them being an open secret for years. Some male creators who claim the badge of feminist have their own incidents of abusive behavior, and following the attacks on Chelsea Cain several female creators tweeted about "allies" who stand by abusers. It's a small industry. People talk, and that is useful, but it's a slow path to change.

And on the fan side, there's that sense of ownership. Why make Captain America black? Why make Green Lantern gay? Why make Thor a woman? Can't you just create a new character? These heroes are spoken for! Nevermind that yes, new characters are created all the time -- some of them are even straight, white men! Nevermind that these characters are icons, that they come with a cultural cache straight off the bat that a new hero simply isn't going to have -- that a black Captain America is inherently more meaningful than a black USAgent, that representation is therefore more powerful when incorporated into a known, beloved hero.

That ownership has also been shown to extend to tropes as well as heroes. The recent controversy over J. Scott Campbell's cover to "Invincible Iron Man," which portrayed teen hero Riri Williams in what many perceived to be an unnatural and overly sexualized pose, was the latest in a series that set the activist comics community against the old guard. Is it censorship to slate a piece of art that serves up a fifteen-year old girl as a lollipop, to tear it apart for its unlikely depiction of teen bodies and fashion, or just solid art criticism? Are Campbell's defenders truly concerned about artistic expression, or only clutching fast to an era where eye candy was a matter of course? When comics were for them, and them only?

RELATED: Marvel Pulls J. Scott Campbell’s Riri Williams Iron Man Cover

It's not just comics, and it's not just fandom. The true ugliness that this election season is ample evidence of that. There is a broad culture of social media abuse. But comics are a special case because of the nature of the community. And the rules about political echo chambers on social media applies here, as well -- if you believe that everyone is on your side, you can feel justified in heaping scorn and abuse on those who disagree, who dare to create something that isn't tailor made just for you. If you believe "SJWs" are ruining comics, and all of your friends agree, then attacking the creators of a comic that dares to proclaim itself feminist is not only allowed but virtuous. That'll teach them.

Why, then, do pop culture creators bother with Twitter? Why did Leslie Jones, who endured some truly horrific cruelty, come back? Outside of professional promotion, I think the appeal for them is likely the same as for most people: there really can be a sense of community. Pros can talk to each other; pros can talk with fans, actual fans who enjoy their work. And especially for folks who are underrepresented in their chosen fields, that can be extraordinarily valuable. For those with an "agenda," it has the power to affect change. Publishers might still make questionable hiring decisions, or release artwork inappropriate to the story at hand, but they're going to hear about it -- and so are casual readers, those who might not read CBR every day or plug in to "woke Twitter," but who nevertheless may have something to say about how women are portrayed in pop culture -- and how they're treated behind the scenes.

But Twitter abuse is a thing, and I was wrong to believe that it's not especially a thing in comics. Chalk that up to privilege. Read the incredibly smart women who tackle this head on, women like Zainab Akhtar, Swapna Krishna, and CBR's own Casey Gilly. They know what's up.

Why have I just poured 1500+ words onto the web, then? I don't doubt that some will view this article as part of the problem, of making this event about me, the cishet whiteguy. But I write in acknowledgment that we've all got to be better.

In her statement on quitting Twitter, Cain wrote that “Comics readers are 99 percent the best people you’d ever want to meet. The other 1 percent can be really mean." The #NotAllFans mentality doesn't help. Be kinder -- it's actually ok to not like a thing and not say anything at all. Call people out on their BS, even if it's your friend, even if it's an Important Industry Figure. If you see abuse, report it -- Twitter keeps saying they're going to get better at handling attacks, maybe one day they actually will. And please, especially if you've "never experienced that," listen to people who have.