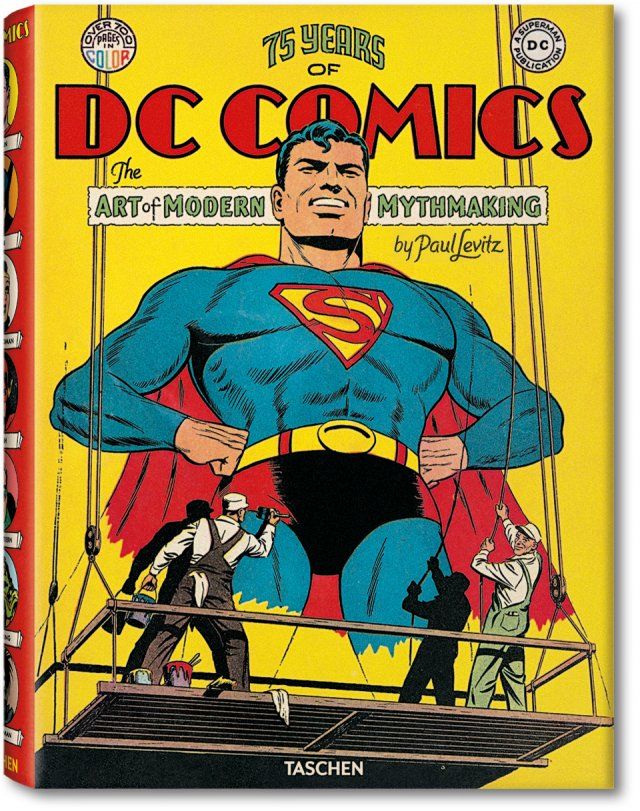

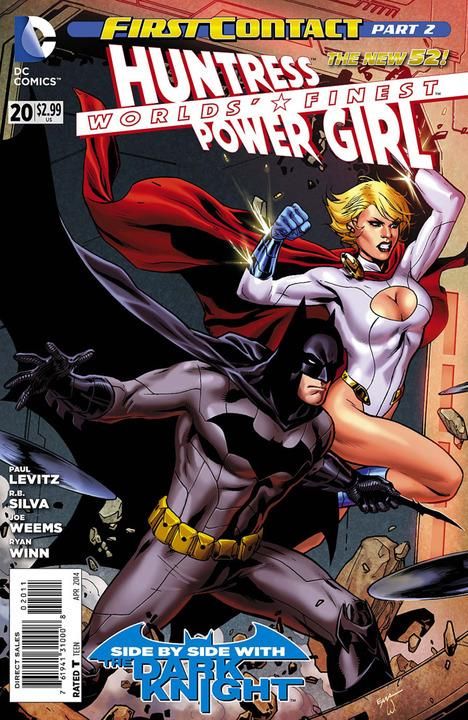

Since stepping down in 2009 from his longtime position as president and publisher of DC Comics, Paul Levitz has focused much of his attention on teaching and writing, with projects like World's Finest and Taschen's expansive 75 Years of DC Comics: The Art of Modern Mythmaking.

Currently he's putting the finishing touches on a book about his friend Will Eisner titled Will Eisner: The Dreamer and the Dream, while teaching college courses. In addition, he recently joined BOOM! Studios' board of directors.

For a man who made his name writing adventures of the future in Legion of Super-Heroes, you had to know Levitz had plans for his own future, right? I caught up with Levitz earlier this year, at a particularly busy time, to learn more about his activities since leaving DC's executive suite. We spoke before the BOOM! announcement was made, but we had more than enough to talk about in our interview.

Chris Arrant: When I initially reached out to you to do this interview, it was on Thanksgiving week and you were in China at a digital publishing conference. Despite leaving DC, you seem to keep a real busy schedule. What’s work life like for you these days?

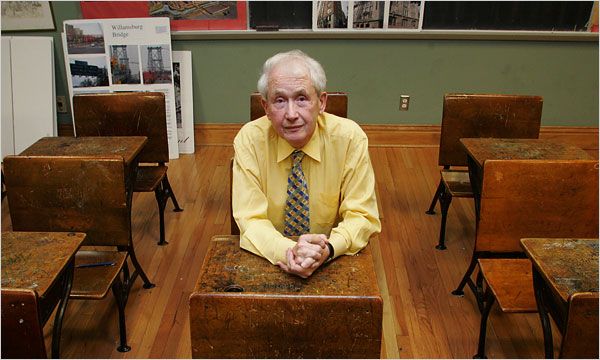

Paul Levitz: About 50 percent of my time is spent doing teaching, or teaching-related work. It’s something I always wanted to do in life, but America’s approach to teaching doesn’t necessarily make it a lucrative profession. It’s something I’ve been waiting to do when I wasn’t primary concerned with the economics of it.

I’m teaching writing at Manhattanville College, and transmedia courses at Pace University, and it’s Pace which led me to go to China. They’re a co-sponsor of a biannual publishing event, and I was one of last year’s keynote speakers. It was an interesting experience.

So with teaching being about half of my life, the other half is a mixture of writing. Doing comics for DC, working on a book about Will Eisner for Abrams ComicArts, as well as some other odd little writing projects. I’m also doing consulting and business advice in one fashion or another to companies where I can be useful. I still do a little bit for Warner Bros., but not much anymore.

When DC announced you were stepping down, I remember a quote from then-Vertigo head Karen Berger saying there was talk of you doing a Vertigo book. You and Vertigo sound like quite the pairing – what ever came of that?

I played with an idea for a Vertigo graphic novel early on in the process, but there was so much superhero stuff DC wanted me to do that it pretty much took all the writing energy I had. As for doing it now, we’ll see where my path leads me.

Levitz Brings 40 Years of Experience to BOOM!'s Board of Directors

And what are you working on today, specifically?

I just came back from a museum in New York City, where we were discussing an exhibit on comics for 2015, and talking about different people in the field they could contact. It’s shaping up to be a cool thing, as one of the things we talked about was the days of Ross Andru, who would climb on top of the buildings in NYC to inform his artwork more for skylines in comics.

Since your departure from the president/publisher’s office at DC, you’ve begun writing non-fiction books – first the massive 75 Years of DC Comics: The Art of Modern Mythmaking (which is being broken up into standalone books now), and I read that you’re putting the finishing touches on a book about Will Eisner. Is this something you’ve always had in your mind to do, or something new that came along recently?

The books are, to me, an extension of my having been a comic fan all my life. I started out doing fanzines about comics, and talking to artists on the history of comics. Not in a very academic or scholarly fashion, though, as I was a kid at the time – but the subject has always interested me. Now, having the freedom (and the time!) to pursue it further, I’ve worked with publishers who can make these beautiful books like what Taschen did with 75 Years of DC Comics and the excerpted books spiraling out of it. It’s been an enormous undertaking.

From the sounds of it, the Eisner book, Will Eisner: The Dreamer and the Dream, is virtually complete on your part. What do you have planned next?

I have a couple of projects in my head. Some nonfiction, and some original fiction.

You mentioned consulting work – now that you’re not employed by DC, I assume you’re able to do that for whatever and whomever you want. What’s that been like, and what has it been comprised of so far?

It’s still in the pretty early stages, but It’s something I’ve thought about doing for a while. Fading out of an executive role, it’s given me a freedom to do things progressively greater as the number of years climb away from that desk.

So far I’ve done little bits and pieces of things; everything from working on a digital app for kids to talking with people about the development of a intellectual property for animation. I’m open to anything where people think I’d be useful.

As you’ve said, teaching takes up a large part of your life these days, and you’re seeing potentially the next generation of writers and comics creators. What do you see that’s different from your generation to this younger generation?

My courses haven’t really focused on teaching the creation of comics, and it’s not comics writing per se. I’m seeing young people who will use writing as part of their skillset going forward; a couple of them may turn out to be creative writers in comics, prose, film or elsewhere, but a larger number of the students are majoring in communication, business, educating or marketing; or just need to build skills in writing, because as you know it’s the core form of communication. Regardless of what kind of jobs you have over the course of your life, it’s proven you’ll have greater success if you can communicate well in writing. If you can learn to tell a story, it becomes a nearly universal skill to use.

It’s great fun working with young people, and watching people’s skills develop.

Well, I was lucky to have a half dozen extraordinary teachers, including Frank McCourt. Frank is the only famous one of the bunch, because of the way his life took him. What I got from each of them, whether it be in English or Accounting, was the opportunity to learn from someone who had genuine passion for the subject matter and a broad view of how it sits in the world.

In McCourt’s case, a lot of what I remember from those classes was his enthusiasm for a wide range of literature from all over the world. I got to read things like Chinua Achebe, which isn’t part of the conventional high school reading list, and we also got to talk about them. Frank pushed us to think about very different styles of literature, and look into aspects of the world that was very different from my limited exposure as a kid growing up in Brooklyn.

Frank loved language, and was an extraordinary speaker. The closest analogue to comics is the fact that I heard real stories from him. He had such a distinctive speaking pattern; such an expressive voice as a reader. Years later when I read Teacher Man, I heard the brogue rolling off his tongue and remembered more from his classroom. I think giving kids a sense of your own joy is what teaching is about.

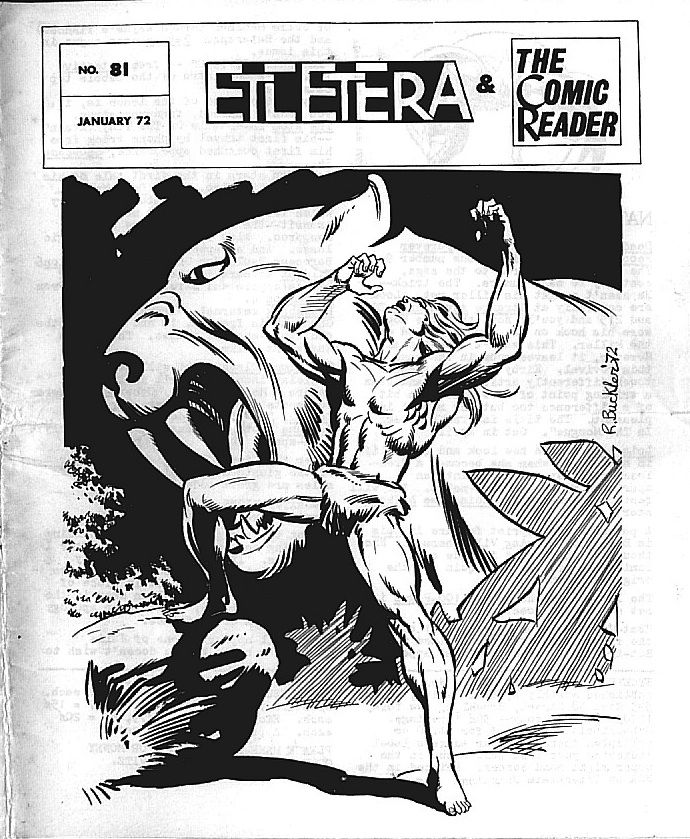

You entered comics age the age of 14, doing a comics fanzine called Etcetera and then talking over The Comics Reader – the first regular comics fanzine. The idea of you as an old-school newshound has always fascinated me -- what was it like back then?

It feels today’s youth talk about those times like it’s the dinosaur age.

[laughs]

Back then in the 1970s I would go up to the offices of DC, Marvel, Gold Key and Warren on a regular basis; pretty much all of the characters were created in New York then. I would go there and just hang out; talk to people, interview people, get information, look at their production schedule, and just finding out what’s going on. Then I would rush home and type it all up on a manual typewriter, paste it up with rubber cement, and race to a quick-print operation. A week later I got it back from the printer, and I’d assemble a gang of friends withi pizza to help me staple and address them all by hand. Compared to what’s possible today with desktop publishing and the Internet, it’s no even in a physical form at all. It feels like we’re talking about stone tablets and chisels, but it’s only a generation ago. It’s wonderful.

You left journalism behind when you took a job at DC, but how do you feel about what comics journalism has evolved into?

Well, let’s be broader than comics journalism; let’s talk about writing about comics. There’s a sophistication to some of them, to a scholarly level, which I’m thrilled to see happen. Years ago I wrote an article for The Comics Journal titled “Call for Higher Criticism,” and looking back at it I think it was very naïve and immature in many ways. The argument was that there’s more to talk about than if the Thing can beat the Hulk, but there was broader things to talk about. I’ve seen it evolve over the years, with an army of professors now bringing scholarly knowledge and wisdom to the field. You asked earlier about what I’m working on next; I just finished contributing to an updated edition of Matt Smith and Randy Duggan’s Power of Comics. It was a wonderful experience to be invited to join as the third author for this second edition.

Speaking about the state of comics journalism now, however, and most of it's terrific. There’s an enormous amount of information available now that wasn’t accessible back when I was doing it. But there’s some things that come out, and the tonality of it makes my shudder. It’s snide and personalized in a way I hope I never wrote, and not something I ever particularly enjoyed as a reader. But if you’re going to have a broad conversation, there’s going to be a lot of people talking about a given topic – and in a big conversation, you sometimes have to put up with someone being a snarky ass.

How did working as a fan journalist in the 1970s influence you when you took a staff position at DC?

It’s hard to parse what influenced what and in what way. Certainly running a publishing process from the ground up helped me, as well as working on books for comic conventions and tracking down talent; but obviously DC was at a much bigger scale. I lot of stuff at DC I learned while on the job.

Working at DC back then, you could really see there was magic going in in that place. Some things I learned from my peers at work, but a lot of what informed what I did in my career was learned around the poker table after works. In those days of comics, staff and creators would meet up on Friday nights to play cards. People would come and go, but at least half a dozen of the people who played at those tables ended up being editor-in-chief at Marvel, or leading editors at DC, as well as many future superstar creators; and we were all there talking about what comics were and what they could be. I learned a lot from them.

I also had several mentors in the field: Joe Orlando, Jenette Kahn, Gerry Conway were all people who I learned from at different points. I remember sitting with Steve Gerber and Gerry Conway while they argued about what comics could be and how this field should grow. All of that kind of thing influences me with the choices I made going forward and what new things I would try.

And now as you’re out of the executive suite, you’re catching up on lost time as a writer – but you’ve already written a lot. Are there still some goals you’re aiming to do as a writer?

Definitely. Most of what I’ve written in comics has been superhero material; it’s probably the most commercial thing I’m able to do. I’m thrilled when I run across people who grew up on that stuff. But I think there’s so many more stories I can tell, and I hope I can do that now.