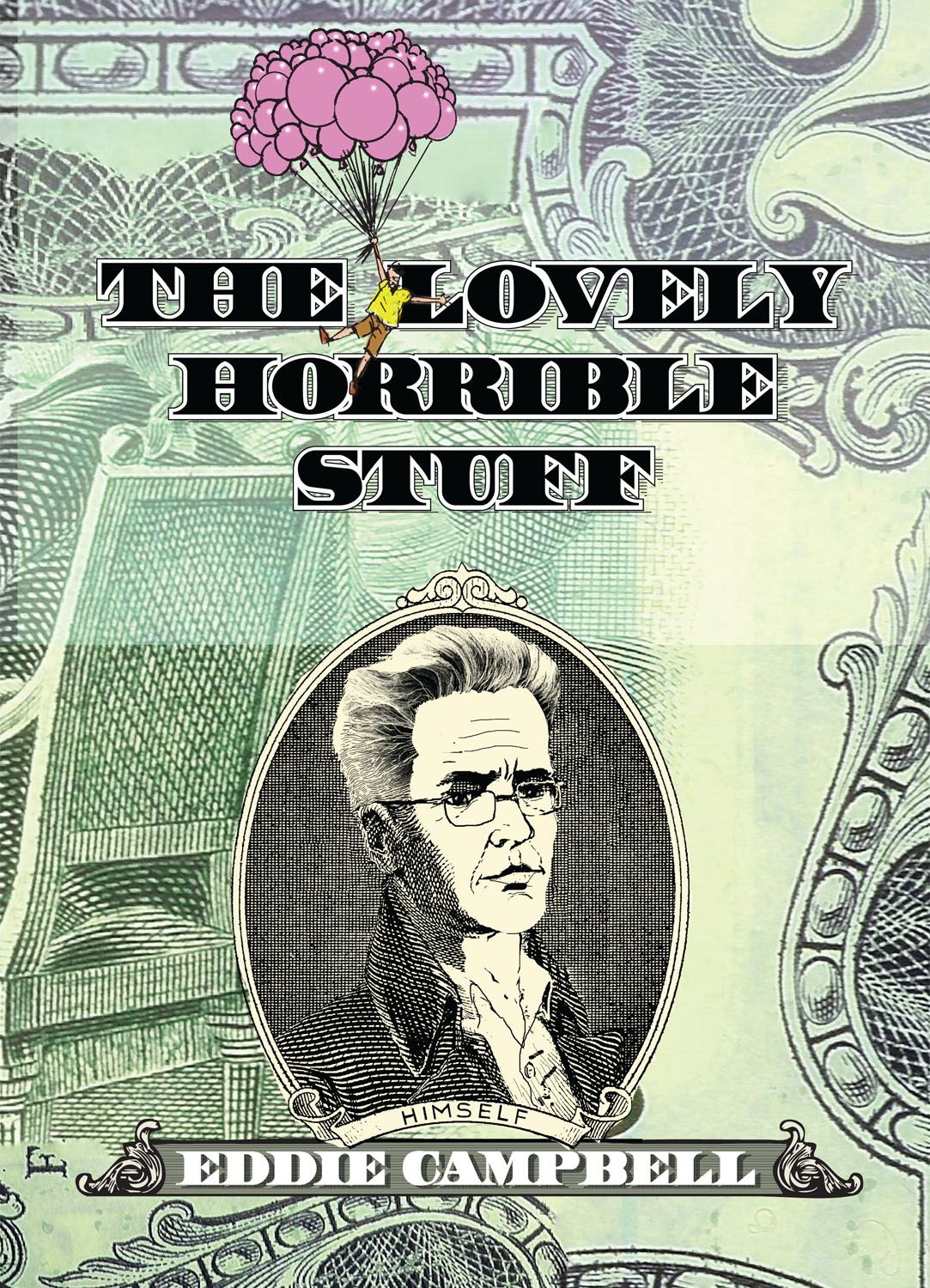

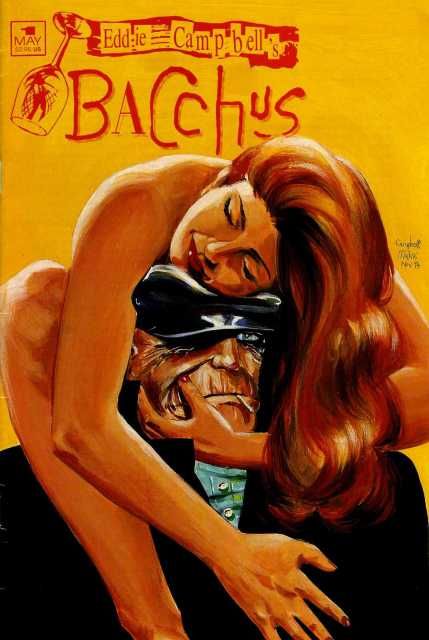

Eddie Campbell has made a name for himself among the upper echelon of modern comics creator, both for his collaboration with Alan Moore, From Hell, and for his own stories like Alec, Bacchus and the recent, great look at the concept of money, The Lovely Horrible Stuff. He's created a lot of stories, but he's far from finished.

This summer William Morrow will release the cartoonist's illustrated version of Neil Gaiman's The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains, and Top Shelf will publish a two-part omnibus edition of Bacchus. In addition, the Glasgow-born artist is working on two new projects, the first being a book about the roots of sports cartoons in late 19th-century San Francisco, and the other a collaboration with Audrey Niffenegger, author of the smash prose novel The Time Traveler's Wife. ROBOT 6 spoke with Campbell about these upcoming projects, as well as his past works and the stories behind them -- including last year's From Hell Companion, which he compiled and wrote using never-before-seen materials from both himself and Moore.

Chris Arrant: What are you working on today?

Eddie Campbell: Today I'm working on a collaboration with Audrey Niffenegger.

Author of The Time Traveler’s Wife. Interesting. I heard second-hand that you were working on a book about sports cartoons. Is this one and the same, or another project? Can you tell us about it?

That's another project. The one thing in the world that has always interested me most is the biography of art. I don't mean the sentimental drama of poor old Vincent Van Gogh and how nobody would buy his paintings, but rather the life of ordinary artists and how they did whatever it was they did. I always had an idea of writing a history of some sort because I have always enjoyed reading books about art and the artist. So I think I have found a subject that has never been properly investigated. The story of cartooning in San Francisco in the 1890s and how the sports cartoon developed out of it. I have always wanted there to be a book about this so that I could know more, but the people who might have written it are all dead. So it has fallen to me to figure it all out. I've written it and it's done, at 70,000 words. I'm currently restoring old pictures. But anyway, it is full of drama and odd twists and turns. There are race riots and somebody being shot in the head. This is no dusty academic tome.

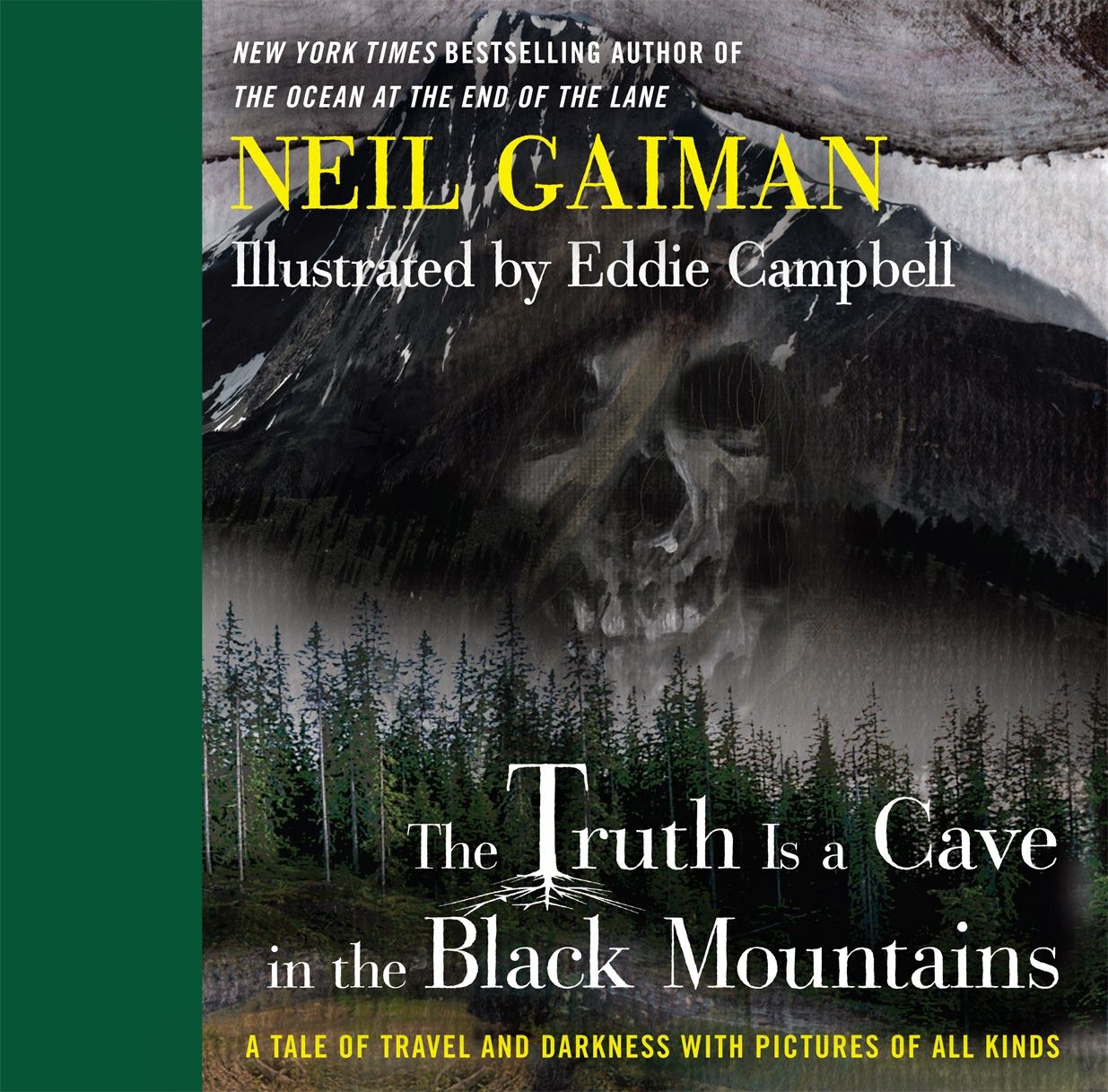

According to my research, in addition to those two projects you have two more books coming out in 2014: an adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountain and the long-awaited Bacchus Omnibus. Can you give us an update on the release date of those projects?

The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountain is coming out in June, and we're going on tour with the performing part of it. The Bacchus Omnibus is still to come.

I don't mean to be rude, but can you explain what the delays are for the Bacchus Omnibus?

Oh, you rude fellow. We're still working out whether to do it as a digital thing first, an eBook or whatever you call it.

The news about The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountain is great; can you give an outline of what the tour will consist of -- Neil and you and who else? And what cities do you think you'll visit?

It's still being pinned down, but definitely London and somewhere in the U.S.. It'll be the show we did before, with the band and everything, but I've updated the pictorial accompaniment.

The original presentation of The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountain was at the Sydney Opera House as part of a performance and reading. Was that its original intended form and this graphic novel something later, or was the end goal always a graphic novel?

The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountain began as a commission to put on a performance as part of the first Sydney Graphic Festival in 2010. It consisted of Neil reading his story of the same title at the Sydney Opera House. The story hadn't yet been published when we planned the whole thing, though it was out by the time we fronted up on stage. Behind him were projected three dozen painted illustrations I made for the event, and off to the side the string Quartet Fourplay performed music they composed specially for the show. it was one of those complicated things we thought couldn't possibly work. The whole thing was planned, as was the festival in fact, by Jordan Verzar. But that was part of the exhilaration of it, a feeling that we were in public with no belt to hold up our trousers. The show was an overwhelming full-house success.

Well, in this business, as in any business, you're always looking to maximize the exposure of the work. No sooner was the live event finished than I was thinking about taking the illustrations and the text and weaving it all together in a book. It took quite a bit of work and I added a great many more pictures to make it all run smoothly from beginning to end. I was very excited to see it go to the printer, and today I’m looking at the first set of proofs. I feel very pleased indeed. It should out in June.

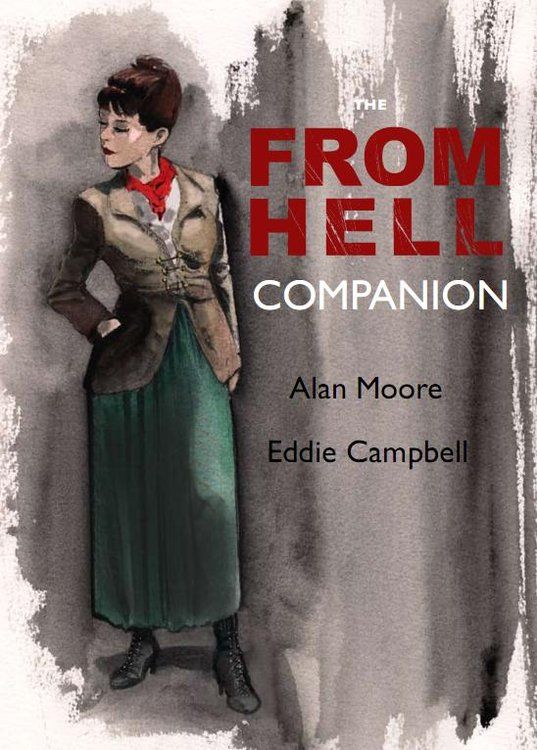

Going from talking about future books to ones in the recent past, last May Top Shelf put out the From Hell Companion. You finished the original serialized story in 1996, but the scope and detail you did for From Hell Companion it's as if you were back in the thick of it. What was it like revisiting those pages and those notes, especially in laying it all out chronologically?

Yes , It was weird to revisit From Hell. But on the other hand, I felt as if I’d been carrying around all that information in my head for 20 years. When I decided to do the book, it all spilled out in a torrent, more or less in order. The From Hell Companion was like reliving the book from a bunch of different angles simultaneously, and It should be for the reader too.

The approach you take with the From Hell Companion is far more ordered than most other similar texts, as you're telling a narrative story about the making of the comic from the ground up -- similar to how you and Alan Moore depicted the Jack the Ripper murders in a holistic manner. How'd you go about deciding to take this approach, and was there any hesitance to be so thorough?

As I've gotten older I've become very tired of linear storytelling. The kind of complicatedness in the From Hell Companion is the way my storytelling mind works now. So it's the fiction at the same time as it's the story of the 'making of,' at the same time as it's a dozen arguments technical, philosophical and personal.

Seeing this much behind-the-scenes work is amazing. Do you have a habit of keeping all of this stuff for all of your projects? And how'd you go about getting the other material, from Alan and such?

Yes, I do keep everything, more or less. And as for Alan's sketchbooks, that's a strange one. I didn't even know they existed until Gary Millidge revealed them in his biographical Alan Moore, Storyteller, which is a great book, by the way. And so, after all these years I saw these preparatory sketches that Alan made for all those pages I drew. Some of them are so exactly as I drew them that it's uncanny. Others are quite different because I had other ideas.

To the world at large you're best known as the artist of From Hell, but to me your standout work is Alec. What's it like being so known for From Hell at seemingly the exclusion of your own solo projects?

As an artist I'm always thinking about what has got to be done next, so I don't sit around feeling sorry for myself.

Alec has stood the test of time and become one of the pillars of your bibliography. There’s a bit of you in there, but also a bit of fiction and a bit of imagination in there. But how does doing stories at least tangentially inspired by you effect yourself? Do you think you’d end up different than you are now had you not done semi-autobiographical stories to such a degree?

If all my work was to consumed by a fire except one, I would want it to be the Alec books that was spared. All my thoughts about the art of making comics are bound up in those pages. Everything else exists to justify and shore up that body of work.

Do you think the process of doing Alec was an outlet, psychologically?

You mean as a kind of therapy? I've never understood this idea of art as therapy. The creation of art is a terrifying thing. Not a thing that makes you feel good.

Where do you think you'd be mentally had you not struck upon Alec to get those thoughts and ideas out there?

I think I only had certain thoughts because I put myself in the position to have them. Deciding one is an artist involves committing to a different relationship with stuff. I don't mean this in any highfalutin sense. Deciding to be hired as a night watchman puts one in a different relationship with the stuff in the warehouse.

I really enjoyed the essay you did for The Comics Journal last year on your Rules of Comprehension. What would you say is the No. 1 rule you’ve learned for being a working cartoonist, especially in light of 2012’s The Lovely Horrible Stuff?

My overall rule for making your living as an artist. Claude Monet once said that to paint a picture you must first see it in your head. And I think this also applies to the whole career. You must begin with a concept of what it is to live your life as an artist. That's not to say that you can't make adjustments as you go along. But you can't just stumble through this thing and expect it to come out right by accident.

If that's the case, how did your mental image of what your career would be like match up with where you're at right now?

I am where I always wanted to be, but the comics medium is still ass-backwards. I would have wished it to have advanced differently. In my ideal universe the superhero would have disappeared by now. An intelligent world would have realized that this wish-fulfillment fantasy is absurd and would have rejected it. Instead it has been glorified and is now the foundation of the film industry.

You’re best known for creating and co-creating your own characters and working in your own worlds, but on the rare occasion you do some work-for-hire. I remember Hellblazer, but also 2004’s Captain America issues you’ve done. What is your perspective on doing that kind of work?

My first thought would be to say these are examples of not sticking to the plan. I didn't go looking for any of these things. they all arrived by accident. But I used to have another rule about not turning down any work that comes along. One day you'll be without work and you'll be cursing yourself for all the ones you turned away.

So after they were finished, was it merely a good paycheck or do you think doing those affected the work you do for yourself?

It was just a momentary thing. If it provided an anecdote or two then it was worth doing.

You’ve been working in comics for a while now, and have seen a lot in comics. What interests you these days about the medium and about the works coming out?

I don't really follow what's coming out. The medium didn't go quite the way I wanted it to go and I stopped paying attention. My interest in comics and cartooning tends to lead me into the backstreets of history. There are a few exceptions, of course: Chris Ware, for one. A new book by Ware will have me rushing into town to get my copy.

The backstreets of history are just as interesting as the modern main-street affairs. What material are you digging into from the past as of recent?

The world of any era, present or past, is only interesting to me when you get behind the facade, the pretense of what life is really supposed to be about. The main streets of history interest me no more than the main streets of today. The real story is always happening elsewhere. Nothing is what it at first seems to be.