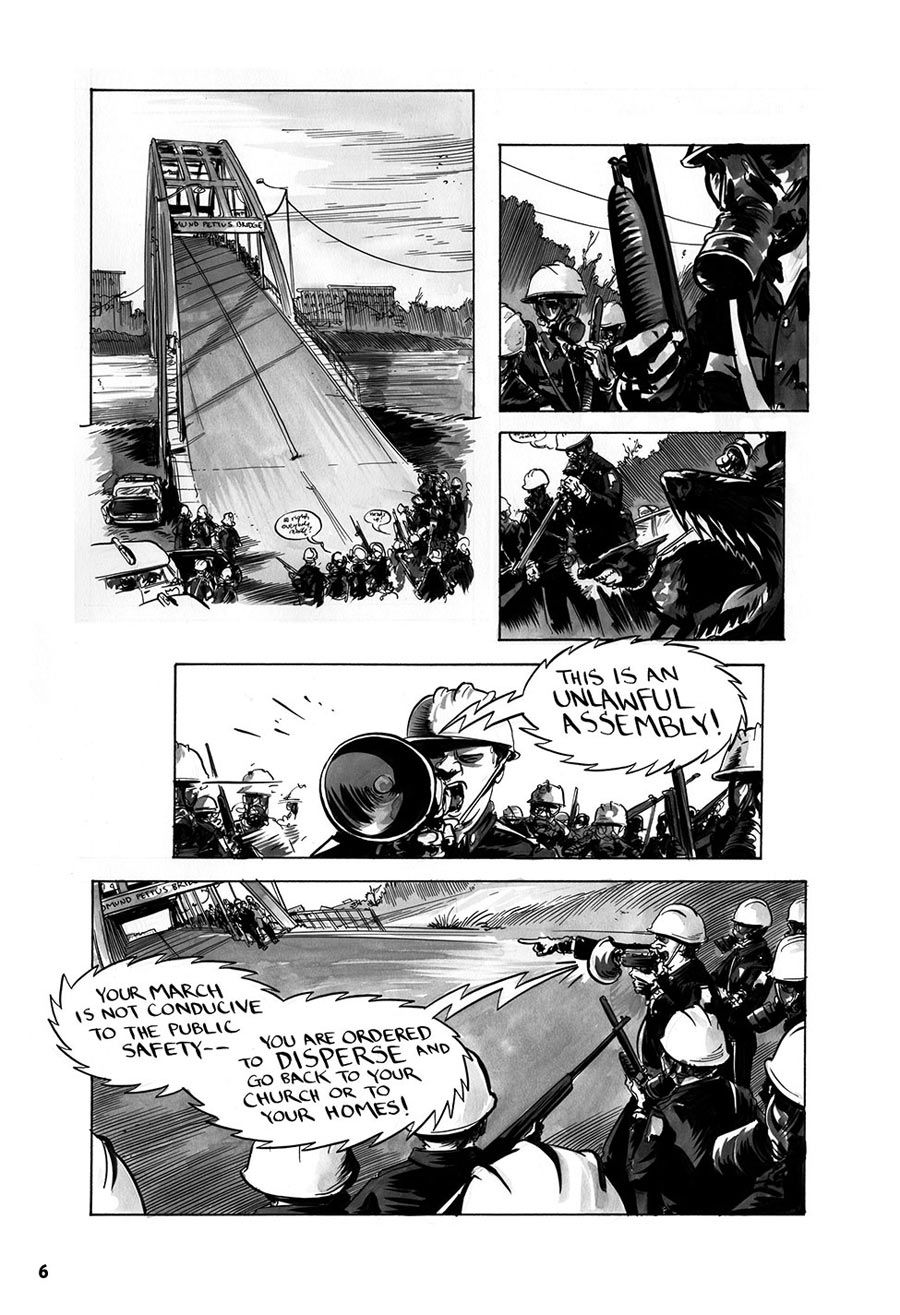

When the Edmund Pettus Bridge was named a National Historic Landmark earlier this year, it was not because of its construction or design. Rather, it was because of what happened on that bridge March 7, 1965, a day that became known as "Bloody Sunday" and represented both the best and the worst of humanity.

The March from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama occurred months after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. received the Nobel Peace Prize and a decade after the Brown v. Board of Education decision was handed down, a time when African-Americans were often denied the right to register to vote. The peaceful protest, led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams is, along with Gandhi's 1930 March to the Sea, considered one of the great acts of nonviolent resistance. Of course, while the protestors were nonviolent, they were met by violence.

Eight days after the march, President Lyndon Johnson convened a joint session of Congress to introduce the Voting Rights Act. In that speech, Johnson used much of the same language Civil Rights protestors had been using for years, even closing his speech with the phrase, "We shall overcome."

"At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man's unending search for freedom," said President Johnson. "So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama."

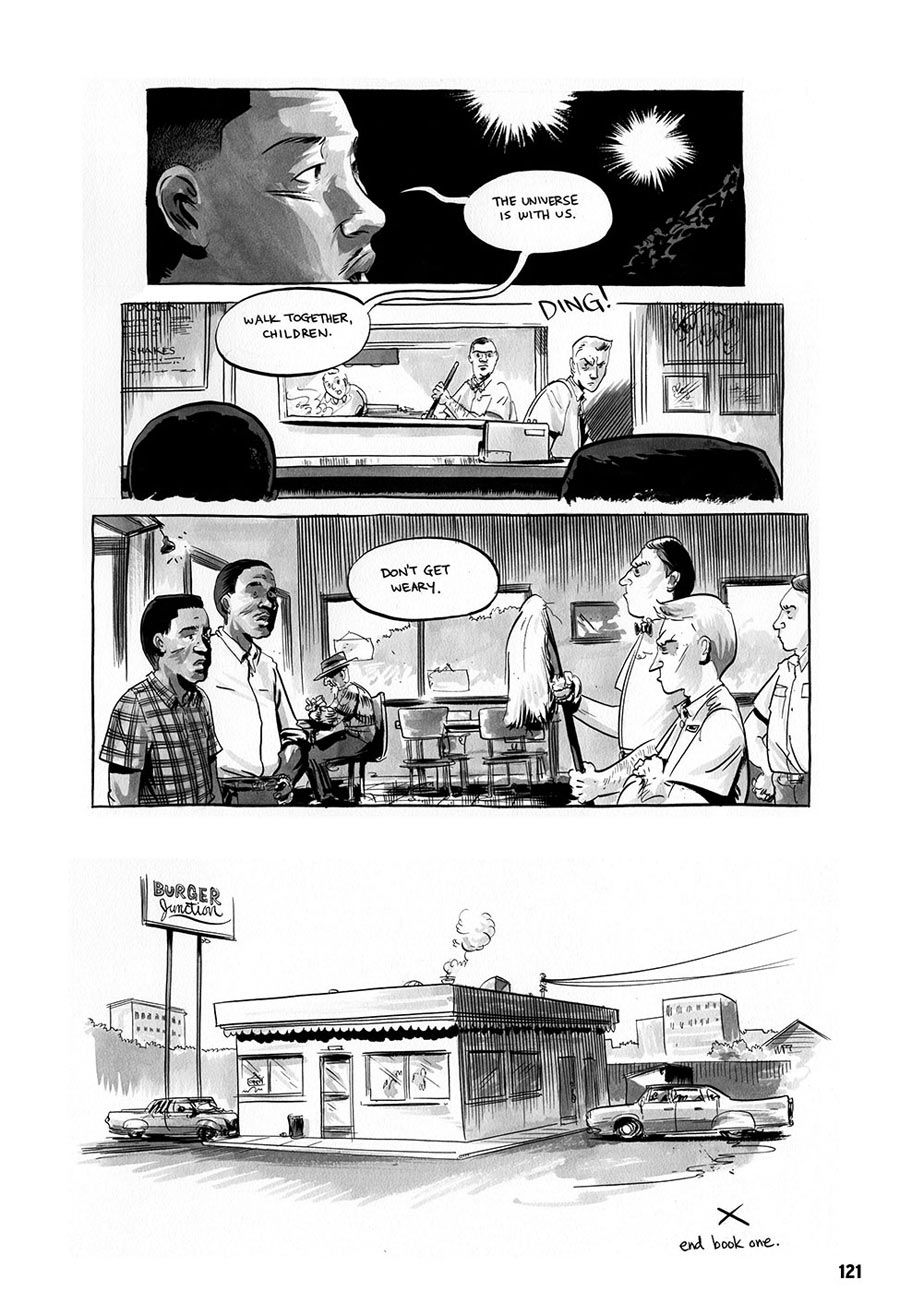

In August, Top Shelf Productions is releasing "March: Book One," the first volume of a trilogy telling the life story of John Lewis, the U.S. Representative from Georgia's 5th District. In the graphic novel, drawn by Nate Powell and co-written by Andrew Aydin, the Congressman takes readers over that bridge "from a past of clenched fists into a future of outstretched hands," in the words of Former President Bill Clinton. CBR News recently had the pleasure of talking with Congressman Lewis about his experiences in the Civil Rights Movement and turning those experiences into one of the most anticipated comics of the year.

I.

Asked how a sitting member of the United States House of Representatives and recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom came to write a graphic novel, John Lewis gestured to his aide, Andrew Aydin. "This young man is the one that came to me and said that we should do a comic book. The rest is history."

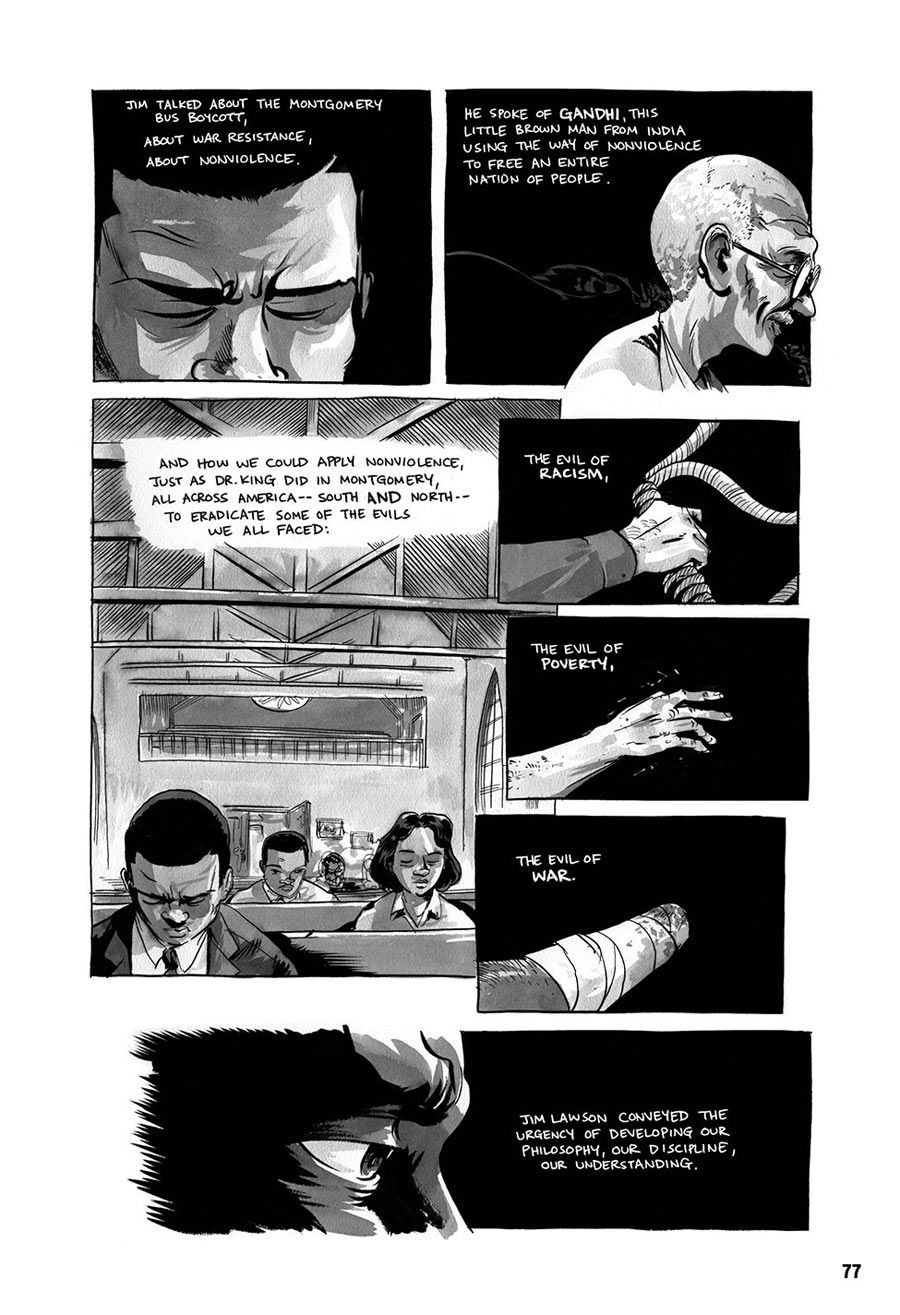

Aydin said that it all began in 2008 when it came out that he attended a few comic conventions. "When you say that openly in politics, people tend to tease you," Aydin laughed. "The Congressman very thoughtfully one day turned around and said, you know, there was a comic book during the Civil Rights Movement and it was incredibly influential." That book, "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story," which told the story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, was published by a pacifist group, the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR).

It also later became the subject of Aydin's graduate thesis. "After the bus boycotts were over, they really wanted to find a way to get that story to young people to show them that nonviolence works, that there is a way to protest segregation and things that you find unjust in your community," Aydin explained. The comic helped inspire a young man in Greensboro, North Carolina named Ezell Blair to stage a sit-in to protest segregation. Blair was one of the group who became known as the Greensboro Four, the spark that launched the student protest movement through the South.

"Then you find out that it ended up in South America, South Africa, Vietnam. Most recently it was translated into Arabic and Farsi and was distributed in Egypt." Aydin still seems a little amazed as he reels off the languages the book is available in, the countries where it has been used as a tool for organizing and educating people. "That a comic book could have that sort of impact; could be directly responsible for social change, for people being willing to put their lives on the line for what they believe in -- to me, as a lifelong comic book fan -- was this unbelievable thing.

"I was young enough where I probably didn't know better to turn around say, Congressman, that's just the Montgomery Bus Boycott, what about the rest of the movement? You need to tell that story," Aydin continued, pausing to take a breath. "I think he showed a lot of faith and trust to say to a twenty-four year old, yes, I will do that -- but only if you write it with me."

II.

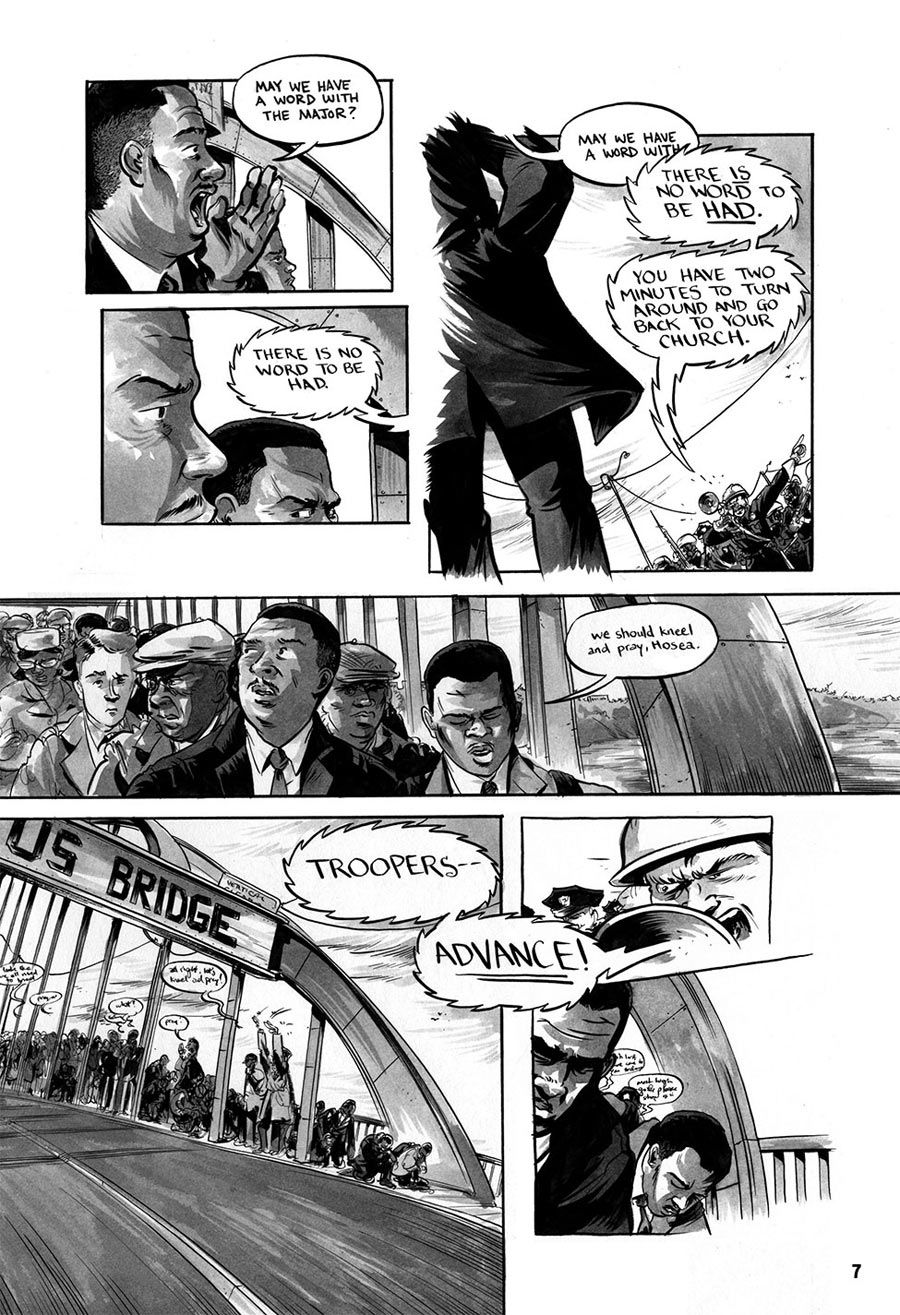

In 1958, the FOR appointed a young man named Jim Lawson as field secretary for the South and sent him to Nashville, Tennessee. Lawson had refused to report for the draft during the Korean War as a matter of conscience, spending a year in prison for his protest before working as a missionary in India. After returning to the United States, he met Dr. King who encouraged him to go to the South. In Nashville, he began a series of workshops in the basement of the First Baptist Church, teaching the history and practice of nonviolence. Among that group composed primarily of teenagers was a young John Lewis, then a student at American Baptist Theological Seminary.

"You're talking about a saint," Lewis said when Lawson's name was mentioned. "Every Tuesday night, he literally poured out his soul to a group of us young people. Under him, we studied what Gandhi attempted to do in South Africa, what he accomplished in India. We studied Thoreau and Civil Disobedience. We studied the great religions of the world. We talked about what Martin Luther King Jr. was all about in Montgomery."

Perhaps one of the most striking moments in "March" is what the students went through to prepare to protest. Today before a protest, organizers will often suggest items of clothing not to wear, what to bring, things to prepare for -- all of which pale in comparison to what Lewis and his fellow protestors met. The students in Nashville knew they would meet resistance, be harassed and face violence, and they prepared accordingly. "It was trying to see could we discipline ourselves to someone calling us names or someone pretending they were spitting on us or pouring hot water on us-we would pour cold water on someone," Lewis said. "We were sitting at a table pretending it was a lunch counter and someone would pull the chair out from under you. Could you take it if someone would blow smoke in your face? Going through that with Jim Lawson strengthened us."

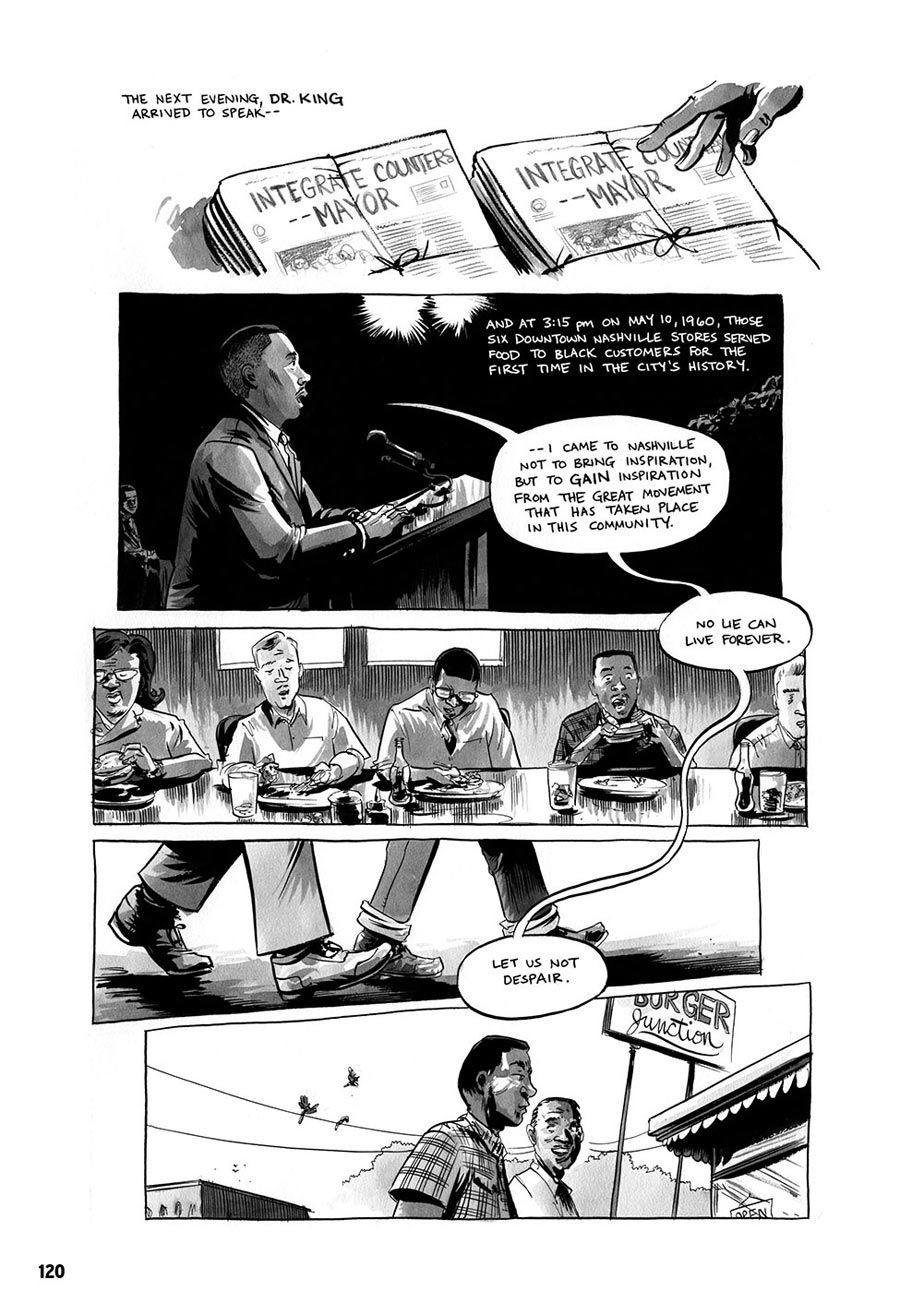

"We became what we called in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a circle of trust. A band of brothers and sisters," Lewis continued. "When we left those workshops with Jim Lawson, we were ready to face hellfire. We were ready to literally put our bodies on the line. We were committed to do everything possible to end segregation and racial discrimination in the American South. Jim Lawson was the first one to talk about the beloved community to us. To talk about redeeming the soul of America, as Dr. King picked up later. He also picked up the beloved community. It was in Nashville under the leadership of Jim Lawson that Dr. King would come and say that the Nashville movement was the most disciplined, most committed movement of any place that he had visited in the South, and it was due to Jim Lawson."

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) grew out of the student-led protest movement across the South. The core of SNCC was many of the Nashville activists including Diane Nash, Marion Barry, Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel and many others. Members of the SNCC put their lives on the line numerous times in the Freedom Rides, during Mississippi Freedom Summer, in Selma and Birmingham and through the region in the years that followed.

In multiple books about and accounts of the Civil Rights Movement, people mention that Lewis' status as a leader and one of the reasons why he was President of the SNCC for years was due to the strength of his convictions. Lewis gave speeches -- most famously at the 1963 March on Washington -- and some of his classmates remember the sermons he wrote and delivered while at seminary decades later, but he was not known as an eloquent speaker. His stature -- then and now -- stems from a moral authority and a passion that is evident to anyone spending any amount of time with him.

Aydin called Lewis "a radical for love," a phrase that brings to mind Dr. King's "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," which was written in part as a response to white ministers who condemned the protests and called King an extremist. "Though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter, I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love," King wrote, citing Amos and Paul, Martin Luther and John Bunyan, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln as similarly radical figures. "So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice?...Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists."

III.

Aydin has been working for Congressman Lewis for years and may have been the impetus for "March," but he still apears a bit overwhelmed when talking about the book. "Looking back on it, approaching him with something like this is a reflection of both his radicalism and his ability to have insight where others may not. Because for him to say yes to this, that's something else. No other member of Congress would do this," Aydin said, adding, "I don't think any other member of Congress has a story to tell like he does."

The structure of the book, the way that it unfolds in this volume and how they've planned for it to unfold over the course of the trilogy, is something Aydin and Powell worked long and hard on. "It's a great story in and of itself, but how do you tell it in a way that takes advantage of the comics medium, not just uses it. There's an advantage to telling stories in comics," Aydin said mentioning Art Spiegelman's "Maus" as a book he always had in the back of his mind as a model. "The only thing that that we used as a narrative device is the single mother and the two children, because there were several people in the office that morning."

Nate Powell was recruited to illustrate the book thanks to his longtime relationship with Top Shelf and Publisher Chris Staros. "I was aware of John Lewis, but I wasn't aware of the extent of his legacy and his work," Powell told CBR, speaking by phone from his home in Indiana. "I was just amazed that not only was this guy at the forefront of so many parts of those movements, but that he had never stopped fighting the good fight. He was one of those people who kept his head down and kept on doing the work."

Powell compared some of the challenges in "March" to an earlier book he drew, "The Silence of Our Friends," a story about Civil Rights protests in Houston in the late 1960s. But with this project, he faced challenges he's never encountered before. "In 'March,' you're dealing with dozens and dozens of people who really existed, many of whom are still alive today. There's that issue of faithfulness and accuracy -- which is not exactly the same thing," said Powell, explaining the amount of research involved in order to accurately depict every aspect of the script.

"Working through the script, the other challenge was on the opposite end," Powell continued. "The fact that there was so much information to convey and to be faithful to, I had to remind myself that there were these very personal and internal and silent moments happening within the script -- some of which were implicit. It was my job to locate them and dig them out. Moments of tension, anxiety, fear, love; learning when to tease those out of the script and learning which parts of the script to expand to get into the intimacy of this personal experience as well as the fact that this was a much larger social upheaval."

The first book ends after the Nashville sit-ins reached their climax and the city's lunch counters were desegregated. Powell is currently drawing the second volume while Aydin is working on the script for the third, both saying repeatedly that the next two books are different from the first. "This theme in the first book is beginning -- the beginning of the day, the beginning of the movement, growing up, youth -- and the theme for the second book is enduring. It's managing to survive. It's going through this day," Aydin said. The second book will detail the events of the 2009 Inauguration as seen by the Congressman, but it is a much darker volume.

"The violence really escalated after the sit-in movement," Aydin said. "You have a period of time when they had stand in protests in front of movie theaters. Then we get into the Freedom Rides, John Lewis becoming chairman of SNCC, the movement in Birmingham in 1963, sort of climaxing with the March on Washington." Aydin hesitates, trying to find the right phrasing. "The March on Washington was a great moment, but it was an activist moment. Nothing concrete was accomplished. When you walk away from that, eighteen days later, four little schoolgirls were killed in the bombing in Birmingham. That's where we end it."

Upon mention of the violence unleashed against protesters, Powell said, "It's real dictionary definition terrorism. It's domestic terrorism against American citizens.

"That four years before my brother was born, black Americans were being beaten in the streets by uniformed government employees in broad daylight under orders of the city or the state seems unreal," Powell told CBR News. "I was a little worried going into it that this might seem a little too smooth compared to the reality, but there are a lot of moments where I have to draw some really brutal stuff in Book Two.

"What's really surprised me about 'March' is the fact that it shocked me even as I'm drawing it, even though I'm very familiar with the subject matter and the historical context already."

"There is something to be said, that you would have somebody from Arkansas and somebody from Georgia from another generation working with Congressman Lewis. I think the fact that the collaboration even occurred is a source of hope. I think it shows the measure of the distance traveled," Aydin said.

"I feel like I was very well prepared to tackle this project by doing 'The Silence of Our Friends' and doing a couple short stories around the same time," said Powell who grew up in Arkansas, Alabama and Mississippi. "When I was five years-old, my family and I happened to witness a high noon, fully-costumed Klan circle with a burning cross in a small town outside of Anniston, Alabama. I may be part of the last generation of Americans who saw stuff like that out in broad daylight, but it is something that was still happening in the Reagan era. Growing up in the South, most of us are taught to believe, and do believe, that the South is the racist backwards part of the United States. I certainly believed that."

Powell paused before continuing. "It wasn't until I settled down here in Indiana that I realized that most parts of the Midwestern North are far more racist than anywhere I lived in the South. A lot of it has to do, I think, with this attitude that, at least we're not the South. And it has to do with the sheer homogeneity of the people's environment. People don't have to deal with people who aren't just like them. The racism up here is a lot more fear-driven, anxiety-driven.

"There are times when I'm drawing where I'll be amazed at how much our society had changed in the twenty years, fifteen years before I was born that it does seem like a completely different country. I remember having that feeling when I was a kid, talking to my parents about what life was like in segregated Mississippi. That it really did seem like a different land altogether," Powell said. "In equal measure, what's more disturbing is when having to depict certain things, being able to draw on my own memory as a kid for certain events and certain occurrences, throughout 'March' and 'The Silence of Our Friends.' I'll realize that absolutely nothing has changed in some ways.

"This is an unclouded glimpse into one person's direct experience of brutality, terror and hatred, but basically having faith in the goodness of the people around him to persevere -- and knowing that it did," Powell continued, admitting that when illustrating the books, some days are a lot harder than others. "I had to stop after one panel for the day because the necessity of accurately drawing Emmett Till's dead body based on the crime scene photos of when he was pulled out of the river. I had to just call it a day."

IV.

"Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story," a comic which has been translated into different languages around the world, inspired "March"

"People ask me sometimes," Lewis said, "'You did this and you did that and how did you do it?' I say, the only thing I did was I gave a little blood. Other people gave their very lives."

Lewis comes to life when talking about others in a way he does not when discussing himself. It's easy to picture him as the minister he once sought to become. "As we move along with the other volumes, we're going to talk about the young people that died," Lewis said. "Andrew said earlier that the movement was nonviolent. We practiced the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence, but there was a lot of violence. There were people who were beaten, shot and killed. I tell young people that before you were even a dream, before you were even born, three young men that I knew, three young men, two from New York City, Andrew Goodman and Mickey Schwerner, and James Chaney, a young man from Mississippi, were stopped on June 21, 1964 in Philadelphia, Mississippi by the sheriff, taken to jail, taken out of jail, turned over to the Klan where they were beaten, shot and killed. These three young men didn't die in Vietnam or in the Middle East or Africa or Central or South America. They died right in their own country. Young people need to understand that. What happened and how it happened."

I asked Lewis about his education as a young seminary student and Reinhold Niebuhr -- whom President Obama has cited as his favorite philosopher -- a theologian Lewis studied then who abandoned the philosophy of nonviolence. Those are the words I used, but I was asking the Congressman the same question he's been asked for decades: In the face of everything, how has he maintained his belief in nonviolence?

"I happen to believe that, as Jim Lawson taught us and as Gandhi said, it is nonviolence or nonexistence," Lewis answered. "Dr. King said on one occasion, we must learn to live together as brothers and sisters, or we will perish as fools. I just believe that we must respect the dignity and worth of every human being, and in every human being, there is a spark of the divine. We don't have a right to abuse it. For me, nonviolence is one of those immutable principles that you cannot give up on, you cannot deviate from. For if you turn to violence, you're saying in effect that there is little hope, that you're giving up. If you're going to redeem the souls of individuals, if you're going to redeem the soul of a country, if you're going to make the world a world at peace with itself, there must be an end to conflict; there must be an end to violence."

While it's not difficult for Lewis to revisit those places and those memories, he says that he does become emotional sometimes. "To go back to a place like Selma or Montgomery and see the changes. To see the young police officer who's now the chief of Montgomery walk up, come to a meeting to speak and say, 'Mr. Lewis. in 1961 we didn't protect you. We didn't protect the Freedom Riders. We allowed the Klan and the mobs to beat you.' Then he turned around and said, 'Will you forgive us?' And in order to show what we did was wrong, he said, 'I want to take off my badge and present it to you.' I said, chief, you can't do that, you need your badge. He said, 'I can get another one.'

"Many members of the House, several members of the Senate were there and a lot of community people -- the church was packed -- and they just started crying," Lewis recalled. "One of the people that beat me and my seat mate during the Freedom Rides in May 1961 came to my office after Obama had been inaugurated in February '09, with his son, and said, 'I'm one of the people that beat you, will you forgive me? I want to apologize.' He started crying, his son started crying, I started crying. He hugged me, I hugged him back and they both called me brother."

Leaning forward, Lewis said, "You see signs of people coming together and being reconciled. You can't give up. You can't give in. I tell young people, don't lose hope. Don't become bitter. Don't get lost in a sea of despair. Hopefully at the end of these three volumes there will be a message of hope in spite of the violence, in spite of the setbacks and the disappointments. That's why I cried so much when Obama was elected. Someone said to me, we saw you crying so much the night of the election, what are you going to do when he's inaugurated. I said, if I have any tears left, I'm going to cry some more, and that's what I did."

Like many, the popular uprisings and nonviolent protest movements in recent years across the Middle East and elsewhere have affected Lewis. "I have a tremendous amount of hope when I see young people and people not so young standing up, resisting, in a peaceful, nonviolent fashion," the Congressman said. "The power of people. The power of an idea. People thirsting for freedom, to be human." He paused, as if recalling a specific memory. "That is very inspiring. They give me hope."

Thinking about Lewis' life and work, I was reminded of the original speech he planned to deliver at the 1963 March on Washington which included the line "We shall fragment the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together in the image of democracy." When Lewis was a child, his parents could not register to vote and now he is a legislator in a nation with an African-American President. He has helped to transform America into a more perfect Union -- "in the image of democracy" -- to such a degree that, two generations later, we can marvel at how much it has changed. Lewis has spent his entire life in service to the idea that not only can individuals change the world, but that art -- that a comic book -- can change the world.

"I hope the book will make it plain, make it simple, as Martin Luther King's father used to say," Lewis said. "We called him Daddy King, and when Dr. King Jr. was preaching, sometimes [Daddy King] would say, 'Make it plain, son, make it simple.' I hope 'March' will make it plain."

"March: Book One" will be released by Top Shelf on August 13. Congressman Lewis will be on Comedy Central's "The Colbert Report" that night to discuss the book. He will also be making appearances at the American Library Association Annual Conference June 29, Comic-Con International in San Diego in July and the National Conference of African American Librarians in August.

For more information, or to download the book's free teacher's guide, go to: http://www.topshelfcomix.com/catalog/march/760

EDITOR: This interview has been updated with the proper location of the cross burning Nate Powell saw as a child.