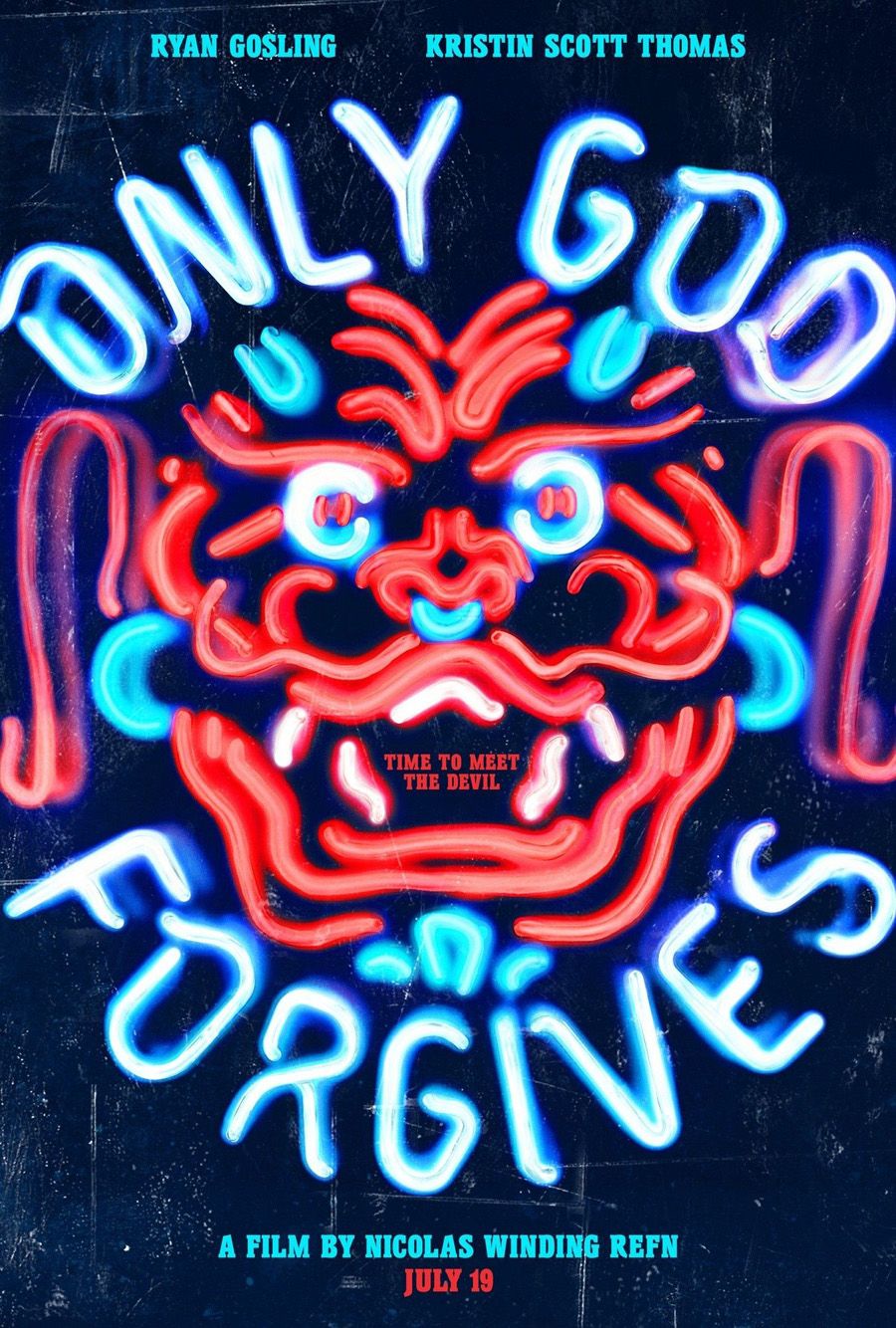

Although just a few years ago he was probably best known as a frequent collaborator of Steven Soderbergh, Cliff Martinez has become one of the premier composers in modern Hollywood. His work on Soderbergh’s Contagion and Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive catapulted him into a different strata, thanks not only to the distinctiveness of those works from the rest of what Hollywood was producing, but their uniqueness in comparison to each other. Subsequently, his work on Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers, and now, Refn’s Only God Forgives are making the same sorts of waves, as he changes the musical backdrop for storytelling even while he challenges himself to think outside of his own comfort zone.

Spinoff Online recently sat down with Martinez to discuss his ongoing collaboration with Refn, and the differences between the Only God Forgives score and his work on Drive. Additionally, he talked about avoiding the trappings of typecasting, and offered a few hints about upcoming projects – including Refn’s Barbarella -- that promise to further challenge him as he expands his repertoire.

Spinoff Online: When we spoke about your work on Drive, you talked about how temp scores are often a very valuable tool for you as a composer.

Cliff Martinze: Yes, I’ve changed my opinion on that since then.

Really?

I’ve always thought of them as a great communication tool, because music is a slippery, ethereal thing to talk about, or an abstract thing. And temp scores have always been very helpful. But occasionally, not naming names, but they can marinate in a rough cut for too long and they can go through preview screenings and then people get attached to it – and then the process becomes more difficult because you’re trying to dislodge something that is well-liked. It happens rarely, but when it happens it is pure evil, and now I understand why some composers have an aversion to even hearing one or using one. I was talking to the guy that does Breaking Bad, who was a new composer at the time that he was brought onto that show. And he said, “I have one rule – no temp score. No temp score for me, no temp score for you. You cannot cut the show with a temp score; I don’t want anybody to have a temp score.” I thought, well, I admire your testicles, sir (laughs).

When Nicolas was making the movie, he said he wanted the soundtrack to be comprised of Thai country-and-Western music. Although he seems to have at least partially pulled that off, there also seems to be a heavy classical influence – Wagner, Ligeti. What did you want to draw upon as you were assembling the musical backdrop for the film?

Well, the Thai thing was something I wanted to keep in there, and there’s a residue – and people have pointed it out. The foundation of the film was built, like Drive, on the songs. I did five songs, like, five Thai karaoke songs, and I thought the film really needed that – or I thought it would be more entertaining musically for me to draw something from Thailand and try to put that into the music. So after doing the Thai karaoke songs, I sort of had an idea of what constituted the Thai sound, and then I went to Thailand and barricaded myself in a hotel room for five weeks. I actually never left the room, because the schedule was so intense. But I tried really hard to bring the musical culture, the musical world of Thailand into the score. And just as usual, I aim here and ended up over there somewhere. But I did have a Thai folk instrument called a pin – a three-stringed electrical lute that was popular in this northeastern Isan Thai music or as the rest of Thailand thinks of it, it’s country, or maybe even hillbilly. I mean, a lot of people didn’t even like that music —

A bluegrass or folk kind of music?

Well, the reaction you got from some people was enormously popular. Like a lot of music of the world, the underclass generates the great food and the great dances and the great music. Isan, which is like a third of the country, really, just the rural northeast kind of farming sort of center of Thailand. That’s where all of this Isan music comes from. Now, it doesn’t resemble our country-and-Western music in the slightest – it’s electrified, a lot of it’s like pounding party music – and then they’ve got the really syrupy ballads too. It’s mostly like celebratory music; Nic knows more about the lyrical content. I have a blind spot for lyrics, and I don’t speak much Thai. But he had translators, so I don’t know what the music is about, really, but it sounds like celebratory party music; I went to a few concerts of Isan music, and it’s definitely party stuff, people falling down drunk. At least, that’s what it is for me. So I had sent Nicolas – initially, he was interested in Western country music, and wanted to have Thai actors singing “Ring of Fire” and stuff like that. I think when he thought about the price tag – because they would have had to be iconic songs, because if a Thai actor sings an obscure American Western song, it would have made no sense. So it had to be “Country Roads” or a Dolly Parton song for it to be something people would know. And I sent him some of my greatest hits from Isan, and said I love this music. I haven’t heard a lot of music in Thailand, but this type of music, I really love it. So I think that’s when that kind of got in there. So that was the first thing I did musically, and I wanted to carry the Thai thing further, but kind of Bernard Herrmann got in there and Phillip Glass and Brian Eno and the usual suspects. But there’s a remnant of Thai in there that I think contributes to whatever kind of music you think it is. There’s a little bit of that in there still.

Although there are certainly similarities to your work on Drive and Spring Breakers, this feels like it uses more live instrumentation. How did you decide on that, and how did you figure out the sort of melodramatic quality that this has in comparison to those previous scores?

Your observation about analog probably comes from the fact that it was on a low budget, and through the miracle of computer technology, we tried to make it orchestral. That idea came from Nicolas’ temp score – he used The Day the Earth Stood Still, the 1951 version with Bernard Herrmann, which is my favorite score of all time. So even though I thought it’s not really 100-percent appropriate, I love that music so much that I’m all over it. So I tried to find a way to get the sci-fi ‘50s Bernard Herrmann thing in there; it was an otherworldly quality that I thought made sense. The Wagnerian thing, which is one of the people that I think Herrmann stole from, was in there for some of the romantic moments, and that was the thing that I thought was different for me – when people want to do an orchestral score, I’m usually not on that short list. But after Nicolas started cutting, he just fell in love with that score. So that’s where the notion of the orchestra came from. And then there’s actually a real orchestra for the love theme; the main line was recorded by the Bratislava [orchestra], but we didn’t have the money to do an orchestra for the whole thing. So the rest is all samplers and fake orchestra, though I tried to make all of it sound authentic and believable.

Nicolas said he wanted to use that love theme for the scene of intimacy between Julian and the prostitute, and then again in one with Julian and his mother Crystal. How much do you participate in that decision-making process – to use it in two dramatically different contexts?

He took credit for that? (laughs)

He said he used it. I don’t want to get him in trouble – he didn’t claim to come up with that idea.

Hm, I’m trying to think. I think we both thought that the film needed some emotional core – it needed some warmth and some emotion, and the music might be the best-suited character to deliver that. Because everybody is a little bit mean and stoic and noncommunicative. So I liked the idea of a love them, and once it was on the table, it was a great theme, and it was one of the things that could actually bring a tear to your eye. But it was like, OK, what do we do with it? The closest thing we have to a love scene is a girl masturbating and a guy lighting his mom’s cigarette. So we kind of shoe-horned it into places that were kind of unexpected, but that’s what I kind of liked. Last night I mentioned that I had not expected to use at the very end; I had not thought of that. I know Nicolas thought that up, because the thing with the mom, I think we both talked about, like, hmm, this guy’s relationship with his girlfriend, his mom is probably more like his girlfriend than his girlfriend, so let’s use it on the mom. So I think that came out early on, but in the final mix, either it’s here or when the hands are cut off, and I just thought, why did he throw out the thing I did for – Ohh! That is an intimate moment, isn't it? So it was interesting, and that’s what I find fascinating, is that once music’s written, you intend it for one thing, but really the music has a mind of its own with where things go. And it might dictate things that are unexpected – and that was certainly unexpected for me. But in hindsight, I was going, yeah, okay, the love theme over [a climactic scene]? Sure, I can dig it. It make perfect sense.

There’s a tableau quality to Nicolas’ recent films where he seems almost to use the actors as mannequins where he projects emotions onto them with the music. Does that give you a great sense of creative freedom or does it challenge you with a certain responsibility?

Yeah. Sure, it complicates things, in that you’ve got to burn a few more calories than you normally would, so yes, there’s a bigger responsibility, but it’s one I kind of welcome. But the interesting thing is that Nicolas and I both like music that is minimalist, that doesn’t spoon-feed the audience the response that they’re supposed to have. And he wanted these guys to be ambiguous. But he likes that in the music too, which kind of makes it even harder – because you don’t want to spell it all out. So the music tended to be a little bit more about the situation than it was about the characters and explaining who they were and what they were feeling. He wanted them to be Mona Lisa-like, and ambiguous, so even though there’s a lot of real estate to be covered by music, I don’t feel like I was ever talking down to the audience. The word that has been coming up in all of these Q&As, I don’t know who came up with it first, but it is installation – it’s more like you observe, it’s a sensual thing where it looks great, it sounds great, but what does it mean? We’re not sure. So I think the music wanted to maintain that quality, and certainly it was a fat, juicy role for the composer – and a challenge that I welcomed. And I think I also want to keep things a little ambiguous and allow people to read into it as with Soderbergh, leave a small. dramatic footprint.

Nicolas talks a lot about wanting to change directions with each film he takes on. How much does that force you to fall into creative lockstep with him? Did you feel like this was an easy transition from you work with him on Drive, for example?

Well, it’s a big challenge, because he did say right off the bat that this is not Only Drive Forgives. This is going to be something new – we don’t want any reference to Drive whatsoever. And I think when you have guys like Nicolas and Ryan Gosling and myself, who have strong artistic personalities, we really can’t shed our skin 100 percent and reinvent ourselves completely. I don't think Nicolas did it either; I mean, we saw people not talking very much in Drive, well, mostly one guy, and we have three people in this film not talking. And the violence that kind of really rubs our nose in it, I think there are a lot of hallmark signature flourishes that you see in this film that you saw in Drive. But I’m kind of proud of this, because the orchestral thing, I don’t do that well. I certainly don’t do the car-movie type orchestral stuff – I can’t remember the last time I did anything like that. So I think I did a good job of coming up with something fresh and new; the ingredients were new – the Thai thing, the Bernard Herrmann thing. The Phillip Glass thing, been there, done that, the ambient Eno-esque dark, textural stuff, that wasn’t really a step in a different direction. But when I get into these things, I feel like I’m looking at the Empire State Building with my nose up against it; I don’t have that much objectivity about it. Now that I’m done with it, I kind of see that the smoke has cleared, and it feels like a straight ahead horror score to me when I listen to it by itself – which is interesting, because I don’t see the film as a horror film. But so far, people that have come up to me have been like, wow, how come you didn’t do Drive again? Why doesn’t it sound it sound like Contagion, either? So I think I did something new, I think Nicolas did something pretty new; I think if he wanted to make a left turn and do something unexpected, I think he succeeded. But if he’s going to do it again, he’s going to have to do a film where everybody talks too much, and it’s a comedy.

How much do you worry or think about becoming too identifiable with one particular style or sound?

I think I worry about being typecast for doing one type of film. I think that happens to all of us – anybody who does a good job with comedy has a career in comedy, but at the price of nobody ever considering you to do a drama. So I think I kind of have been cast as the Prince of Darkness – like, if you have a movie that has drugs and has people getting stabbed and blown up, then I’m your guy. And I think all of us like to try to stretch, but we’re afraid to stretch a lot. So my next film is going to be a straight ahead revenge thing more in the vein of like Taken or Die Hard, without gigantic effects. So I’ve never really done a full-blown action film, so I welcome that challenge. But I like to reinvent myself in baby steps, so I do worry about it, and I have passed on things that really sound like ‘We just want you to do Traffic – don’t get clever.’ And I’ll just say, no, thank you.

What’s the name of that film?

It’s called Mea Culpa. It’s a French film, Gaumont is involved. My experience with the French – I don’t want to generalize, because it’s only two films and two directors, but they just treat me like Elvis Presley. Here I feel like a bricklayer, and there you feel like you’re Paul McCartney in 1965. It’s just unbelievable – well, they take film really seriously. When I was at Cannes, my cab driver dropped me off at the theater, and said, “Thank you for the music.” You know who I am? It was like, this is another planet! So I’m kind of looking forward to it, but it is going to be in French, but Sony is going to distribute it in North America. But I’m hoping it’s a successful film – it’s got Gaumont and some good distributors behind it. I don’t know the actors are; I’m told they’re like big French actors, but I don’t know who they are. But I love that fact that they never choose glamorous people: the lead actor is an older guy, a bad ass kind of in the vein of Taken or something. He’s an older guy that looks like a regular person, and the situations are ridiculously not normal – very extraordinary circumstances. But the actors are all very matter of fact. And there’s a French element to it, that everything is very matter of fact and documentary like. So for me, that’s the next project. Fred Cavaye is the director, he’s done a couple of films, and that’s where I’m going next.

Do you foresee a long-term creative partnership with Nicolas?

It could happen – I mean, so far, so good. Monogamy has its benefits, and he seems to enjoy the relationship. I certainly enjoy working with him. And I told him I would follow him anywhere on any project, as long as it’s not a romantic vampire movie (laughs). So if he can live with those rules, I’ll be his guide. But, yeah, he’s talking about his new project, Barbarella, and it already seems like I’m signed up for that. We’re working on a Grey Goose vodka commercial now, so it seems like there’s a future in working [together]. I think it’s good – I mean, Soderbergh, I’ve been with him exclusively, but I feel you’re able to go deeper; Traffic was so much better than Sex, Lies and Videotape, and then Solaris was even better, and I thought Contagion was just great. So I think having repeat business, as long as you get along, benefits the film. But I’ll be there if he is – and so far it looks good.

It seems like the French film you’re doing could be the connective tissue between Only God Forgives and what will presumably be more action-oriented, and French-originated, with Barbarella.

I know so little about [his version]. I mean, I know what the original is, but I don’t know what his take is on it. And when I’ve tried to pry some information loose, he’s been very cryptic about it. So I don’t know what it’s going to be, except that it’s going to be television, not a feature. He’s decided that he wants to do something where the protagonist is female. And that’s about all I know. So who knows -- maybe Barbarella will be played by Ryan Gosling and won’t have any lines. I have no idea.

Only God Forgives opens Friday