If a cigar can be just a cigar, and not some obvious phallic symbol to be endlessly sucked and played with, then can a superhero ever be just a superhero, or is it always representative of a deeper, more complex need within us?

One of the stand-out moments from the Warren Ellis documentary (Captured Ghosts) previewed in New York last month was when he spoke about his attitude towards the superhero. His voice dripping with disgust and distain, he bemoaned the human desire to look up to something bigger and stronger than oneself. As an unabashed fan of Ellis' work, I would have to say that his attitude towards the superhero has served him well. Without even a bit of hesitation, he takes the genre and turns it all upside down, he is a pioneer in the field of cranky, pissed off superheroes who act more like villains and I love him for it. When they aren't homicidal psychopaths, they're just tired of the game and perfectly content to use every tool at hand to get their way. He's good at creating the kind of dynamics which wouldn't work for a writer more comfortable with our blatant desire for superheroes to look up to, specifically because he wants so badly to make us question that desire.

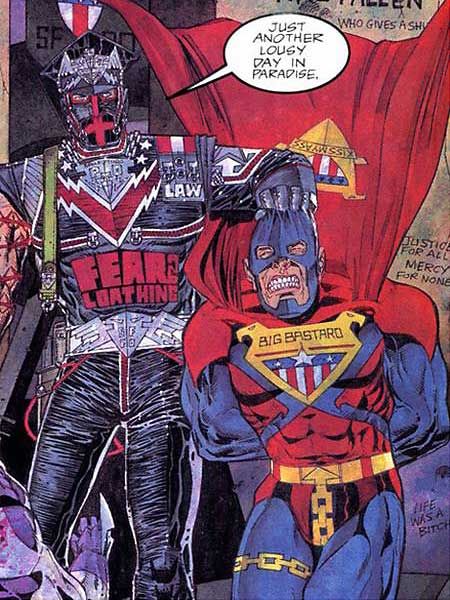

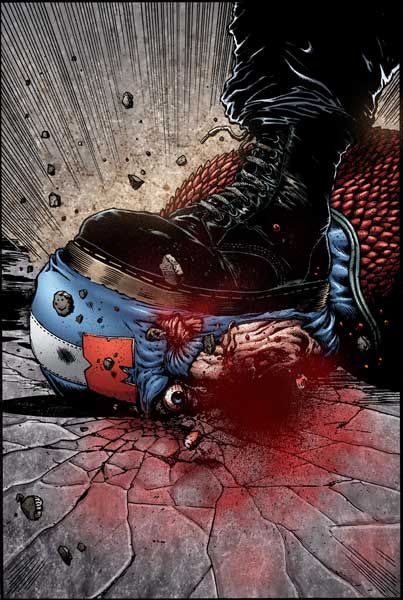

Breathing life into the genre with his irreverent humor exposing the idiosyncrasies of the superheroes he writes, Ellis is part of a now familiar trope; The anti-superhero British comic book writers who grew up in the 1980's. Of course Ellis buries his disdain behind a veneer of rocking, glam-tastic fun in books like No Hero and The Authority, but others have been more overt in their agenda. There was Pat Mills outrageously damning Marshal Law, and Alan Moore's genre-altering, cautionary tale; Watchmen, stemming from his desire to kiss the superhero concept goodnight. Even now, we have Garth Ennis's ongoing series of out-of-control nasty superheroes, watched over and policed by his team of misfits in The Boys. Like all of these writers, Ellis uses his work to highlight the folly of deferring to others simply because we desire a hero so badly.

But where does this desire stem from? and what it is within us which creates this desire for a higher power?

Recently I visited a friend who lives alone. She said that she liked it when I went to bed after her, but she couldn't put her finger on why. We came to the conclusion that it is because it is nice to have someone else turn out the lights and check that the door is locked, since those things are the kind of things we didn't have to worry about when we were children. It is nice to go to sleep, knowing that someone else is on top of things, someone else is taking care of things. It is a holdover from childhood, when we thought that our parents would be able to handle everything and it didn't all fall to us. Of course as we grow up, we are disillusioned and realize that our parents are human and eventually, we move out and we become the adults who have to worry about the mundanities of life.

Wanting someone else to be the adult so that we have someone to defer to is a kind of throwback to childhood. It is understandable, but it is also such a basic, primal desire that we often don't recognize it, which makes it that much easier for others to exploit. By some definitions, religious organizations have been exploiting this desire for aeons, but it is the politicians in recent history who usually take advantage of our unconscious desire for a parental, authority figure.

This where the British satirists I mentioned above come in. These are all writers who came of an age in Britain under the Thatcher government, they are all all men who watched a country's desire for a definitive authority figure become twisted and exploited by their elected government. The eighties was a strange time for the UK in many ways, and people tend to forget that it was an era of "me first" in the wake of the so-called "age of aquarius." Watching capitalism run riot in a country like Britain, previously anchored by all manner of caring, nationally owned resources was shocking for many. Thatcher was the first female prime minister, and she immediately set about proving that she could be more aggressive and stubborn than any male leader. Unlike America, where presidents can only run for two terms, Thatcher ruled for total of nearly 11 years. To many people it felt like she would never let the country go from her iron grip, so it is any wonder that the British comic book writers who matured in that era don't trust people in authority? By extension, the concept of the superhero must look like just another self-declared savior, like Thatcher in her time.

Douglas Adams wrote that no one who actually wants to be president should be allowed to be president, the ego involved in wanting the job disqualifies them from having the humility to do it well. Similarly, anyone who happily puts on a cape and declares them self to be superheroic must be suspect. Writers like Ellis, Moore, Mills, et al do an important job, reminding us that we hold the power to give away, even symbolically, and we must be conscious of who we're giving it to. While their outlook of superheroes might be bleak, their cynicism reminds us to be wary of worshipping a golden calf. Gaudy, empty representations of authority can all too quickly become externalizations of the strength we ought to be looking to find within ourselves.