As regular readers are probably aware, I’ve been a huge fan of Chris Ware’s work for a long time. In recent years I was happy to vote for his books Lint and Building Stories as books of the year, (along with most of the rest of the CBR staff in 2010 and 2012) but that isn’t where my appreciation for him began. Those beautiful books are the culmination of a great body of work, using skills honed over years spent producing a slew of incredible, personal, exploratory comic books. It is in those early comic books that we can see the real roots of Ware’s talent at observing and expressing the breadth of human emotion.

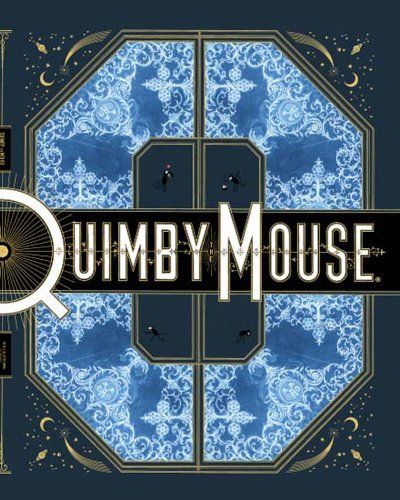

I used to buy the Acme Novelty Library comic books whenever I saw them, simultaneously delighted by the wealth of content contained within and also frustrated by the irregular sizes which made them impossible to shelve in any sensible way. Recently, while moving some books around, the giant hardcover reprint of Ware’s early Quimby the Mouse cartoons popped up because it only fits on one specific shelf with a few other monolithically sized books. I’d forgotten what it was like and so I pulled it down to read it and was immediately thrown back into the familiarly tragic stories of mundane pain and isolated suffering which Ware so skillfully depicted. It has taken me over a decade to realize it, but Ware’s use of irregular sizes means his books stand out from my collection and I appreciate the reminder to reread them.

When I initially read those Quimby the Mouse stories I remember finding them much funnier and sillier than they seem now, and there are a few reasons for that. Partly it is just that I have changed over the years, and so the way I interpret Ware’s metaphors for loss and isolation seem less slapstick and improbably than they did back then. A few years ago I was lucky enough to attend a talk by Chris Ware at the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco where he presented a slide show of his beautiful sketch book and took questions from the audience. He shared this show with Daniel Clowes, who I regarded as similarly talented and assumed that the two might have similar ways of presenting their work. Clowes was as funny and warm as his work, and listening to him talk was relaxing. By contrast, Ware was distressingly self-depricating, to the point where it seemed he genuinely felt guilty for selling us his gorgeous, inventive books. When asked about all of the details and tiny bodies of text he packs in, he spoke of wanting to compensate us for the quality of the work, as if there was something lacking there. It was tragic to hear him put down his wonderful sketches and talk of his loneliness when drawing them, and it suddenly became clear that his cartoons weren’t simple jokes about sad people, but heartfelt expressions of pain.

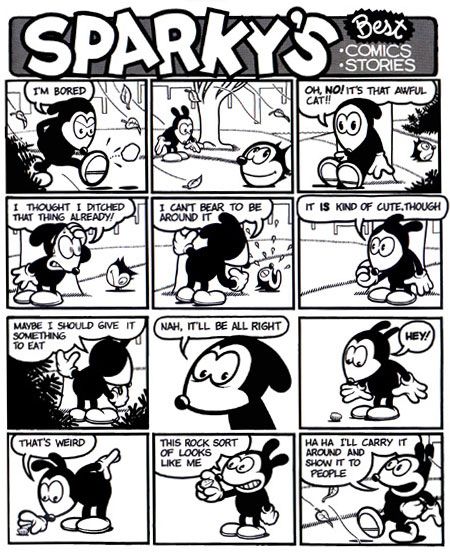

Creating comic books is a pretty intense career choice and many of the authors who write and draw their work seem to have a core obsession which so consumes them that it is central to everything they create, whether they choose it or not. So for example, while an author like Robert Crumb might have sex at the core of all his work, it is the burden of Ware to hold sadness at the core of his work. With books like Lint and Building Stories, Ware has given us glimpses into character's personal lives and their most intimate moments of self-realization. Ware's early work is far more raw, frequently a simple expression he seems to need to get down on paper, not necessarily for the enjoyment of readers or even his own, but apparently simply to record the moment and get it down. In this way his early work is more of a pure expression of an emotion, without guile or artifice. There is often no linear story, but instead a series of increasingly tragic events without any clear end or conclusion. In Chris Ware’s early work, sadness and depression is not spoken of, never described or even examined. It is simply the way the characters exist, a fact of life, an inescapable aspect of the existence of the world he creates.

There are writers who can make us laugh about the sadness, hopelessness, and isolation that we can experience. It is a gift to be able to enjoy the heartfelt agonies of Jhonen Vasquez' Filler Bunny, or the hilariously tortured existence of Roman Dirge’s bittersweet Lenore, and there are a slew of other comic book authors who have produced work documenting their own personal experiences in wrangling depression. My favorite of these is Allie Brosh's two part story: Adventures in Depression and Depression Part Two, (I just reread it to make sure I got the links right and got really choked up. It’s a doozy and I’d recommend the physical book if you go in for that sort of thing). All too often, one of the characteristics of depression is an inability to express what is going on in any relatable way and it is one of the reasons it can be so hard to just “ask for help” (as we’re so often advised). The level of clarity with which the author is able to communicate the broken logic which is happening inside the depressed brain is astounding.

While other authors have found ways to express and expose the insanity that is life, Ware’s early work never steps away from the protagonists enough to express any conscious awareness of experiencing specific emotion. Instead Ware depicts his characters experiencing their lives while blithely attempting to carry on, rarely having the perspective necessary to understand the bigger picture. He leaves the reader alone to comprehend and witness the burden and toll life takes on the characters. As in real life, his characters don’t stop to examine their emotions or what they mean, they just get on with the process of living, with only the meanest of tears once in a while to elucidate their burden.

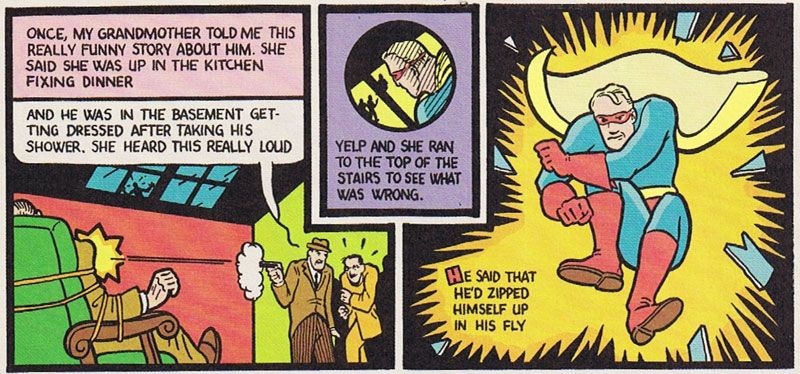

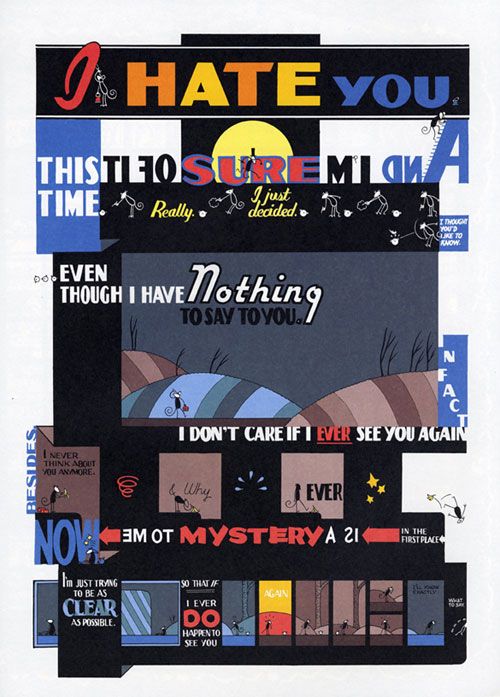

Instead of discussing emotions at a remove, Ware expresses emotions directly through the medium in a variety of ways, encouraging us to join the characters more intimately. Sometimes he creates the feelings of dissonance by moving erratically between scale and layouts with no logic or rhythm, forcing the reader to move the book around. By putting the wrong dialogue into a comic book story he evokes the way it feels when we are unable to focus on the here and now, when we can't experience events as they happen and instead becoming consumed with memories of the past and our regrets. At other times Ware expresses the feeling of inevitability, of being at the whim of fate by observing objects more closely than people.

Ware doesn’t skimp on ideas, never relying on one single moment or device and we can learn a great deal about the potential of the medium by following his work in these early, short Acme Novelty Library comic books. Unfortunately a lot of them appear to be out of print (I checked the Fantagraphics website for you), but I’m recommending them anyway in the hopes that you’ll be able to pick them up in used book stores, or borrow them from friends. Ware’s work is always packed with visual tools and while these early short stories may have a haphazard quality to them, it is there he first lay his tools out in preparation for the greater works to come and so we can learn the most from.