In "The Unwritten," Mike Carey and Peter Gross have delivered a comic book series that has blurred the lines between fact and fiction ever since it debuted in 2009. A love story to literature, "The Unwritten" follows Tom Taylor -- the son of a famed children's novelist -- on his epic adventures through reality and the novels that have defined each generation dating back to the times of Cane and Abel as he explores not only his own existence but that of the characters inhabiting the worlds around him.

After 59 issues, the series closed at the end of 2013 in a wickedly intoxicating arc featuring the characters from Bill Willingham and Mark Buckingham's "Fables," and many believed Tom's story would end there -- in Fabletown. But that wasn't enough for Carey and Gross. Simply put, the long-time collaborators don't like their creations getting of that easy. And so, this week, "The Unwritten: Apocalypse" debuted, picking up where the last series left off.

Merriam-Webster defines "apocalypse" (apoc·a·lypse) as "a great disaster or a sudden and very bad event that causes much fear, loss, or destruction." That doesn't sound good for Tom and his friends Lizzie Hexam, a character created by Charles Dickens for his last novel, "A Mutual Friend" now living in human form, and Richie Savoy, a journalist-turned-vampire.

In the first COMMENTARY TRACK of the new year, CBR News connected with Carey and Gross to better understand how far the lines have blurred for Tom and if the world he's returned to after "The Unwritten Fables" arc is recognizable to the boy wizard/z-list celebrity, who has grown to become arguably the world's most powerful being.

Which world, and how many actually exist, remains a question but Tom is on the path to finding out and readers of "The Unwritten: Apocalypse" are along for the ride.

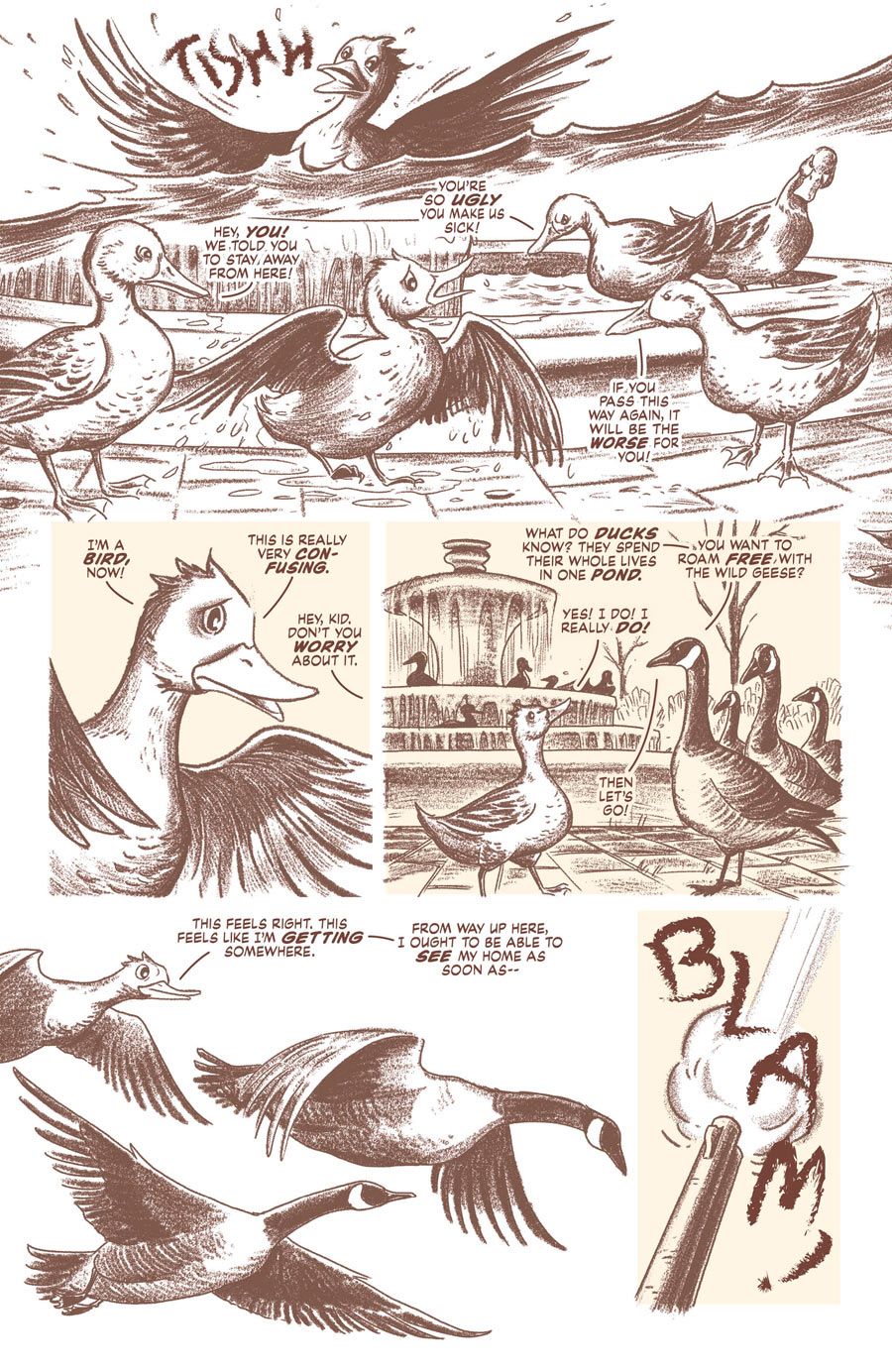

CBR News: As "The Unwritten: Apocalypse" opens, Tom Taylor is traversing through famous fables featuring sentient animals. The artwork and storytelling is beautiful and original, but it's also an homage to these legendary tales. I'm not suggesting for a second that you are entering Shia LaBeouf territory, but as our world moves faster and faster via the internet and social media, how vital is remembering and celebrating our past and the art of storytelling?

Peter Gross: I think it's very interesting that you bring up Shia because I just brought him up to Mike the other day. I was proposing that we introduce a character based on him, because he does crystallize a lot of what we talk about. We've had a lot of discussion about whether copyright is a good thing or a horrible thing. What would happen if Superman was copyright free? And people could add onto his story? Maybe we would end up with incredibly powerful stories that add a whole dimension of life to our existence because they would be able to build in a way that they can't build otherwise. I don't know. On the other hand, I want to get paid for what I do. [Laughs]

Mike Carey: In the wide and historical context, copyright is an aberration because for most of human history, there were no walls. Stories just borrowed freely from each other and great stories would be told and retold and appropriated and misappropriated endlessly. It almost feels like the walls were put up to stop the free flow of a certain kind of creative energy.

Gross: In the context of "The Unwritten," I think copyright is a tool of the Cabal. But you could argue the complete other side of it.

Carey: We wouldn't be able to make a living without it.

Gross: I think we should write to Shia and his people for permission to use him and his likeness in our story. If they said "No," it would bring up a lot of interesting issues. Wouldn't it? [Laughs]

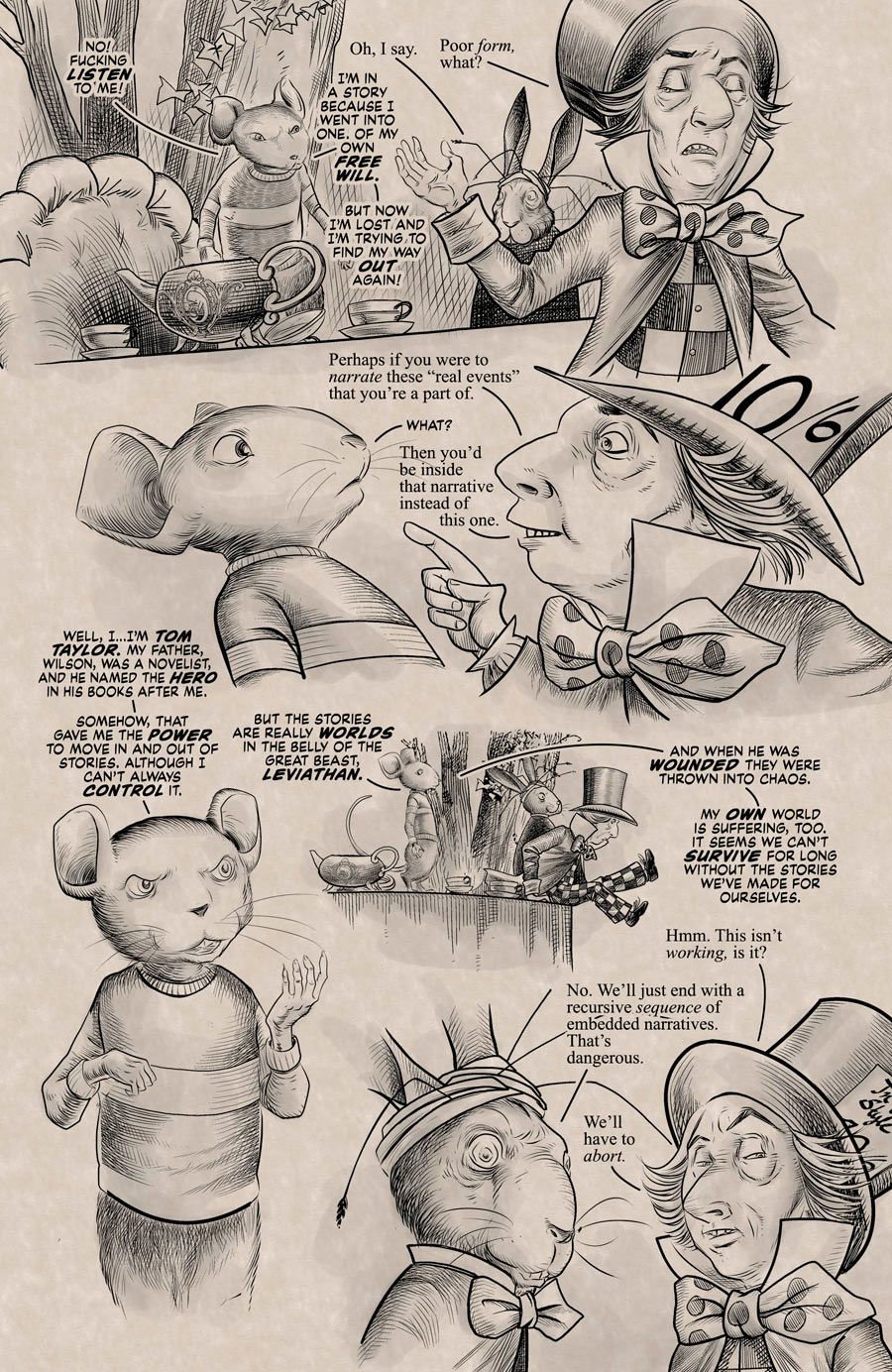

This is nothing new for "The Unwritten," as you've said it's built upon great stories from our past but in "The Unwritten: Apocalypse" #1, the characters look and feel and sound like their original iterations, which is different from how you usually blend them into world of "The Unwritten." Has Tom's movement between these stories transitioned to a higher level of understanding, or has the story moved in a different direction?

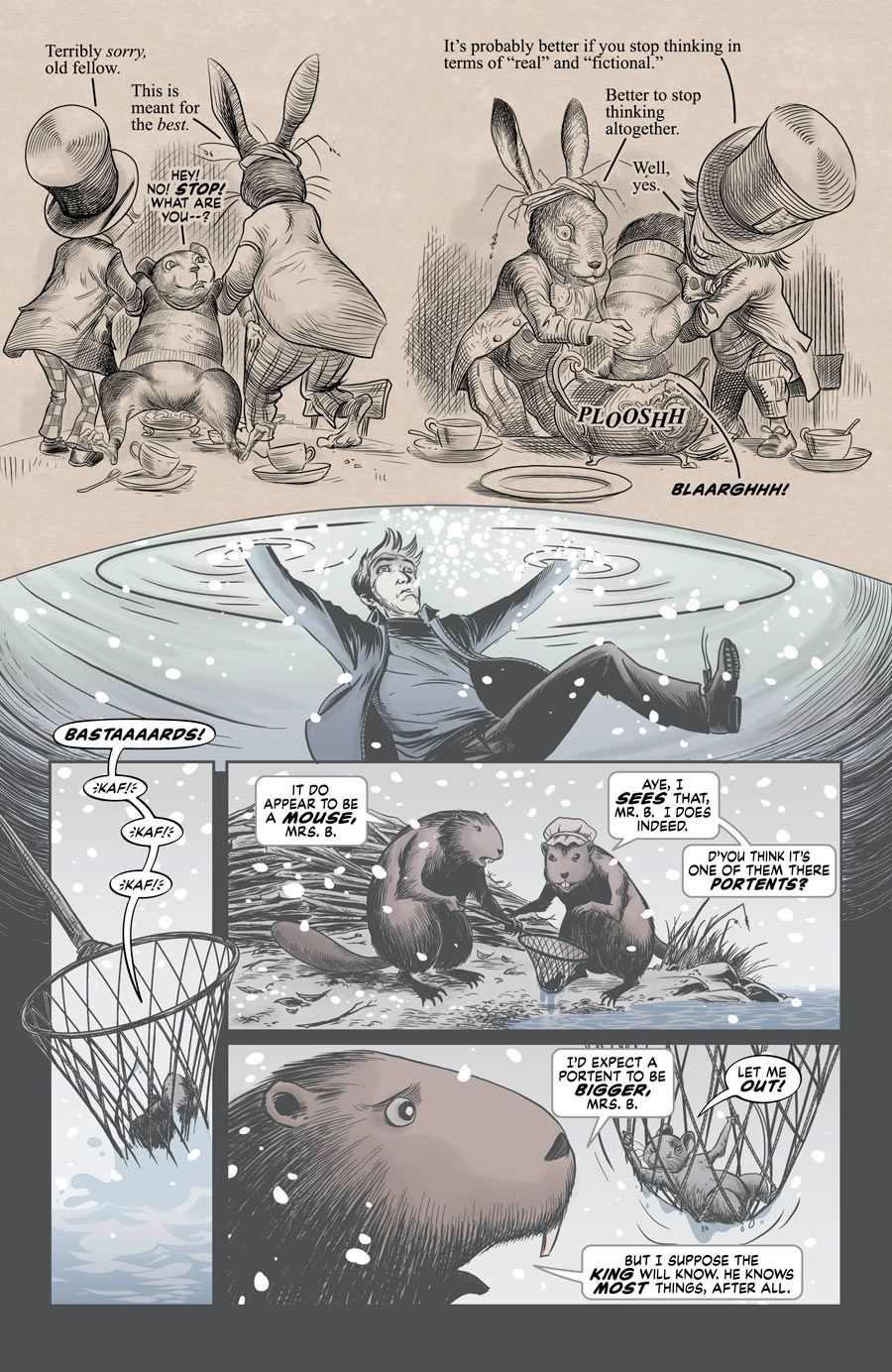

Carey: What we're doing is that we've picked up on what Tom has learned from the "Unwritten Fables" arc. There is a crucial scene at the end of the arc where he is talking to Frau Totenkinder, and she basically challenges his superficial distinction reality and fiction and says, "It's not really like that." The stairwell of the world has no top and no bottom. You can't imagine that your world is somehow more privileged over all of these other worlds. As we go into "Apocalypse," Tom is trying to make his way back home to his reality, his baseline, but he's perfectly well aware that there is no up or down here. There is no particular direction that leads home, because reality is not a separate and distinct thing.

Gross: And there is a very existential element to this opening, too. Tom unmade everything for himself at the end of the "Unwritten Fables" arc, and now he has start from that point. In other sense, if Tom's not in the forest, is there a forest? Is there a reality if Tom's not there?

Carey: Exactly. How far is the road that he's walking along?

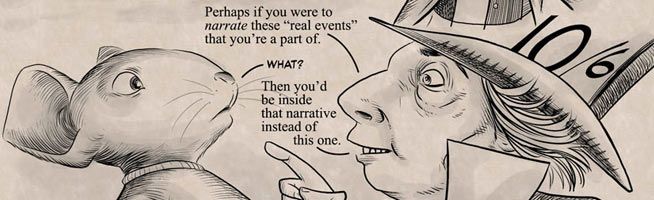

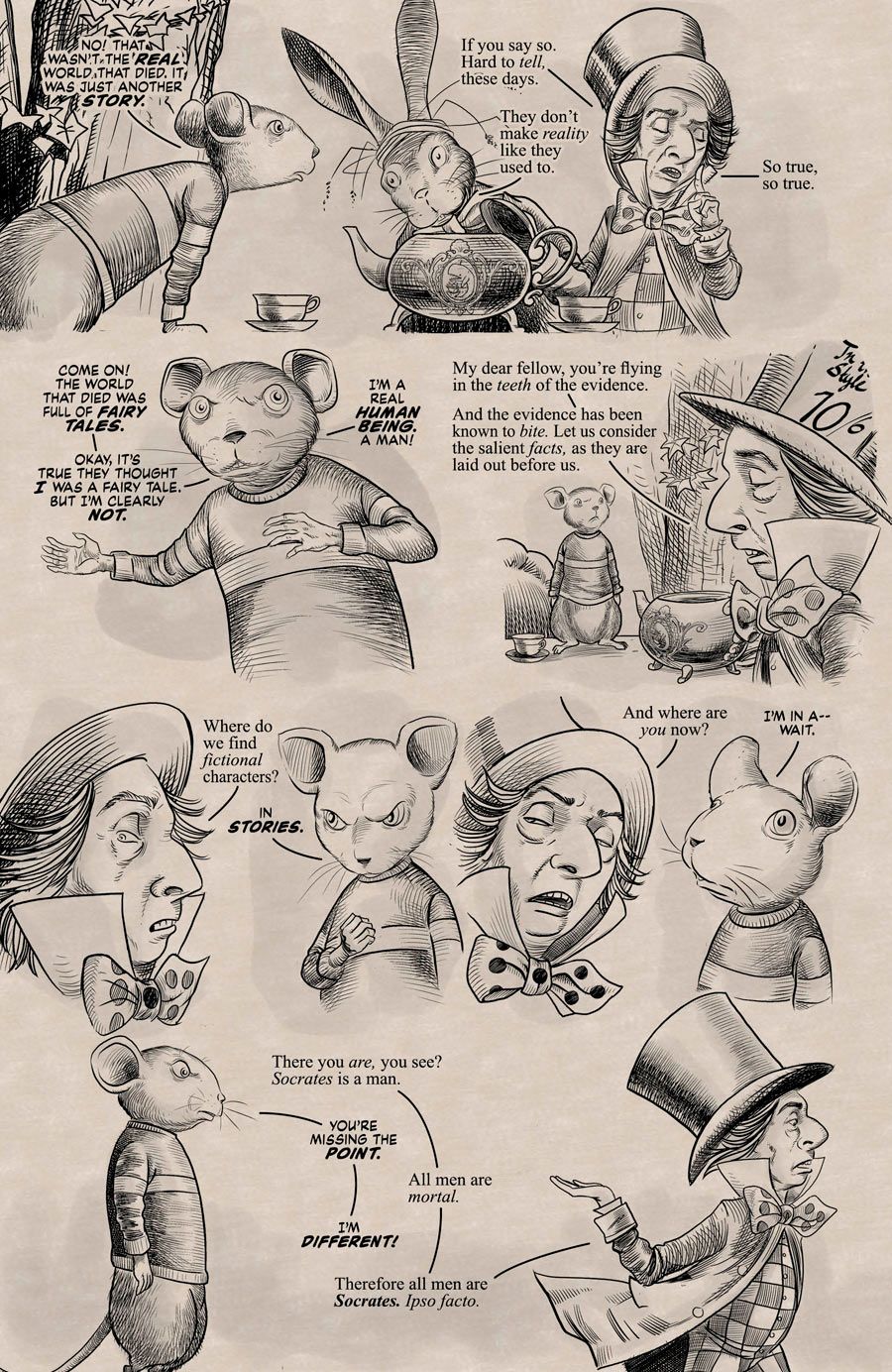

Who better to serve as a voice of reason than the March Hare? But he has a high moment of revelation when he states, "They don't make reality like they used to." Do you agree? As we live our lives in the Information Age and people hide behind avatars and usernames online, have the lines been blurred and the way we perceive reality changed?

Carey: I think reality has always been a story that we tell ourselves within an arena of different stories that makes sense to you and makes sense of you. Kurt Vonnegut in "Cat's Cradle" has the idea of foma, which are the lies that make you wise and beautiful and strong. I don't think there is anything special about our age except, as we've discussed before, the ways in which stories are propagated. And the speed and frictionless ease of which stories are propagated. That's the difference.

Gross: I think there is an urge in humankind to create surreality. In our stories, we are always trying to create another reality; in our art, we are trying to create another reality. Look what you can do with movies and 3D printing. We're trying to create another reality alongside the other reality that we have. It's our basic nature. It's like striving to become God. There's something going as we are able to create virtual realities.

Carey: It's a turning point in human evolution. The moment when we learn to make counterfactual worlds, what would happen if I poked that beehive with a stick?

What would happen if I piled rocks up in the streams? The water level would rise up and create something different. It's that ability to leap outside of what's really there to what might be there that allows us to manipulate the world -- to turn the world into our tool. It's both our greatest strength and our greatest weakness. We're storytellers before we're anything else.

Gross: If I gave any credence to the idea of there being a God, it would be that we are the gaming creations of some other reality. [Laughs] We're like "Sim City" becoming self aware. And we're going to end up creating our own reality, which we will be the god and then they will become aware and then they will create theirs. Maybe we're just this series of toys...

Carey: Links in a chain.

During the same sequence, Tom is playing the role of the Dormouse but he is self aware and says, "I'm TOM TAYLOR, my father, Wilson, was a novelist, and he named the HERO in his books after me. Somehow that gave me the POWER to move in and out of stories. Although I can't always CONTROL it." Is that what's next for Tom in "Apocalypse?" Learning how to control his power. Because as Voltaire, and more recently Uncle Ben taught us, with great power comes great responsibility.

Carey: It's only one strand among many. We talked about him coming to terms with his own nature, which of course means that there is no definitive answer to the question, "Am I Tom or am I Tommy," because he's both, by virtue of his heritage. "A man was your father and a woman was your mother but a word was your midwife." That's what Madame Rausch told him once. He has a unique place in what's about to happen, but he needs to figure it out. He needs to make a plan and then he needs to enact it. He needs to carry it out. And he is still in a position where he can do that.

Gross: In this first issue, he is remaking himself. It's key to how he's going to approach his ability and understanding of himself.

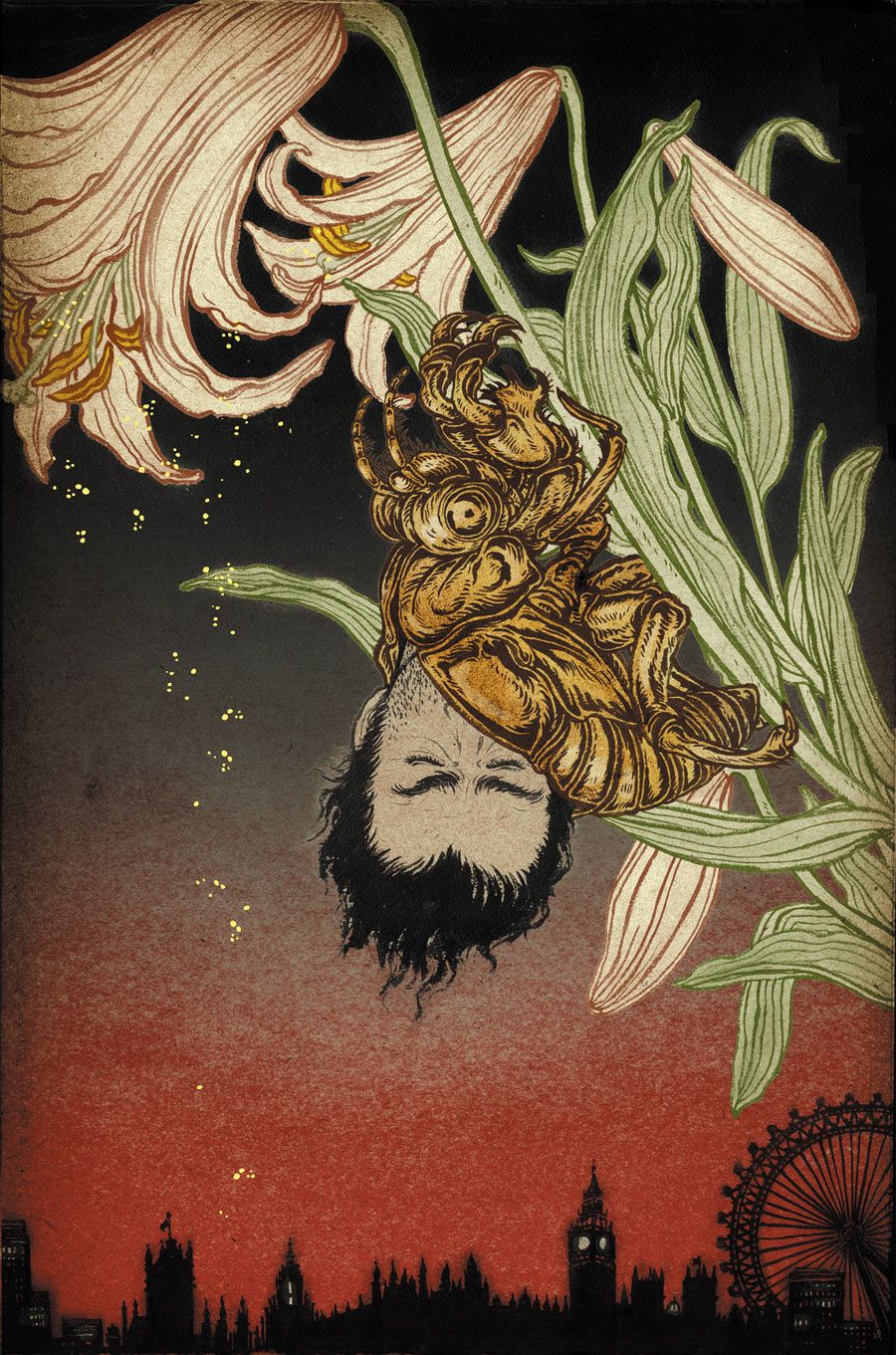

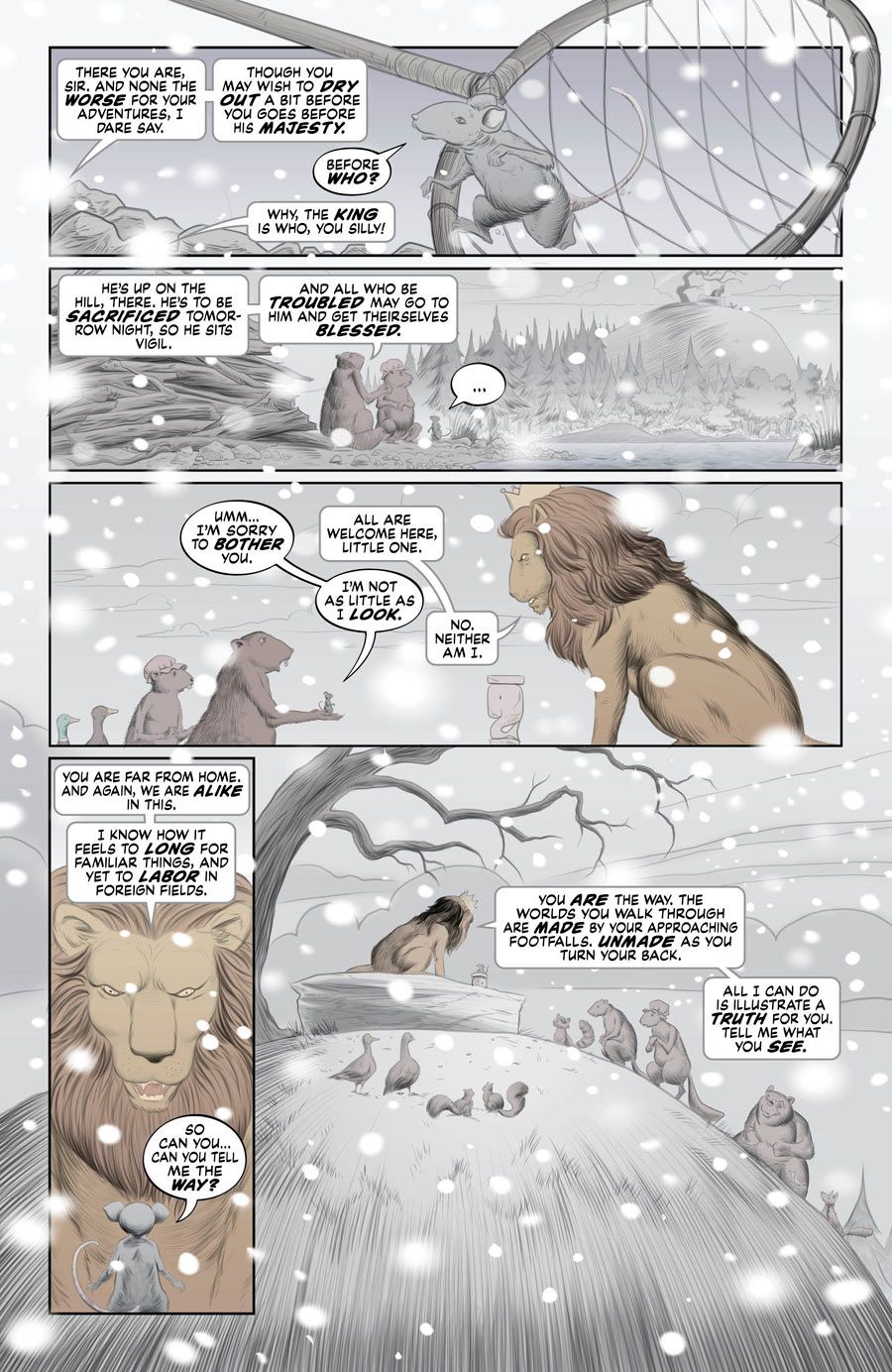

The sequence with Aslan from "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" is beautiful and, again, has powerful language from Aslan. "You ARE the way. The worlds you walk through are MADE by your approaching footfalls. UNMADE as you turn your back." This is quite literal for Tom, but it's true for all of us, isn't it? In the morning, we all make our own beds.

Carey: Yes, you're right. It is true for all of us. It's kind of true in a different way for Tom, but it is key to everything that we're saying. It was Peter that insisted that point me made in one of our marathon phone conversations. Without Tom being there, these worlds would take a different form. And they would articulate in a different way. It's like Schrödinger's cat. The observer is part of the system. Until you open the box, the cat is both alive and dead -- everything is everything. You make it what it is by the way that you interact with it.

When you consider the power and gravitas of Aslan from "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" or what you have built with Tom Taylor over the past five years, can you consider a fictional character a living thing?

Gross: Good question. It goes back to copyright and the building of these stories. I think fictional characters often taken on a life of their own beyond what the intention was.

Carey: At the point when the story reaches the mind of the reader or the viewer, I think something happens that is beyond the conscience control of the creator. The meaning that arises is not something that can be predetermined. That's when stories come alive. It's their indeterminacy. The fact that the story means something different for everyone that encounters it and impacts them differently based on their previous experiences and on the way that they see and make the world around them.

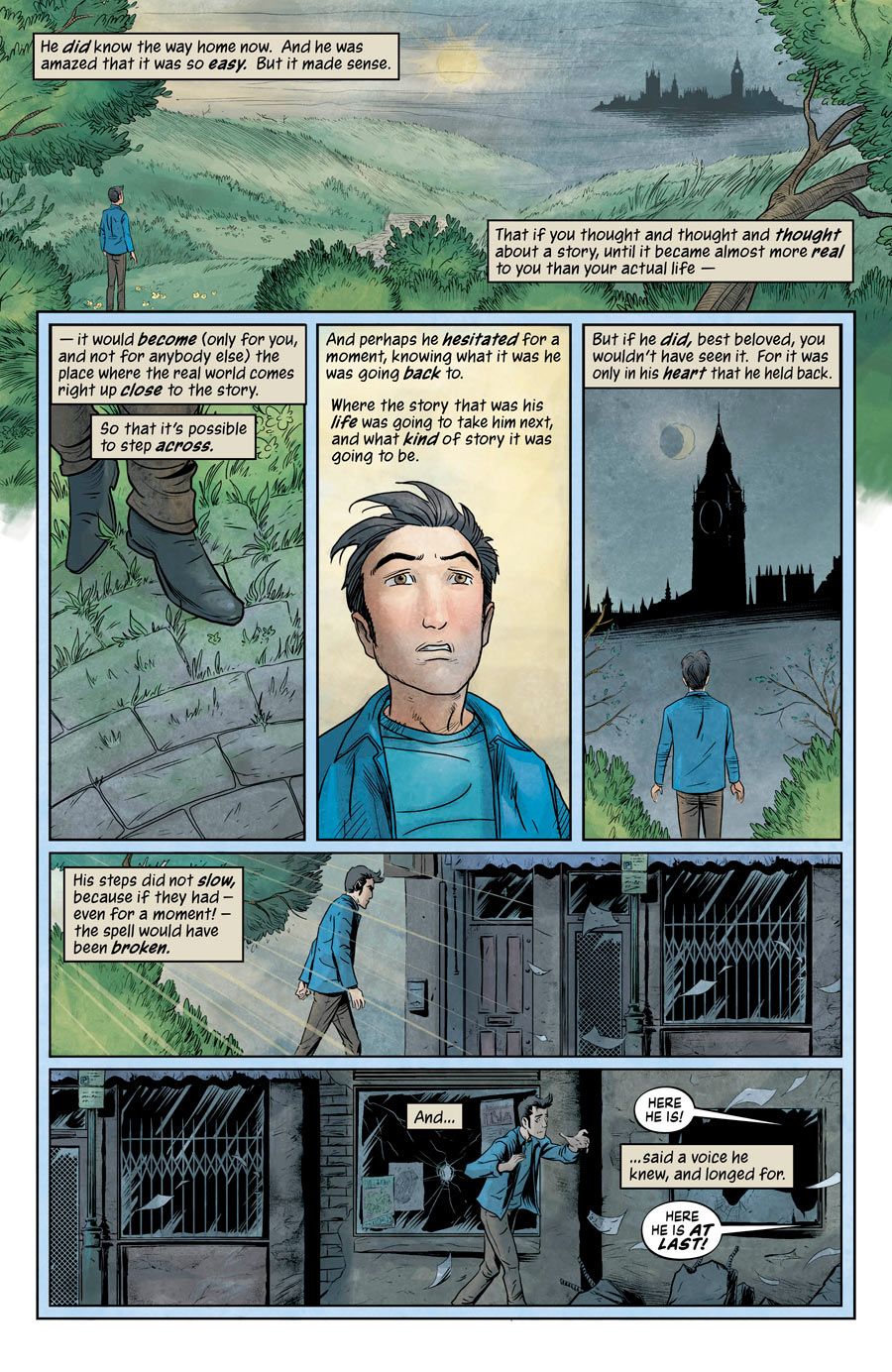

Midway through this issue, Tom returns to Willowbank Wood as his human self and instead of feeling relief for a character I have followed for 60 issues, everything from his language to the look on his saddened face makes me anxious for what lies ahead. As his creators, and going back to my last question that Tom has become a living thing, does it hurt to put him through these trials -- these herculean labors?

Carey: We've always had a particular confection of Tom and what Tom's arc is, and we've stayed true to that. Often, as we've discussed before, things happen in the story because we become fascinated by this or that and going in one direction or another. But Tom and Tom's arc are very much at the heart of what we want to do in this story so he's always been heading towards a particular endpoint for us. I guess that what makes it easier because we always knew that these things were in store for him. He was always going to have these things to face and accept. I think that he is a rock-bottom kind of tragic figure.

When we first meet him, when he is trying to prove that he is a real boy and not a puppet, he's looking for something that isn't there. And it isn't there, because it's impossible that it would be. He can't have the complete independence and autonomy that he wants, so there is something about his arc that has a very tragic flavor to it.

Gross: Your questions will be more apt at the end of all of this. Ask us that same question a year from now and we'll be able to give you a much more complete answer.

On the final page, Tom is reunited with his friends Lizzie Hexam and Savoy, but he's returned to a world that has been utterly destroyed. Savoy says, "If you'd gotten here SOONER, maybe we could have save the WORLD."

Gross: Yeah, he's back, but you can tell by the visuals that the world is a very different place than the one he left.

Carey: And Richie's line is key. There's a sense that an awful lot of things have happened that can't be undone. Now, Tom has to find a way to move forward from this terrible situation.

Gross: I shouldn't bring this up, and it's not a spoiler or anything, but whenever I see that last page, I think, how do we even know that this is reality? That's not even a question that Tom is going to be asking, but with everything that we've done and all of the stories that we've told, how do we know if there is a difference anymore.

Carey: There's a sense that it's the real world because he's come back to it and that's where he is.

Gross: But is it fiction? Or is it real? It will blow your mind.