I included the name of the story to indicate that this is NOT the Denny O'Neil/Denys Cowans series from the 1980s, but the mini-series that came out in 2005. Now you know!

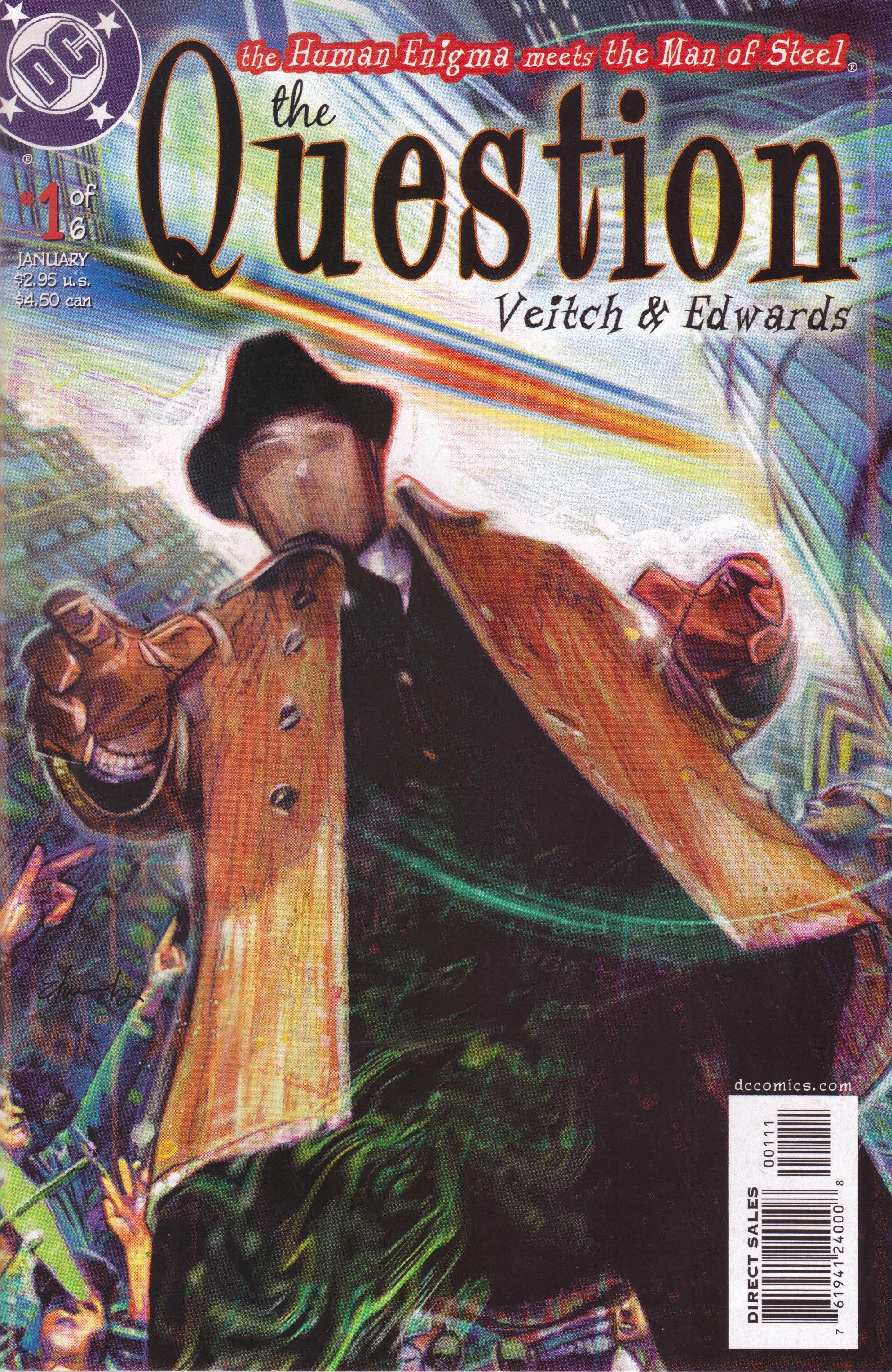

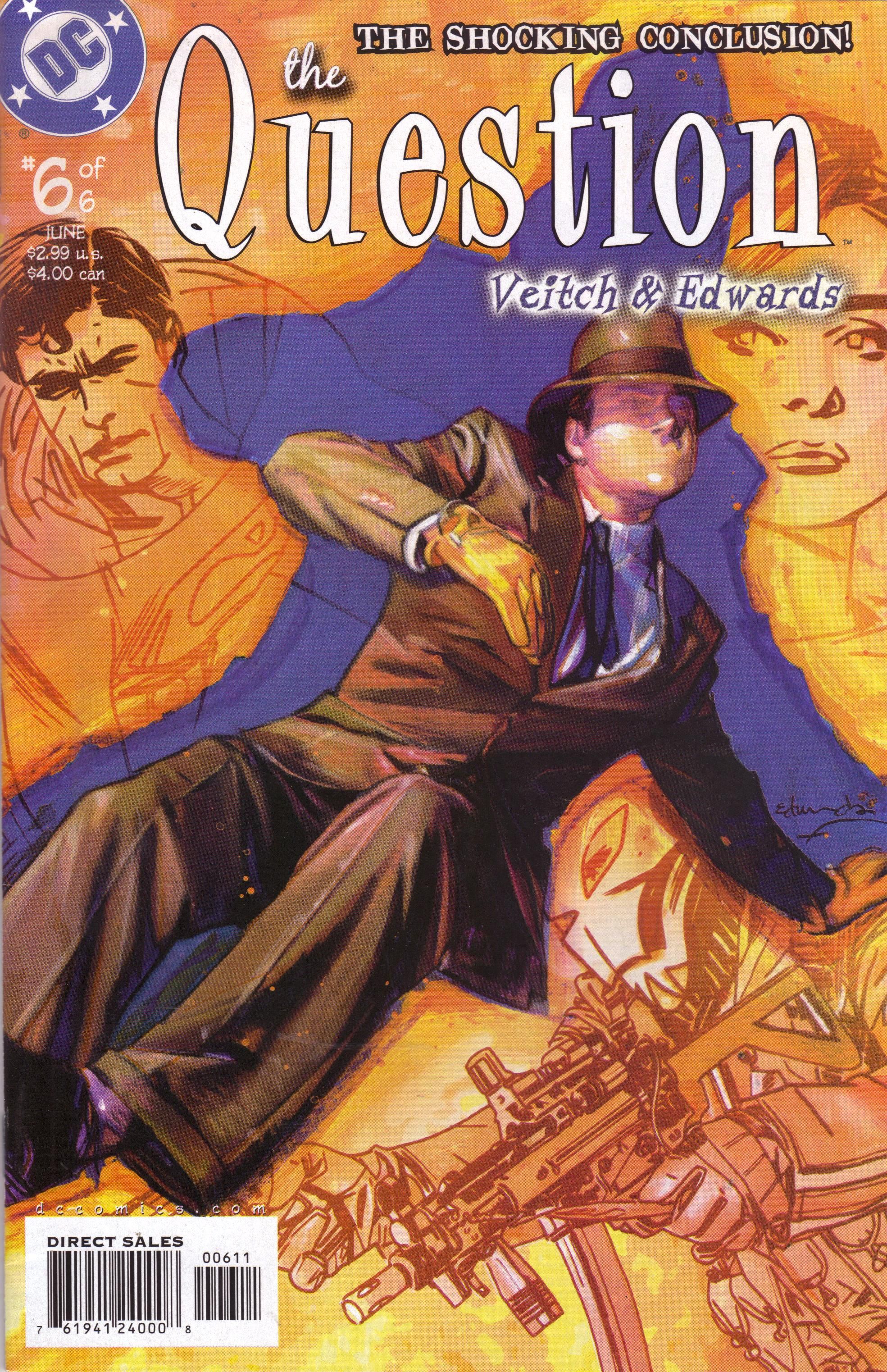

The Question by Rick Veitch (writer), Tommy Lee Edwards (artist/colorist), and John Workman (letterer), with 3-D models built by Don Cameron.

Published by DC, 6 issues (#1-6), cover dated January - June 2005.

Sure, SPOILERS. C'est la vie!

There exist certain comics that are puzzling. One cannot believe the publisher actually published it, for instance, because it's so oddball that it seems to stand outside their purview. Or the comic itself is such a strange or marvelous thing that one cannot believe someone came up with it and others didn't follow their lead.

Such a comic is Rick Veitch's and Tommy Lee Edwards's The Question, which DC published in 2005. It's a revelatory comic, even with its flaws - Veitch's main plot is interesting but still a fairly straight-forward superhero story. It's mainly due to Edwards' stunning artwork, which should have catapulted him into the comics stratosphere but which, strangely, didn't. Since this comic came out, he's done very little, but each title he's worked on is a visual treat, even though none have been as amazing as this book (he's done a lot of movie work, which obviously accounts for a good deal of his time). This remains a strange curio in the vast landscape of comics, but occasionally, those neglected titles give the most joy at seeing what comics can do.

Consider The Question. Neither Veitch nor Edwards were (or are) big names who sell a lot of books, even though Veitch will always have some cool cachet and Edwards has always been a good artist. The Question is not a big name, despite his pedigree, association with Steve Ditko's more extreme politics, and the well-regarded O'Neil/Cowan run. So why does this series even exist? It seems to be set years earlier than its publication, because Superman's death and resurrection is a lingering plot point. It doesn't have much in common with the direction of DC in the middle of the decade, and in fact Vic Sage was quickly divested of his Question identity not too long after this series was published. It's a big step forward, art-wise, for Edwards, so I very much doubt that it was done years earlier and shelved, but it is a curious little comic. Plus, it's never been collected in a trade paperback, which in this day and age is a bit strange.

The basic plot of "Devil's in the Details" is fine, even a bit more interesting than your standard superhero plot.

In the first issue, our hero is tracking some bad guys in Chicago and he meets a hit man called the Psychopomp, who apparently has the ability to kill someone so well they stay dead. In a superhero-filled world, this is a handy ability to have. The Psychopomp mentions to the Question that he's been offered employment by a group of criminals called the Subterraneans, who operate in Metropolis. So Vic Sage, intrepid reporter, heads off to Superman's city, ostensibly to cover the latest scheme by Lex Luthor - a "science spire." Luthor is up to no good, naturally, and both of these plot threads converge over the course of the series. Naturally, because everyone in the DCU knows each other, Sage went to journalism school with a certain Ms. Lois Lane, but he ditches meeting her and she spends the entire mini-series trying to figure out what Luthor is up to and where Vic Sage went. The Subterraneans move around the city in a subway, finding out when Superman is occupied (or causing him to be occupied) so that they can break into places and steal things. Their leader, Minos, makes a deal with the Psychopomp to kill Superman so good that he won't never come back to life. But these nefarious dudes didn't count on Vic Sage! Meanwhile, Luthor is being Luthor, and his building is far more than it seems. He has hired an avant-garde architect and a feng shui designer to make sure that the science spire is in harmony with the planet, and it turns out it's situated at a junction point of hundreds of chi lines, meaning power will be flowing through it. If you think Luthor plans to use this power to kill Superman, congratulations - you have encountered Luthor before! All he ever does is plot to kill Superman! He's also working with the Subterraneans, of course, because they're all bad guys.

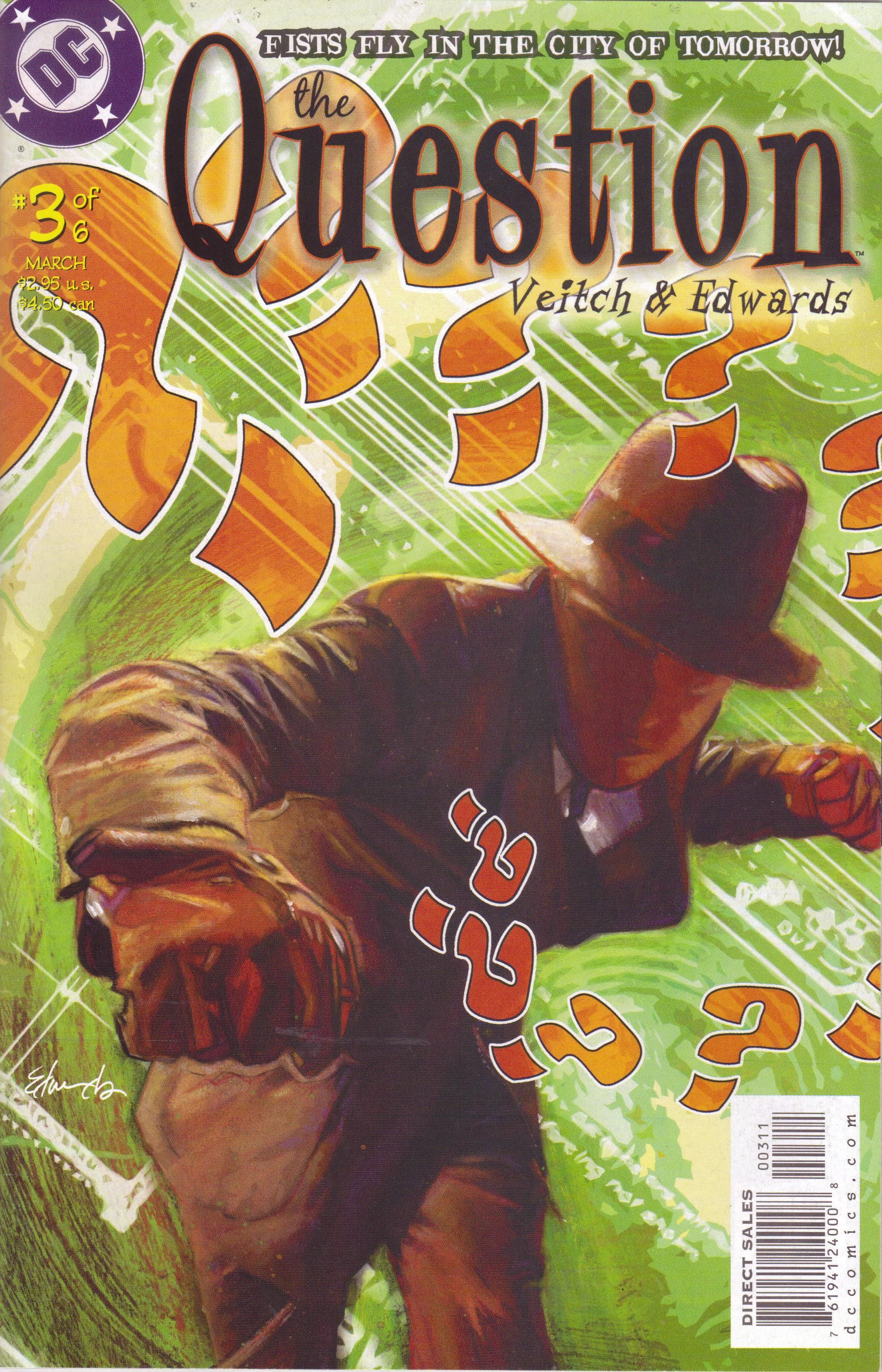

The reason the plot is interesting is because Veitch does wonder how bad guys might operate in a city where Superman lives, and he comes up with an ingenious solution. Minos and his crew track Superman's movements very carefully, and Veitch overdoes the fact that they collect payments through a tube system built into toilets, even though it's a good point that Superman would never eavesdrop on anyone in the bathroom.

They strike quickly and, if anyone - like the Question - gets in the way, the entire gang is rigged with some kind of comic-book bomb that burns them up to ash in no time at all, leaving very little trace. Of course, once Superman actually knows about them, it's easy for him to figure out what's going on, but it's still a clever plan. The science spire scheme is fine, too, because weird mystical shit works fine in comic books, and it's a plan that could, conceivably, work. It's a bit annoying that the female Asian woman turns out to be not so bad even though she's working for Luthor while the male white Northern European (he's Dutch, for crying out loud - how much whiter can you get?) turns out to be actually evil, but oh well. The plot isn't too complicated, but it has some nice twists and turns along the way.

(I should point out that I like the idea of the Subterraneans so much that when I wrote my post about 52 DC titles I would put together for the reboot, one of them was a series based on a criminal organization that operated in exactly this way. I wish that series existed.)

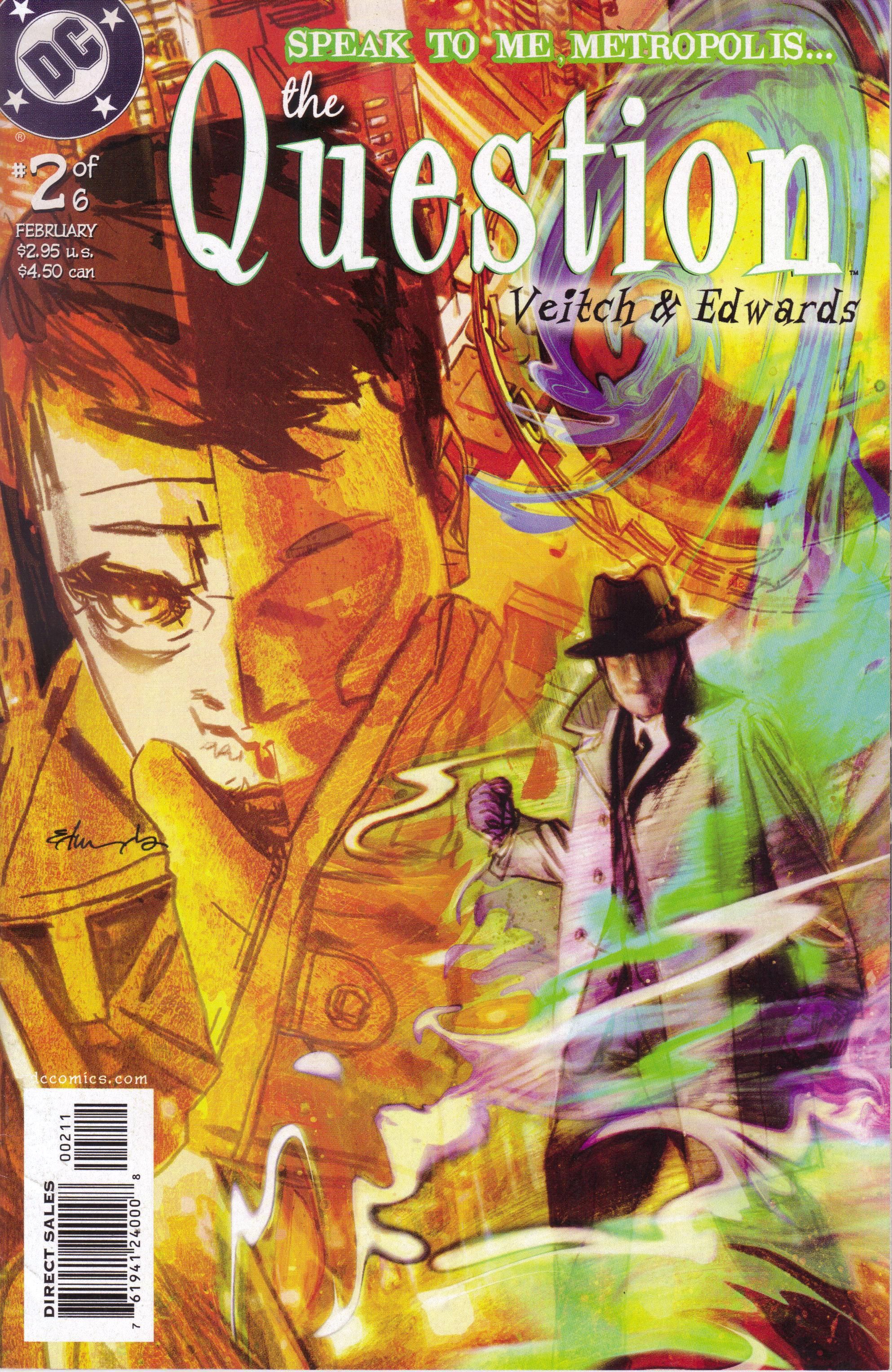

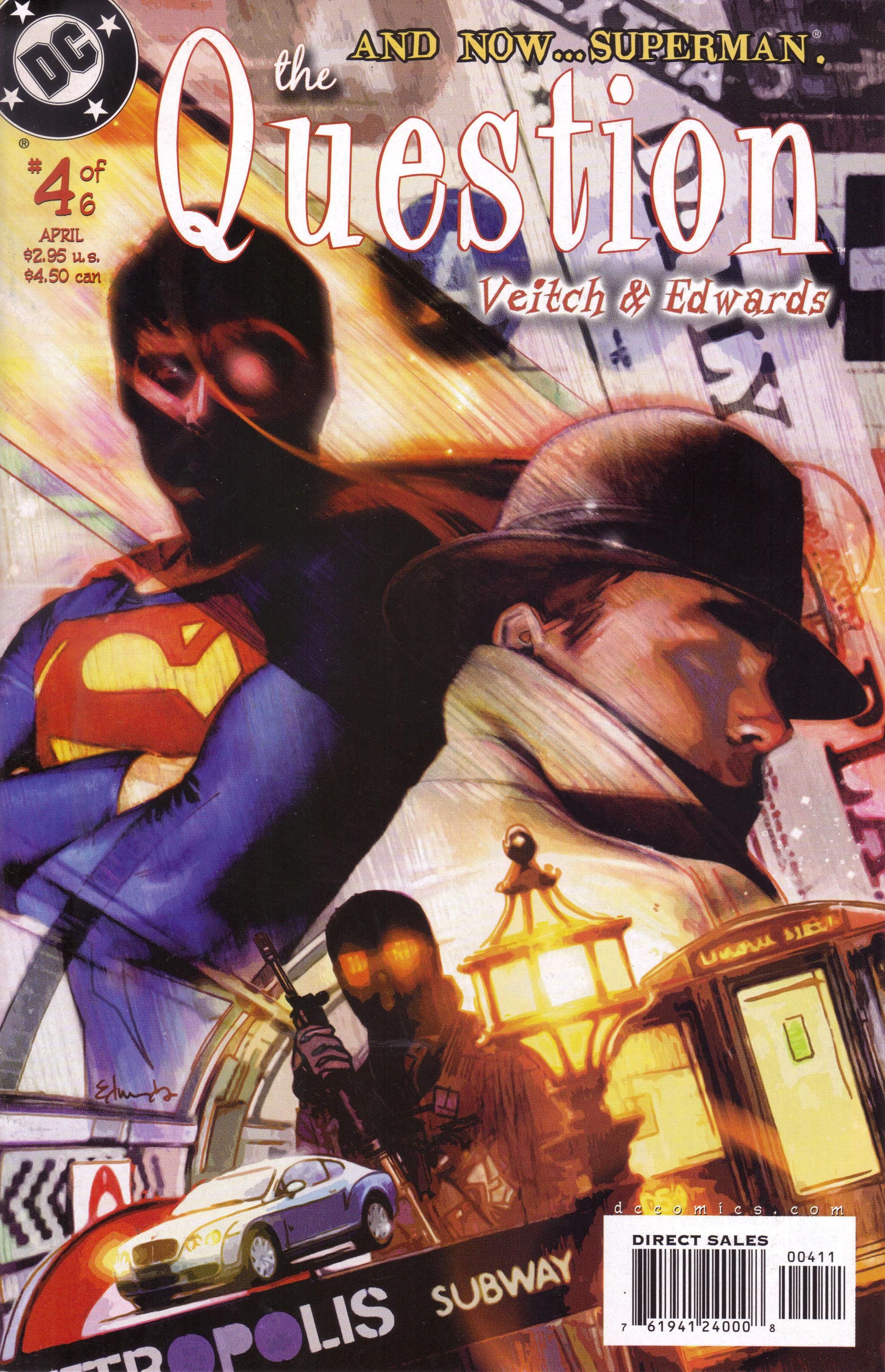

The way Veitch and Edwards tell the story, though, is what makes it so interesting. In the first issue, they start in "yesterday" and alternate with "today," showing the Question tracking the bad guys in a Chicago meat packing plant and switching from that to his train ride to Metropolis (really? the train?). It's not an original way to tell the story, and the fact that Veitch does the clever "saying something that means one thing but also alludes to something else" throughout the issue makes it even less original, but it still works. In the second issue, Veitch structures the tale differently, as Sage moves through the city's underbelly on the lower third of the pages while Lex Luthor holds court at the top of his giant skyscraper in the upper two-thirds of each page. It's a nice way to show how the Question gets his information while also contrasting Luthor's stated intentions with the fact that he's working with the Subterraneans. Sage is able to understand the city better than its inhabitants, so when a giant beam comes from the sky and Superman has to stop it from destroying Metropolis, Sage is able to discover that the Subterraneans are using that as a diversion to rob a bank, and he stops them. In issue #3, he "reads" the city to discover how the Subterraneans are getting their money. In this issue, Miles van Vliet, the architect, shows Lois all the "chi" running through the city (which Luthor plans to focus), and it looks remarkably like how the Question views the world (I'll get to that soon enough). In the fourth issue, Metropolis itself leads him to the Subterraneans and to Six True Words, the woman from Bhutan who is trying to cleanse the site of the science spire of its unquiet ghosts after the mass grave of 19th-century slaves is found there.

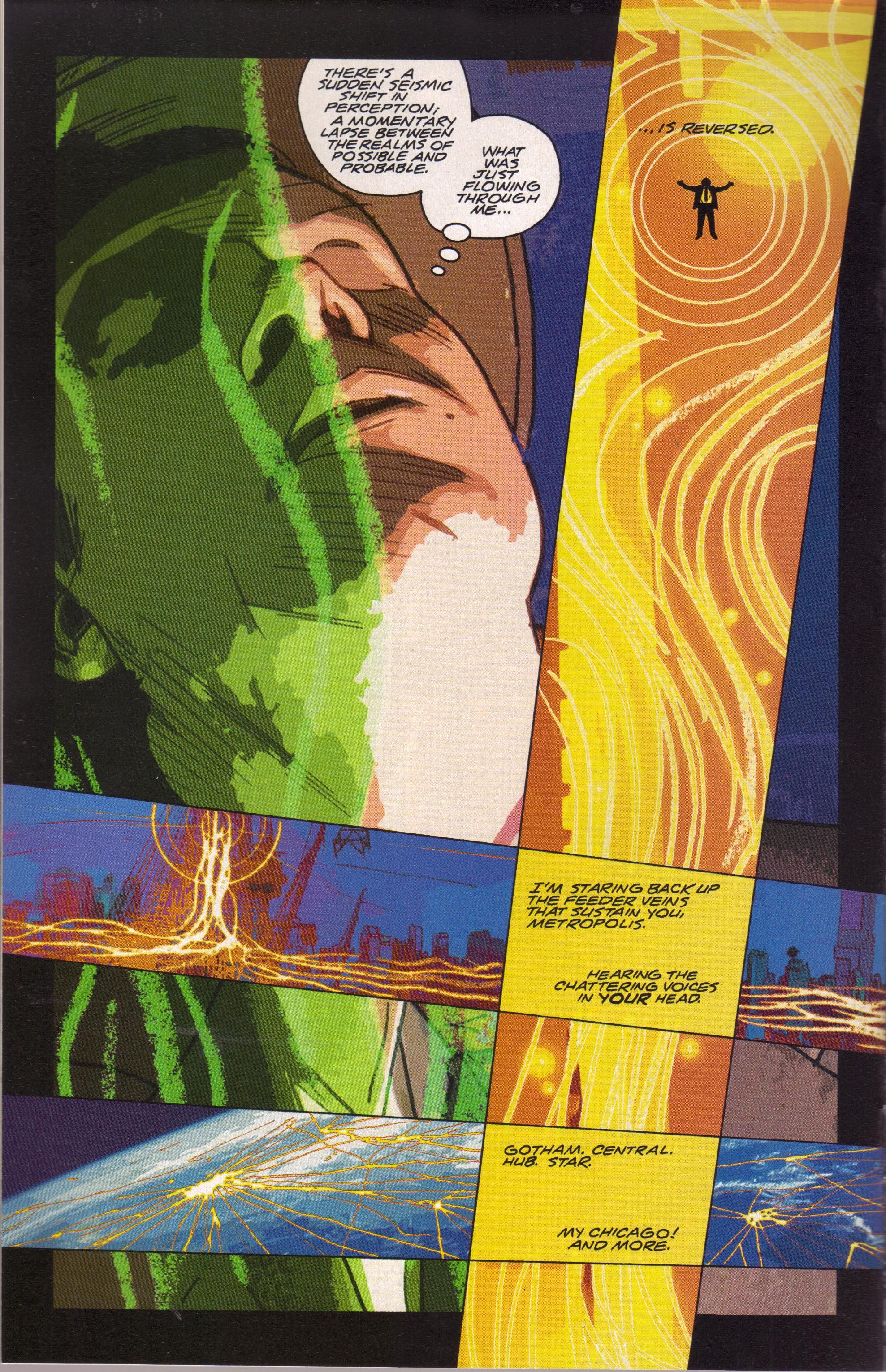

In issue #5, he communes with her spirit after she is killed and also taps into the energy flowing throughout all the cities of the world. Finally, in the final issue, he's able to use that energy to defeat all the Subterraneans, moving in and out of this reality so that he appears invisible to them when he needs to be. All of this makes the book a far more interesting exercise in superheroing (Veitch writes a very good Superman, too) than we usually get. Veitch takes elements from the O'Neil/Cowan run, and although I've never read Ditko's version of the character, he seems to take some of those elements as well. However, he blends those nicely to turn Vic Sage into some kind of "urban shaman" - he "walks between the worlds" so he can move undetected through cities and read them like few others can. There's certainly an element of Jack Hawksmoor in this updated version of Vic Sage, but the Question is more mystical and less science fiction than Hawksmoor. I don't know how "Objectivist" Steve Ditko's Question was, but on the first page of this comic, Veitch and Edwards put a reference to Nietzsche's Übermensch, which has to be some kind of nod to that vein of philosophy (although I have no idea what Rand thought of Nietzsche). Veitch's Vic Sage is fairly brutal, but it's more that he'll kill if he has to, not necessarily because he wants to. His murders, for the most part, serve a purpose, especially the shocking way he deals with the Subterraneans in the finale.

Veitch re-imagines Vic Sage a bit, even though Sage doesn't have much to do in this series. He seems to be more socially awkward than in the O'Neil/Cowan series, and his infatuation with Lois Lane is slightly pathetic, even. He's younger than she is, and he desperately wanted her to read his poetry, some of which Jimmy reads when he finds it on-line. It's as ridiculous as you might expect. Sage/The Question narrates the book in utterly pompous phrases, too - here's a sample from issue #1:

Speak to me, Chicago. Oh, paint chip peeling over bare schizophrenic light bulb. Guide me, Windy City. Oh, doomed crack baby suckling cola poison death nipple. Steer me. Oh, ancient Sisyphus elevator wheezing in monotone brownstone despaiar! Direct me. Oh, rattling elevated cattle cars hauling mad cannibal swarms of Moloch!

It's purposely silly, but it's how Sage thinks when he's engaged in his important work. Veitch can't be all that serious, and he might even be taking the piss with Alan Moore, given that Rorschach is based on the Question and, of course, there's the reference to Moloch in there. Beats me. It's actually quite fun to read this dialogue, because it's served up totally straight, but when we get to read Sage's poetry (which implies that he's already thinking about becoming the Question), Lois and Jimmy stand in for the reader and mock it openly. Sage never actually interacts with anyone except strangers on the train, implying that he keeps his distance from everyone who might be a friend. Veitch's Vic Sage is a lonely person, but he's never distracted from his mission. Veitch doesn't delve too much into this loneliness, but it's interesting that he can convey it nicely without being too obvious about it.

It's Edwards's art that stands out, of course, and makes this comic far better than many others. While Veitch's story is clever, it's still just a superhero story with a slightly mystical bent. Edwards, as far as I recall, debuts his latest style in this book, as he mixes pencil work with Photoshopped backgrounds and computer-generated images. For the most part, his inks (if this is in fact inked) are light, and he colors the book himself, which is always a plus. I've been looking for something about his process, but I can't find anything specific, and I'm not smart enough to know how he created this artwork. I imagine he used a Wacom, as he's used it before, and that allows him to digitally ink and color the entire thing while adding the backgrounds. What we get is a stunning blend of solid figure work, beautifully integrated computer effects, backgrounds that are obviously not drawn but look as if they were, and coloring that blends the two elements of the panel together very well, presumably through standard "washing."

The lack of holding lines in the backgrounds softens the entire comic but also makes the figures stand out more, and then the coloring helps tie them all back together. What this all means is that the entire package is dazzling, as Edwards contrasts the brightness of Metropolis superbly with the darkness at its core. And unlike many artist who aren't as skilled as Edwards is, the computer effects help make the book look more "realistic" and don't distract from the inherent silliness of, say, a man dressed in red and blue underwear. I'm extremely curious about the process by which Edwards created this book, because it's truly amazing.

He also chooses a fascinating way to show how the Question views his world. We see this on page 1 of issue #1, as the Question moves through Chicago on his way to the meat-packing plant. The panels are split - about two-thirds show the Question in the "real world," but the other third shows him in silhouette against a yellow background, "speaking" to the city. This allows him to filter out all the distractions of the city and focus on what's important, plus it allows him to see the reality behind the façade. In some of the more innovative storytelling techniques in the comic, at certain points he's fighting in the "spirit" world while he's talking to someone in the "real" world. When he meets the Psychopomp for the first time, they talk about their similarities (they both walk in two worlds) while their silhouette figures battle physically. In issue #6, he's able to move in and out of this "spirit" world to remain invisible to the Subterraneans as he fights them.

One of the highlights of the series, artistically, is in issue #4, when Superman tracks down the Question and lays down the ground rules for operating in Metropolis. Edwards never shows Superman's face clearly in close-up, and when he looks directly at the reader, we see him through the Question's eyes. Superman is packed with energy, so the Question sees him as dazzling light sparking off his body, completely different from the silhouettes that the rest of the world appear to be. Superman isn't in the book all that much, but this brief exchange shows how important he is - he shines even in the Question's "spirit" world, where people move in shadow. Edwards does this when he shows the chi lines flowing into Metropolis, linking the energy of the world with the energy that powers Superman. Of course, Superman's is solar energy, but both sources are powerful, and Superman reflects that. In issue #5, Edwards goes further and links the Question to chi energy, which allows him to tap even more in this "spirit" world and defeat an entire cadre of Subterraneans. When the Subterraneans use special equipment to "see" the chi and therefore see the Question, they also see the ghost of Six True Words, who has allied herself to the Question. The choice of using this bold art and color pattern allows Edwards to circumvent the usual ways of showing mystical stuff in comics, with wispy figures and wavy lines. The book is better for it, because it really does look as if the Question is moving in two worlds.

As I wrote above, The Question has never been collected, which just feels odd to me. I get that Vic Sage was soon not only no longer the Question, but not even alive (Renee Montoya replaced him a year after this mini-series finished), and now that we've had a reboot of the entire universe, the chances are even more slim that it will get a trade. Not impossible, but slim. However, it's a comic that should be easy to find, and it's a nice obscure gem of a book. If you've enjoyed Edwards's art on some of his high-profile projects like Turf or his Marvel stuff (Bullet Points, Marvel 1985), this is a good place to see that style in service to a far more radical story, which makes it even more bizarre and beautiful. It's a fascinating book that, while seeming deeper than it actually is, does a lot of interesting things with familiar icons and how they operate within this fantastical universe. It's the tension between Superman's glorious adventures and the Question's more gritty crime-fighting that helps make this a curious masterpiece, but a gripping comic nevertheless.

I've been slow with these posts, I know - I had a lot of comics to read between this and my last post, plus my daily posts keep me busy. I can always point you toward the archives if you're needing some long-winded analysis to read!