Comics Should Be Good! - the only blog with two posts about this particular comic! That's just how we roll!

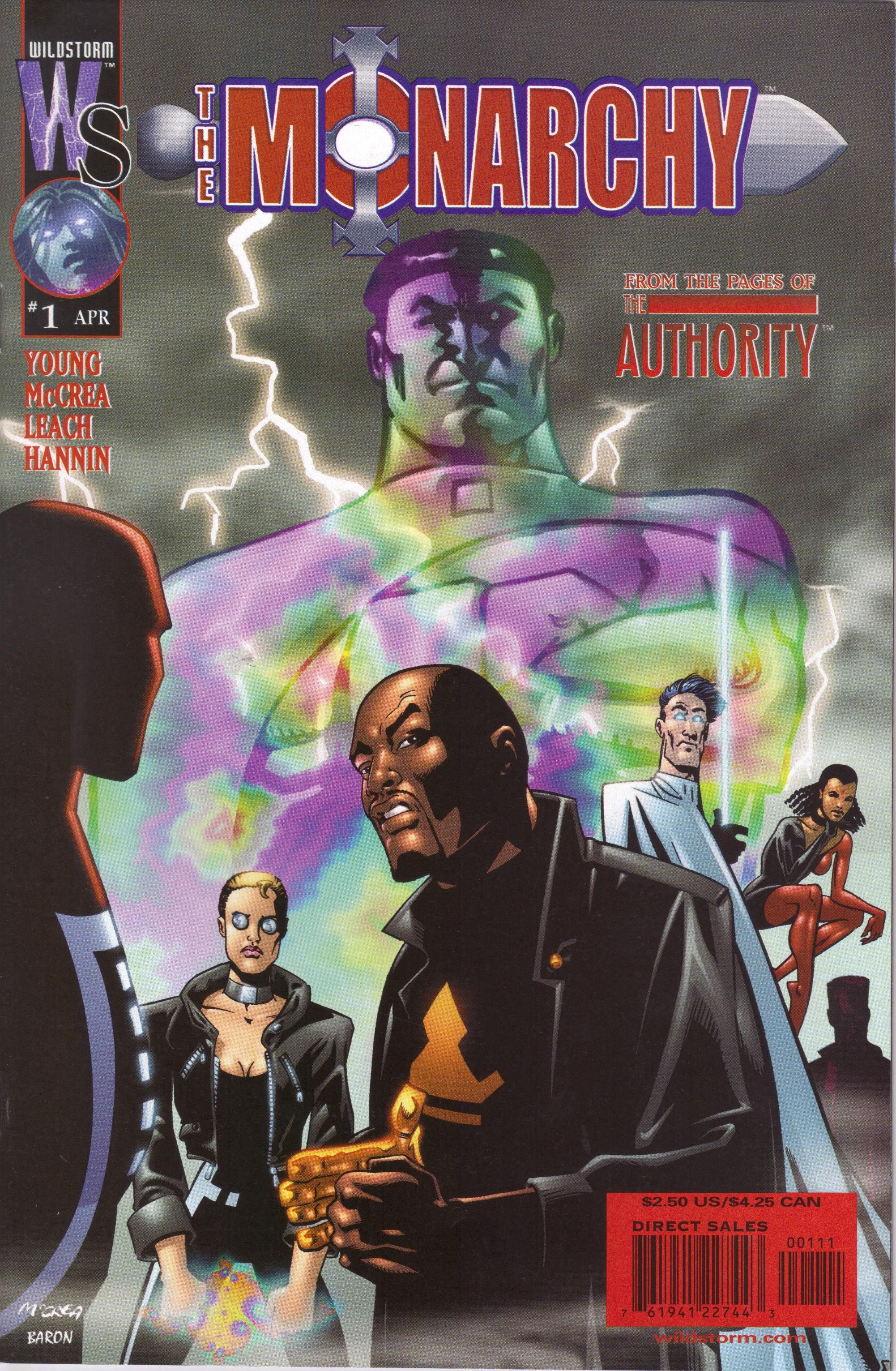

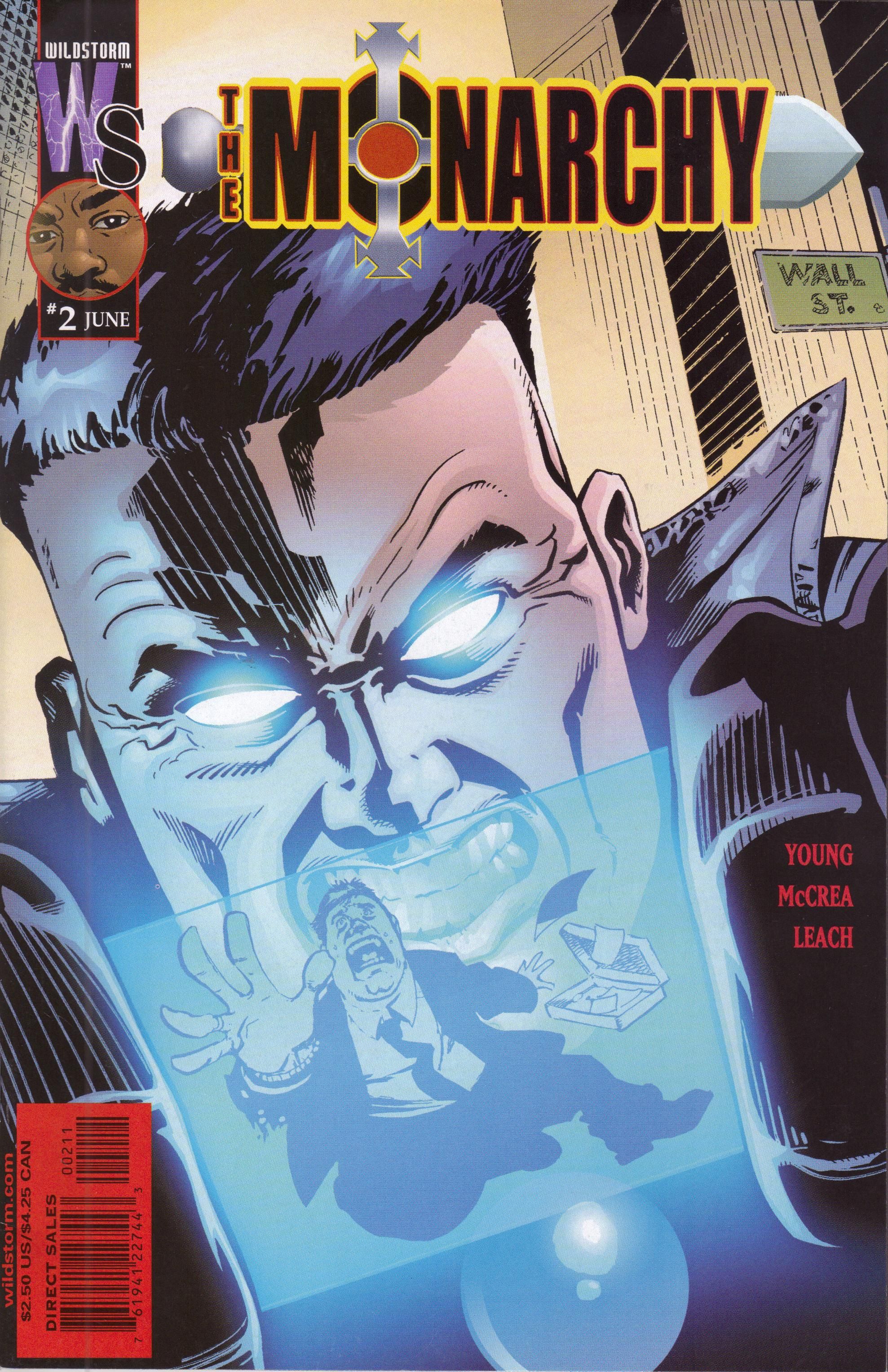

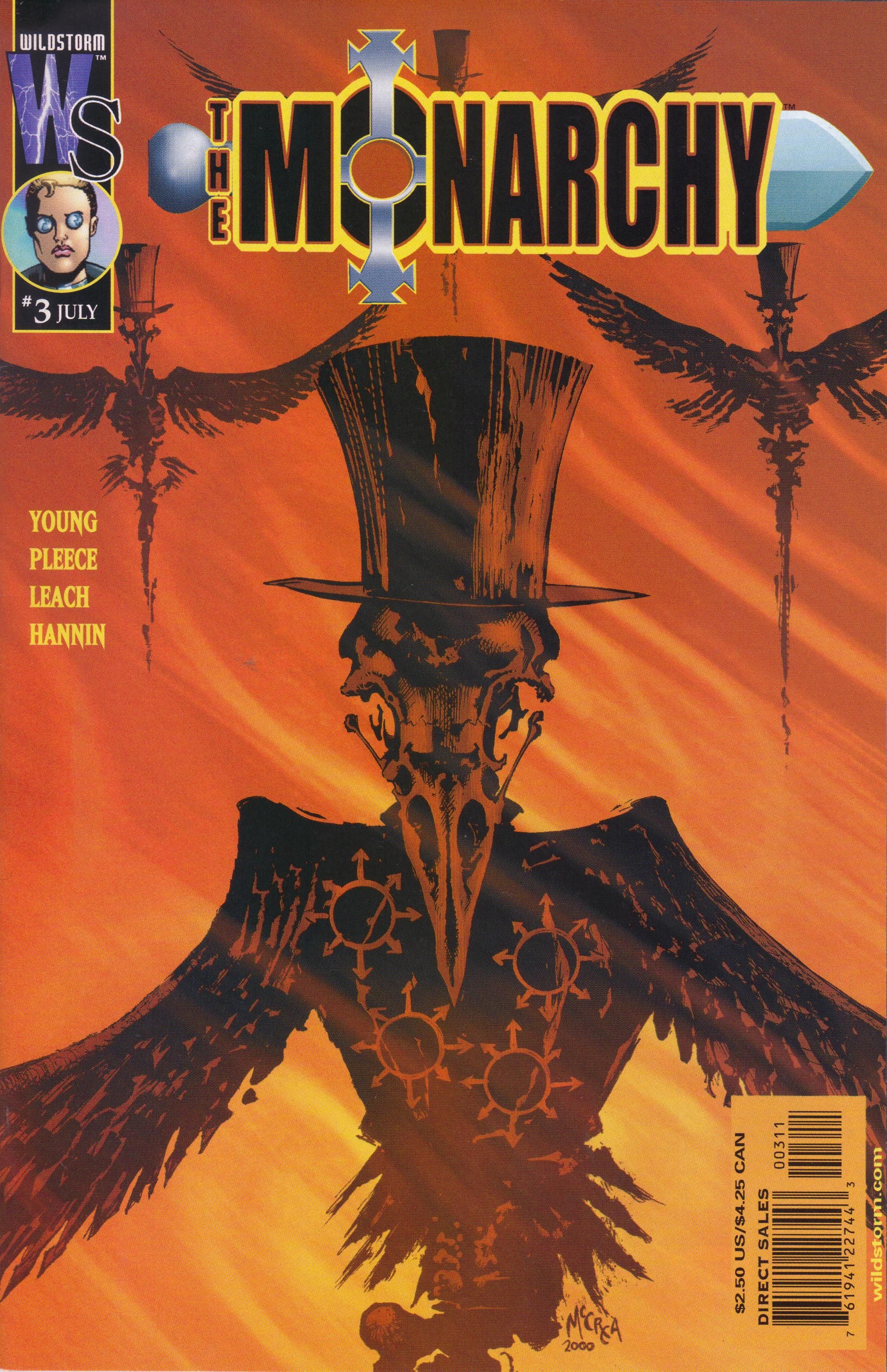

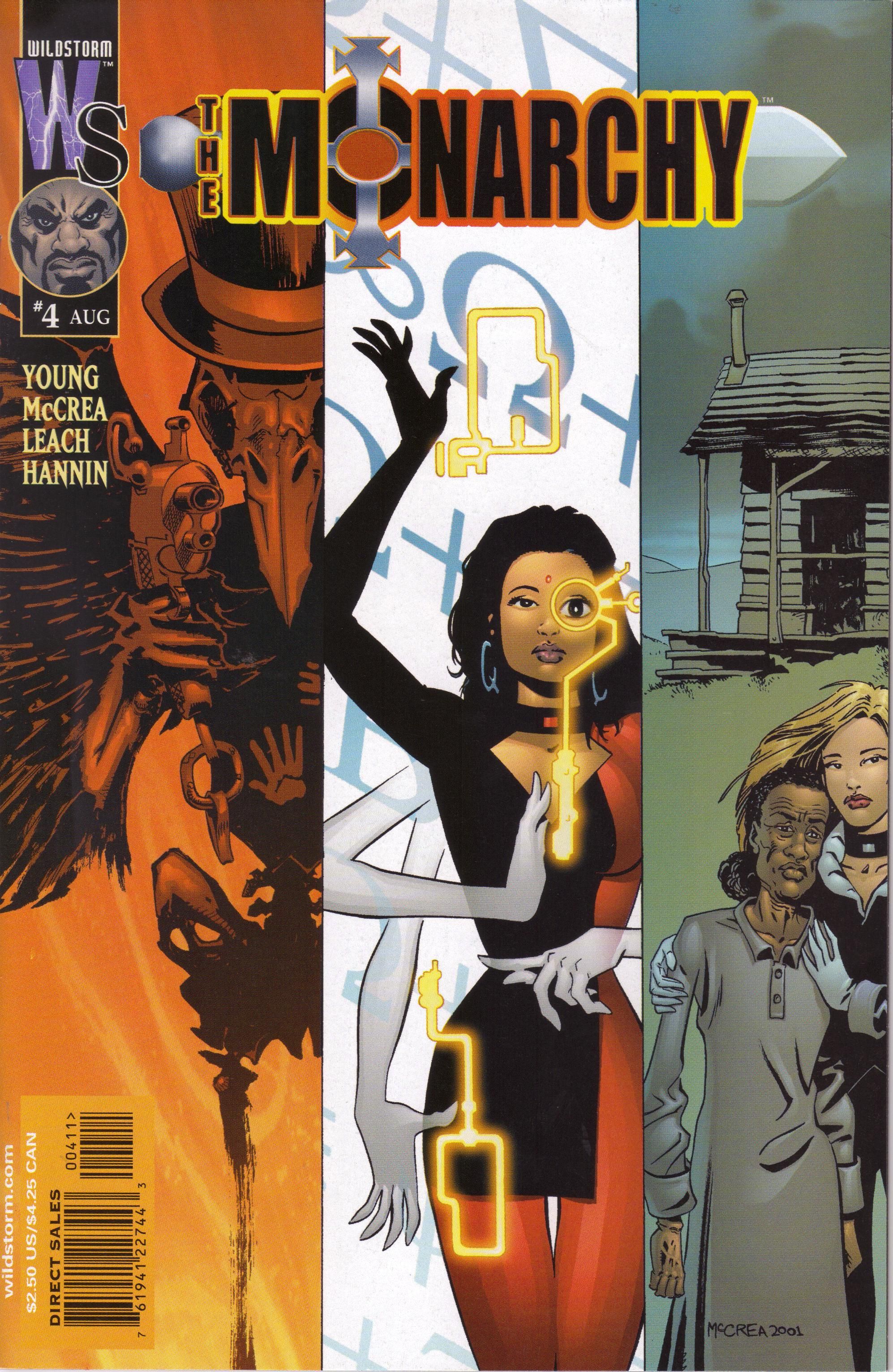

The Monarchy by Doselle Young (writer), John McCrea (penciler, The Authority #21; issues #1-2, 4, 6-12), Warren Pleece (penciler, issue #3), Dean Ormstom (artist, issue #5), Garry Leach (inker, The Authority #21, issues #1-4, 6-12), Ian Hannin (colorist, The Authority #21; issues #1, 3-5, 10-12), Wildstorm FX (colorist, issues #2, 5-9, 11), Naghmeh Zand (letterer, The Authority #21), Bill O'Neil (letterer, issue #1), Ryan Cline (letterer, issues #2-3), Jenna Garcia (letterer, issue #3), and Pearle at Fishbrain (letterer, issues #4-12).

DC/Wildstorm, 13 issues (The Authority #21 and #1-12), cover dated February 2001 - May 2002.

This post is slightly less comprehensive than I want it to be because I wanted to avoid too many SPOILERS, but some are in here. I leave the final, big one for you to discover, though.

In some alternate universe, comics like The Monarchy are beacons, lighting the way to a different way to view superheroes. It stands on the shoulders of something like Flex Mentallo and supports other comics, examining the superhero paradigm from myriad angles, giving readers varying and complex ideas about myths and how they interact with the world. In our world, The Monarchy is a mostly-forgotten footnote, a comic struggling feebly against a new wave, drowning in an ocean of "widescreen action." Like many failed comics, it came out as precisely the wrong time, and moreover, its writer dared to poke the bear, so it could not last. But it's a glorious failure, and very much worth a read.

If we accept the opinion of the pundits who pontificated on the end of Wildstorm, the imprint's Golden Age was 1998-2002.

In that time, readers got Warren Ellis and Tom Raney's StormWatch (issue #37, his first, is cover dated July 1996, a bit before this, but the second volume is cover dated October 1997 - September 1998); Scott Lobdell and Travis Charest's Wildcats (March 1999 - March 2000); Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill's The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen volumes 1 and 2 (March 1999 - September 2000; September 2002 - November 2003); Ellis and John Cassaday's Planetary (April 1999 - December 2009); Ellis and Bryan Hitch's The Authority (May 1999 - April 2000); Moore's Tom Strong (June 1999 - May 2006); Moore and J. H. Williams III's Promethea (August 1999 - April 2005); Moore and Gene Ha's Top 10 (September 1999 - October 2001); Joe Casey and Sean Phillips's Wildcats (April 2000 - December 2001); Mark Millar and Frank Quitely's The Authority (May 2000 - January 2001); Casey and Ashley Woods's Automatic Kafka (September 2002 - July 2003); Casey's Wildcats 3.0 (October 2002 - October 2004); Ellis's Global Frequency (December 2002 - August 2004) ... and a bunch of others I'm sure I'm forgetting. Still, that's a lot of quality comics, and except for the first Ellis run on StormWatch, all the titles burst onto the scene when DC acquired the imprint, which was effective at the beginning of 1999. This period was very influential on comics as a whole, especially Ellis and then Millar on The Authority (and StormWatch before it), as it took superheroes to a new level of action and involvement in political affairs and, with Bryan Hitch's expansive artwork, gave us "widescreen comics" that Marvel later co-opted with Millar and Hitch's The Ultimates, which was basically The Authority with Marvel characters (considering how Millar skewered the Avengers during his run on The Authority, he must have been laughing all the way to the bank). For those brief years, Wildstorm could do very little wrong, and then DC did some silly things: They censored Mark Millar's storyline in The Authority, and they blinked when Alan Moore used an actual olde-tyme advertisement in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen that Marvel might have objected to. They drove Millar into the arms of Marvel, where he became probably the only person in comics who has anything close to "Fuck Fame," and it drove Alan Moore into the latest of his northern English funks, where he resides today. But the creators spread to the Big Two and changed comics ... mainly for the better.

But let's consider The Monarchy and what it says about the biggest influence from this time period and how, maybe, it could have been different. Not necessarily better, just different.

Doselle Young's series will not appeal to people from outside the insular comics world. It requires a fairly decent understanding of The Authority, for instance, as it is a direct critique of that series. It also references StormWatch, and it also concerns the general idea of superheroes. It's not as much a deconstruction of superheroes as it is a commentary on what superheroes were becoming and, in some ways, remain - the idea of superheroes as revolutionaries, destroying the status quo and setting up a new one. Young goes after this idea, and therefore we might believe that The Monarchy - even its name smacks of conservatism! - is a return to a simpler, rigid, formulaic superheroic ideal (for instance, many characters speak of finding their niche, which implies that they mustn't move outside of that niche). Young has more on his mind than that, however, and forms his critique of superheroes by giving us a group who is less cynical than the Authority but just as willing to upend things to get the job done. Their job, however, isn't taking out tinpot dictators and getting in "pissing matches" with the president of the United States, as the Engineer accuses Jack Hawksmoor of doing in The Authority #21, which acts as an important prelude to the regular series. Jackson King, leader of the group, has a bigger agenda - protecting reality itself. So Young aims higher, fails (perhaps) more spectacularly, but also succeeds more wonderfully. While Mark Millar was showing what happens when superheroes become rock stars, Young was showing what superheroes are truly capable of. He pushed the envelope even further, and it makes the book's failure a bit more depressing.

Plot-wise, The Monarchy is fairly simplistic. Jackson King discovers that reality is sick and he needs to form a team to perform surgery on it.

King is the ex-Weatherman (the leader) of StormWatch, the superhero strike force that Ellis ripped apart so he could create The Authority. King does not get along with the members of the Authority, and after an odd event on board the Authority's Carrier in issue #21 of that series, he realizes that things are off-kilter in the universe and no one is doing anything about it. So he collects a bunch of superheroes - ones who have very unique positions in reality - and forms a team. They fix the universe, and all is well. Then the book got cancelled. It's a shame, but at least the 13 issues that do exist (The Authority #21 is by the same creative team as the regular series, and while it's still very much about the titular group, it also sows the seeds for the series and is important to read) form a complete story. If Young seems to take his time getting to the point, we have to remember that he was writing an ongoing, so it's not hard to believe that he was laying a foundation for many issues to come. That he ties off so many plot threads in the final arc is fairly impressive when we consider the scope of the earlier issues.

It's probably because of Young's meandering style that the book lost readers before he could pull everything together (it's certainly where he lost me; I actually bought it through issue #9, then dropped it, only getting the final three issues recently, after Chad wrote about it and piqued my interest), but reading it as a 13-issue epic, it's handled very well. Consider Jon Farmer, the superhero from "C-Space" who is sent into the Bleed by King One in the first few pages of issue #1.

We've already seen him, as the bartender in The Authority #21, who is somehow awakened by whatever wakes up Jackson. The Authority #21, in fact, is the most confusing issue in the run - during a conversation between the Doctor of the Authority and to the Engineer, the Doctor makes a bunch of butterflies that flit throughout the Carrier. These butterflies somehow change people - Union, an old StormWatch hero, shoots himself in the head with a gun formed from his "Justice Staff" (boy, an actor in a superhero porn parody could have some fun with that); Christine Trelane has what appears to be a seizure, Jackson King starts hearing the voices of Henry Bendix and his father (both deceased) in his head; and Farmer shoots rainbows out of his eyes. We have absolutely no idea what's going on, and Young allows these questions to fester in our heads for some time. In The Monarchy #1, King One shoots Farmer through a prism, apparently imbuing him with power. When next we see him he's pretending to be a priest in Philadelphia, and Christine Trelane lets us know that it's been six months since the "incident on the Carrier." It's only at the very end of the issue that Farmer uses his "rainbow power" and we get confirmation that he was the bartender. Why does this circuitous route to answers matter? Because Young does this constantly, dropping hints throughout the run and bringing them back around later on, sometimes confirming what we guess, sometimes revealing new information. As a serial, The Monarchy is frustrating because of this oblique storytelling style.

But Young himself tells us that's how it's going to be: King One sends Farmer through a prism, shattering him into pieces (which we see on the splash page of the first issue), and later, in issue #9, Farmer tells Abraham Dusk that accepting the ancient god that Jackson King uploaded into his consciousness is like passing through a prism. Each discrete piece comes together to form a whole, working in perfect harmony like light from a prism that has been splintered into its components but still makes a white blaze.

Young does this with every part of the series, especially early on. In The Authority #21, Jackson picks up Union's "Justice Stone" and resurrects him, but Young doesn't give us any more information about what the stone is (again, this is a failing of the introductory issue - this is old information, but only to someone who had read StormWatch and its spin-offs), and we only learn that King and Trelane resurrected him in issue #2. Union gets the spotlight in issue #2, as he looks for a "Kheran dream-engine," a device which ends up playing a very important part of the final arc but takes its time getting to where it needs to get. In issue #3, King sells the ghost of Hitler to some nasty aliens (who wear nice suits and ties) for something that doesn't show up again until issue #10, but it doesn't become significant until the final issue. We meet Agent Morro in issue #2, but he doesn't show up again until issue #6 and we don't learn his place in the grand scheme of things until #11. And then there's Henry Bendix, the old Weatherman of StormWatch. Bendix was famously killed by Jenny Sparks in that comic, but Young shows us his "origin story" in issue #5 and resurrects him in issue #11.

He does this for two reasons: one of his major themes is change, either from death to life or from one stage of consciousness to another, so the fact that he brings Bendix back isn't too surprising; and because critiquing the Authority and their form of superheroics underlies the entire run, bringing Bendix back and rehabilitating him is crucial to that criticism.

As we've seen, Union shoots himself and comes back. Young returns to the idea of "death/resurrection/transformation" all the time, culminating with Jackson King himself. Christine Trelane, Jackson's lover-then-wife, is transformed on the Carrier into the queen of origin stories (an extension of her old power, which is activating latent superhumans). This remains a vague power, but she is able to turn people from the morally compromised characters they may have become into something purer. As Jackson says to Farmer in issue #1, "even our origin stories are going sour." The world needs the Monarchy and Trelane to set things right. She is able to turn Addie Vochs, a forgotten "century baby" - an idea that Warren Ellis made popular with Jenny Sparks and Elijah Snow - into the force she was supposed to be. She gives Arlo Scheer, the man who wants to pilot a blimp filled with explosives into a city, a second chance because she can tell he's not a bad guy, just a misguided one. She gets Malcolm King, Jackson's brother, where he needs to be to help them in their fight. As we learn in issue #12, she introduced Jackson to the Weavers, who had been watching over Henry Bendix and were now assisting the Monarchy. And she helps Matt, the kid whose origin story went horribly wrong in issue #1, become a true hero.

We have other transformations in the series, too: the aforementioned Addie Vochs, whose place as a century baby was hijacked by the Fevermen, "living manifestations of humankind's willing enslavement to fear," according to Bendix; Abraham Dusk, whose origin story didn't work out precisely the way he wanted it to but who gets a second chance when Jackson implants a native god into his consciousness; Malcolm King, who is redeemed in this series after years in a sanitorium; and Jon Farmer, who mirrors Jackson's death and resurrection in his own way. All of these transformative moments and what the characters become - Dusk becomes the Metropolitan and Malcolm becomes Bellerophon, each created for a specific moment in their battle - help with the climax of the series. Then there's Jackson King, who is killed at the end of issue #8. We're fairly certain the death won't last, but as we learn in the final arc, his death was necessary for him to become "imaginary" - pure force of will. According to Young, that's exactly what happened to him when Jenny Sparks killed him. Only then can he and Jackson confront the disease threatening reality.

Young's picking at the fabric of the Authority makes up a great deal of the series, as well. It may have been this that contributed to the series' demise - Young was going after Mark Millar at the precise moment he was on the ascendant, and it probably wasn't the smartest thing to do, career-wise. Mainly, Young points out that the Authority's way of doing things causes problems because they are no longer heroes worthy of praise, and Jackson has a better way.

Young first brings this up in The Authority #21, but in that issue, it's limited to Jackson ranting at Hawksmoor and whining a lot. In issue #1 of the regular series, we see what happens when "origin stories go sour" - Matt has gained radioactive powers and his friends are using him to gain powers. Their leader, Jenni (who wears a Jenny Sparks tank top), leads them on a campaign to kill homeless people, because it's her twisted vision of making the world better, like her heroes in the Authority. The warped purity of Jenny Sparks' and Jack Hawksmoor's mission is the impetus to Jackson's response. As the series goes on, this oppositional viewpoint of Jackson's becomes much more important. While The Authority under Ellis was slightly more hopeful, under Millar it became far more cynical and self-satisfied. Young shows that there is another way. Even though the final arc (which I don't want to spoil, because it's neat) turns into a big fight, it feels like that's more because Young had to wrap up the series rather than what he really wanted to do. Everything prior to that indicates that he would be more subtle than what happened, contrasting once again the brutal "realism" of the Authority with Bendix's visionary melding of science and fiction. Everything but the very resolution of the conflict points to this. Throughout the run, The Monarchy is tremendously hopeful comic. Condition Red uses a spirit-gun to heal people, not to kill them. Professor Q, despite appearing to be the most unemotional of the group, helps Addie adjust to her new reality. And, of course, the series ends "over the rainbow" - earlier in the series (in issue #4, to be precise), Farmer, not surprisingly given his power, tells Union he witnessed the fall of Oz, but the series ends with a "new Oz," created partially by Farmer himself. Many series end on a hopeful note, but occasionally it feels false or unearned. Young never lets his heroes turn to cynicism, so the ending feels absolutely perfect, even though Young may have rushed to it sooner than he wanted to.

Many people have complained about John McCrea's art on the series, but I am not one of them. Warren Pleece's art is enough like McCrea's in issue #3 (Leach and Hannin might have something to do with that) that we don't have to consider it, but Ormston's in issue #5 offers an idea of what the book might have looked like if someone less like McCrea had drawn it.

While Ormston's art works for the story of Bendix, which is slightly more Gothic-horror than the rest of the book, his journey with Bendix into the fantastical world of Panacia is, unfortunately, not as wacky as McCrea would make it. Why is this "wackiness" important? Young is not dealing with realism, and McCrea's often humorous art adds a nice level of levity to the series, never allowing Young or the reader to take himself too seriously. Even when Young deals with serious topics, McCrea's cartoonish and deceptively simple art (it's actually very detailed and precise) helps from it becoming too dour - which is what Young, eventually, is going for. The story needs a serious tone every once in a while, but an overall theme of the series is the power of fantasy, and McCrea always reminds us of that, from the goofiness of Abraham Dusk's "secret origin" to the twisted weirdness of the Fevermen to the final glorious battle on a strange and magical world. Young is dealing with bright and shiny heroes showing a way toward an optimistic future, and a more serious artist would have cut across that tone far too much. McCrea, while more perfect on something even more outlandish like Hitman, fits this series far more than many people admit.

The deck was stacked against The Monarchy, but it's stacked against a lot of new series, and even though Young didn't get to tell his entire story, he did tell a significant one, and it shouldn't be ignored. As I wrote above, The Monarchy is the spiritual successor to Flex Mentallo, another comic whose messages were largely ignored.

It's good to have these comics, because they point to a different understanding of what it means to be a superhero, and it's always good to have different points of view about what heroes can accomplish and the methods they use in accomplishing those things. It's somewhat cowardly of Wildstorm and DC that they allowed this entire run to be retconned out of existence (Jackson King was apparently on acid for year, a retcon that, frankly, doesn't even deserve consideration), but that doesn't change the fact that these issues exist, and they form a very cool story that works on its own, even though it's a bit more clever if you've read some of the comics it references. Young's idea of superheroes solving problems differently than by punching them isn't unique, but it is attempted far too infrequently and it usually doesn't last. When a creator gets it right, however, it's brilliant reading. If you started The Monarchy and ditched it because it was too confusing (as I pointed out above, I sympathize), now's the time to give it another try. There's a trade collecting The Authority #21 and the first four issues of the regular series, but the rest of the series is uncollected. However, it's fairly easy to find and fairly cheap to buy, so I would encourage you to hunt it down. It definitely reads better in one big blast rather than in monthly serials, and when we read it in that way, we can appreciate what Young was doing. When we read it with almost a decade of hindsight and see the way superheroes have evolved, it becomes much more interesting, as well. We can always use more thoughtful takes on superheroes, can't we?

As usual, you can cruise through the archives if you wish!