Man, it's hard to write about Planetary. So many others have already done so! But I'll give it the old college try, just for you guys. I love you guys so much!

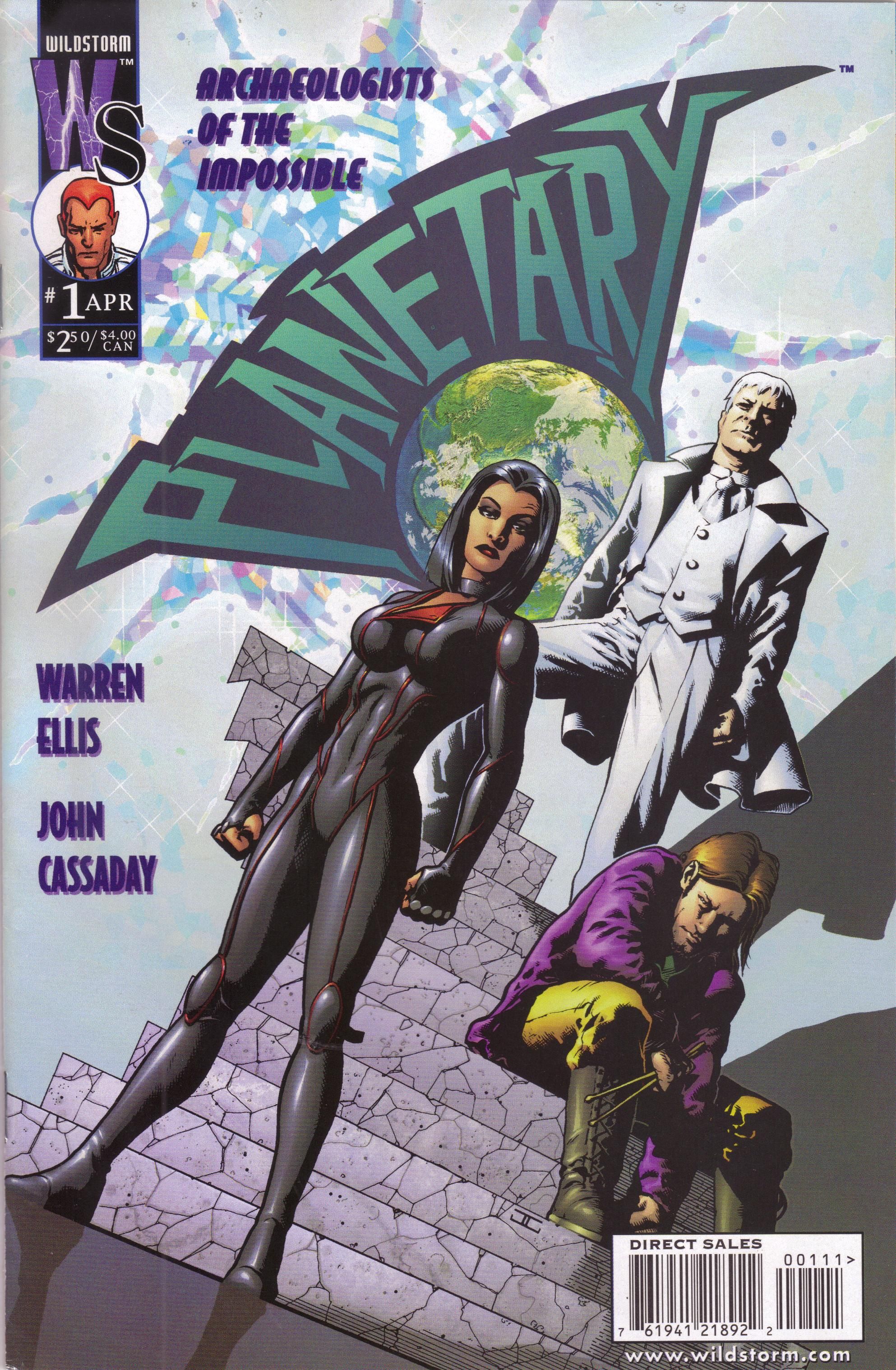

Planetary by Warren Ellis (writer), John Cassaday (artist, issues #1-27 and Planetary/Batman: Night on Earth), Phil Jimenez (penciller, Planetary/The Authority: Ruling the World), Andy Lanning (inker, Planetary/The Authority: Ruling the World), Jerry Ordway (artist, Planetary/JLA: Terra Occulta), Laura Martin (née DePuy) (colorist, issues #1-6, 8, 10-27 and Planetary/The Authority: Ruling the World), David Baron (colorist, issues #3, 6-7, 9-10, Planetary/JLA: Terra Occulta, and Planetary/Batman: Night on Earth), Bill O'Neil (letterer, issues #1-2, 11-15), Ali Fuchs (letterer, issues #3-6), Ryan Cline (letterer, issues #7-8, 10 and Planetary/The Authority: Ruling the World), Mike Heisler (letterer, issue #9 and Planetary/JLA: Terra Occulta), Richard Starkings (letterer, issues #16-27), and Wes Abbott (letterer, Planetary/Batman: Night on Earth).

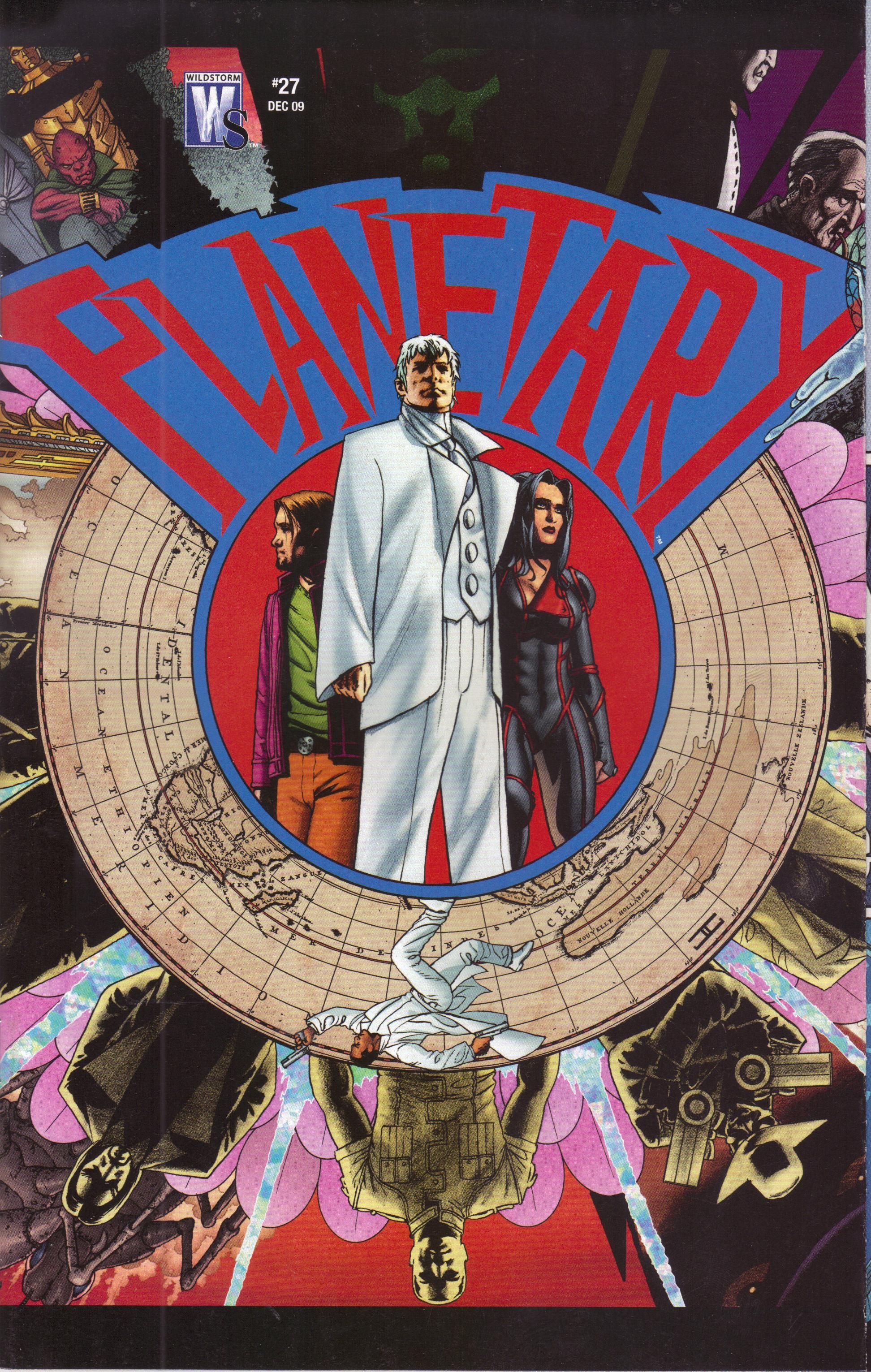

Published by DC/Wildstorm, 30 issues (#1-27 of the ongoing series, plus Planetary/The Authority: Ruling the World, which comes between issues #10 and 11, Planetary/JLA: Terra Occulta, which comes after issue #15, and Planetary/Batman: Night on Earth, which comes after Terra Occulta), cover dated April 1999 - December 2009.

Ah, yes, the obligatory SPOILERS AHOY! warning. There it is! And, as always, click the images (well, most of them) to enlarge them!

Planetary is a masterpiece. It's Warren Ellis's magnum opus (some might argue for Transmetropolitan, but I won't) and it's one of the best long-form comics ever. Yes, ever. It doesn't quite reach the levels of Morrison and Case's Doom Patrol, but it's up there with Ennis and McCrea's Hitman, in the rare air that most creators strive to achieve but never do.

I'm not sure if Planetary gets the recognition it deserves, and that's too bad. It's brilliant, and it deserves to be read over and over, because it will always surprise and excite you. Unless you have no soul, that is. You have a soul, don't you?

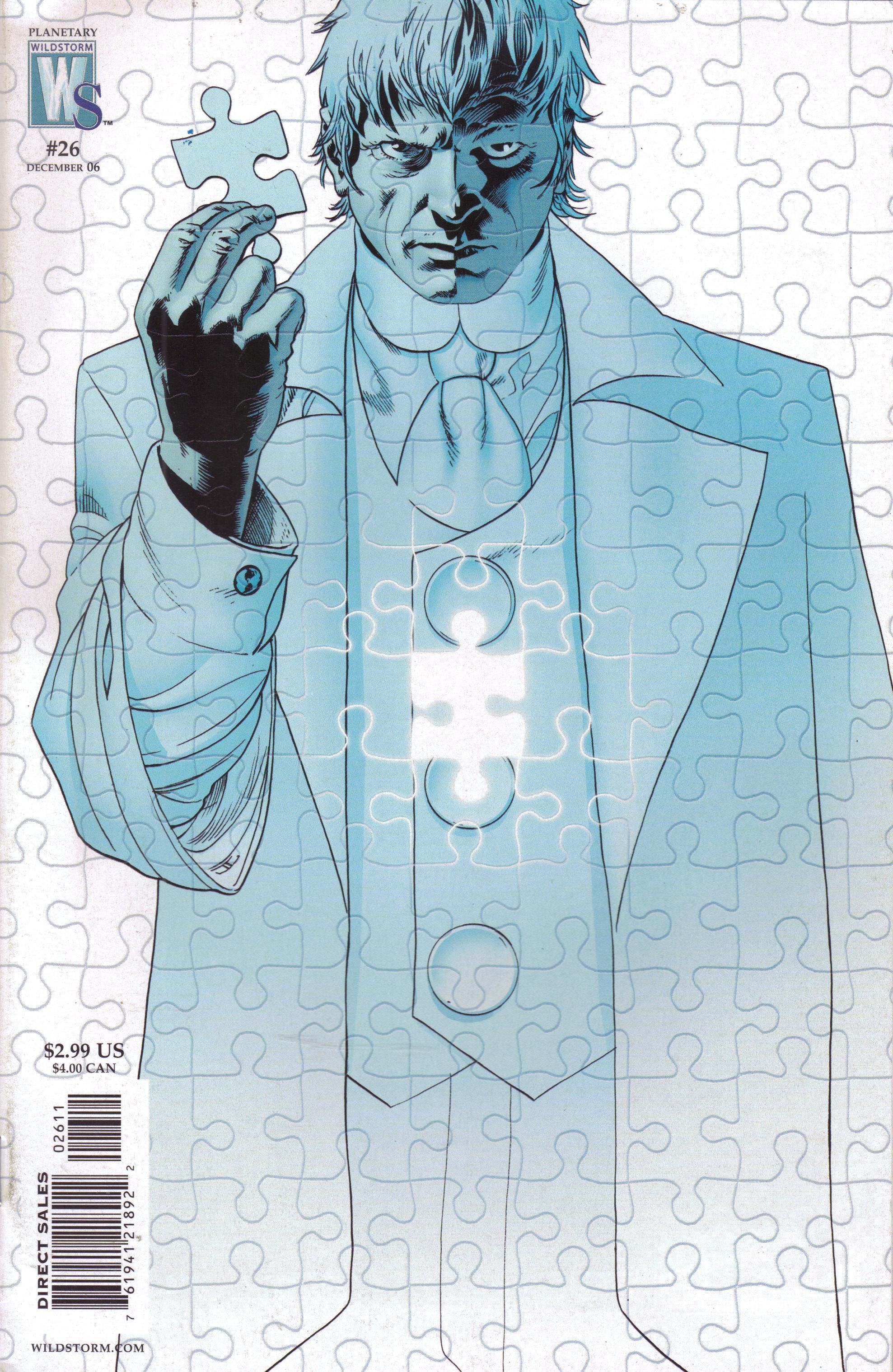

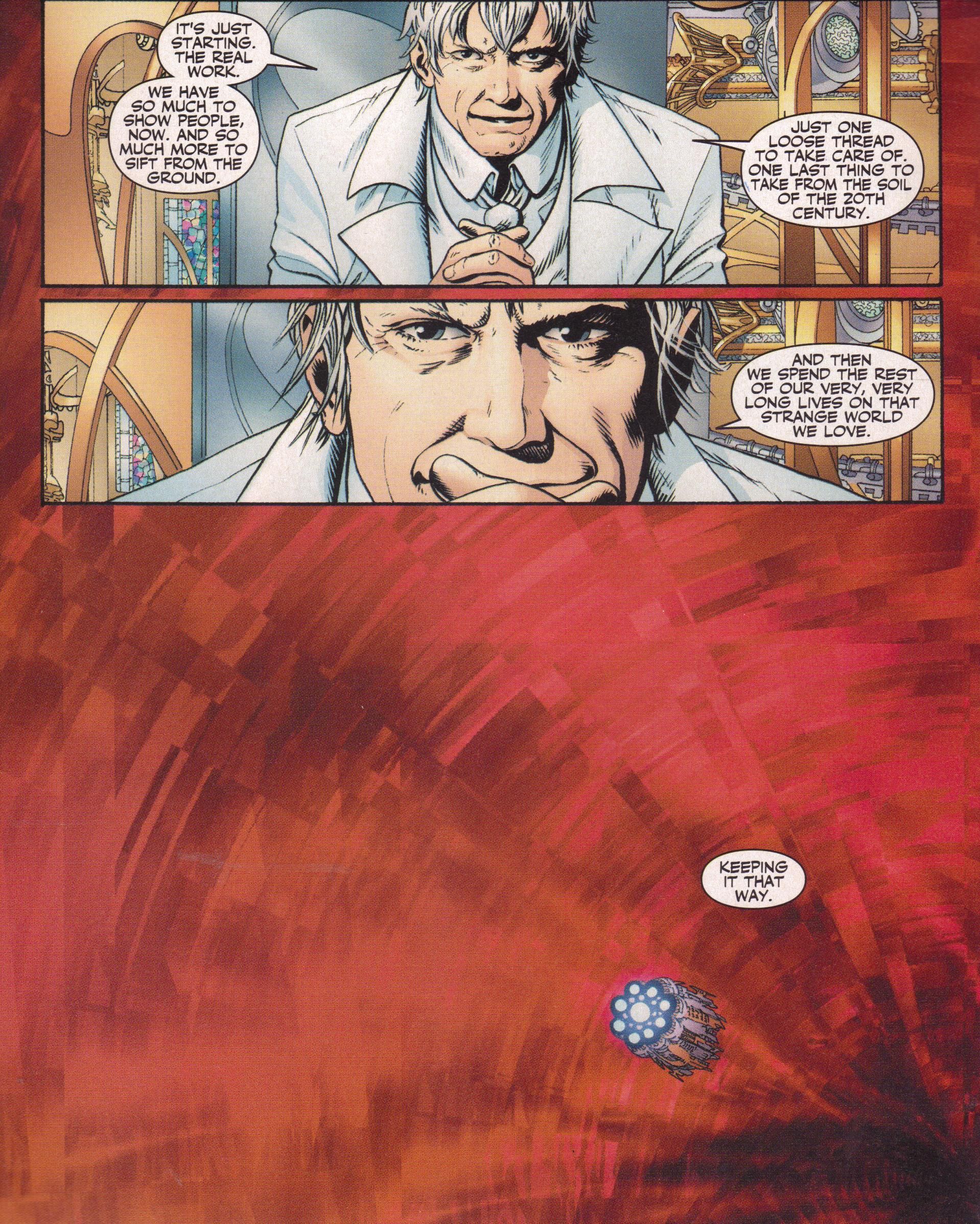

Ellis has often written angry, cynical comics full of bastards, but he's kind of an old softie at heart. Nowhere is this more evident than in Planetary, which is all about hope. Sure, it's full of evil bastards, but there's never a sense that they will triumph. What Ellis does with Planetary (he did this with The Authority, too, but not to the degree he does here) is make it obvious that the good guys will win, but there's never a loss of tension within the narrative. In regular superhero comics, we know that the good guy will win, but writers often try their hardest to make sure we think they might fail. Ellis doesn't care about that. The only reason Elijah Snow and his group don't wipe the floor with the Four is because Snow is trying to regain his memory and he's not fully capable of going after them yet. Once he is, it's no contest. Ellis simply doesn't care about the superheroes-versus-supervillains paradigm that drives the vast majority of comic books (even today, in these enlightened times). Planetary isn't about that. What Planetary is about is right there on the cover of issue #1: "Archaeologists of the Impossible." That's a great tagline, and it explains a great deal of the book. Elijah Snow isn't about fighting, even though he does his share. In issue #26, when Jakita Wagner complains that in the final confrontation with Randall Dowling, she didn't get to hit anything. Elijah responds: "You're thinking like Dowling. Shoot something. Destroy something. That was his concept of power. Knowledge towards destruction. Me? I discovered and saved these people, located a lost ship of the Bleed and pulled it from its tomb. Archaeology." He's even more explicit in issue #24, when he talks of the function of century babies (those people in Ellis's Wildstorm universe who were born on 1 January 1900, which Snow was). Each of them has a function, and Snow's is to save people. He saved Jakita when the citizen of her birth city would have left her to die (she was the daughter of one of their black women and a white man), he saved The Drummer from Randall Dowling, and he saves Ambrose Chase from death.

Throughout the series, he saves people and things, and any bad guys he defeats is merely an afterthought. It's why Planetary is such a hopeful book and why it ends with Snow saving Ambrose Chase and not with Snow and his team defeating the Four. It's why Planetary is so much more interesting than almost anything Ellis has ever written (and he's written a lot of very good comics, don't get me wrong).

There's another fascinating subtext at work in Planetary. Perhaps it should go without saying that Ellis's main villains are the Fantastic Four, but what's unusual about the Four is that Ellis is not speculating that this is what would happen if Marvel's First Family were villains, he's stating explicitly that the Fantastic Four are villains as they currently exist in the Marvel Universe. The FF do exactly what the Four do - they accumulate esoteric knowledge and don't share it with the rest of the world. The vicissitudes of the Marvel Universe being what they are, no one at Marvel allows the fictional world their heroes inhabit drift too far from the "real" world, so all the fantastic inventions that Reed Richards and his ilk have come up with over the years are doled out piecemeal, and the Marvel Universe still doesn't have flying cars. This cognitive dissonance is the worst whenever Marvel tries to be "relevant" - the 9/11 issue of Amazing Spider-Man is the apex (or nadir) of this sort of thing - and the readers see behind the façade of "realism" that Marvel strives for (DC is a lesser example of this, as the DCU has never been predicated as much on the "real world" as the Marvel U. is). Planetary is not only Ellis's commentary on a variety of superhero tropes and Vertigo staples (in the notorious issue #7, when Jakita tells Snow that Margaret Thatcher was "genuinely mad"), but also the concentration of power in too few hands. In Planetary, Jenny Sparks and the Authority are almost villainous - Jakita remarks in Ruling the World that the Authority "fought off an invasion from a parallel earth, re-invaded that world and destroyed their ruling power in less than twenty-four hours."

When Planetary confronts the creatures in the Bleed, they are evil versions of the Authority. Even Planetary, in Terra Occulta, is the ruling power, and it's not a good thing. Ellis's healthy skepticism about the powerful, which manifests itself in many ways in his comics, is front and center in Planetary, but Elijah, Jakita, and The Drummer deal with it in the healthiest way possible - not by fighting (although they do plenty of that) but by consensus-building and excavating knowledge. Only that way can everyone be free, and Snow and the gang will strive to their dying breath to bring freedom to the world.

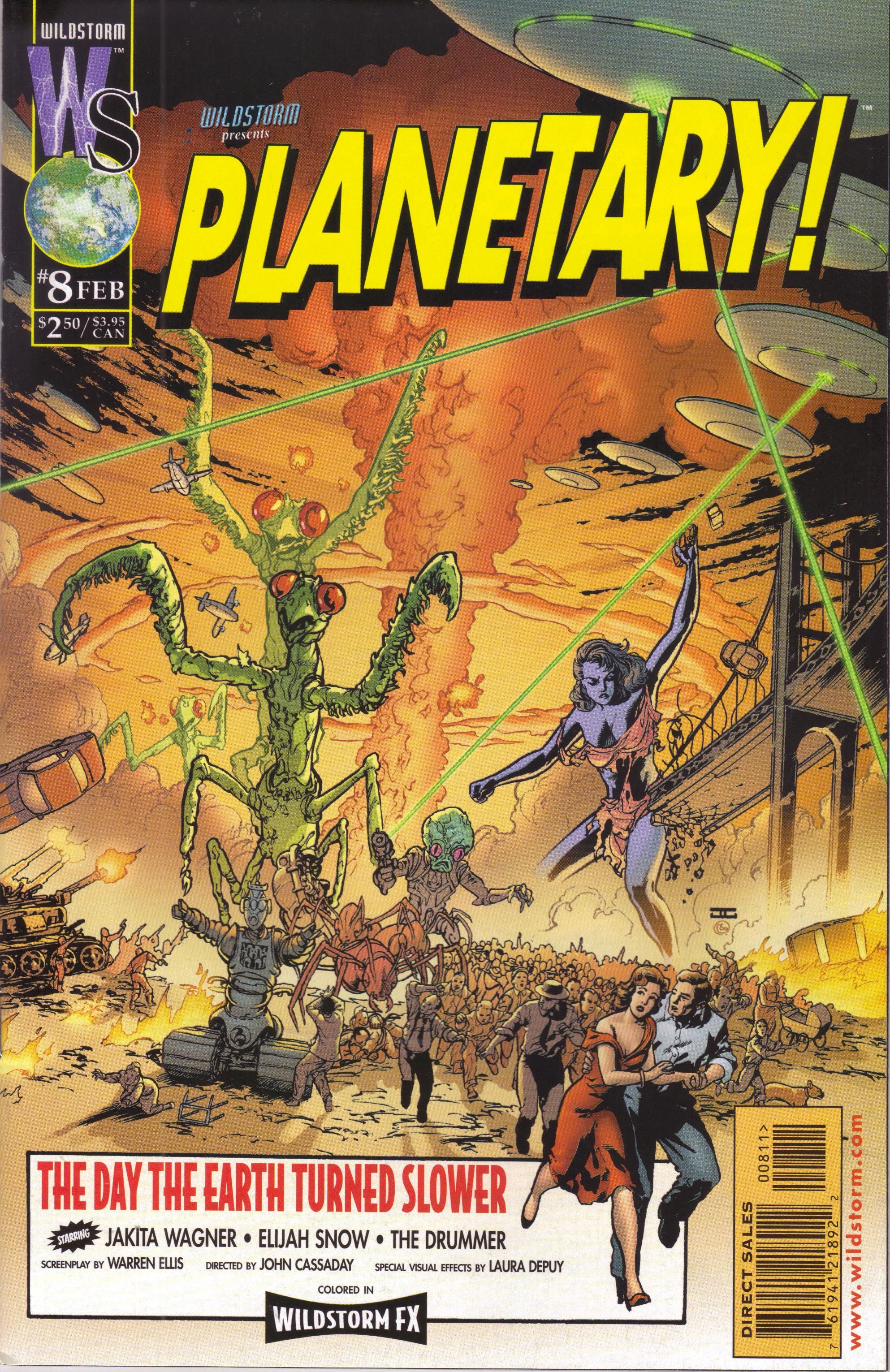

Planetary is so brilliant because it encompasses so much of comics history, and Ellis is smart enough to throw it all in the blender and see what happens. He never turns it into a parody of superhero comics - Jack Carter's victim in issue #7 is silly, but he's silly because Ellis is showing how silly "mature" comics are - but instead respects the way the genres he's using work, be it Westerns or pulps or monster movies or superhero books. Ellis has long been a fan of other genre fiction and has attempted to blend that with superhero books (with varying success), and Planetary is where it works the best. Ellis doesn't need to make superheroes mature, because he gets the wondrous stories of superheroes and how amazing they can be when a gifted writer gets a hold of them. It's astonishing that in one series he can skewer Marvel's first family so well yet give us a superb portrayal of Wonder Woman (even though the Four kill her). Early on in the series, before Ellis really began his mega-plot, we got some of the best single-issue stories of the past 15 years - Doc Brass and his shadow council discovering the snowflake in issue #1, the Monster Island story in issue #2, the ghost policeman in issue #3, the magnificent James Wilder story in issue #4, Jack Carter's death in issue #7, City Zero in issue #8, Planet Fiction in issue #9: All of these are informed by other diverse genres, from the pulps (issue #1) to John Woo movies (issue #3) to Grant Morrison (issue #9), and Ellis blends them marvelously to create his "strange world."

Even after the malevolence of the Four is revealed, we still get wonderful single issues like the Tarzan story (issue #17). Ellis brings these all together by the end, but you could easily pick up one of these issues and be treated to a brilliant story that doesn't require further reading (but why wouldn't you?). Ellis's mantra - "It's a strange world." "Let's keep it that way." - remains his ultimate priority, so he never forgets to show how bizarre the Wildstorm world is. This means the Lone Ranger, Sherlock Holmes, Dracula, the Shadow, Swamp Thing, and Superman all existed in the same universe, and Ellis makes sure that he ties them to each other nicely.

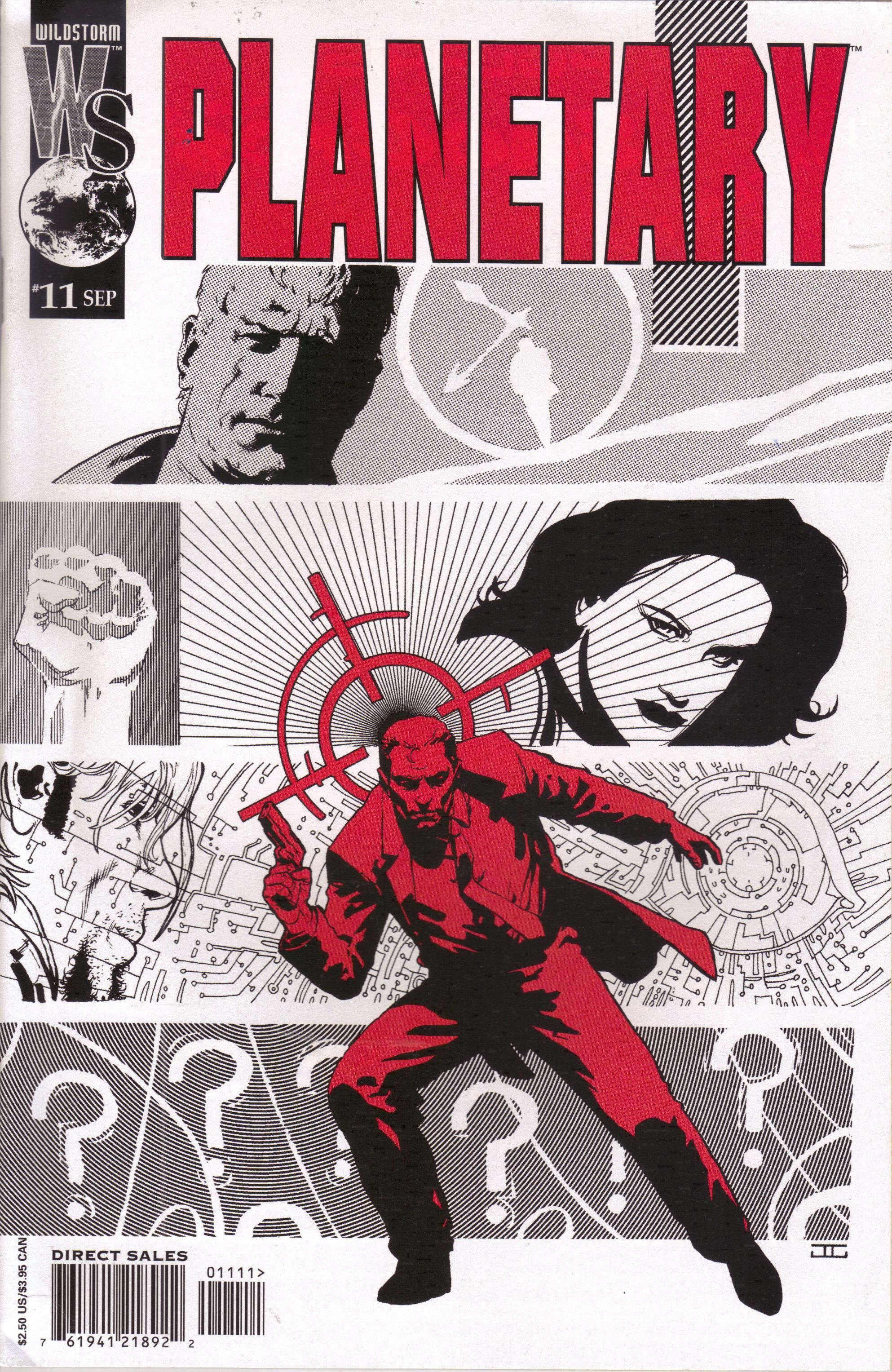

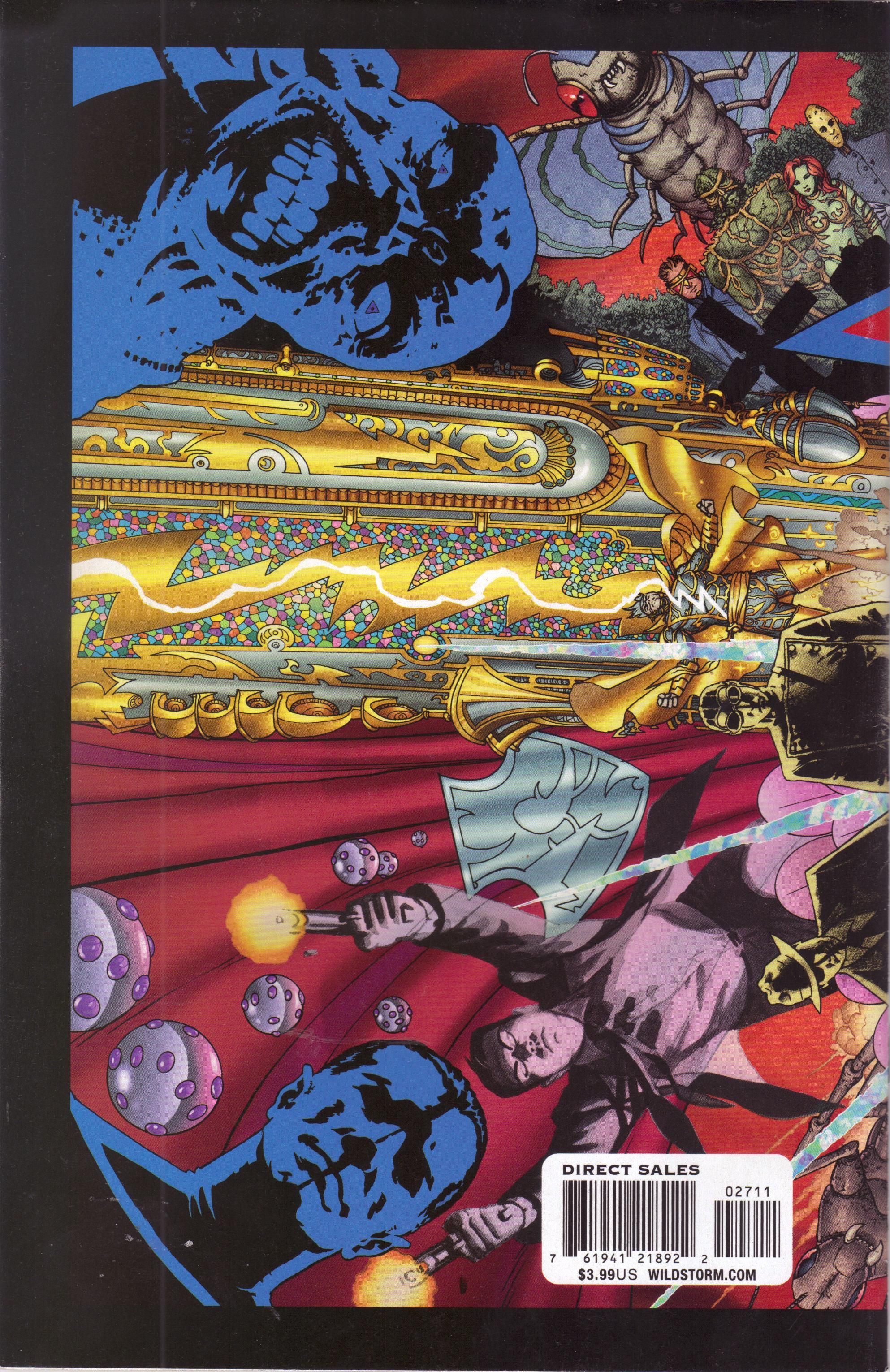

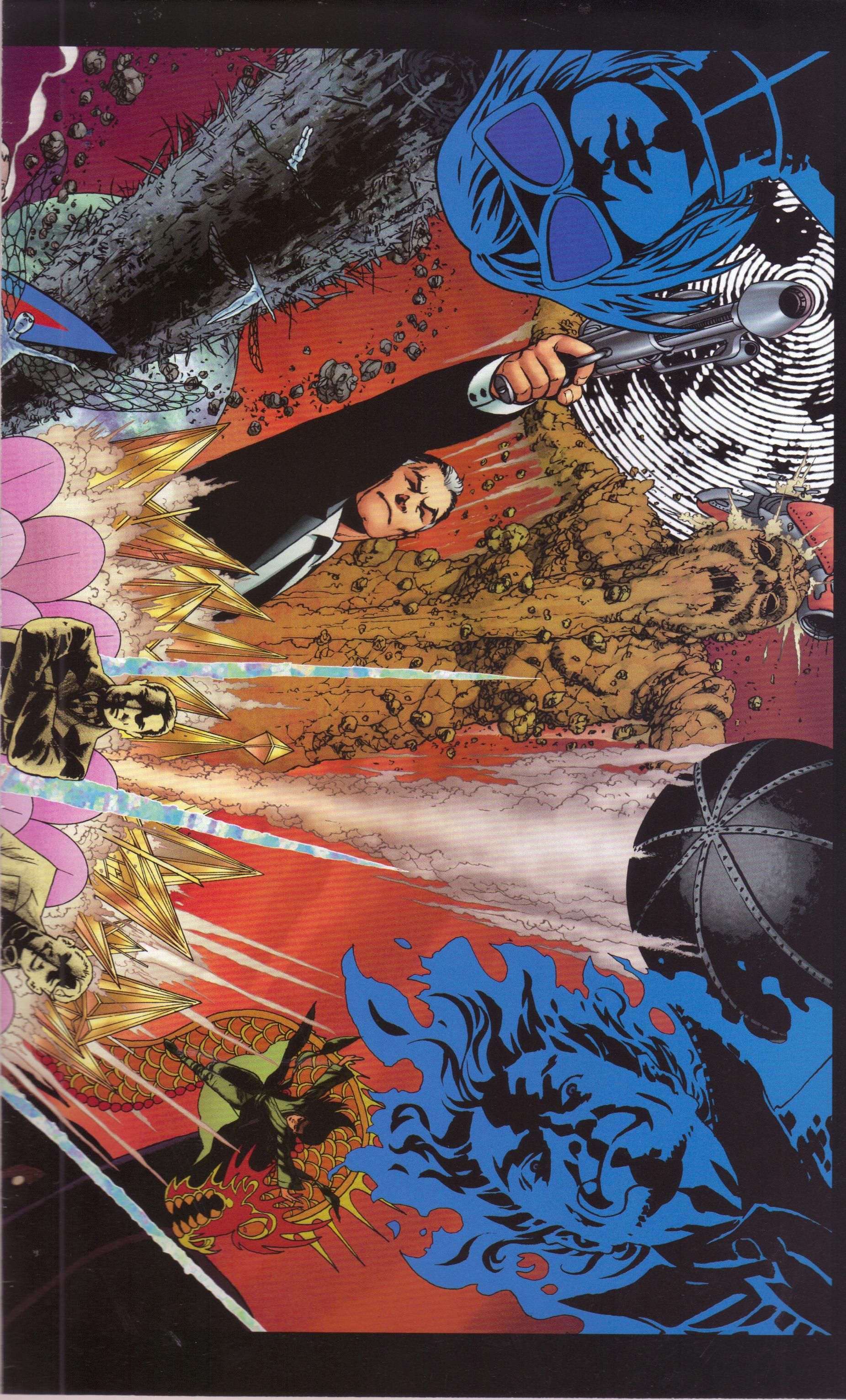

He couldn't do this without Cassaday's contribution, of course. Cassaday began this series as an artist on the rise and ended it a superstar who doesn't even need to do interiors anymore because his covers are in such demand. Cassaday's fine-line technique has its detractors, but in Planetary, he's magnificent ... and the perfect artist for Ellis's vision - his clean and precise lines show us a world of glory where another artist might sully it. Cassaday also manages the trick of showing a variety of characters from wildly different genres and doing it very well without really altering his style. He has to draw pulp heroes like "Doc Brass" (Doc Savage), "Bret Leather" (The Shadow), "Lord Blackstock" (Tarzan), and "Hark" (Fu Manchu); Godzilla-type monsters; the marvelous shiftship interior; plenty of science fiction; various Vertigo characters (John Constantine, Swamp Thing, Animal Man, Dream, and Death); Marilyn Monroe; a full page of "Green Lantern" aliens; a Steranko-esque spy story; a scene in Frankenstein's castle; a martial arts battle; and Batman in various stages of his history (among other things). He does all this without using new styles - it's unmistakably Cassaday - but by drawing the characters with just enough variation to make them his own but still being recognizable and, in some cases (issue #11, the Steranko homage), altering his page layouts just enough to ape the master. It's amazing stuff, and it's even more impressive when you consider that Cassaday (or perhaps Laura Martin) used computer effects not to the detriment of the final product (which far too many books do) but to enhance it.

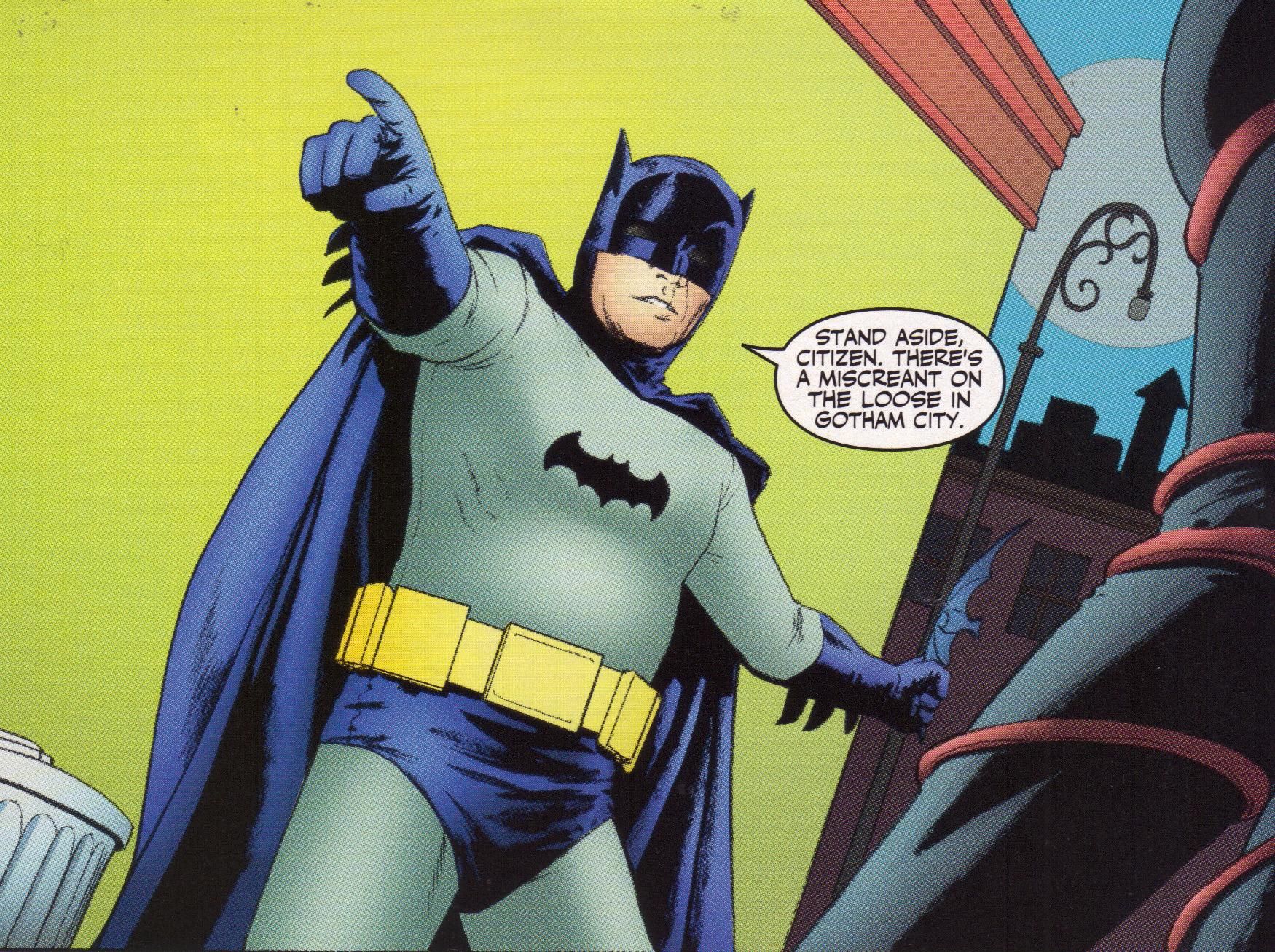

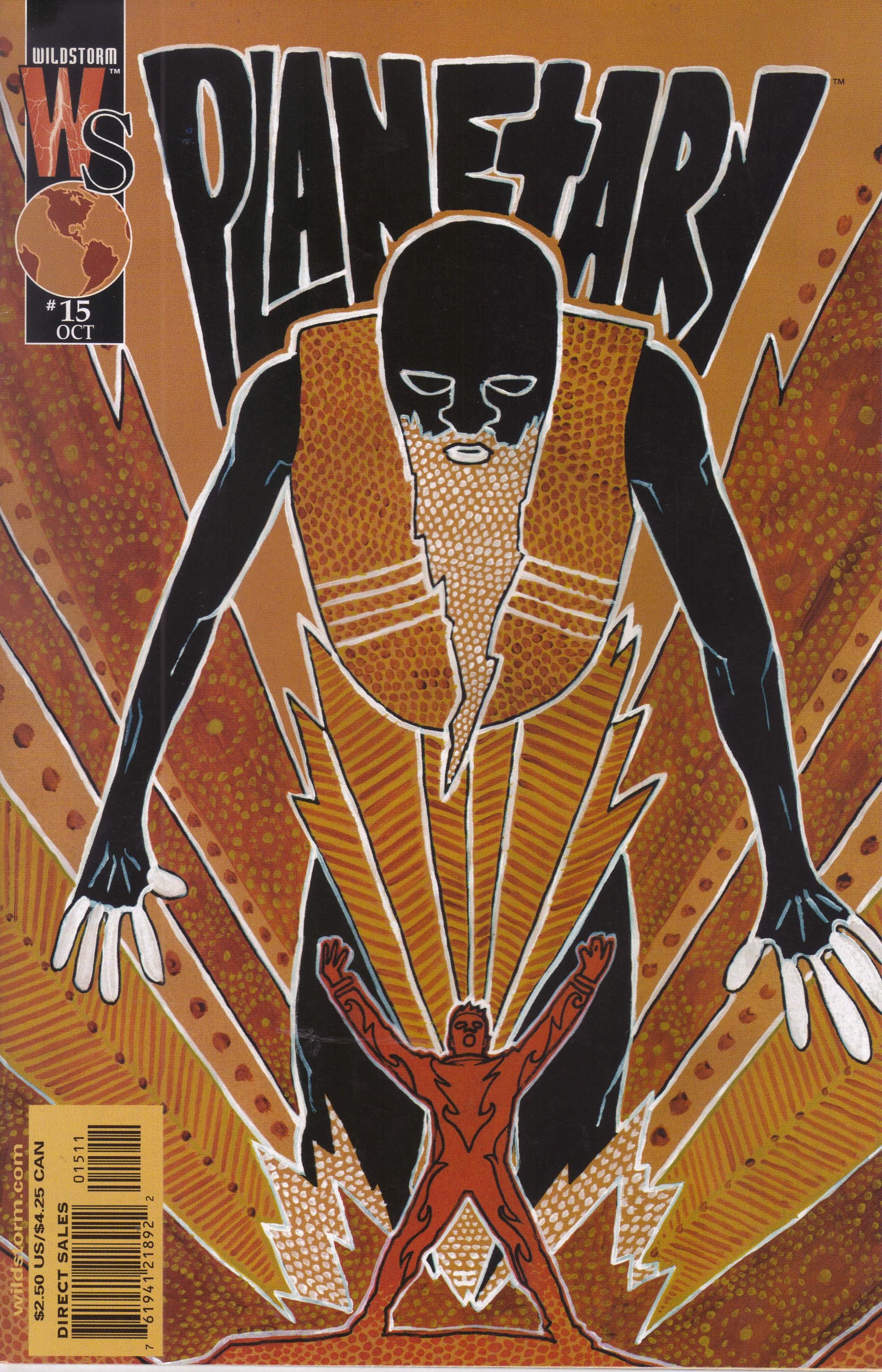

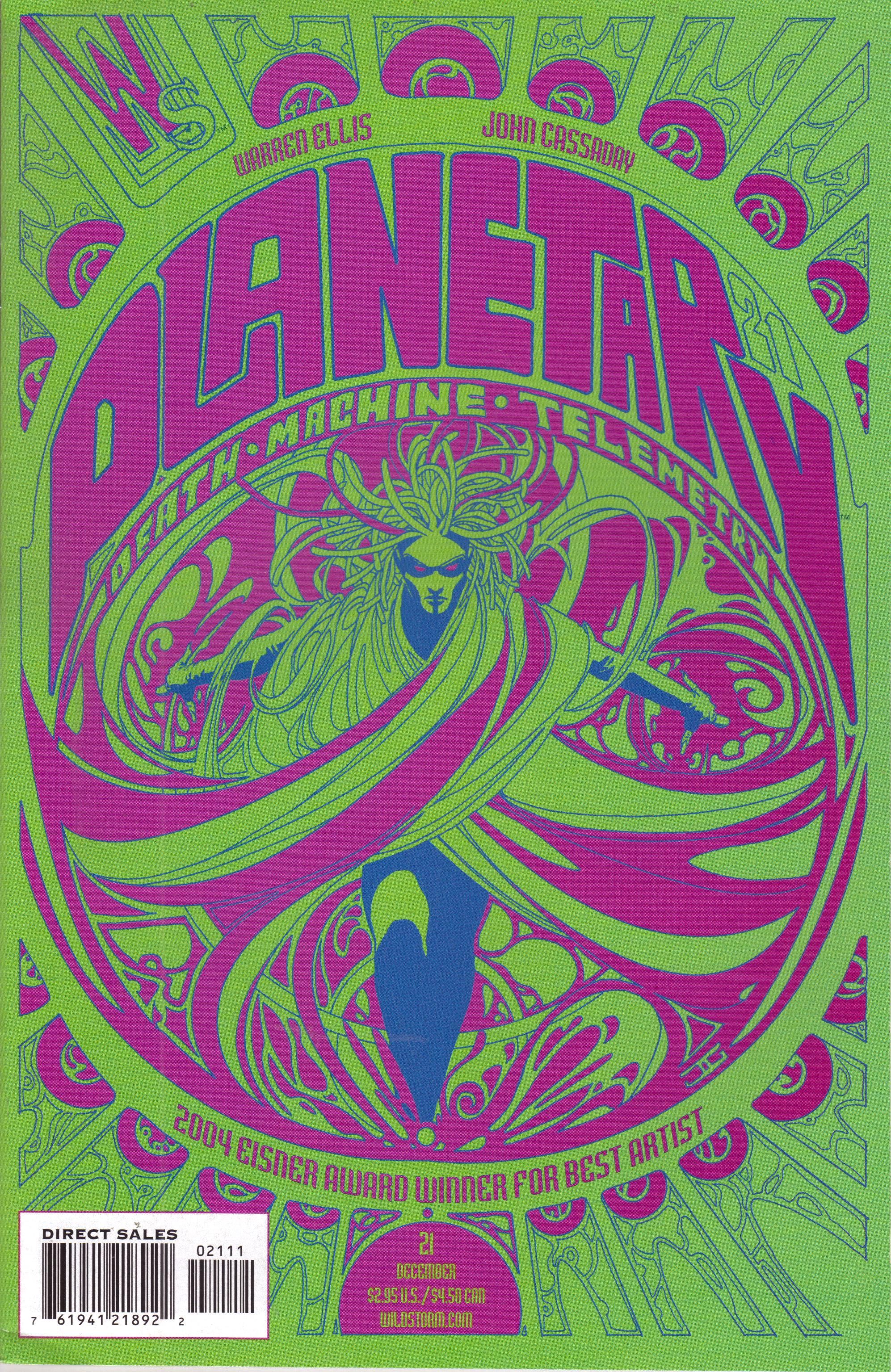

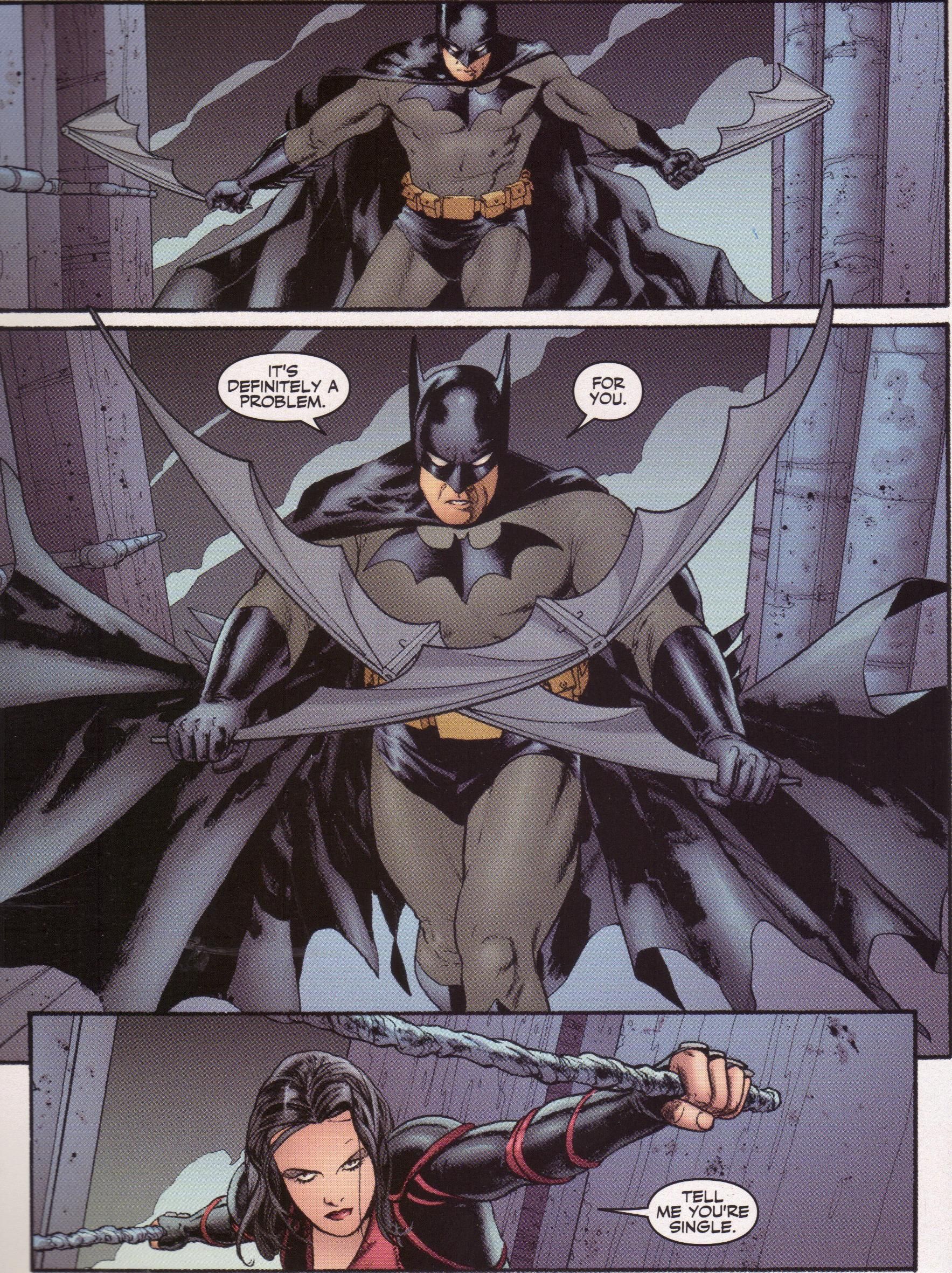

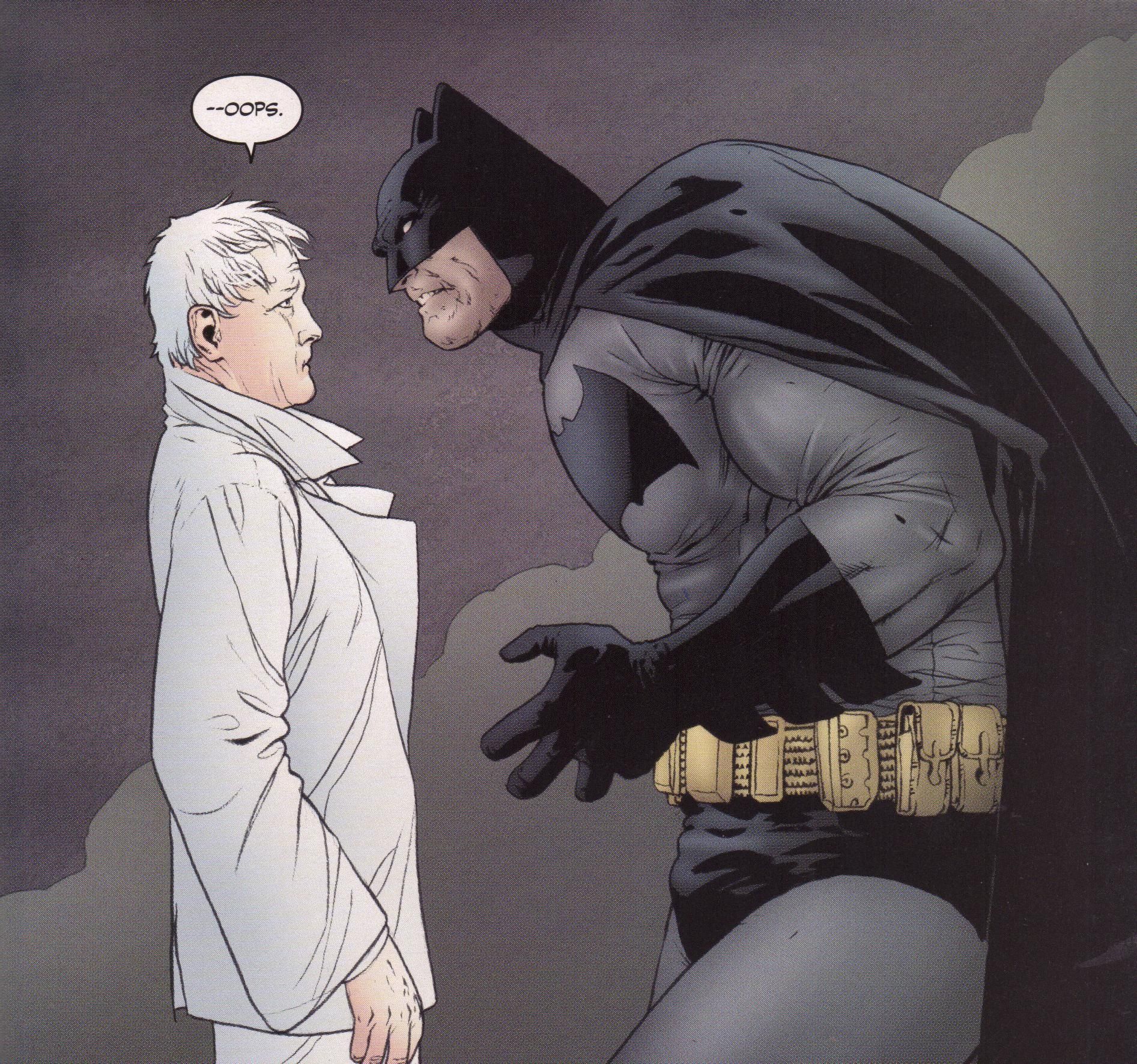

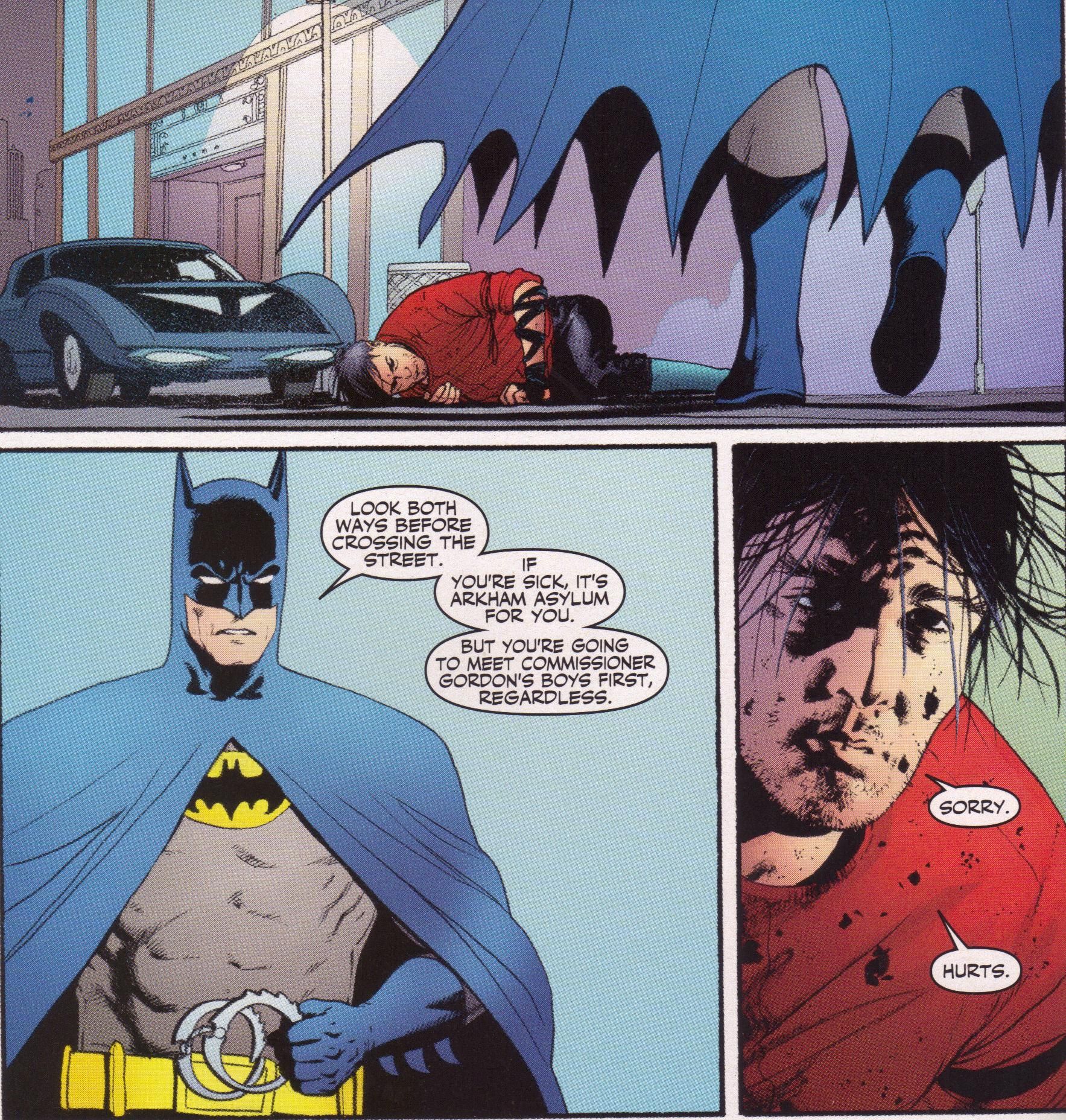

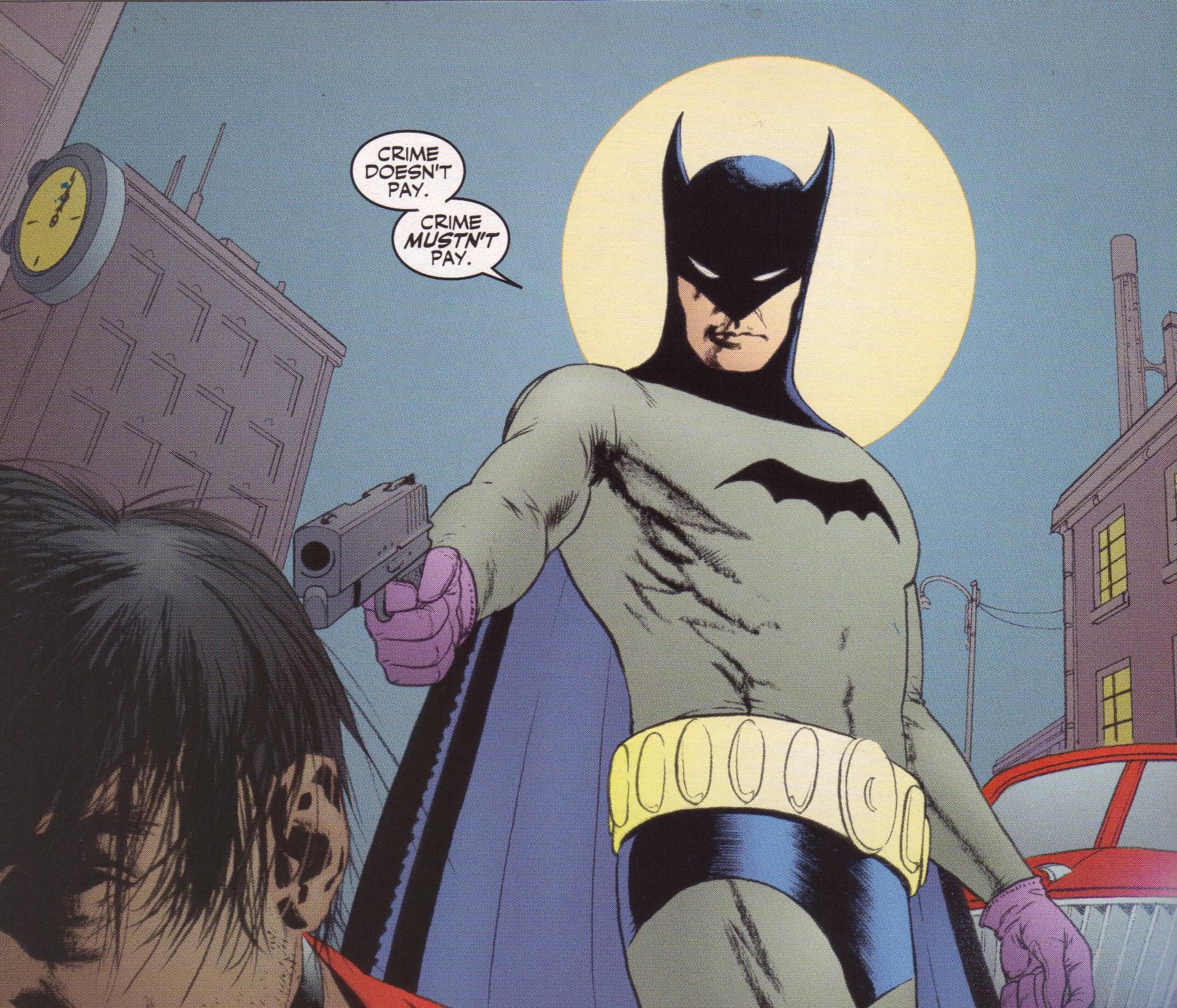

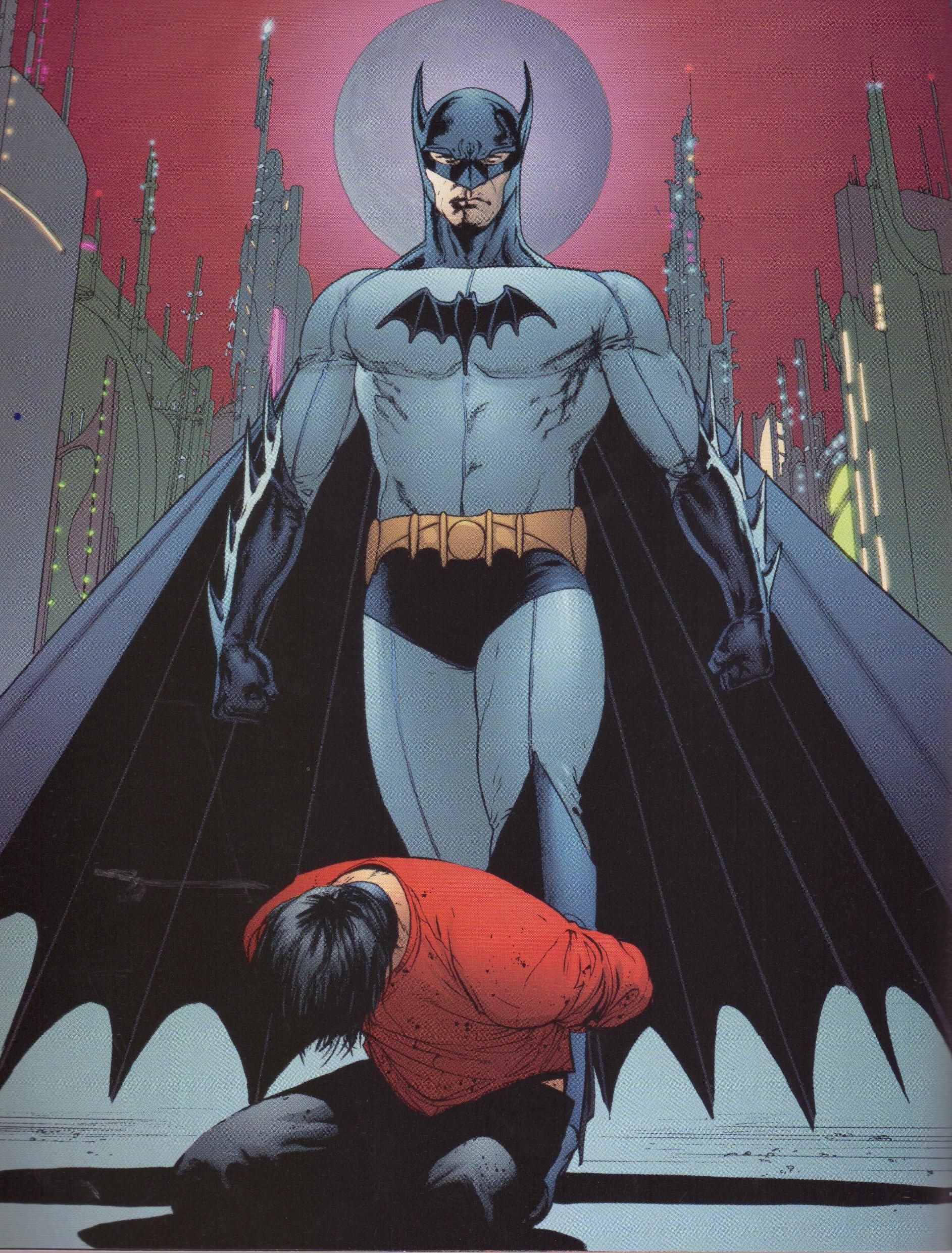

Consider issue #9, "Planet Fiction," which introduces us to Ambrose Chase and his "reality-altering field." The field is a computer effect, causing the linework to ripple around it, but it doesn't look fake or even intrusive - it's just part of the artwork. In issue #3, Cassaday and Martin use the "ghost" effect that was famously introduced (as far as Marvel touted it) in a Joe Mad issue of Uncanny X-Men in the early 1990s (the good old smoke ninja, in case you're trying to remember). It was cool-ass back then but looks fairly shoehorned in these days in that issue of UXM, but in Planetary, it still looks fresh over a decade later. His crowning achievement might be Night on Earth, the Batman crossover from 2003 (during the Great Planetary Caesura!), in which he gives us Batmans from different times in the character's history, from the modern (in 2003) take to the Adam West Bats to the Frank Miller Dark Knight Returns Bats to the Neal Adams version to the 1939 original (complete with purple gloves) to a version that looks eerily like the current David Finch redesign, and he nails every one of them without ever letting us forget it's Cassaday drawing it. Night on Earth is a great story, but it's a beautiful-looking book as well, and Cassaday gets a lot of the credit for that. (Let's not forget the amazing covers for the entire series, with the different logos for each one, because that could be a whole different post if I wanted to get into it.)

Planetary, of course, lost a lot of momentum right in the middle of its run, which was very unfortunate. It was part of the Wildstorm Golden Age (1998-2002; you can see a few of the titles that showed up at that time here) and outlasted all of the others, mainly because it took so long to come out. Between April 1999 (the cover date on issue #1, so it could have come out as early as February) and October 2001, fifteen issues PLUS Ruling the World came out. Then, silence. A year would pass before Terra Occulta came out, but as good as the book is on its own, it might be the one issue of this series that you can skip (it's an Elseworlds tale, after all). Almost a year later Night on Earth came out, and finally, two years after issue #15, issue #16 showed up. The book staggered along through 2004-06, and then issue #27 finally showed up in December 2009 ... three years after issue #26. I have no idea why we got the first delay - Astonishing X-Men first came out in 2004, so maybe Marvel had poached Cassaday as early as 2002 to make sure the book came out on time early in its run (it too experienced delays later on). Ellis famously lost his hard drive in 2007, so that's not it (although it might explain the delay in the final issue). I can't find anything on-line to explain it, but maybe someone remembers. I don't know if the delays have anything to do with a dent in Planetary's reputation, but that would be a shame (especially because you can read it all at once now).

John Layman, the original editor on the series, told me recently that Paul Levitz actually wanted to kill the book around issue #9 or 10, so it apparently didn't have much of a reputation among the DC higher-ups (Levitz, of course, famously dumped The Boys years later, so that would have been quite a track record if he managed to kill this book), but I can't imagine that would have anything to do with the reaction of the fans. All I know is, Planetary is a wonderful series and it deserves a much higher profile than I think it has. If it does have that high profile, well, then, I apologize.

I could write a book about Planetary, but smarter people than I have already done so - it's true! I own that book but haven't read it yet because I didn't want those essays to influence this one, but I'm going to as soon as I post this. I know there's a lot going on in Planetary, but I wanted to write about those few things that struck me when I was re-reading it, and I apologize for not going into even more detail, but that would take me forever. It's available in a few formats, including two Absolute Editions, which I really want because I imagine that Cassaday's art is even nicer in the giant-sized format (the Absolute Editions don't contain the three specials, it appears, which I find surprising - they're collected in a trade, though, so there's that). If you ever jumped ship on Planetary because of the delays, now's the time to get the entire series, sit down, and read it straight through. It's absolutely wonderful, and it will make you wonder if maybe, just maybe, Warren Ellis is the most hopeful writer in comics. When did anyone ever accuse him of that?

There are, of course, archives, if Planetary isn't your thing (for shame!) or if you're looking for other stuff to fill out your collection. Don't be shy!