Handily enough, Marvel has just released the first part of this in trade, so it's easy to pick up! How about that?

Namor, the Sub-Mariner by John Byrne (writer/penciler, issues #1-25; inker, issues #4-21, 24-25; letterer, issues #8-21, 24-25*), Bob Wiacek (inker, issues #1-3, 22-23), Glynis Oliver (colorist, issues #1, 3-19, 21-22, 24), Brad Vancata (colorist, issue #2), Mike Thomas (colorist, issue #20), Joe Rosas (colorist, issue #23), Pat Garrahy (colorist, issue #25), Ken Lopez (letterer, issues #1-7), and Clem Robins (letterer, issue #22-23). * No letterer is credited for issues 8-11, 13, 15-17, 19-20, 21, and 24, but it's fairly obvious that it's Byrne lettering the pages.

Marvel, 25 issues (#1-25), cover dated April 1990 - April 1992.

I suppose there are SPOILERS below (I do spoil the ending, but it's fairly unimportant), but not about the major plot points. As always, click on the images to embiggen them!

John Byrne tends to bring a high level of craft to pretty much every comic book he works on, especially back in his 1980s/early 1990s heyday, so it's no surprise that his run on Namor is so good. There are a few writers who write excellent superhero comics within the framework of a shared universe, and Byrne is certainly one of those - he has a deep and thorough knowledge of what has come before, and he is able to blend that continuity pretty much seamlessly into his grander narrative. He's also not absolutely obsessed with history, as he constantly pushes his characters forward even though he makes sure they remain recognizable in the context of their pasts.

He's also able to embed his stories within the history of the characters without being too obscure, which has bedeviled other writers of his ilk before. In Namor, for instance, he uses quite a bit of Marvel's history to inform the main stories, but his deft touch with writing and Marvel's liberal use of footnotes (a practice that has only intermittently come back into fashion, unfortunately) makes sure that readers who aren't familiar with, say, Warrior Woman (like this reader), can understand perfectly what's going on.

The early 1990s were probably the last time Marvel writers could conceivably reference events that occurred during World War II and not strain credulity with regard to the length of time since the 1940s, and as Namor is linked very specifically to World War II, Byrne is sure to get in a story that links the two time periods. Namor, of course, is one of the many Marvel characters who were at least teenagers during the war but never seem to age (he was born, in fact, in 1920), but Byrne uses other characters who could have been around in the 1940s and could be still alive in the early 1990s to good effect. He doesn't do this too much - the return of the Invaders plot only comes to the fore in issues #10-12 - but because Namor has such a long history, Byrne is able to use it quite a bit, and without using the vague time frames that later writers were forced to use. When he wants to show why Warrior Woman was left in suspended animation while Master Man remained awake, he can reference the building of the Berlin Wall without too many problems.

The return of Master Man and Warrior Woman give Byrne an opportunity to allow the characters to discuss the reunification of Germany in the early 1990s, which seems benign these days but did trouble many people, especially those who had been alive during Hitler's rise to power. Byrne uses Namor, among others, to voice these concerns, and it adds a nice touch of "realism" to the plot of evil Nazis reviving from suspended animation.

The far larger plot of Byrne's Namor is, strangely enough, the resurrection of Danny Rand. Byrne, of course, had worked on Power Man and Iron Fist in the 1970s, and by the time that series had run its course with issue #125 (1986), Danny Rand had changed quite a bit and, of course, was killed off. Byrne decided to bring him back, and the second half of the Namor run (issues #13-25, although Byrne seeded it even before that) deals quite a bit with Namor's quest to find Danny Rand, with Misty Knight and Colleen Wing riding shotgun. Why Byrne felt the need to do this in a comic starring the Sub-Mariner isn't clear, but that's not the point. The point is that Byrne, with his encyclopedic knowledge of Marvel history, performs a retcon that works by using events that have already been printed and turning them to his advantage - in this case, the final six or so issues of Danny and Luke's series, which he interprets to fit his agenda. Byrne had done this before - most famously with Jean Grey - but he's good at it, so it's interesting to watch the machinations. Plus, unlike many writers these days, he doesn't invent things and slip them into breaks between issues or even between pages, so that Danny's resurrection feels far more natural than, say, Gwen Stacy banging Norman Osborn. Byrne is clever enough to use the vast tapestry of Marvel comics to create new stories and rescue characters from oblivion, rather than simply using the character and making up the justification as he goes along.

It's an important distinction, because it's a reason that Marvel comics of the 1970s, 1980s, and even into the 1990s, while they varied in quality, "felt" more "important" - the writers were less interested in glorifying themselves and more interested in writing a good story that fit into the grand narrative of Marvel history.

Now I need to get off my soapbox and discuss some of the other nuts and bolts of the run. Byrne begins by having Namor snag some buried treasure (a ploy he used long ago in Fantastic Four) and buy a company. Yes, it's the Adventures of Namor, CEO! The idea of a superhero/businessman isn't new, of course, but most of the tycoons of the Marvel and DC universes were born into wealth, so the idea of Namor taking over a small company, renaming it (to Oracle, Inc.), and making waves in the world of high finance is intriguing. Byrne doesn't get as much out of it as he might have, but he does give us Phoebe and Desmond Marrs, twin empire builders who vex Namor for a great deal of the run. The Marrs siblings are bombastic and somewhat silly villains, prone to grand, even Byronic gestures like suicide (we first see Desmond holding a gun to his head, bored because he's conquered everything, and he only gets his mojo back when he realizes his new foe is Namor), but they provide interesting foils for Namor - Desmond is his opposite in terms of business dealings, while Phoebe contends with Carrie Alexander as Namor's love interest. Early on in the run, Byrne actually seems interested in having Namor deal with "real-world" issues - in a comic-book way, of course, but still - as in issues #4-5, when he has to clean up an oil spill in New York harbor, and even in issues #6-7, when he must fight a genetic mutation gone horribly wrong. Byrne can't keep the superheroics out of his treatment of Namor's business, however, and in issues #8-9, he has to fight the Headhunter, who has made deals with various businessmen over the years that keep their businesses afloat for a time ... until she arrives for payment, which is mounting their heads on a wall and stealing their financial advice. It's a silly idea, made even sillier by the fact that the Headhunter doesn't actually decapitate her victims, just makes it appear she does (like almost all other comics of this era, it's a kid-friendly book). Even during the Danny Rand epic, Byrne makes interesting points about the exploitation of the Savage Land and continues to check in with the Marrs twins - he was writing Iron Man at the time, so Desmond Marrs tries to take over Tony Stark's company, and when he failed miserably, it had dire consequences for him back in Namor.

While the business aspects of Byrne's Namor are never fully developed, it's an interesting way to get Namor back into the Marvel universe and allows Byrne to bring in some environmental ideology without being too obnoxious about it.

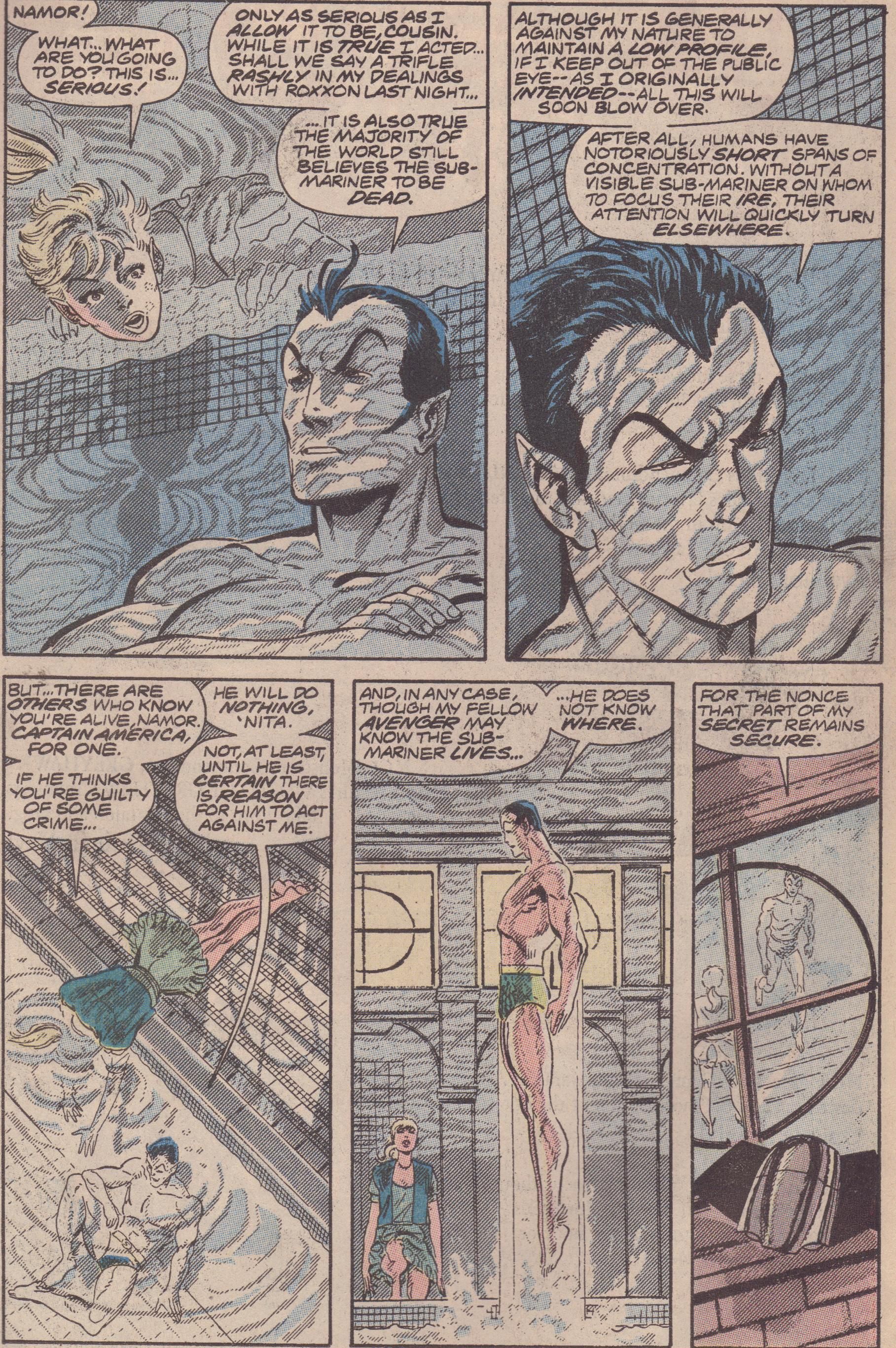

Another reason these are books to own is the artistic choices Byrne makes throughout the series. Whether or not you like Byrne's clear, precise, almost old-fashioned line work will go a long way toward whether or not you like Byrne's comics, because while his art is not flashy, it does have a distinctive style. Issues #1-3 of this series are inked by Bob Wiacek, another old-school artist who embellishes like we'd expect - a bit of definition of the muscles, not a lot of soft shading, very black-and-white. Then, in issue #4, the art style changes. Byrne begins to ink himself, but what makes the art so interesting is that he begins to use Duo-Shade (as Terry Kavanaugh explained in the letters page of issue #7, contrasting it with Zip-A-Tone, which one letter hack thought he was using). Duo-Shade, for those who don't know, is a pattern printed onto the Bristol board. An artist could pencil and ink onto the board, then treat the board with a chemical that would reveal shading lines or dots (as opposed to Zip-A-Tone, which is a plastic film laid over the finished artwork). What this does is allow Byrne to shade in a much softer tone, giving him freedom to add more subtle shading to muscles and facial expressions while also turning the water scenes in the comic (which are, after all, kind of important) into things of beauty. He can turn a simple scene of Namor in the pool into a wonderful contrast between the air and the water (from issue #4, page 7):

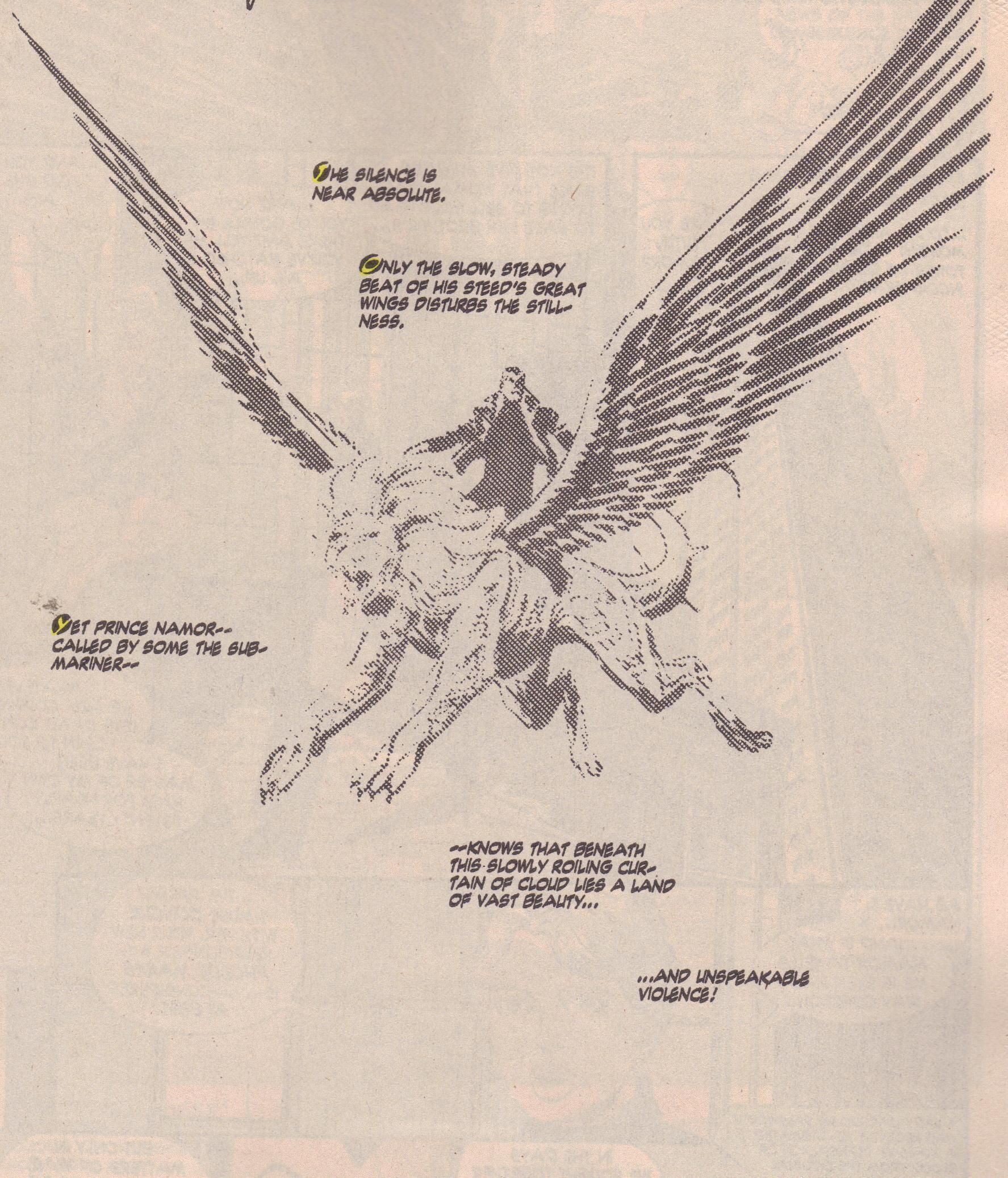

The Duo-Shade takes some getting used to, as it blurs Byrne's powerful lines a bit. But Byrne's use of it, along with Glynis Oliver more muted palette (I don't know if she deliberately changed her style when Byrne started using the Duo-Shade or if the paper itself mutes the colors), turns Namor from a typically well-drawn Byrne comic into a far more subtle and interesting work of art. The shading itself seems to move the book into a more morally compromised universe, as well as making things like Sluj (the genetic monster from issues #6 and 7) more of a slimy muck than it would be otherwise. The Headhunter, who had shown up in the earlier, Wiacek-inked issues, becomes a more malevolent force thanks to the softening of her edges - it's very interesting to contrast her at the end of issue #8, when she lures Namor and Phoebe Marrs into her red-tinted lair, and issue #9, in which Byrne does not appear to use the Duo-Shade, as she looks far creepier in the former issue rather than the latter. Duo-Shade was a long-time favorite of editorial cartoonists (it's not made anymore), and Byrne shows that in issue #10, when Namor reads the newspaper and a cartoon reflects the fears people felt about German reunification. Meanwhile, Oliver's coloring continues to evolve throughout the course of the book, as she is able to spruce up some of the primary colors more (the original Human Torch's fiery red costume, for instance) while still keeping the rest of the book somewhat muted. It makes the book feel more "realistic" - the spandex of the original Human Torch or Union Jack constrasts well with the regular clothes most of the cast wears. Of course regular fabric would look duller in comparison to the brightly-clad heroes, and Byrne's technique helps in that regard by adding more "folds" to the regular fabric while keeping the costumes wrinkle-free. The Duo-Shade also allows Byrne to cast Namor in fog in issue #15 simply by revealing the lines on the board without, it appears, even inking his very light pencils. Just the patterns on the board is enough to make Namor's ride on the Griffin look truly as if he's flying through thick clouds:

Byrne seems to have abandoned the Duo-Shade after issue #17 (he obviously didn't use it on issues #9 and 16, for no clear reason), and while the artwork remains as sturdy as ever, it's a shame that he didn't stick with it. The editors don't give any reason for it, either. According to some sources, it's faster than "normal" drawing, but I don't know if that's true. Late in the run, Byrne was obviously pressed for time - he needed Wiacek back on inks, and issue #22, for instance, looks very heavily finished by Wiacek, to the point that a few panels don't look like Byrne at all. Perhaps Byrne very much wanted to write and draw his entire epic, but 25 consecutive issues was pushing him hard. Either way, while the other issues are well drawn, issues #4-8, 10-15, and 17 are the artistic highlights of the run. Byrne has done art like this in other places (OMAC most notably, as well as on one issue of She-Hulk), but according to him, with improvements in comics coloring, it became unnecessary. That's an opinion I don't share.

For the most part, Namor is a grand adventure that is firmly set within a shared universe, and Byrne has a lot of fun with it.

He gives a new lease on life not only to Danny Rand, but to Spitfire and the original Human Torch as well, all done with aplomb and an eye toward the history of the Marvel Universe and the "comic-book science" that operates within it. Namor may seem like a standard superhero book, but a few thing elevate it: Byrne's marvelous work with established history, the twist of having Namor more involved with business, and the experiments with the art. These innovations make Namor far more memorable than a run-of-the-mill superhero book. As with so many of Byrne's work, the story doesn't end with issue #25, even though Byrne wraps up many loose ends. In saving Danny Rand from the H'ylthri - the plant people of K'un-L'un - Namor incurs the wrath of Master Khan, who wipes Namor's memory and teleports him away at the end of issue #25. Byrne continued to write the book for a time, and Namor does manage to defeat Master Khan, but not until issue #33. So why aren't those Comics You Should Own?

Well, they're not all that good, unfortunately. Byrne begins with a bang, continuing the environmental theme he had explored when Namor ran Oracle, Inc., as he put the "savage" Namor in the Pacific Northwest and threw him into a showdown between environmental terrorists and loggers. But, like with many of his projects, Byrne seemed to lose interest in that and the overall title quickly, and he even left the book after issue #32, leaving Bob Harras to script the big finale. This brief story is notable only for the artwork of Jae Lee, getting his big break at the age of 19 after some work on Marvel Comics Presents.

Lee's art, while very much of the Image school of the early 1990s, shows a huge amount of skill and energy, and it makes the meandering story read better than it ought to. But it's not enough to make them worth your while. Although issue #25 ends on a cliffhanger, most of what Byrne wanted to say he had already done so. The follow-ups are okay if you can find them cheap, but nothing really to dig for.

Marvel, unlike DC, appears committed to collecting some of their 1980s/1990s work in trade paperback, and as I noted at the beginning of this post, the first nine issues have recently been collected in a "Visionaries" trade. (The next one, if offered, will probably be issues #10-18, and the last will be issues #19-25, unless Marvel gives up on them.) They do, however, read very well in single issues, because Byrne, like other writers from that era, was very good at writing single issues, even as he was seeding the pages with scenes that didn't pay off until much, much later in the run. We get cliffhangers in almost every issue, which makes it an odd experience to read in one sitting but makes it stronger when you have to wait a month between installments. I deliberately left out a lot of the plot developments of Byrne's story because I hate to ruin it for you and because it is fun to see how everything fits together when Byrne gets around to explaining it all, but trust me - this is a heavily-plotted series that, like the best comics of this era, managed to pack plenty onto each page. I'm not sure how hard the single issues are to find, but with Marvel reprinting the first part, perhaps it's best to wait until the rest is released in trade. It's entirely up to you!

Be sure to examine the archives of these posts. You never know what you might find!