This couldn't have anything to do with a certain B. Sienkiewicz, could it?

Moon Knight by Doug Moench (writer, The Hulk! magazine #11-15, 17-18, 20; Marvel Preview #21; issues #1-15, 17-20, 22-26, 28-33), Jack C. Harris (writer, issue #16), Tony Isabella (writer, issue #34-35), Alan Zelenetz (writer, issues #37-38), Bill Sienkiewicz (artist, The Hulk! magazine #13-15, 17-18, 20; Marvel Preview #21; issues #1-15, 17-20, 22-26, 28-30),

Gene Colan (penciler, The Hulk! magazine #11), Keith Pollard (penciler, The Hulk! magazine #12), Denys Cowan (penciler, issue #16), Kevin Nowlan (penciler, issues #31-33, 35), Bo Hampton (artist, issues #34, 37-38), Tony DeZuniga (inker, The Hulk! magazine #11), Frank Giacoia (inker, The Hulk! magazine #12; issue #8), Mike Esposito (inker, The Hulk! magazine #12), Josef Rubinstein (inker, The Hulk! magazine #13; issue #16), Bob McLeod (inker, The Hulk! magazine #14-15; artist, issue #35), Klaus Janson (inker, The Hulk! magazine #17-18; issues #3-7, 16), Tom Palmer (inker, Marvel Preview #21), Dan Green (inker, Marvel Preview #21), Frank Springer (inker, issues #1-2), Steve Mitchell (inker, issues #16-20), Terry Austin (inker, issue #31), Carl Potts (inker, issues #32-33, 35), Brent Anderson (inker, issue #33), Joe Chiodo (inker, issue #33, 35), Armando Gil (inker, issues #37-38), Bob Sharen (colorist, issues #1, 3-5, 9-10), Carl Gafford (colorist, issues #2, 6), Don Warfield (colorist, issue #7), Roger Slifer (colorist, issue #8), Christie Scheele (colorist, issues #11-20, 22-26, 28-35, 37-38), Tom Orzechowski (letterer, issue #1), Annette Kawecki (letterer, issue #2), Joe Rosen (letterer, issues #3, 7-10, 12-13, 15, 23-26, 28-33, 35, 37-38), Rick Parker (letterer, issues #4-6, 11, 30-34), Janice Chiang (letterer, issues #11, 14, 16-18), John Morelli (letterer, issues #19-20), and Mike Higgins (letterer, issues #22, 30, 35). Back-up stories: Harris (writer, issue #16), Moench (writer, issue #17), Zelenetz (writer, issue #22, 32), Denny O'Neil (writer, issue #26), Steven Grant (writer, issue #29), Steve Ringgenberg (writer, issue #31), Jimmy James (penciler, issue #16), Cowan (penciler, issue #17), Greg LaRocque (penciler, issue #22), Pollard (artist, issue #26), Nowlan (artist, issue #29), Mike Hernandez (penciler, issue #31), Marc Silvestri (penciler, issue #32), Gil (inker, issue #16), Rubinstein (inker, issue #17), Joe Albelo (inker, issue #22), Kevin Dzuban (inker, issue #31), Gary Kwapisz (inker, issue #32), Scheele (colorist, issues #16-17, 22, 26, 29, 32), Sharen (colorist, issue #31), Parker (letterer, issue #16, 22), Chiang (letterer, issue #17, 26, 29), Rosen (letterer, issue #31), and Morelli (letterer, issue #32).

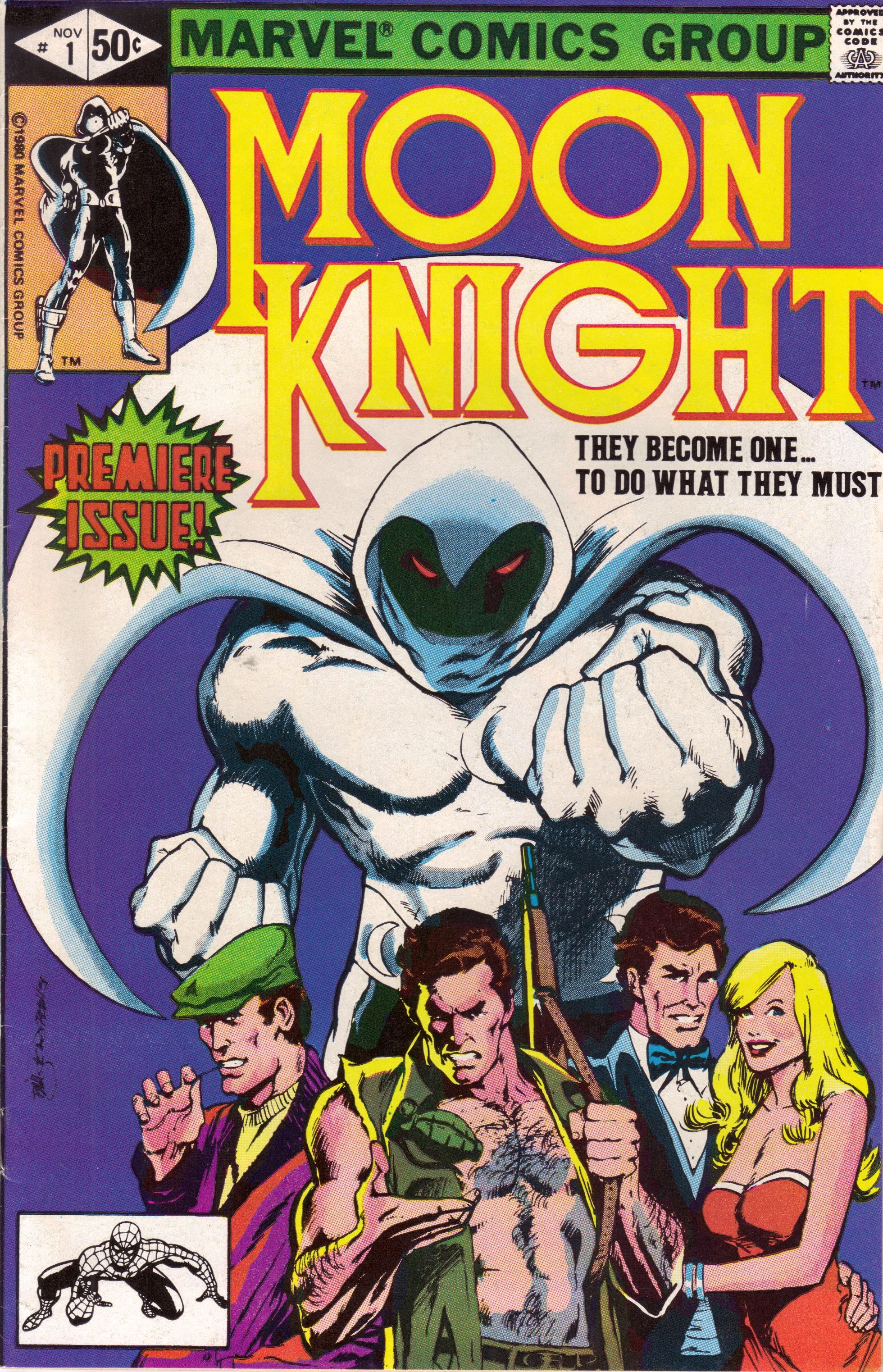

Marvel, 44 issues (The Hulk! magazine, issues #11-15, 17-18, 20; Marvel Preview #21; issues #1-20, 22-26, 28-35, 37-38 of the ongoing series), cover dated October 1978 - April 1980 (The Hulk! magazine and Marvel Preview #21) and November 1980 - July 1984 (ongoing series).

Some big SPOILERS below, but these are 30-year-old comics, so perhaps "spoilers" is a relative term. For the most part, I try to keep the spoilers to one issue, but in that case, it's pretty important. So read at your own risk!

"Sluts." On the fifteenth page of the Moon Knight story in The Hulk! magazine #11, "Graven Image of Death," Fenton Crane, a man involved in a complicated plot with a Horus statuette at its center, calls Marlene, Moon Knight's lover, a "slut." This issue, cover dated October 1978, written by Doug Moench and drawn by the incomparable Gene Colan, signals a shift in mainsteam superhero comics, and the word "slut" is at its heart. At this point, the appearances of Moon Knight in the Marvel Universe were rather bland and forgettable - he first appeared as a "villain" in Werewolf by Night #32-33 in 1975, hired by a group called The Committee to bring in Jack Russell so they can use him to kill people - and then showed up in various places over the next few years (including briefly hanging out with the Defenders for a few issues) before Marvel decided to put him in the back of The Hulk! as a counter to the main character's big, bombastic stories. Moench, who co-created the character (with Don Perlin) came back on board, and immediately began taking Moon Knight in a much darker direction than previously. Crane calling Marlene a "slut" is central to this direction. The Hulk! shipped without a Comics Code Authority stamp because it was a magazine, so it gave Moench a bit more freedom to use more "adult" language and some darker themes.

The first storyline, which ran through issues #11-14, evolves slowly from a scheme with the Horus statuette to nuclear blackmail and is a fairly standard action thriller, done very well, to be sure, but nothing revolutionary. With "Nights Born Ten Years Gone," which ran in issues #17 and 18 of the magazine, Moench explored a much darker story, featuring a serial killer with a very personal connection to Marc Spector, Moon Knight's alter ego (well, one of them). In many ways, this is another standard plot, but Moench was unafraid to take it to a horrific conclusion and put characters we think are untouchable in harm's way. In Marvel Preview #21 (which also shipped without a CCA stamp), Moench goes to what would become a favorite well for him, mind-control experiments by the CIA, and while it's another action thriller, the subtext of the government ruining people for their own gain is a sufficiently dark theme. These stories set the stage for the ongoing, which, for a time, did ship with a CCA stamp but had the background of more mature storytelling, and Moench and his artistic collaborator, Bill Sienkiewicz, took advantage of this leeway.

Marvel did a lot of experimentation with Moon Knight, perhaps in a bit of synergy with the Moench/Sienkiewicz experimentation. While Moench decided to heighten the strangeness of secret identities by giving Moon Knight four separate identities (the superhero one; Steven Grant, the millionaire; Jake Lockley, a taxi driver; Marc Spector, the soldier-of-fortune who's the original personality - and it should be noted that Moench first came up with the identities in Marvel Spotlight #28, which came out in 1976, long before the ongoing premiered) and Sienkiewicz gradually changed from a Neal Adams clone to a Frank Miller clone to a genius artist in his own right, Marvel toyed with the way they presented the series. It shipped with the CCA code for the first 15 issues, which were generally well within the confines of what was "acceptable" in mainstream comics at that time, even though Moench continued with the darker stories.

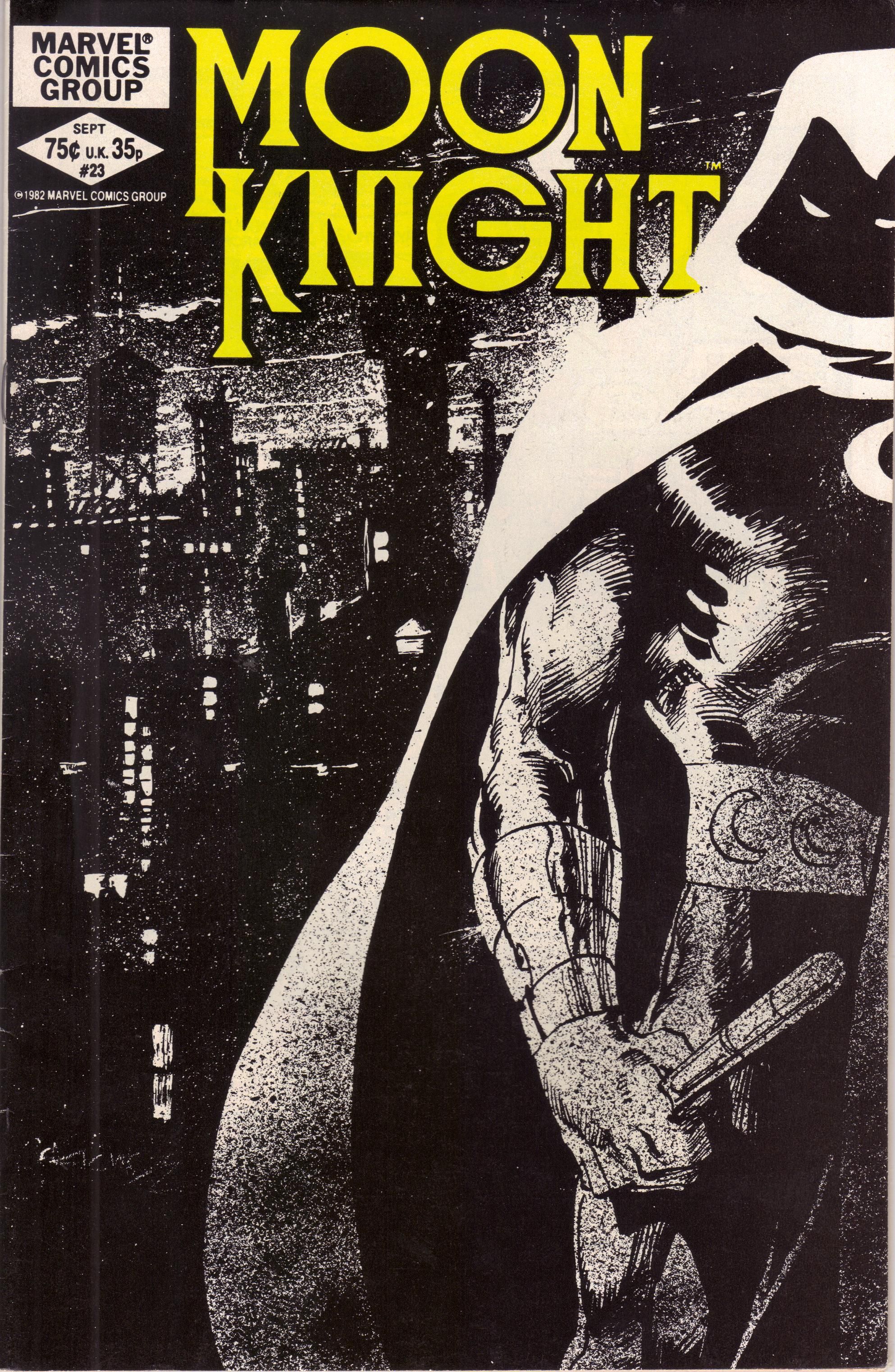

In issue #15, which was approved by the Comics Code Authority, Marvel changed the format of the series. They increased the price from fifty cents to seventy-five and increased the story pages from 22 (in issue #14) to 27 (in issue #15; the stories varied in length from then on, with occasional back-up stories filling in the page count). Moreover, they completely eliminated interior advertising. I'll write that again: They completed eliminated interior advertising. Finally, with issue #16 they shipped it without the CCA stamp. Also, beginning in issue #15, Moon Knight - along with Micronauts and Ka-Zar the Savage - was sold only through subscription and in comics shops, and no longer on newstands. Marvel did this in late 1981, and it was a major shift in the way comics were sold and heralded the onset of the direct market that is still with us today. Marvel believed this meant the comics could go out without internal advertising and without the Comics Code, and for the rest of its run, Moon Knight was published this way. It didn't work perfectly, of course - the book did get cancelled, after all, and beginning with issue #32, it was forced to go bi-monthly - but it did manage to last for almost three years before it got the axe. And, of course, publishing it without the CCA approval meant that Moench and Sienkiewicz were freed even more to do boundary-pushing stories, and as Sienkiewicz was just starting to come into his own when Marvel went this route, it was a perfect marriage of corporate envelope-pushing and creative envelope-pushing. One of the more impressive things about the way Marvel published Moon Knight is that, through the letters page and Denny O'Neil's editorials later in the run, they kept the readers apprised of the changes and why they were doing it. Moon Knight, no matter what anyone thinks of its quality, remains a highly influential comic both in terms of storytelling and art and the way the companies produce comics, for better or for worse.

Of course, none of this makes Moon Knight a Comic You Should Own. It's just interesting how much Marvel tried to change or at least follow the trends of the comics culture and used Moon Knight to do it, making it a very influential but unrecognized series.

Perhaps Marvel's decision to put the book in the back of a magazine, meaning Moench could explore darker themes without fear of censorship, helped when, early in the ongoing, the series was "code-approved" but was still more cutting-edge than what was normal for mainstream comics 30 years ago. It's not Sienkiewicz, necessarily - as issues #11 and 12 of The Hulk! show, Moench was doing this kind of thing when Colan and Pollard were drawing it, and while Colan had a very modern sensibility, Pollard, while a good draughtsman, is very bound by his time and his art looks horribly dated today, and bookended by Colan and Sienkiewicz, it looks even worse. Early on in the ongoing, Moench pulled back a bit on the dark themes and the stories suffered a bit. The Hulk! #17 and 18 gave us Randall Spector, Moon Knight's brother, whose rivalry with his brother Marc drove him to madness and murder, destroying one of Marc's loves and severely wounding another. It's an intensely personal story, getting to the heart of who Marc Spector once was, who he is now, and what haunts him. Moench doesn't pull back completely from this early in the ongoing, but he does strike a balance between more personal stories (issues #1, 2, 9-10, 12, 14) with more action/adventure stories. After Marvel began shipping it without the CCA stamp, the first story was a four-parter (#17-20) that was a very James Bondian adventure (and, in marked contrast to today's decompressed stories, the only time any of the stories ran longer than two issues), but issues #22-26 and 28-30, the high point of the series, were stories that dealt with Marc Spector personally and the way he interacted with the world. It's no coincidence that these issues show Sienkiewicz at his absolute best, which allowed Moench to stretch his creative wings as well.

Several writing elements make Moon Knight impressive, and one of them is not necessarily Moench's way with words. While he's a good plotter and writes decent dialogue, Moench has never been accused of being an innovator, and therefore he's firmly within the then-current tradition of using lots of narrative captions (with a heavy-handed omniscient narrator) and thought balloons.

These are verbose comics, often to their detriment, as even before he became wildly experimental, Sienkiewicz was a fine storyteller, and Moench's prose occasionally threatens to overwhelm the visual aspects of the comic. But Moench makes up for it with very good plots, very good characterization, and the aforementioned solid dialogue. He came up with the major plot points of Moon Knight's life - the first one, of course, is the creation of four different identities for his hero. This is a brilliant bit of satirical prodding at superheroes' secret identities - if most heroes have two identities - their "heroic" one and their "civilian" one - why not give Marc Spector two more? Moon Knight, the hero, is the pure one, of course. Marc Spector becomes both the skeleton in the closet and a plot contributor - several stories feature people from Marc's past who need his help. Marlene, for one, is scared of Spector, because he's the hard mercenary who got her father killed and who ends up at her mercy in the tomb of Seti where the statue of Khonshu "resurrects" him. (In a hilariously sexist sequence in issue #1, Marlene finds him dead on the floor and, after exulting that one of her father's killers has paid the price, monologues: "What's wrong with me? How can I be glad that a man is dead? He did save me! That might have been what cost him his life! He must have suffered horribly in the desert! He was ... handsome!" That Marlene - always keeping what's most important in mind!) Spector's plunder and stock market savvy buys his way into New York high society as Steven Grant, Marlene's favorite identity. Jake Lockley, the cabbie who works the streets picking up information about bad guys and who recruits a group of agents, Shadow-style, is necessary because the lower classes trust him. Crawley, the homeless man with whom Jake forms a bond, and Gena, the owner of the diner where Jake hangs out (not to mention Ricky and Ray, Gena's kids), trust Jake more than Steven even after Jake brings them into the "circle of trust" that includes Marlene and Frenchie, his helicopter pilot (who eventually gets a name - Jean-Paul - but who only gets one story that fleshes out his character very much). Moench does more with the parodic aspects of the identities than the serious issues of a man with possible multiple personalities - Samuels, the put-upon butler, is never certain to whom he's speaking, and Marlene often gets frustrated by the switches, while Frenchie, who has known Spector for years, simply ignores his friend's eccentricities and always calls him "Marc" - but in issue #22, Peter Alraune, Marlene's brother, who has unwittingly become a pawn of the villain Morpheus, is able to send Moon Knight into a dream-world where his alter egos confront him.

As the series moved on, Moench shows how desperately Spector wants to escape from his past, but he simply can't.

Moench reworks his origin in issue #1, showing that he was Moon Knight long before Werewolf by Night #32 (a discrepancy that is explained away in issue #4). Spector was a soldier with a mercenary named Raoul Bushman, who is far more crazed than Spector likes. While fighting in the Sudan, Spector stops Marlene's father, a famed archaeologist, from killing Bushman, and in turn, Bushman brutally murders the man. Later, however, Spector facilitates Marlene's escape, and when Bushman guns down innocent civilians, Spector tries to kill him. Instead, Bushman leaves him for dead in the desert, but he reaches the tomb of Seti, where he "dies" and then comes back to life. Believing Khonshu, the Egyptian god of the moon, resurrected him, Spector becomes his earthly avatar. But now that he has become a "hero," he tries to escape from Spector, and Moench gets some of his best stories out Spector's past coming back to haunt him. In fact, the past haunting the present is a huge part of the book, not only when it comes to Spector. Moench began this trend, of course, when Randall Spector re-appeared. In "Mind Thieves" (the story in Marvel Preview #21), Marc must confront people from his time with the CIA. In issue #2, Crawley must confront his past mistakes, sins that have created a madman. "Ghost Story" from issue #5 tells a story of a felon who desperately needs to find something in his childhood house. His partners think it's treasure, but it's something a bit more mundane ... and more twisted, as it turns out. In issues #9 and 10, Bushman returns, and his ally, the Midnight Man (who first appeared in issue #3), destroys the statue of Khonshu that Spector brought back from the desert. Spector believes this gives him power, so even though he escapes from Bushman, he cracks under the strain of losing the statue.

This is the first time Moench hints that Marc might be seriously ill, but Marlene reveals the "real" statue - she claims she displayed a replica just in case someone tried to steal it - and Moon Knight comes back stronger than ever, defeating Bushman easily. In issue #11, the past comes back to haunt Frenchie, as an old flame shows up with a mysterious package and gets them involved in a tale of intrigue. (Isabelle dies in the issue, so she and Jean-Paul don't get back together, but it's interesting to re-read this issue - and others where Jean-Paul's romantic life is referenced - with the knowledge that he's now out of the closet. Moench, of course, was not writing him as a gay man, so it's not as if anything is veiled, but it's fun to figure out what his exact relationship with Isabelle - and other women - really was.) Just before Marvel stopped shipping it with CCA approval, Moench gave us the first story of Morpheus in issue #12, which involved Marlene's brother, and the first story of Scarlet Fasinera in issue #14. Scarlet married a mobster and her son became a murdering felon, and she takes it upon herself to hunt him down. It's another example of the past coloring the present and how difficult it is to escape your mistakes. For a comic with an advertisement for Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends on the cover, it's a remarkably mature story.

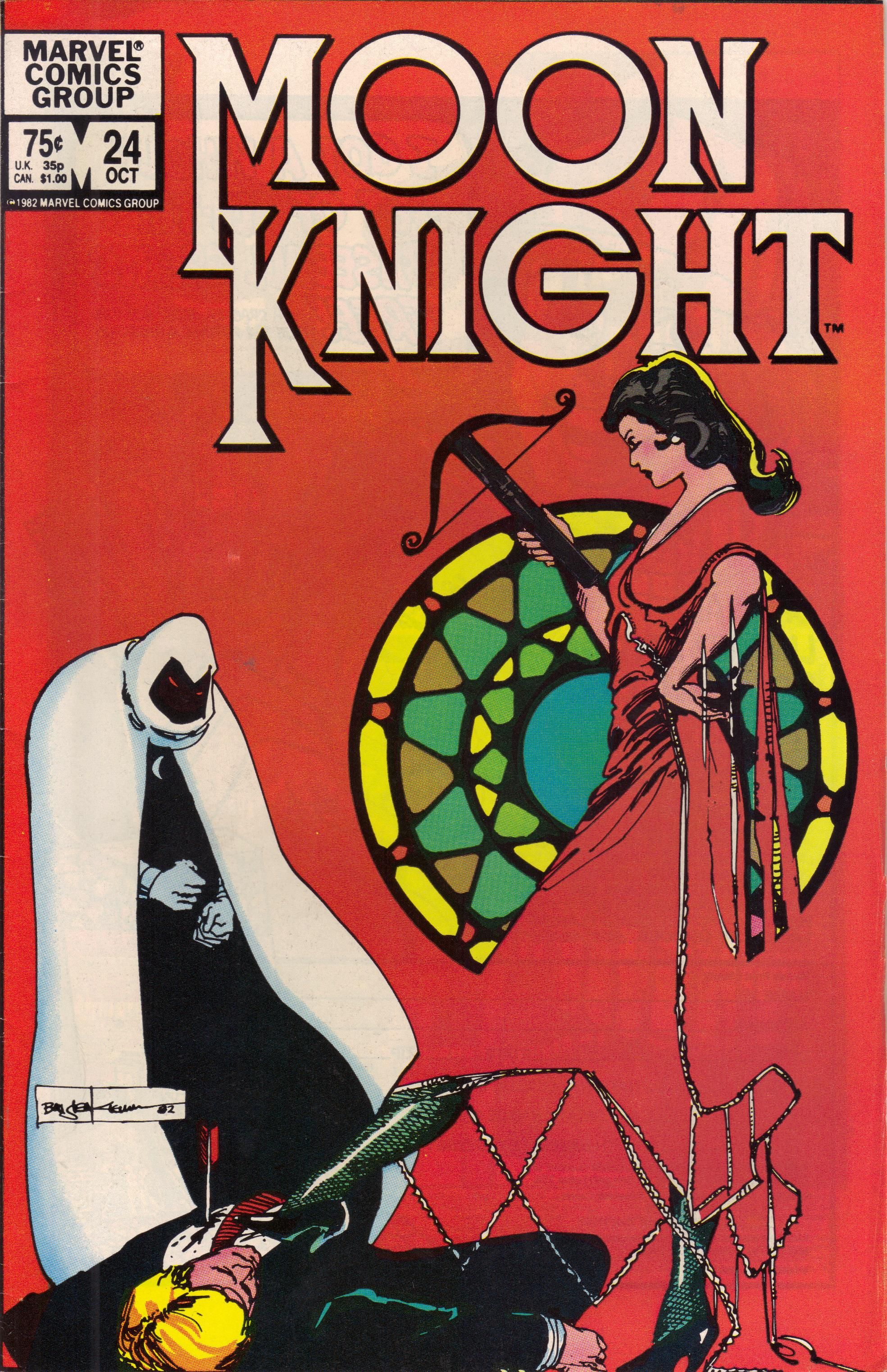

With the change in format, Moench continued to open up his storytelling. I wrote above that issues #17-20 were a grand action/adventure story, but it still began with a man from Marc's past showing up with a problem. Even as the story zips all over the world and features bikini-clad babes and explosions and tough guys fighting, it ends with Marc's friend's widow, weeping over her dead husband. Moench never forgets the characters and the pain they go through. It's in issue #22, coinciding with Sienkiewicz's growth as an artist, that Moench really blossoms. We get the confrontation with his past selves in issue #22, and Marlene's brother sacrifices himself to stop Morpheus in issue #23. Issue #24 brings the return of Scarlet Fasinera, who has declared war on the criminals who made her son into a murderer. Moon Knight claims to abhor murder, but he's torn by his desire to see justice done and that hatred of murderers. This is, of course, a common theme among superheroes who don't kill - I doubt if we can count the number of times a superhero has to decide between letting someone like Scarlet kill mobsters or stopping her - but Moench does a good job with it, and of course he has Sienkiewicz drawing it.

The double-sized issue #25 gives us Carson Knowles, a Vietnam vet who, after years of rejection by his wife, his country, and by potential employers, decides to become a villain - Black Spectre - who is Moon Knight's antithesis, and also to run for mayor so he can destroy New York from the inside. Moon Knight discovers early on that Carson Knowles is Black Spectre, but nobody believes him, least of all Marlene, who leaves Marc to work for Knowles's mayoral campaign. Frenchie is beaten by Black Spectre's goons, the cops think Moon Knight is losing his marbles, and Marlene is gone - for the second time in the series, Marc is as low as he can go, but he manages to get it all back. The story resolves itself a bit too quickly, but it's an interesting take on the down-and-out hero - unlike issue #10, Marc doesn't have anyone to help him back up, and he needs to do it by himself.

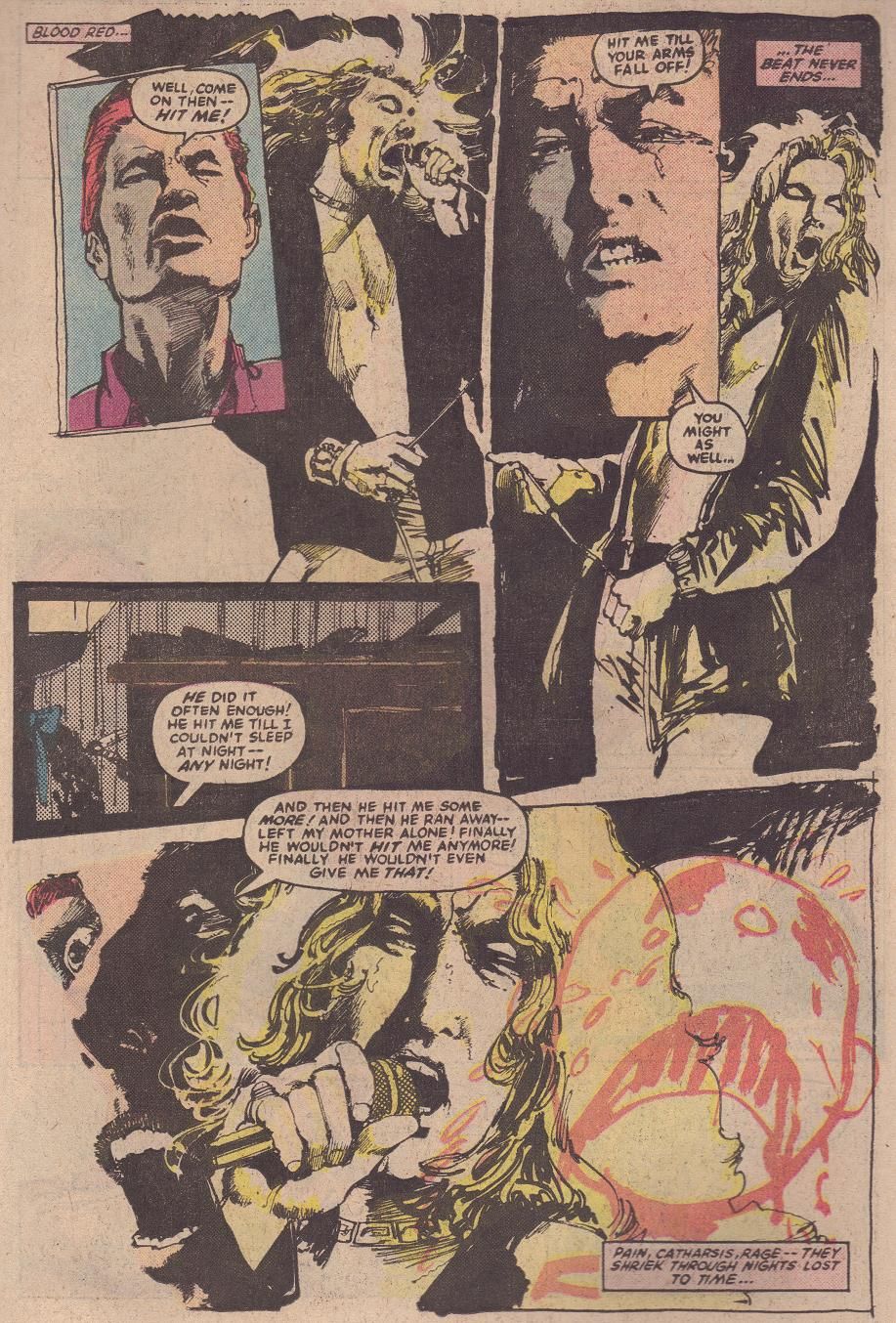

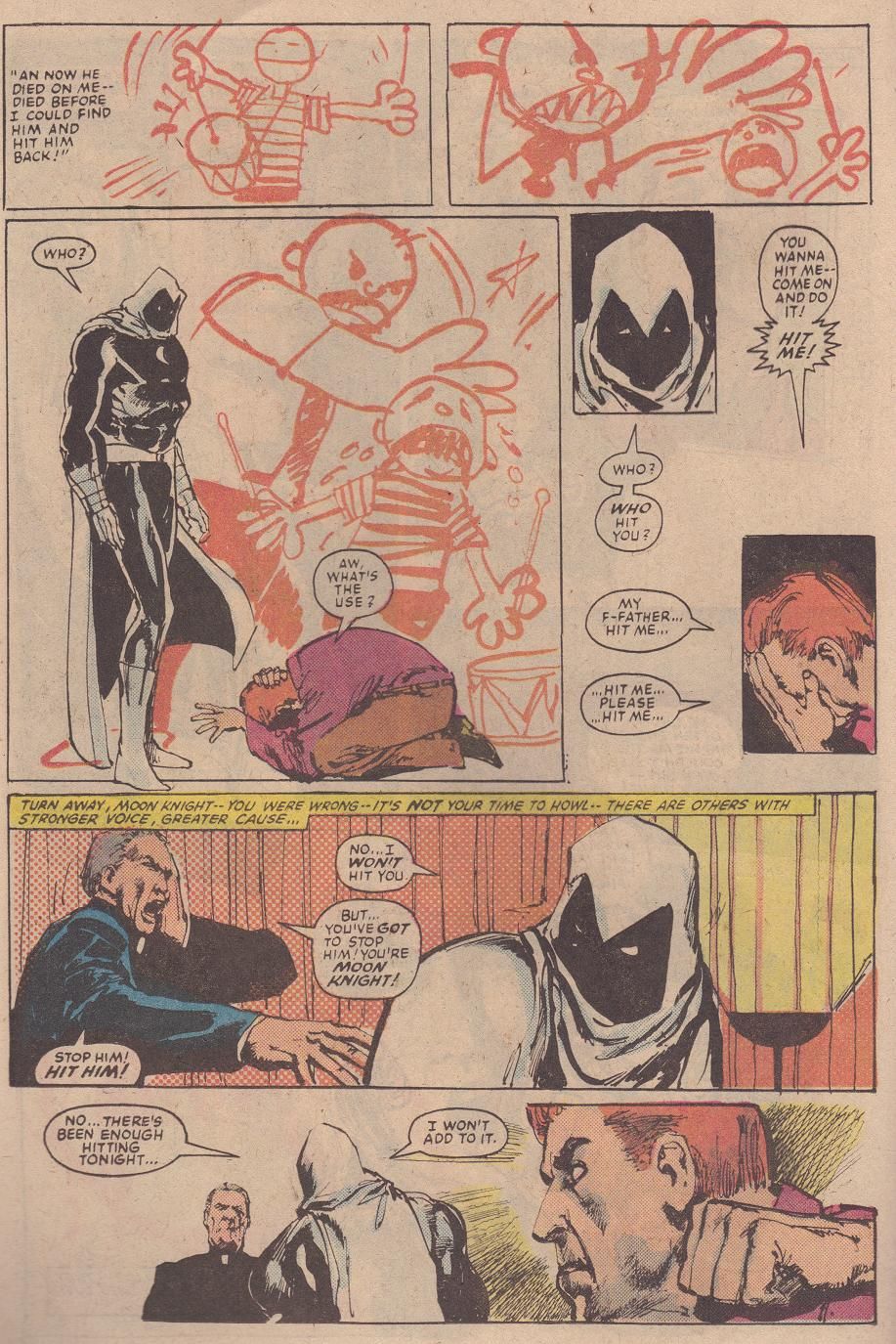

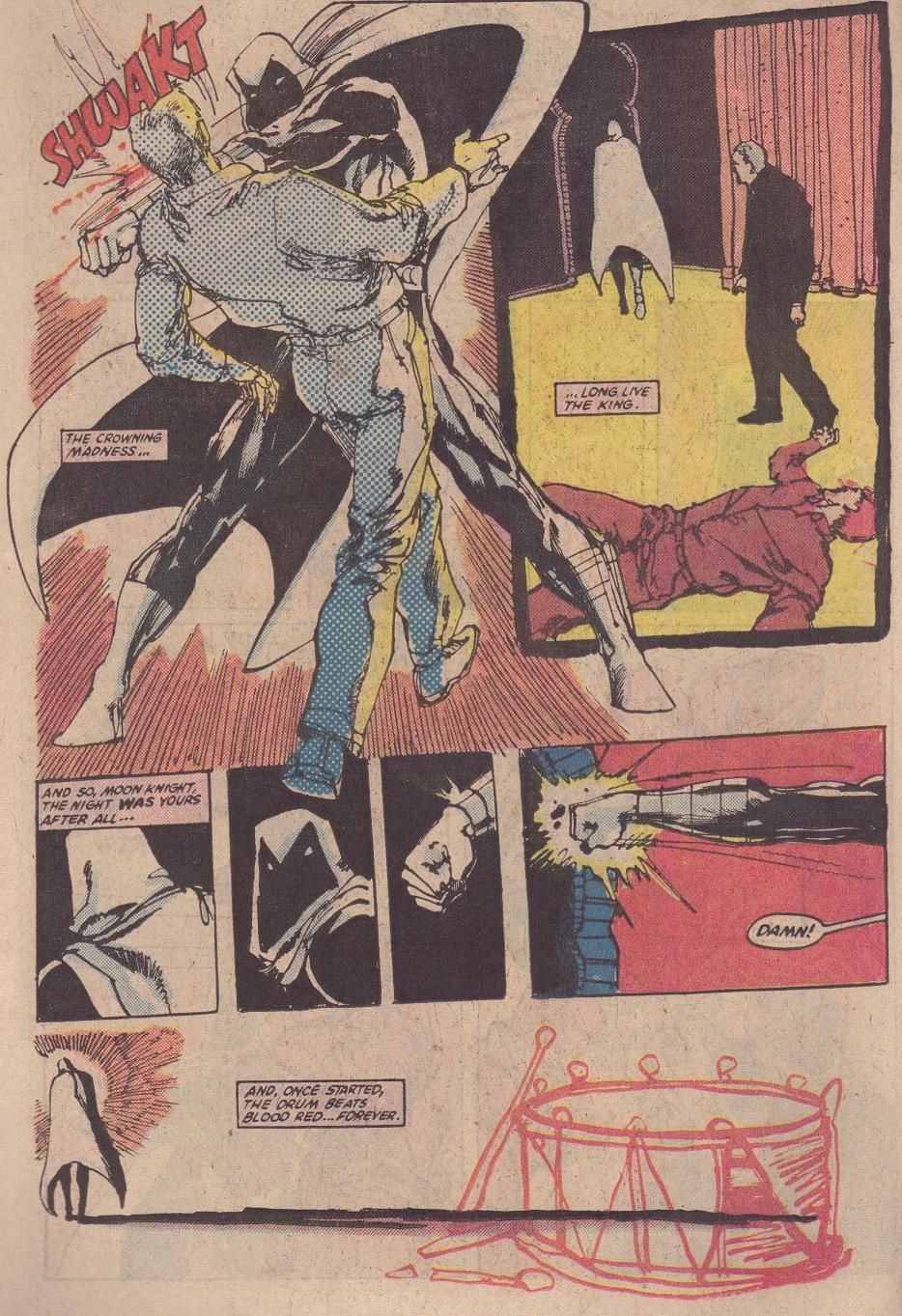

The highlight of the personal stories of the Moench/Sienkiewicz collaboration is "Hit It!" in issue #26. Frankly, it's a bit over-written - Moench could have easily backed off some of the narration and the issue would have had the same impact, but it's still a triumph of storytelling and art melding seamlessly to give us a classic of the form. Moench tells the story of a man who reads about his father's death in the newspapers and freaks out a bit because he hasn't has a chance to "pay [him] back." We find out early on that the man's father abused him, and his rage over not getting his revenge spills over, as he beats people who stand in his way as he heads toward the church where his father's coffin reposes. He even punches the priest who tries to talk to him. Moon Knight, who has followed his trail, appears to stop him, and the man defies him and then breaks down, begging Moon Knight to hit him. Even as Moon Knight turns away, the priest orders him to hit the man. Of course, the man snaps and punches our hero, who has to respond. Even he can't resist the lure of violence, as much as he wants to. Moench does a nice job building the tension, even if he didn't need to repeat "hit it" so much throughout the story, and the final few pages are a brilliant examination of the consequences of violence and the way it is perpetuated through the years. Moench would write other personal stories, but "Hit It!" is a crowning achievement. We don't often see a superhero comic deal with violence and its effects in such a raw manner, so when it's done well, it's impressive.

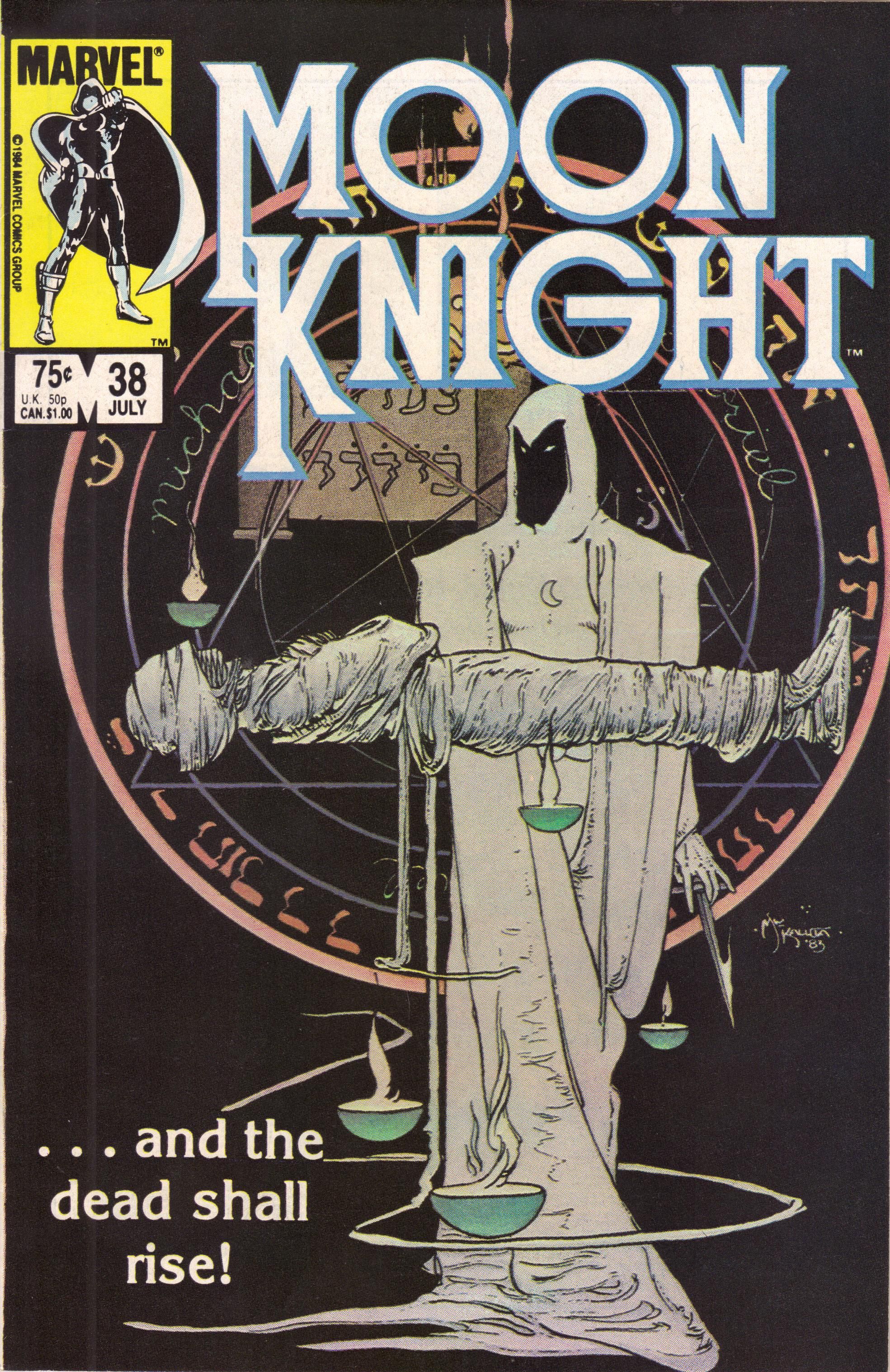

In later issues, Moench would explore other decidedly un-superheroic themes. Issues #31-32 is a story about a gang terrorizing a neighborhood and what happens when one man decides to fight back. Moon Knight has no easy answers for the characters - one gang member isn't a bad guy but he has no future in the neighborhood, while the shop owners are determined to take up arms against the gang, something Moon Knight convinces them is a bad idea. Of course, he uses violence against them as well, and there's the wonderful panel (see left) when he's beating the punks - Nowlan shows just his fist, partly covered with blood, in the foreground, and projected onto the wall behind it is Moon Knight's shadow, viciously beating the gang members. In issue #35, Tony Isabella incapacitates Moon Knight for the third time in the series - the Fly catches him off guard and breaks his back, putting him in a wheelchair. The main plot of the story involves ballet dancers defecting from the Soviet Union and the mutant the KGB sends after them to kill them. She's also a dancer, the former student of one of the defectors, and she kills him in front of the wheelchair-bound Marc, who can only watch. The victim's indomitable spirit as he dies inspires Marc, though, and by the end of the story, he's able to defeat the assassin. In the final two issues of the series, Alan Zelenetz delve into Marc's past again, as his father dies and he needs to sort out his feelings about it. Marc's Jewish heritage comes to the fore in this story, as his father was a respected rabbi who was sorely disappointed in Marc's career choice.

All of these stories, some better than others, give us a very unusual kind of superhero. Marc Spector doesn't have superpowers - there's a vague idea that a bite from the werewolf in his first appearance gave him some extra strength, but that doesn't last long - and Moench decides to separate him from the usual urban vigilantes by telling these kinds of stories. The biggest complaint about Moon Knight is that he's a Batman rip-off - the night-time avenger, the millionaire secret identity, the gadgets - but considering that Batman is a rip-off of pulp heroes, it seems silly to call Moon Knight a rip-off of him. But Moench makes sure to differentiate him from Batman - not only by giving him even more identities, but by making his out-of-costume relationships the most important thing in his life. Unlike Bruce Wayne, Steven Grant has a steady, live-in lover - Marlene Alraune. After the silly first issue, when Marlene is torn between hatred and desire, Moench does a very good job making her a true equal in their relationship - Moon Knight is obviously the hero, but Marlene is often called upon to act in a tense situation, plus she runs Steven Grant's estate for him.

Even in Marlene's first appearance, in Marvel Spotlight #28, Moench writes her as a competent partner to Moon Knight. Yes, she is taken captive by Conquer-Lord, but prior to that, she easily beats up one of Conquer-Lord's flunkies (and the only reason Conquer-Lord captures her is because Moon Knight kicks him into her accidentally). From the very beginning of Moench's return to the character, Moon Knight thinks nothing of enlisting her help to find out what's going on with the Horus statuette in Hulk! #11. Moench puts Marlene in danger plenty of times, and Moon Knight often has to rescue her, but he is the hero, after all, and it's impressive how often Marlene gets out of trouble herself, without waiting for her rescuer. At the climax of "Mind Thieves," she is right in the thick of the fight, keeping the thugs busy by beating them up while Moon Knight fights the main bad guy. In issue #3, she actually saves Moon Knight by shooting Anton Mogart as that villain is about to stab our hero. She rescues Moon Knight again in issue #4, when an assassin named Ice is about to kill our stunned hero. Moon Knight returns the favor a page later when Ice is about to kill Marlene. In the four-part Nimrod Strange epic, issues #17-20, Marlene infiltrates Strange's inner circle - he always keeps three bikini-clad bodyguards representing white, black, and Asian people by his side, and Marlene takes the white woman's place - and she helps thwart Strange's attempt to firebomb Manhattan. As she fights alongside Moon Knight, she also tries to get him to reconcile his past with his present and become a better man. She prefers Steven Grant because he's not as rough as Marc Spector, and Spector's juggling of identities is a constant source of pain to her. After her brother dies in issue #23, she reaches out to her lover but fails to get him to notice her.

Her departure in issue #25, when she goes to work for Carson Knowles, is a bit abrupt, but Moench has laid some groundwork. She returns, of course, and continues to assist our hero in his activities. It's refreshing that Moench makes Spector and Marlene equal partners in the crime-fighting venture, as well as equals in their relationship. They are mature lovers, free from a great deal of angst, fully cognizant that the other in is love, and nothing comes between them. It's by far the most interesting relationship in the book, and it's nice to track how the two of them work through whatever comes up to challenge them.

Marc's relationships with the other members of his supporting cast are important, as well. Frenchie, it seems, gets the short straw when it comes to Marc - he doesn't even get his name until issue #11. But he's still steadfast, and Moon Knight relies on him even more than he relies on Marlene - Frenchie is an ace pilot, and he knows Marc better than anyone. In issue #2, he reveals his identity to Crawley, Gena, and Gena's kids Ricky and Ray (in her first appearance, Gena had a daughter, but she disappeared by the time Gena shows up again) - Ricky and Ray tracked him as Jake Lockley to Steven Grant's mansion, so he had little choice, but it's nice that Moon Knight is so cavalier about his secret identity with people he trusts. These people form his group of agents, and Moench does a nice job showing how their relationships with their boss grow and change over the course of the series. We never see too much of the "agents," but when we do, Moench gives them clear personalities and different reactions to situations based on those personalities.

Of course, all of Moench's good writing might have been ignored if he hadn't been paired with a young artist whose work on Moon Knight was his first comic-book work, his first issue of which appeared when he was not even 21 years old.

Moench had been an interesting writer who took chances before Moon Knight, and it's interesting to wonder how much he would have evolved if Sienkiewicz hadn't evolved right along with him. We get a brief glimpse in The Hulk! #12, as I pointed out, because Keith Pollard's solid pencils are still very much of the time, and perhaps Moench would have kept Moon Knight as a simple action hero with some odd quirks. Even Gene Colan, who provides very moody pencils in The Hulk! #11, didn't evolve much past that style - Colan, of course, was a long-time veteran, so why would he need to change? - and so perhaps the book with Colan would have been more moody and weird, but nothing revolutionary. Sienkiewicz, however, changed his style as the book moved along, and by the end of his run, he was not quite as innovative as he would be on New Mutants, Elektra: Assassin, or The Shadow, and far from the visionary of Stray Toasters or Big Numbers, but he was far more revolutionary than any other artist in mainstream comics. Depending on how one feels about the evolution of Sienkiewicz's style, reading Moon Knight month-to-month must have been tremendously unsettling or truly thrilling, the creation of a master or a slide into madness. Either way, the art and writing work together to push both creators to dizzying heights, which is what you hope for when a writer and artist team up.

Sienkiewicz starts off very much influenced by Neal Adams, which certainly isn't a bad idea. His work already shows a great deal of dynamism, with wonderful choreography and a nice blend of the realistic and the ridiculous. His first villain, Lupinar, is a man born with hypertrichosis, which makes him look almost like a werewolf. Considering that Moon Knight's first villain was Jack Russell the werewolf, he finds a certain symmetry in battling our hero.

Lupinar is a silly villain in many ways, but in Sienkiewicz's hands, he becomes almost scary, and Sienkiewicz gives him an odd noble grace, especially when he duels Moon Knight with swords (a deliberate callback by Moench to the Neal Adams Batman-Ra's al Ghul fight?). Already we can see the confidence in Sienkiewicz's layouts and pencil work, which would only get stronger. In later issues of The Hulk! magazine, he showed how easily he could show the power in Marvel's more mainstream characters (the Hulk himself guest stars in issue #15), and he kept getting better and better at body language. When Randall Spector returns and starts killing, leading up to an attack on Marlene, we never see Moon Knight's face, but Sienkiewicz shows his rage at his brother and his helplessness while Marlene lies in the hospital. We even get a brief glimpse of some of his future stylistic choices - in "Mind Thieves," when Moon Knight is drugged, Sienkiewicz shows us the harrowing visions he sees while he's under the influence. They're small panels, but it shows what Sienkiewicz could do when he let his imagination go wild.

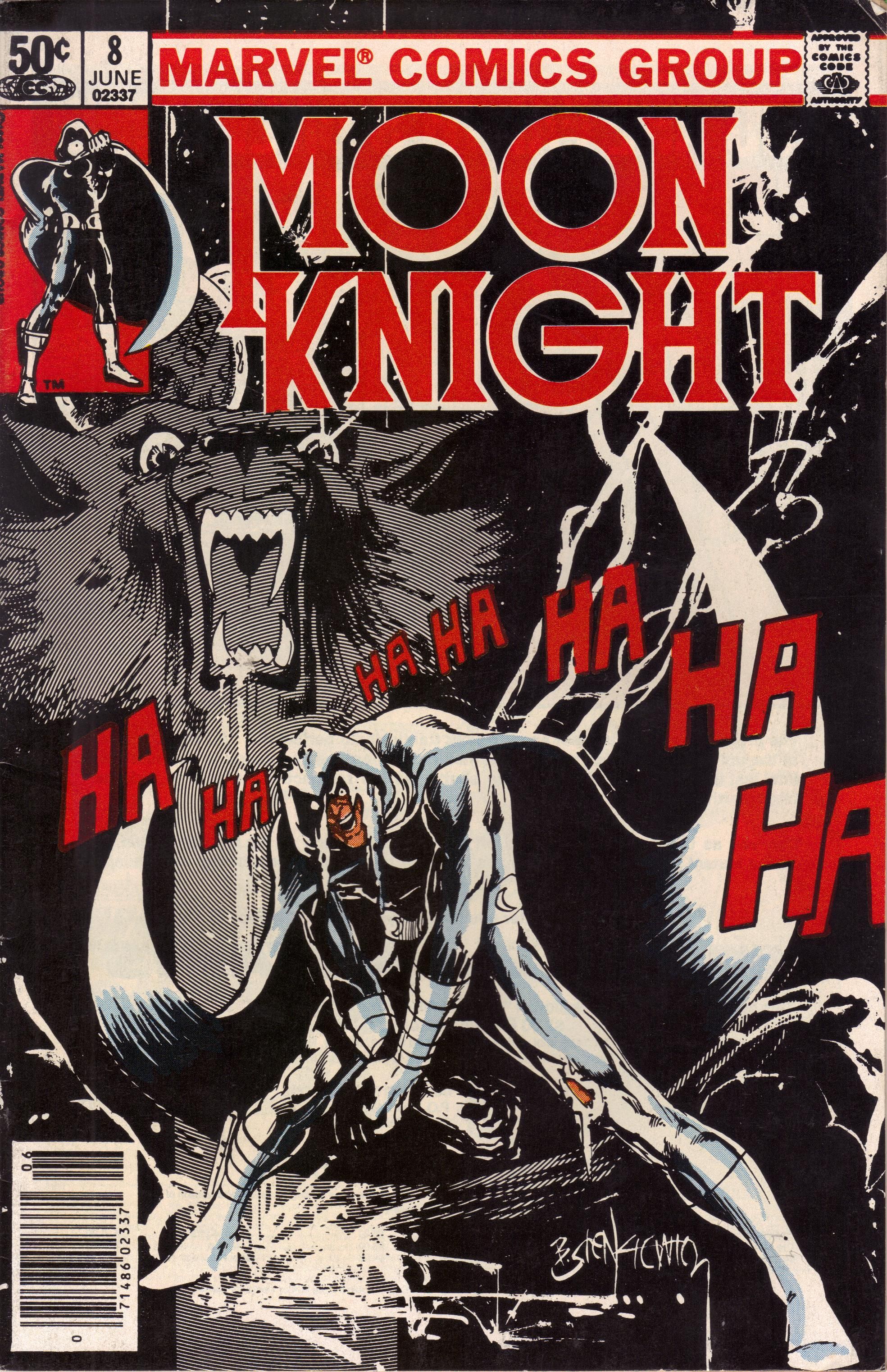

As he moved into the ongoing, his Neal Adams influence began to wane just a bit. In issue #3, Klaus Janson inked him for five issues in a row, and the style shifted slightly. Janson inked him on the Randall Spector epic, but it's interesting that issue #3 on the ongoing has the same cover date as Daredevil #168, when he started inking Frank Miller. Issue #3 retains a bit of Neal Adams, but issues #4-7 are very much more Miller-esque, as Janson smoothed out some of the nuances in Sienkiewicz's faces and hardered the lines, making them much more angular. With an artist like Miller, it worked fairly well, but Janson clashed with Sienkiewicz, so although the art is perfectly fine, it's less interesting than Sienkiewicz's work in The Hulk! magazine and definitely less than his later work. Janson, however, is much better than Giacoia, a very old-fashioned inker (he was almost 60 when he inked his issue) whose work on issue #8 bludgeons any quirkiness out of the pencil work.

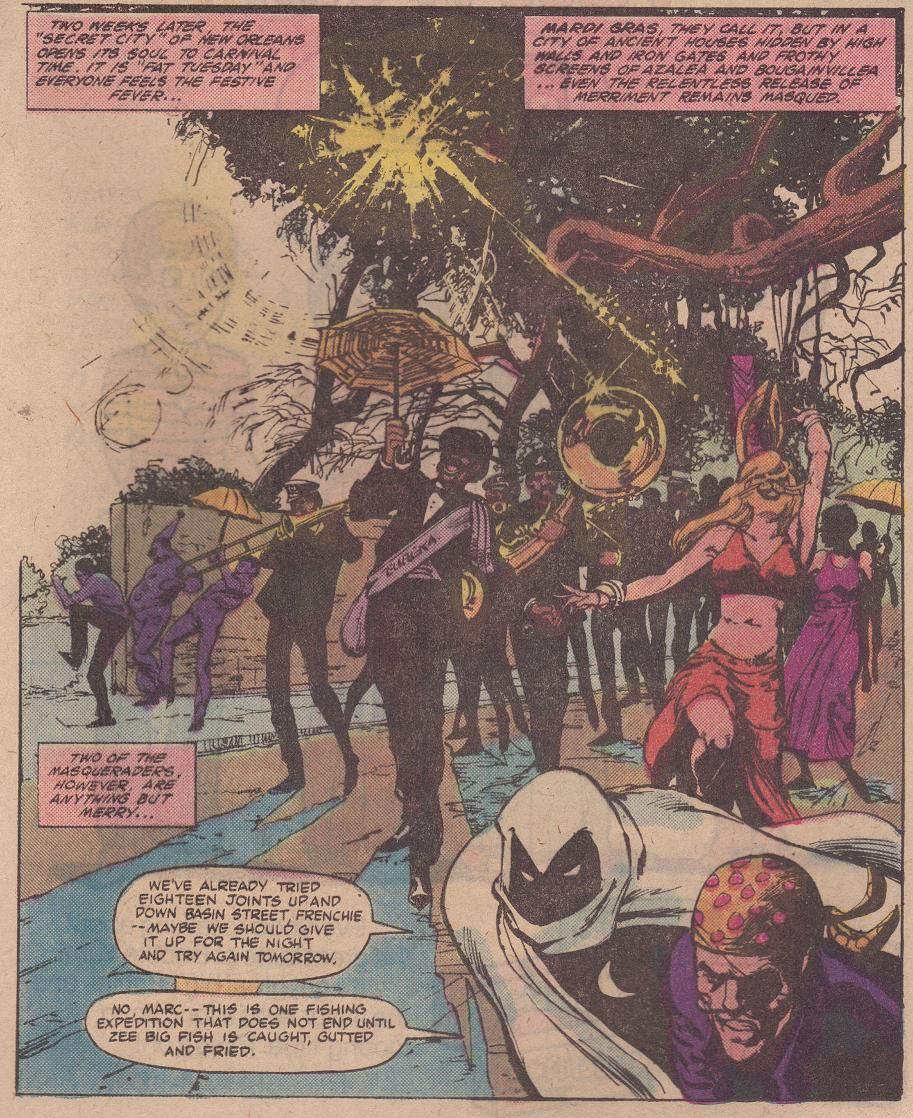

It's amazing to see the difference in the work when, in issue #9, Sienkiewicz inks himself. The dynamism is back, and there's far less Neal Adams, and there's even some hints of the experimentation of the later issues. Sienkiewicz shows this throughout the early part of the run - the final page of issue #7, in which Marlene, under the influence of drugged water, crouches in a bathroom clutching a jagged piece of glass with water overflowing from the taps, is disturbing but weirdly erotic, as Marlene waits for her lover so she can carve him up with her weapon. It's not quite a full-bore "Sienkiewiczian" image, but it's well on the way to his boundary-pushing style. We continue to get glimpses of what's to come in the CCA issues - a full page, nine-panel grid with Anton Mogart in the center square, shooting at each panel as Moon Knight circles around him (issue #9); a beautiful flashback sequence that eschews panel borders and flows out of the package Isabelle leaves for Jean-Paul (issue #11 - see above); a hallucinogenic Mardi Gras scene with what would become a Sienkiewicz staple - more sketchy, abstract drawing evoking a mood rather than a concrete experience (issue #11 -see below); a heavier reliance on light and shadow rather than hard lines (issue #12); more stylized faces (particularly Marlene's early in issue #13); a more hyperactive and "unrealistic" use of motion lines (issue #14); a greater use of stylized sound effects, more extreme body portrayals, and the use of rough, uncolored pencil art to show a heightened emotional moment (issue #15). Even as the art remained firmly within the framework of "standard superhero" (issue #13 features Daredevil as a guest star and the two heroes fight the Jester, of all villains), Sienkiewicz was showing that he was itching to burst beyond what had been seen before.

After a decent fill-in issue (#16), Moench and Sienkiewicz returned with the Nimrod Strange epic ... and Sienkiewicz was not experimenting as much. What happened?

Well, he got a different inker. Right before the one-issue break, he was finally inking himself, but with issue #17, Steve Mitchell came on board for the Nimrod Strange story. Perhaps Moench wanted to do one more big-time action adventure before unleashing the darker stories on the unsuspecting public, and Mitchell's slick style was more suited to that kind of tale. Issues #17-20 are nice to look at, because Sienkiewicz was still able (or willing) to draw in his older style, but it's definitely a reversion to the kind of art of the first eight issues and the magazine stories. Later in the series, Sienkiewicz's art definitely looks more labor-intensive, so it's possible Moench just wanted to get this story out of his system. Issue #21 is a weak fill-in issue (written by Moench and drawn by Vicente Alcazar, it features Moon Knight teaming up with Jericho Drumm to fights zombies and is best forgotten), but the splash page of issue #22, which is the return of Morpheus, shows that Sienkiewicz has stepped up his game even more.

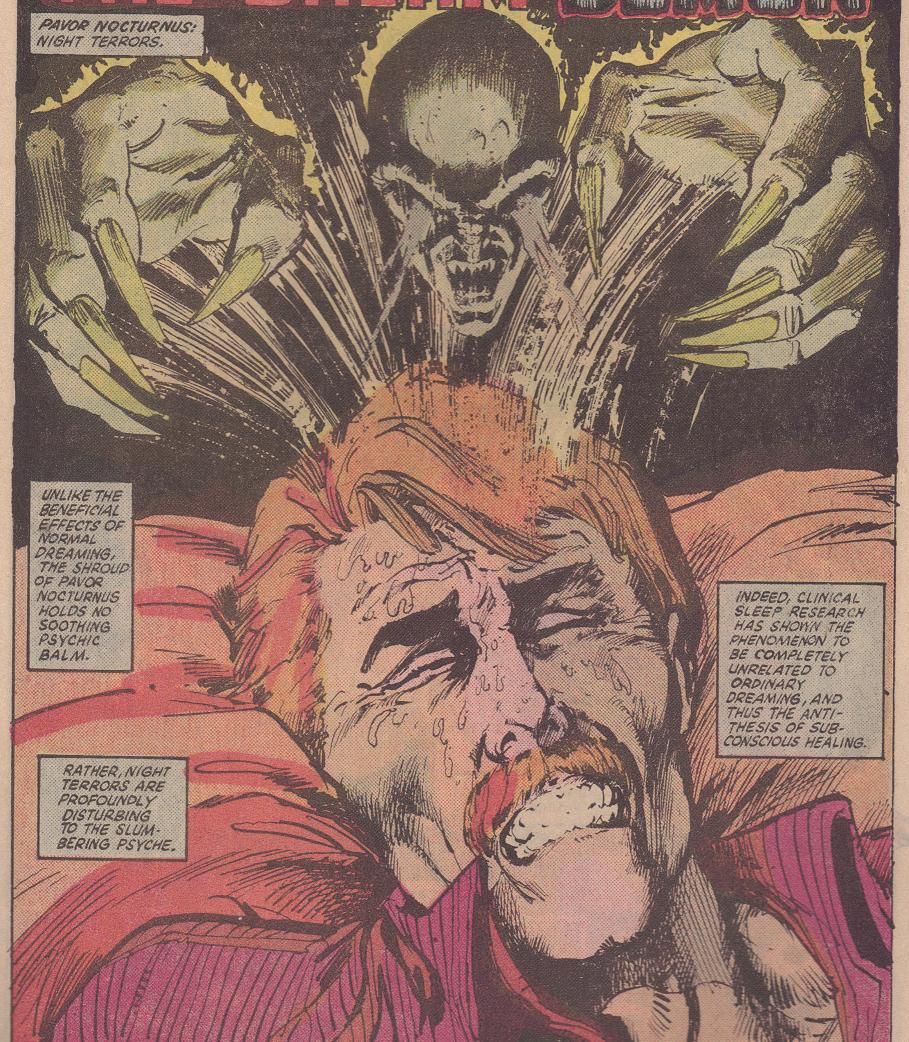

The first page of issue #22 shows Peter Alraune, Marlene's brother, sweating like an addict in bed while a vision of Morpheus floats above him. Morpheus appears to be rising full-blown from Peter's brain (which, indeed, he is, as Peter is dreaming), his eyes flashing green flame and his hands, larger than his head, reach toward the doctor.

Just so we know that this is not a fluke, on the next page Sienkiewicz shows Peter melting away into a terrifying skeleton, his eyes surrounded by deep black circles and his teeth rotting. In just a few pages, Sienkiewicz shows that he has moved to a new level, and while his art in the first 26 issues of his run is very good, bordering on spectacular, the final 8 issues are a tour-de-force of a new kind of art, one that took comics to heights that very few people imagined they could reach and which many artists cannot conceive of approaching. If that sounds like hyperbole, we need to consider what mainstream comics looked like in mid-1982 and what they generally look like even today. Very few artists on a mainstream superhero comic today, 30 years later, make any effort to push the envelope as much as Sienkiewicz did. His art on these latter issues of Moon Knight and in his later works still looks ahead of its time, which is as much a testament to his genius as it is an indictment on many artists working in his wake. Later in issue #22, he takes Moon Knight into a nightmare world, colored sickly green by Christie Scheele (an able partner to Sienkiewicz on these issues), where he uses odd camera angles to heighten the weirdness, even heavier shadows to place Moon Knight beyond the pale, and the incorporation of the natural world into his panel borders (in issue #23, water forms the borders when Moon Knight is pushed into a lake).

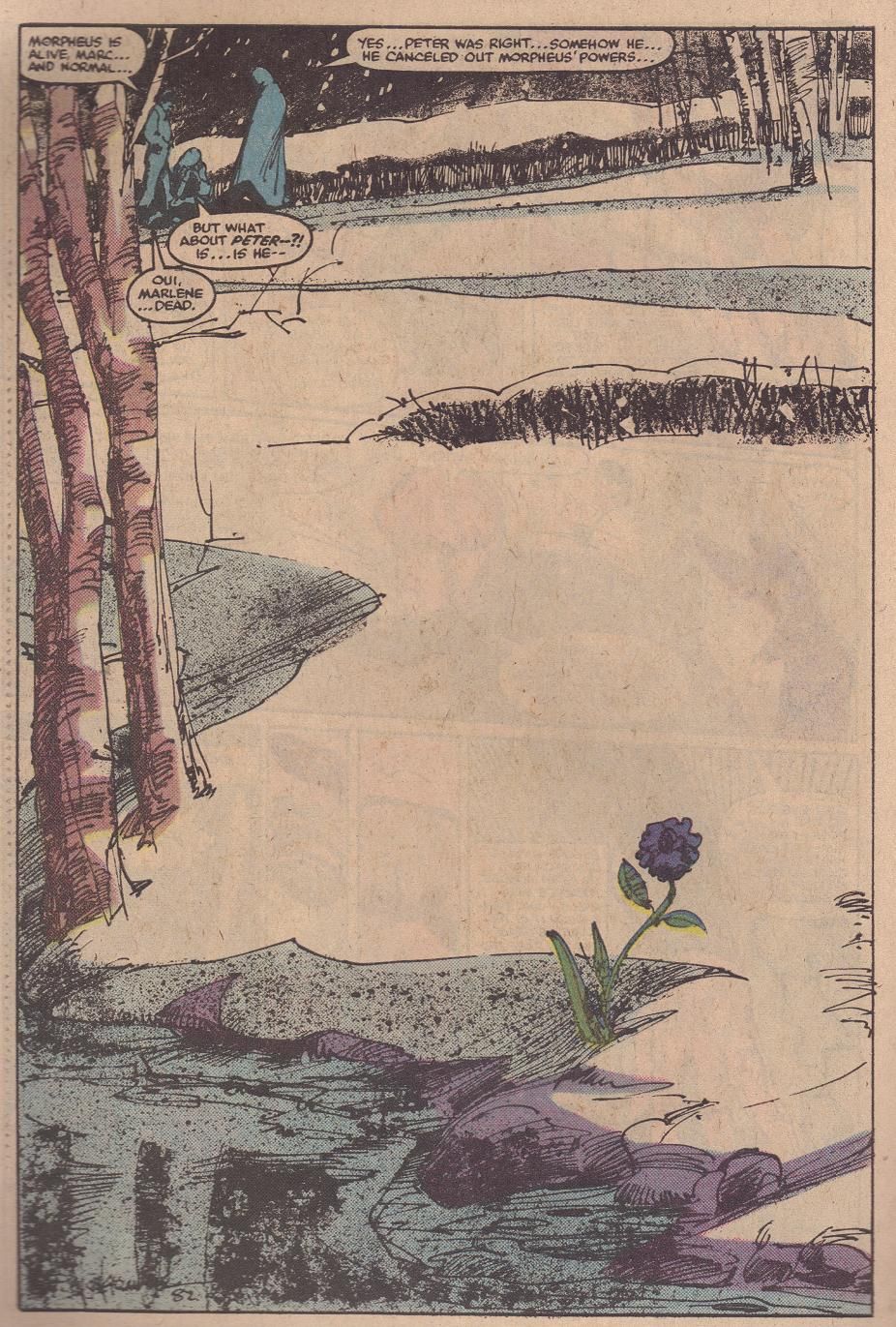

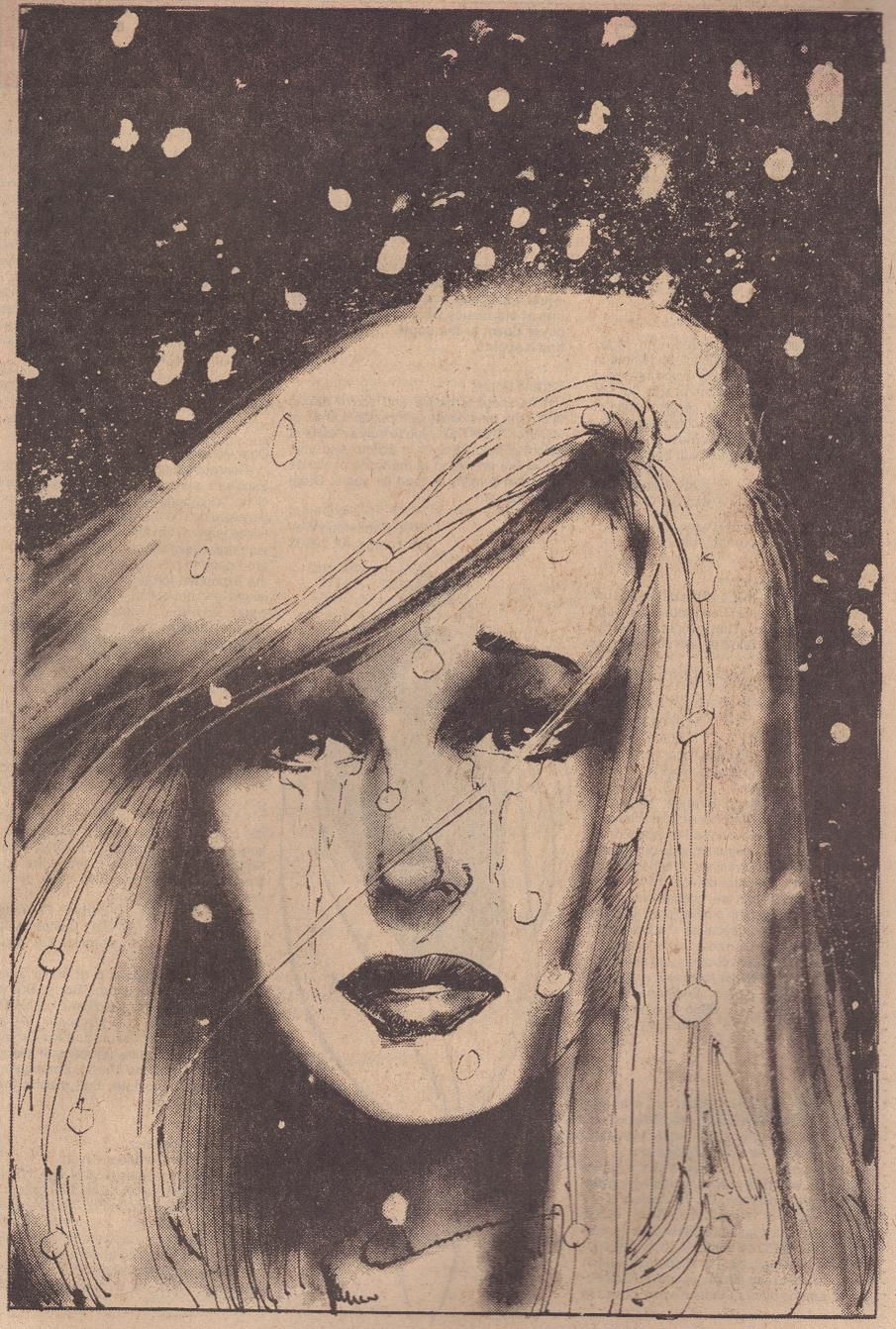

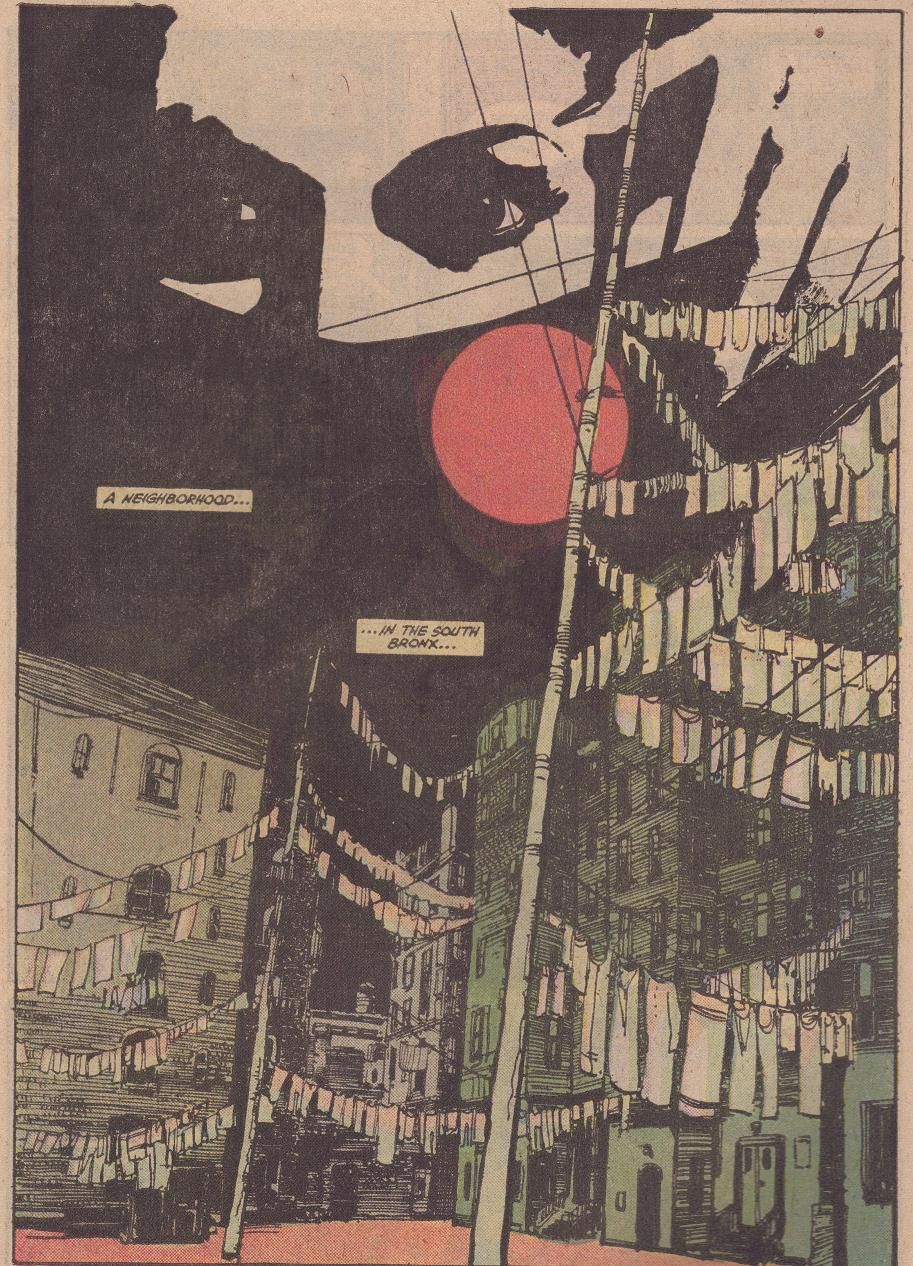

He begins to experiment much more with large areas of negative space, using it in issue #23 to raise the feeling of isolation as our heroes are stalked by Morpheus in a snowstorm. He experiments with Zip-A-Tone to create different moods, and the final two pages of issue #23 are amazing: the first shows the characters isolated in the upper left as Marlene learns her brother has died, and Sienkiewicz fills the entire page with the vast wasteland of snow, with a solitary purple flower struggling against the cold in the foreground; while the final page is a black-and-white drawing of Marlene crying as snow falls around her. These are two tremendous images, and in issue #24, Sienkiewicz begins the story with yet another splash page - this time of a tenement in the South Bronx, ghostly white shirts strung across lines criss-crossing in front of run-down buildings, and a negative space image of Scarlet Fasinera hovering above it all, with a blood-red sun almost in the center of the scene. Sienkiewicz continues to push the envelope even in relatively simple panels - when Scarlet challenges Moon Knight's morality by asking whether he'd rather have her, a killer of criminals, or her target, a drug pusher, on the streets, Sienkiewicz places Moon Knight in the lower right in shadow, another blood-red sun directly on his shoulders, burdening him, while in the foreground, the silhouettes of the graveyard fence loom up, forming a cage, locking Moon Knight into his worthless moral pattern. The fascinating thing is that Sienkiewicz never sacrifices storytelling technique - his layouts are as clear as ever, and when Moench gives us a fairly straight-forward story, such as Black Spectre's in issue #25, Sienkiewicz easily tucks in some experimentation but still tells the story clearly.

Here are some of the splash/full pages by Sienkiewicz:

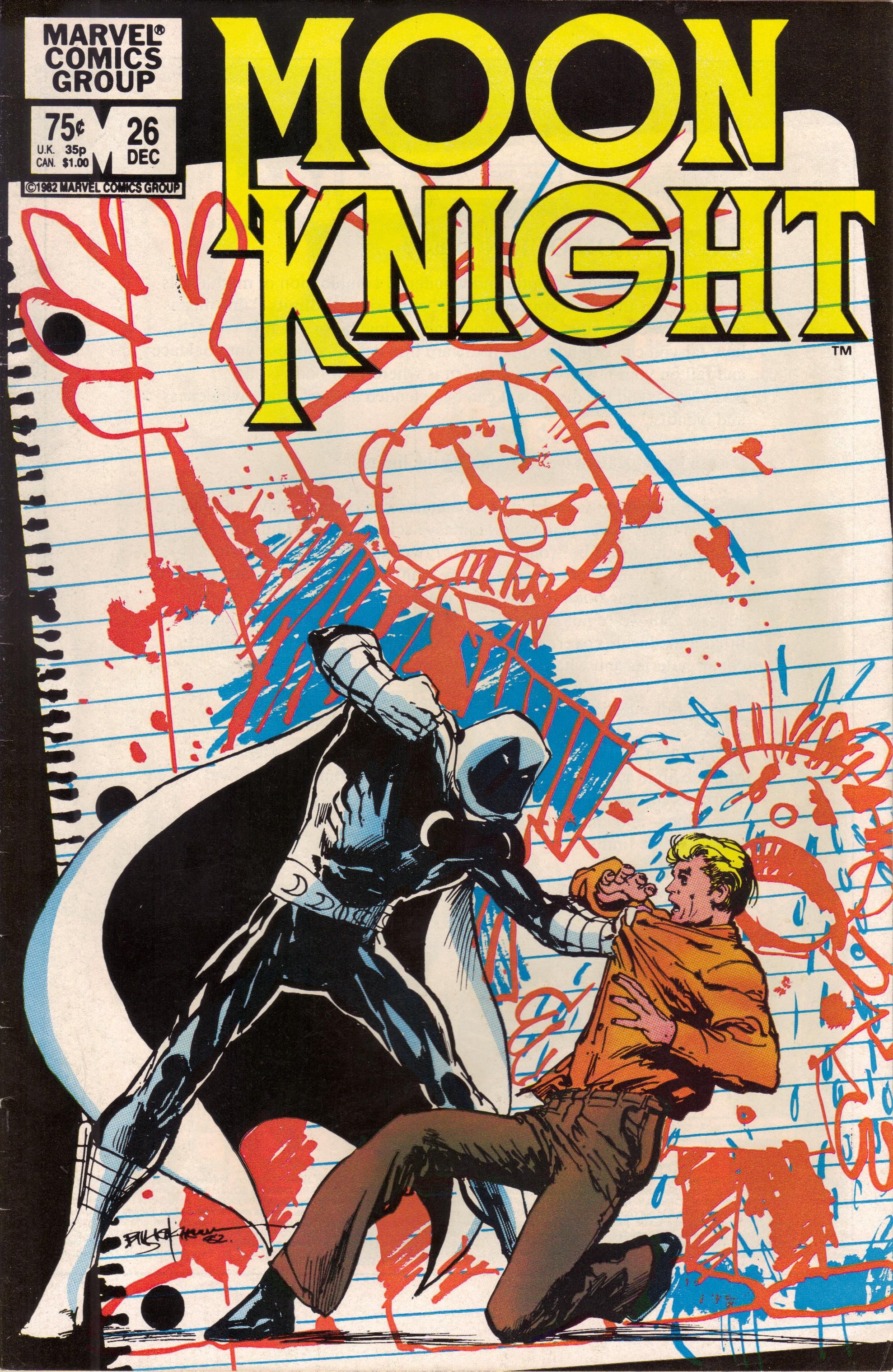

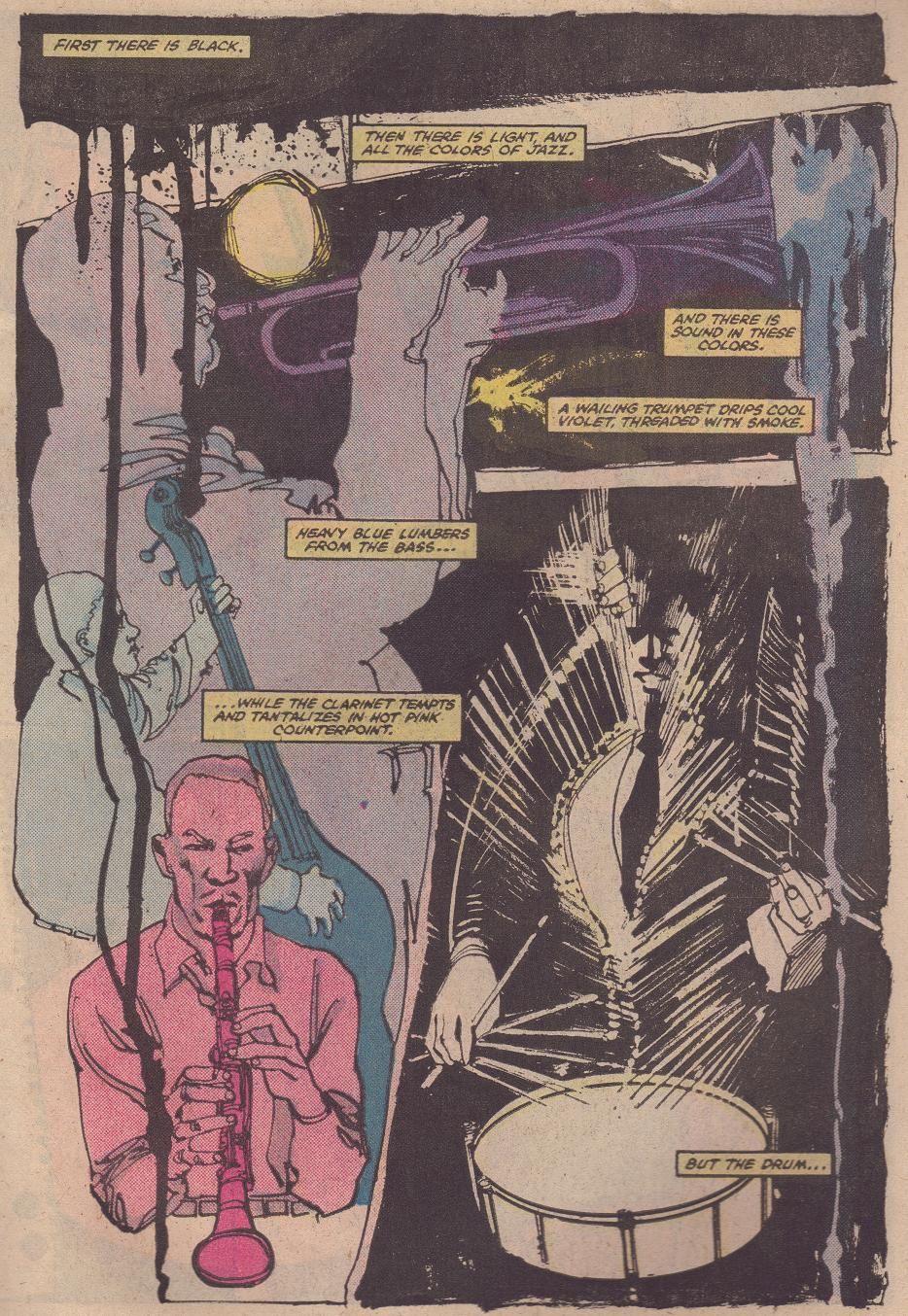

As noted above, issue #26 is the high point of the collaboration. Sienkiewicz's cover leaps off the rack, as Moon Knight clutches what looks like an innocent man who cowers in fear from the inevitable beating. This image of Moon Knight as bully is reinforced by the child's drawing behind the two men, showing an angry man about to hit a defenseless boy. Sienkiewicz leads off the story with abstract images of a jazz band beginning to play, then gives us a two-page spread showing how the verbiage of violence - "hit it" - are prevalent in our society. Moench wrote the script, of course, but Sienkiewicz's riot of images pumps up the tension of everyday life. As the unnamed brute runs through the city toward his father's final resting place, we keep seeing the crude drawing of the father beating the son, so we know before Moench tells us what has happened (it's here where Moench could have pulled back on the writing a bit, as Sienkiewicz shows us all we need to know). Moench allows Sienkiewicz to equate Moon Knight with the father, a wonderful touch showing that for all his heroics, he can be a bully as well. It's a short story (16 pages), but it's a brilliant jazz riff of a comic, shot through with hectic music and poetry, and it shows how far Sienkiewicz has come as an artist. Here are the final, brutal pages of issue #26 (and yes, that's Robert Plant on the first page - don't ask):

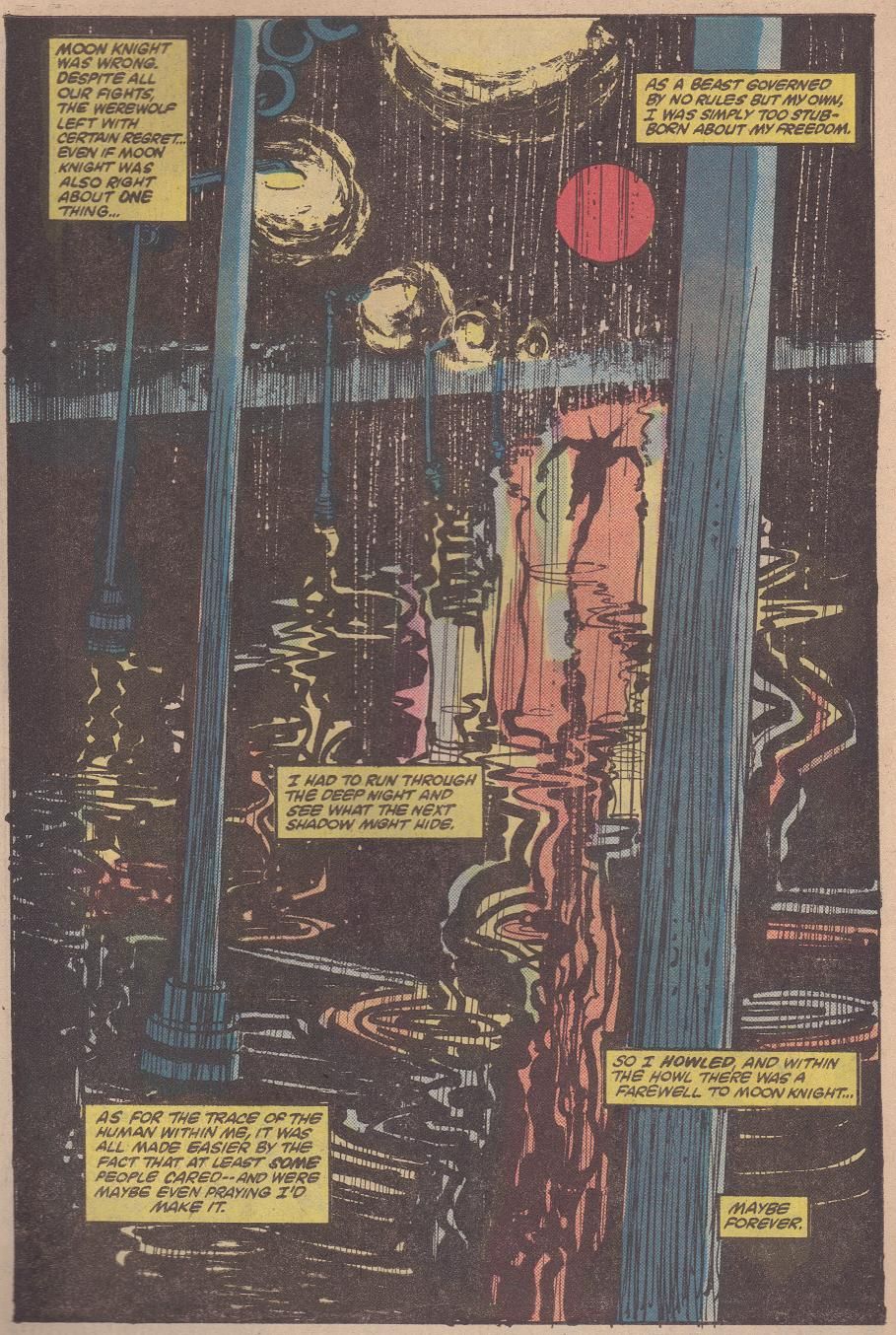

Sienkiewicz's final three issues don't quite come up to issue #26's level, but they show that Sienkiewicz wasn't coming back from where he had ventured, art-wise. Issues #29-30, his last ones, feature Jack Russell, the werewolf, who is being hunted by a group of Satanists who want to use the werewolf to prove theirs is the true faith. It's a slight story, but Moench writes it well and Sienkiewicz drenches it in darkness, suiting the subject matter. He continues to try different tricks - re-using panels to show repetition, for instance - and the final few images, of Moon Knight standing in the rain and the werewolf running into the night, are as strong as any in the run. Sienkiewicz said that he had gone as far as he could go with Moon Knight, but the journey was well worth it.

Although the final issues gave us some very good stories, the book floundered without Sienkiewicz. Kevin Nowlan was supposed to be the new artist, but he drew only three full issues and half of another one before leaving. Moench's final few stories, issues #31-33, were as good as any he had done before, and Nowlan's fine lines, while a dramatic shift from Sienkiewicz, showed a great deal of potential, especially in the sequence where Bora kills Sergey, the ballet dancer, in issue #35. The issues you should own - #36 is excluded because it's not very good and signals a shift from a more urban, gritty Moon Knight to a slightly more mystical one, a shift which never worked - are in the similar vein of how Moench portrayed the character - trying his best to fight bad guys while struggling with being a good guy himself. This is most clearly delineated in the final story, where Marc must come to terms with the fact that his father had a surrogate son, a student who was closer to Rabbi Specter than he ever was. The series might have staggered to the finish line as it went to a bi-monthly schedule, but Tony Isabella and Alan Zelenetz did write some strong stories on the way out.

Moon Knight was influential for many reasons, and just its influence should raise its profile among comic book fans. Even without the new way of distributing it or the experiments with format, however, the first volume of Moon Knight is a tremendous comic book, coming along at just the right time when fans of the early Marvel comics were growing up and wanting more mature storytelling. Moench took a rather second-rate character and pushed him and his cast in directions no one saw coming, and the series' influence on subsequent "mature" takes on superheroes shouldn't be underestimated. Meanwhile, Sienkiewicz was smashing the boundaries of what mainstream art could look like, blending his formidable storytelling and simple pencilling skills with an unbridled imagination, as he wondered what you could do with different media and different tools to make the art dazzle in ways that had rarely been seen before. It's not surprising to see him using more and more mixed media as he moved forward - he had already begun it in Moon Knight. His evolution, paired with Moench's more experimental scripts, made Moon Knight stunning when it first came out and is a reason why the book hardly seems to have aged. Moon Knight remains ahead of its time, and far too many artists still stand in its shadow.

Marvel has published two Essential volumes collecting Moon Knight's pre-ongoing appearances (excluding his brief stint with the Defenders) and the 30 "Sienkiewicz" issues of the regular series (I haven't seen volume 2, but I assume it includes issues #21 and 27, which are not that good but help throw Sienkiewicz's art into stark relief). The company also recently brought out a collection called Countdown to Dark, which reprints the Moench/Sienkiewicz back-up stories from The Hulk! It costs more, but it's in color, if that's your thing (the original stories were in black-and-white). Sienkiewicz's early work in the first Essentials volume looks okay in black-and-white, but I don't know how the later stuff looks. It would be nice if Marvel brought these out in trades (perhaps a few "Visionary" volumes?) because Christie Scheele's coloring really complements Sienkiewicz's work nicely. Even if they don't, you can read these in the Essential volumes (and, presumably, the rest of the series won't be collected) or find the back issues, which do have some interesting letters and editorials. Either way, if you want to read brilliant stories and watch a master blossom right before your eyes, you need to own Moon Knight. Would I steer you wrong?

As always, you can check out the archives for more groovy comics. Don't be shy!