Firestorm? Firestorm???? Yes, Firestorm. Two words: "John" and "Ostrander." Read on! But look out for SPOILERS!

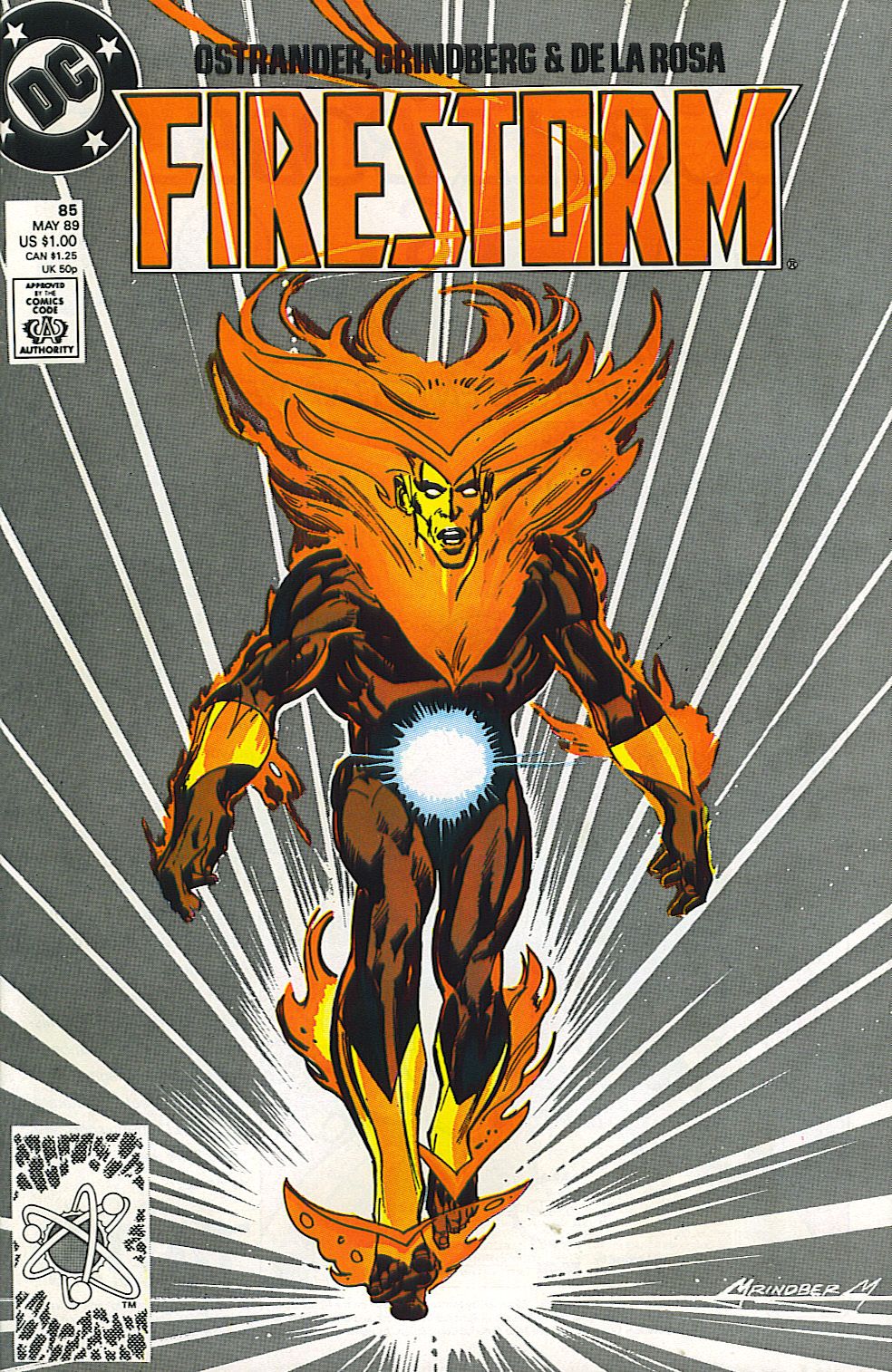

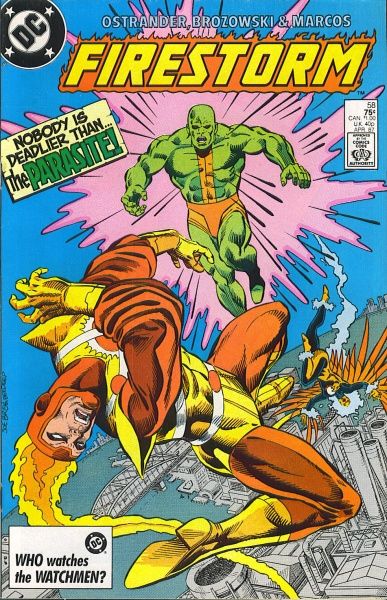

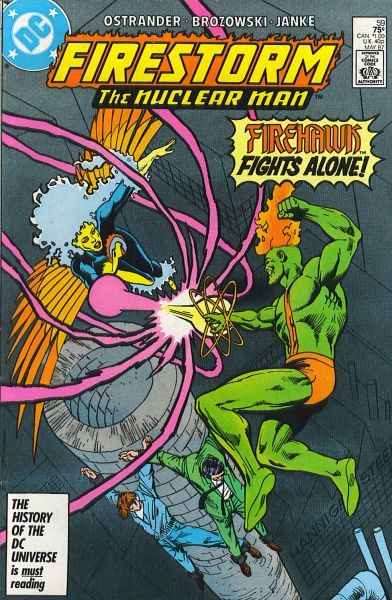

Firestorm by John Ostrander (writer, issues #58-79, 81-100, Annual #5), Robert Greenberger (writer, issue #80), Gerry Conway (writer, issue #100), Joe Brozowski (penciller, issues #58-64, 66-67, 69-79, 100,Annual #5), Ross Andru (penciller, issue #65), Richard Howell (penciller, issue #68), Tom Grindberg (penciller, issues #80-85, 100), Tom Mandrake (art, issues #86-100), Al Milgrom (artist, issue #100), Pablo Marcos (inker, issue #58), Dennis Janke (inker, issues #59-60, 68), Dick Giordano (inker, issues #61-63), Sam de la Rosa (inker, issues #64, 66-67, 69-85), Alfredo Alcala (inker, Annual #5), Arne Starr (inker, issues #81-82), Carlos Garzon (inker, issues #98-99).

DC, 44 issues (#58-100, Annual #5), cover dated April 1987-August 1990.

In the pantheon of great comic book writers, John Ostrander rarely gets mentioned, and that's a shame, as he is one of the best mainstream writers of the past 25 years. In that time, he has given us a wonderful creator-owned series (GrimJack) plus the definitive version of both a DC team (Suicide Squad) and two DC characters (The Spectre and Firestorm). With the advent of the Internet, he has begun to get more credit, but why is it that he has been so underrated? My answer is that he's not terribly flashy. He simply writes excellent stories, without a lot of the bells and whistles that other writers use (I'm thinking of the Brits, of course, but a lot of other writers use them as well). He doesn't do a lot of wacky stuff, and when he does write odd characters, they're not odd in a Morrison-esque way, where you marvel at the sheer audacity of creation, but they're odd in a way that they fit into a, frankly, odd DC Universe. Ostrander doesn't really push the envelope with what you can do with the comic book form. Instead, he writes stories that might be just as important - pushing characters forward and changing them for the better. He realizes that truly great comics come about when the writer lets the characters change, and that's pretty rare among mainstream scribes. He's also not flashy with his prose - his writing doesn't read like epic poetry like some of the other greats of the field. Finally, he was writing for DC at a time when, according to Brian, the royalty package was skewed, so apparently it would take a chunk of money to get his work reprinted in trade paperback. Thus, of the three masterpieces he wrote for DC, only the first four issues of The Spectre have ever been collected. And that's a shame.

Of allOstrander'soverlooked works, Firestorm is the most overlooked, probably because it's not as good as the other three. That doesn't mean it's not an excellent comic, but it suffers from inconsistent art for the first 20-some issues (until Mandrake came on board) and from the fact that Ostrander took it over mid-run (he wrote both Suicide Squad and The Spectre from their inception to demise). Therefore, he couldn't really put his stamp on it from the beginning and had to clear the decks a bit early on, which may have put off long-time readers. The fact that he started in the middle of the run meant, as Dan Raspler put it in his announcement of the book's cancellation in issue #99, that new readers would be daunted by picking up a book with issue #58 if they hadn't read the first 57. The idea of stopping a title and beginning with a new #1 hadn't yet occurred to the Powers-That-Be, which is what they would do today. This was back in the days when "completists" were much more likely to drive the market than they are today, when people tend to follow creators. So Raspler's point makes sense. However, the ironic thing about this comic is that there is absolutely no need to read the previous 57 issues. Ostrander fills us in ably on what has come before, and then takes the book where he wants to go. When he does bring up elements from Firestorm's past (most notably Firehawk and Killer Frost), he does so in a way that we aren't in the dark. Part of Ostrander's genius is that he easily places his stories within continuity but you don't need to know everything about continuity to read his stories. When Red Tornado shows up in issue #91, Ostrander gives us a quick sketch of who he is and what his recent history is, and fits it all into the story he's currently writing. So instead of a writer digging through the past in order to find story ideas, Ostrander simply writes new stories that happen to fit into the DC Universe as a whole.

Ostrander took a fairly dull character with a lot of potential and realized that potential. The idea of two people merging to form Firestorm is a good idea, and Ostrander decided to see what he could do with it. One of the themes of his run on Firestorm is the question of who is "real" - is the Firestorm identity an actual sentient being, and therefore does it deserve its independence? Firestorm had, for a long time, been Ron Raymond with Martin Stein talking to him in his head, but Ostrander blew upthat arrangement and forced us to consider that perhaps "Firestorm" existed independently of both Ron and Martin. What then to do with him? Ostrander delved into the true nature of the creature, and this is where he really hit his stride and made this a classic comic book. Early on in the book (issue #62), he introduces Mikhail Arkadin, a worker at Chernobyl, who experienced a similar accident to the one that created Firestorm and has become a creature of flame. When Firestorm demands that the Americans and Russians destroy all their nuclear weapons or he will, the Russians send Arkadin after him (with the cooperation of the Americans). They really only want to get the two of them in the same place at the same time so they can kill bothcreatures with a nuclear missile. In the process, Ron and Mikhail become Firestorm,and Martin Stein is seemingly killed. However, Firestorm is now a third entity, and Ron and Mikhail, who can communicate with each other telepathically, now must agree to form him. When he does form, he has hisown personality and desires. As Ron and Mikhail only form Firestorm when there's a crisis, he wonders if his only purpose is tofight.This is a key moment in the lifespan of Firestorm, because it allows Ostrander to get into several things that interest him - namely, the abuse of power in the world and how humanity is killing the Earth. Firestorm wants to usehis powers for good, and when Ron visits East Africa, he sees anopportunity for Firestorm to do just that. In issues #77-79,Firestorm terraforms a segment of the desert into a Garden of Eden, but it all turns sour all too quickly, as the various factions in the country fall on this prime real estate and begin killing each other to possess it. We'll get back to that, butas far as Firestorm's development is concerned, this is a crucial story because a native, Jama, becomes part of Firestorm briefly. Ron doesn't know how or why this happened, and the mystery about whatFirestorm actually is deepens.

The Invasion mini-series provides Ostrander with another piece of his puzzle.As I've pointed out, Ostrander makes good use of continuity, which means crossovers. His first (non-essential) work on Firestorm was a two-issuecrossover with Legends, and during his tenure on the book he worked his ongoing themes into the Millennium crossover, the Invasion crossover, and the Janus Directive (although the latter doesn't really count, as Firestorm is barely involved). None of those crossovers is essential to dealing with Ostrander's core title, and the Invasion gives Ostrander the next step in his evolution of Firestorm. In issue #83, we learn that Firestorm was knocked out by the gene bomb released by the Dominators at the end of the Invasion, and while he was recovering, the Russians took some of his DNA. They cloned Firestorm and created their own creature - Svarozhich, named for the Russian god of fire. Svarozhich escapes, naturally, and destroys the melding of Ron and Mikhail, leading them to the home of Gregori Rasputin (who may or may not be the historical Rasputin), who reveals to them the Secret History of Firestorm!

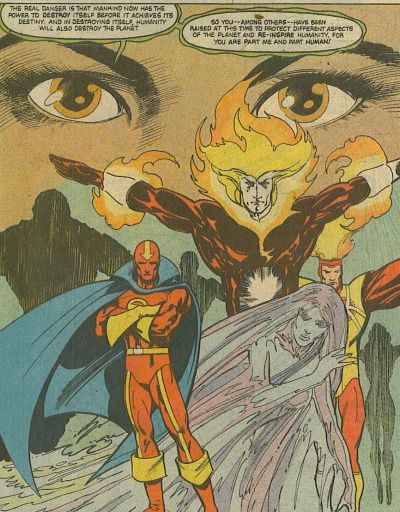

This kind of retcon has been done before and will be done again. Ever since Alan Moore showed us that Everything We Believed About Swamp Thing Was Wrong, writers have been trying to "fix" characters that don't make a lot of sense. Some succeed, some fail. What Ostrander does is "fix" Firestorm by using the Swamp Thing template. This might be another reason why Ostrander's run on the title doesn't get mentioned very often - do people believe it's a rip-off of Moore? Possibly, but it makes sense if you think about it. Moore's successors on Swamp Thing established him as the Plant (Earth)Elemental, so it stands to reason that there should be an Air, Fire, and Water Elemental. As Red Tornado was turned into the Air Elemental, why shouldn't Firestorm be the Fire Elemental? The idea that Firestorm is an imperfect Elemental because Ron Raymond got in the way is a brilliant twist. Ostrander explains that Martin Stein was supposed to be the avatar of the Fire Elemental, just as Alec Holland was the avatar of the Earth Elemental. Ron Raymond got in the way, and because he was conscious when the explosion that created Firestorm occurred, he became the dominant personality. Each incarnation of Firestorm has been flawed, because the conditions for its creation were not perfect. Now that Svarozhich is loose, he has taken the Fire Elemental's powers because he is closer to the pure elemental than the merging of Ron and Mikhail. Ron and Mikhail manage to convince the Fire Elemental - Firestorm - to merge with all three of them, and they become the best incarnation yet - which also means that Ron and Mikhail no longer exist independently. We learn later that even this form of Firestorm is not the way it's supposed to be. Martin Stein is still supposed to be the avatar for the Fire Elemental. Brimstone, a creation of Darkseid during Legends, was thrown into space by Firestorm in issue #76. By issue #100, he's grown to the point where he can throw solar flares at Earth, which will destroy it. Martin Stein contrives to destroy the latest version of Firestorm and make sure he's the avatar that the Fire Elemental imprints on, creating the true Firestorm and allowing him to fly to the sun to battle Brimstone. After defeating the villain in a climactic battle, Firestorm is sucked through a miniature black hole on the surface of the sun and enters a new universe. That's where the story ends - with Firestorm out of the picture, and Ron and Mikhail returned to their lives.

The rather convoluted road Ostrander follows to get to Martin Stein as the true Firestorm is necessary for a couple of reasons. First, it allows him to make sense of Firestorm's origin as presented by Conway and Milgrom. Second, it allows him to delve into one of the two major themes of his run: the quest for identity. The major characters go through transformations both physical and mental, and the two main characters, Ron and Firestorm himself, have to discover things about themselves in order to grow up. During the run, Ron reunites with his estranged father, Ed, who attempts to build a relationship with him. Ostrander unsubtly makes the point that Martin is far more of a father figure than Ed ever was, but Ed tries to make up for that. Ron goes from a somewhat selfish young man to a caring individual who tries to do the right thing. Hebegins this in issues #62-65 (with the Annual forming the fourth part of the story, between #64 and 65), as I've mentioned,when he orders the governments of the world todestroy all their nuclear weapons. But this is still just fighting, and Firestorm isn't the catalyst - Ron is. Firestorm's quest really begins in issue #77, when Ron visits East Africa with his father. Although he tries to do the right thing there and fails, the idea of not sitting on the sideline and getting actively involved as Ron Raymond takes hold within him. This, in turn, fuels Firestorm's desire to get involved. When Firestorm becomes the Fire Elemental, his desire for change takes on a far more aggressive stance. In issue #86, he takes the battle to the enemy and challenges Vandermeer Steel in Pittsburgh to change their ways because they're polluting the Earth. These final issues of the series allow Ostrander to get on his soapbox and preach about pollution, but as usual, he does so ina way that doesn't make things easy. Firestorm simply wants Vandermeer to change how they do business or shut down. If they don't, he'll shut them down. Vandermeer, of course, fights back, calling on the Sunderland Corporation to "loan" them a superhero, Maser (Hal Jordan's nephew) to battle Firestorm. When Firestorm comes back, Vandermeer enlists Firehawk to fight. Throughout these fights, Ostrander keeps bringing up the point that it's not as easy as Firestorm thinks. What about the people who work for Vandermeer and their families? What about the destruction Firestorm himself is causing during his tirades? Firestorm proclaims that he is a force of nature and therefore isn't subject to man's laws, but Maser almost kills him. How can a force of nature die? Firehawk points out that part of Firestorm is still human, and he needs to consider that humanity is part of the Earth, even if they're destroying it.

Firestorm's quest for identity takes another turn when a newly-created Water Elemental, Naiad, enlists Red Tornado to declare war on humanity. Firestorm and Swamp Thing team up to stop them. Firestorm has a chat with the Spirit of the Earth, Maya, who tells him that humanity's destiny is to leave the planet, and because their restless spirit has turned away from space, they are consuming their home. She also tells him that his creation was a mistake and that Martin Stein was meant to be the avatar for the Fire Elemental. Maya inspires him to be an example to humanity rather than an enemy, and also makes him wonder how he can reconcile his search for identity with the fact that his creation was flawed. These two things lead to the big finale.

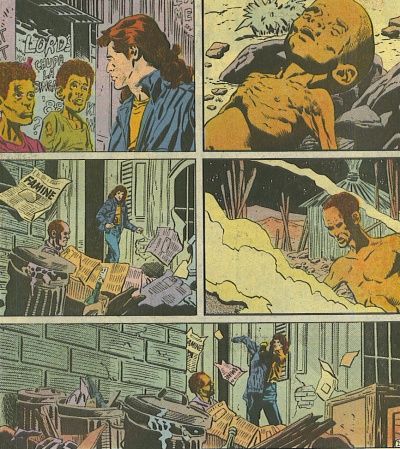

Another reason Firestorm, like many Ostrander comics, is so good is because he's very interested in bringing "real-world" events into his comics. It dates them, sure, but it also allows Ostrander to examine how a superhero would have an impact on the political reality of the world without being so obvious about it, like certain higher-profile creators have done. When someone like Ellis or Millar writes The Authority and shows how superheroes would rip the fabric of society, it's a big flashy mess because that's really the whole point of the exercise. Ostrander simply incorporates it into the bigger story he's telling without a big fuss, and therefore it feels more natural. It also gets fewer headlines, but that's the way it is. Ostrander also does a very good job with setting Firestorm in the bigger world than a fictional city that is just a substitute for New York. Ron and Martin live in Pittsburgh, and many of the big events of the run take place in Moscow (and Las Vegas, but fewer events occur there). Again, Ostrander doesn't make a big deal about this, he just writes the story the way it should occur, and therefore Firestorm gets caught up in international politics. He's the catalyst, obviously, as he gets the Russians' attention by demanding they destroy their nuclear arsenal, but this leads to his merging with a Russian man, which draws him into Soviet politics. Ostrander is also very good at either creating or using superbeings from other countries, and in this comic, the Soyuz (five Russian teenagers with powers) and a Cold War bad guy, Stalnoivolk, play important roles. Ostrander is perfectly comfortable using superpowered beings from other countries, which only adds to the feeling of "realism" in his comics. The fact that this was the era of glasnost and the Soviets are adjusting to Gorbachev's movement toward greater freedom is touched upon, too. They are still rivals of the United States, but they often recognize that Firestorm is a greater threat to both of them. Early on, the rivalry between governments is more prominent, but as Firestorm growsinto his role asEarth's protector, we see other aspects of international politics. The most tragic story in the book is "Eden," the three issues (#77-79) in which Firestorm creates a garden in East Africa. I've mentioned this above as part of Ron and Firestorm's journey of identity, but it also showsthe way in which Ostrander gets out of the puzzle of why superheroes don't do more to solve the world's problems. Firestorm doesn't give the standard reason of "normal people need to work it out for themselves" - he actively attempts to change things. When he creates a small portion of arable land in adrought-parched land,he creates a battleground for the government and the rebels fighting against them. Neither side is right or wrong in the story - they're both brutal, but both fighting for something theybelieve in. Ostrander makes the nice point that in warfare, it's always the non-combatants who suffer the most.The situation in East Africa (the story doesn't take place in Ethiopia, but it might as well) and throughout the worldis not something that a superhero can solve simply by turning the land green. The nun who works with theUNrelief team, Sister Agnes, explains that the problems are too deep for surface solutions. Firestorm can't do everything that is necessary, so any little thing he does will make the situation worse.

This conundrum comes up again in thelatter half of the book. We have seen how Maya explains to Firestorm that humans are part of her, and to destroy them is not an option. Naiad, the Water Elemental, disagrees, as she is newly createdin a violent explosion like the ones that created Swamp Thing andFirestorm. She was once an activist named Mai Miyazaki, and she was killed by a representative of an oil company. She wants her revenge on Japan (the oil company isJapanese) and onhumanity in general. Later, Firestorm gets involved in a story with African gods, one ofwhom comes to Earth to find his long-lost brother.The god, Shango, believes that people areinsignificant gnats,but his brother, who is in a human guise, tries toteach him humility and the necessity of doing grass-roots work to make humanity better. This idea, that governments are inherently corrupt and it's good people working hard who will make a difference, is at the heart of Ostrander's run on the title. Mikhail Arkadin is a normal man, not muchdifferent than Ron. He wants to provide for his wife and children, but the Soviet government keeps interfering. Similarly, Jama, briefly the third member of Firestorm's matrix in issues #78-79, wants simply to provide for his family because his wife is dead. Tragically, he gets caught up in thecivil war in Ogaden (the East African country that is a stand-in for Ethiopia) and his dreams are crushed. Ostrander never allows his characters to lose hope, however, because heshows us how one man can make adifference. His politicalideas about how we can change the worldand the quest for identity dovetail in the final issue, in which Martin Stein sacrifices himself so that the world can be saved. Martin is one man, but he makes a difference. After the explosion that created Firestorm from Ron and Mikhail, Martin lost his memory. He never regains it completely, but the final story shows him regaining his identity as a hero. While the flawed Firestorm could never really change the world, Martin and the perfected Firestorm save it. It's a nice contrast.

As I've mentioned, the reason Firestorm isn't as well-received as Ostrander's other comics is perhaps because of the art. Brozowski, who pencilled the book for 21 issues during the run, is an unspectacular draftsman. Interestingly enough, in three issues (#67, 69, and 70), he drew under the name of "J. J. Birch" because he was experimenting with a new style. The issues in the 70s show a great deal of improvement from the earlier ones, but he nevermakes the book quite as majestic as it needs to be. Grindberg, who drew six issues, did a much better job, but the bookstill didn't look like itshould haveuntil Mandrake came on board. Mandrake, who teamed with Ostrander on GrimJack and would later work with him on The Spectre and MartianManhunter, is a very good artist, and he works very well with this kind of book. Like the Spectre, the character is larger than life, and Mandrake does a wonderful jobeschwing panel restrictions and giving us full-page spreads and magnificent battles between giants. Mandrake is good enough on the smaller-scale portions of the book, but it's when Firestorm battles Naiad, Shango, and Brimstone that he really shines. Ostrander was leaving the book anyway, so perhaps had Mandrake been on the book longer it wouldn't have helped, but it would have been interesting to see it throughout. Ostrander's story for the first 25 issues or so is very compelling because it focuses more on the politics, but once Mandrake comes on board, it feels as if he allows himself to cut loose a bit more.

Ostrander was working on Suicide Squad at the same time he was writing Firestorm, and although the former is better, that doesn't mean this isn't worthy. Working within a framework provided by DC and those who had come before him, Ostrander created a comic that probed international politics, environmental disaster, what makes us sentient, and the consequences of rash actions. Those who say he ripped of Alan Moore and the subsequent creators of Swamp Thing miss the point, because it's not the story you tell, it's how you tell it, and Ostrander, using the template provided by Moore,took Firestorm in a different direction, one that is compelling in its own right. Ostrander understands that characters that change may not gain a wider audience (the vagaries of the market being what they are), but characters that grow and learn and live become the foundations of classic stories. Ultimately, Firestorm failed in the short term. Perhaps there was too much change. DC has brought back the ugly costume and rebooted the character (even though I don't know the particulars, nor do I wish to), but this story remains as a testament to a writer who knows what he's doing and how to blend action with philosophy. It hasn't been collected in a trade, but the issues themselves aren't much more than cover price (between $1-$1.50). It's certainly a good comic to seek out the next time you're digging through the back issues.

By the way, I've updated the archive of all of these posts, in case you're interested.