With Black History Month here, a piece by Joseph Hughes on the `lack of black writers at Marvel and DC Comics has received justifiable attention. It's an issue that deserves as serious a consideration as the recent arguments for female creators, and it's something that can really be applied to every minority. Diversity strengthens comics: It brings new voices, new ideas, new perspectives. And seeing that ethnic and cultural diversity reflected within the fictional universes of superhero comics can be life-changing.

I grew up white in Whitesville, an insular community in a small northeastern Massachusetts town. I didn't know a single non-white person until I went to a new school in fourth grade -- and then I knew one non-white person. I still remember the bullying he received; I'd never seen it in real life. My first day there, during gym class, I thought they must be kidding but they weren't. I don't remember any teachers ever standing up against it. Sure, they would chastise the general rowdiness but not the racially-specific name calling he got. And when the poor kid would finally lash out, flailing within a sea of ugliness, he would be swiftly escorted out of the classroom. Class would resume without him, pretending his outburst wasn't the most emotionally honest reaction one could have in that kind of environment. He was written up, sent home, I'm not sure. I was the shy new kid, I had no idea how to respond to it. By junior high, he had vanished. For about the first decade and a half of my life, that was my real-world experience with "diversity."

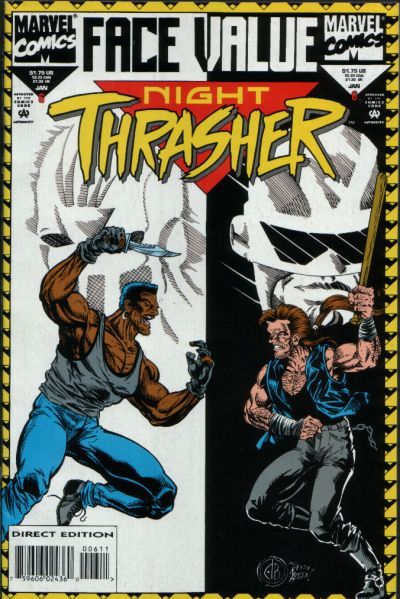

At some point I started reading comic books, and eventually made my way to superhero comics. The first superhero comic that I felt was my comic was Marvel's The New Warriors, which depicted a team of teenagers about my age or slightly older. They were formed and led by Night Thrasher, a black character with a mysterious past and no powers beyond his intelligence, fighting abilities and a tricked-out armored costume of his own design. Like that kid I knew, he would sometimes be overcome with frustration over the world around him and lash out, sometimes irrationally. But otherwise, he was a determined, disciplined, extremely resourceful young man who ran a company, invented things and ran a team of superheroes. The character resonated with me, but I wouldn't consciously draw a parallel between him and that former classmate for years. I just thought he was cool. They even managed to make the silly skateboard kind of cool. I liked him about as much as the rest of the New Warriors, which is to say quite a bit. They all treated each other like equals. They teased each other and butted heads like teenagers do, but it was never because of his skin color.

Really the issue of Night Thrasher's race hardly came up at all until his spinoff solo series. In the back of the first issue, writer Fabian Nicieza prodded readers by proclaiming the character "is not a black man, but he needs to learn how to be one." The implication seemed to be that his socio-economic background (raised by a black man and an Asian woman with the comforts of a wealthy inheritance) was not an authentically black experience. This provocative statement was thoroughly shot down in a lengthy letter from then-fan and future comics writer Kevin Grevioux in Night Thrasher #3, where he pointed out that Nicieza can have no idea what it's like to be a black man. "He may surmise, he may speculate, but he will have no intuitive insight," he wrote. And it's true. While I felt awful about what I saw happen to that kid, I can never know his full experiences. I can only imagine.

Three issues later, a story followed up on these ideas, and showed that while Nicieza's comment was ill-advised, his capacity to write stories about it could be effective. A riot breaks out between blacks, whites, Asians and Hispanics following a series of racially motivated attacks in New York City. As Night Thrasher breaks it up, someone challenges him for fighting against his "own kind." He shoots back, "My 'own kind'? What does that mean? We're 'brothers' because we're both black?" He goes on: "My kind are any kind -- black, white, yellow or blue -- as long as they obey the law and do what's right by others. Is that what these 'brothers' of yours and mine were going to do with bats in their hands and hate in their hearts?"

His stirring speech changes nothing, except someone throws a Molotov cocktail at him. The police arrive, someone opens fire, and Night Thrasher and his partner beat up everyone and force two of the rioters to confront each other one-on-one. They realize it's stupid, and everyone goes home, with maybe a few people thinking twice about what they'd done. Maybe. The issue ends with another racially motivated attack, and Night Thrasher again heads out to try to stop it.

This was unlike any "very special episode" I'd ever seen on television. Sure, the superhero bombast was there but so too was the harsh reality that haters gonna hate in a way that could end lives. The protest against violence was ineffective, the police were ineffective, superheroes were ineffective. And yet, at the end of the issue, either futility or hope prevails.

And so it is either futility or hope that Joseph Hughes, David Brothers and others again challenge the status quo, to ask for more black creators who might be able to teach and inspire by example like a fictional character did for me and no doubt others. Sometimes comics get it right with portraying diversity on the page but sometimes there are missteps, like Nicieza's comment. The more diversity there is behind the scenes, the higher the odds of getting it right, whether or not the stories are directly dealing with race and diversity. Because yes, just as Fabian Niceiza, an Argentinean-born white man can write effectively about a black man, so can black men and women write effectively about characters of different races and backgrounds.

The current pleas for greater diversity in comics are being met with silent resignation, justification, derision and more. But like in that Night Thrasher story, a few just might think twice about being against the idea.