Comics College is a monthly feature where we provide an introductory guide to some of the comics medium’s most important auteurs and offer our best educated suggestions on how to become familiar with their body of work.

This month we're going to take a look at the bibliography of the Canadian cartoonist called Gregory Gallant, better known to you and me as simply Seth.

Why he's important

Along with such cartoonists as Chris Ware and Chester Brown, and Joe Matt, Seth was one of the seminal cartoonists of the 1990s, building on the work started by 80s-era artists like the Hernandez brothers and Daniel Clowes, and helping to bring attention to the medium by telling literate, emotionally complex stores that resonated with a variety of adult audiences. The cultural success that comics eventually received over the past 10 years is due in large part to the hard work that Seth and his contemporaries put into the art form.

Because he works in a style that so deliberately harkens back to the classic gag cartoonists of the early 20th century, and because his stories are frequently set in the past, some critics have made the assumption that his work is all surface nostalgia, a simplistic longing for a idyllic past that never really existed. It's not. If anything, a closer reading of Seth's work reveals that he is deeply suspicious of that sort of bygone wistfulness. More to the point, his work instead reflects a concern with the passage of time and mortality, and how our lives and memories can often quickly be swept aside by successive generations. More than just a valentine to the early 20th century, Seth uses that period to ask questions about how culture and the times influence and shape us, and vice-versa.

Where to start

Of all of his books, I think Wimbledon Green makes perhaps the best entry point, as it is easily Seth's most lighthearted and whimsical work to date. What's more, in many ways it marks a demarcation part for the artist towards a looser, more organic style.

Though a lark, the book, which tells the story of a mysterious, legendary comic book collecter who lives in a world where such characters can afford to have manservants and gyrocopters in their pursuit of that elusive issue of Green Ghost #1, carries a strong, melancholy undercurrent that keeps it from becoming too much of a trifle, and ruminates on a number of the afore-mentioned themes that resonate throughout the author's oeuvre.

From there you should read

Continuing on the ground laid by Wimbledon Green, George Sprott offers a portrait of an elderly TV personality in a small Canadian city, as viewed from the perspective of various people who knew him at different times in his life. I reviewed the book for Robot 6 back in 2009 so I won't repeat myself too much here except to say that it remains Seth's strongest work to date.

Seth came to national attention (or whatever the alt-comix equivalent of that may be) in 1996 with the publication of his first graphic novel It's A Good Life If You Don't Weaken, a seemingly autobiographical (but really completely fictional) account of the author's attempts to learn about an obscure New Yorker cartoonist. The good news is time hasn't dimmed this book's quality much. It remains a rich, evocative work and the next, logical step for those who want to continue to reading more of his comics.

Further reading

Since 1997, Seth has been working on Clyde Fans, the story of two brothers with diametrically opposite personalities -- one outgoing and abrasive, the other meek and overly sensitive. Though still unfinished, the first half of the saga has been collected as Clyde Fans, Book One, and while it certainly remains an affecting work so far, you may be forgiven for thinking that you'd like to wait until the series is finished and collected under one cover.

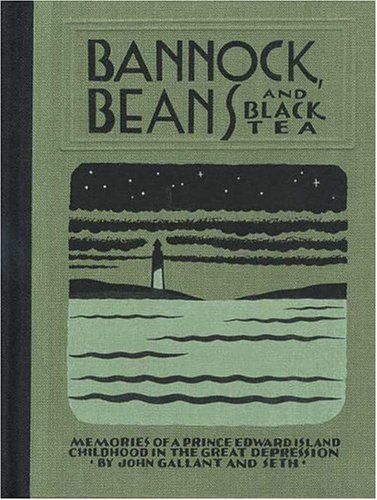

For about a decade, Seth collected various stories his father told him during his childhood about growing up in rural Canada during the Great Depression and collected, lettered and illustrated them in Bannock, Beans and Black Tea. Occasionally harrowing, sometimes heartbreaking, these stories portray a real, true, bitter poverty that hopefully few of us will ever know. While more straight prose than comics, it remains a haunting book, and should not be ignored simply because it is not sequential art.

Ancillary material

Those who have developed a special appreciation for Seth's unique art style should definitely check out Vernacular Drawings, a lovely coffee-table sized culling of the author's various sketchbooks.

Both Clyde Fans and It's a Good Life were initially (and in the case of Fans, continue to be) serialized in Seth's ongoing series, Palookaville. Never collected in a book, the first three issues are worth tracking down, especially since they show the artist trying his hand at (one assumes) autobiography. The first issue recounts a time where he was assaulted (and apparently had long white hair) while issues 2-3 reveals of how he lost his virginity to an older woman.

If you want to track down even earlier work, I recommend searching the back issue bins for early issues of the first edition Drawn and Quarterly Anthology (i.e., the thin, magazine format) where you'll find him attempting a number of short, one and tw0-page fictional stories. If you want to see him trying his hand at a more mainstream type of comic, check out the Mister X Archives, where he does the art chores for a few Dean Motter stories.

Seth's illustration work abounds, and can be found decorating a number of books, advertisements, CD packaging (Aimee Mann's Lost in Space being a notable example) and DVD covers. He's also had a second career of sorts as a book designer, most notably on the John Stanley Library and The Complete Peanuts series. Some critics have complained that Seth's style is so overpowering that it tends to overshadow the work of the artist that's supposedly the focus of the book. It's a valid criticism as far as it goes, but I tend to feel that it's something that only rarely occurs and that on average his art does a more effective job of celebrating the artist in question rather than shouting them down.

Seth has always been something of an armchair historian and critic as well, as his attempts to bring artists like Doug Wright back into the spotlight show. It's a role perhaps best examplified by the little chapbook, Forty Cartoon Books of Interest, which was bundled along with issue no. 8 of Comic Art magazine. It's a charming little tour through some of the author's most treasured books, most of which you've probably never heard of before. You can still find new copies of that issue of Comic Art -- chapbook included -- on the Internet.

Finally, while he's been interviewed a number of times, the best is probably the one he did with Gary Groth in The Comics Journal #193 (but good luck finding a copy).

Avoid

Last year saw Seth become yet one more alt-cartoonist to abandon the traditional pamphlet format with the release of Palookaville Vol. 20. Designed as an annual as a small book, not unlike recent volumes of Chris Ware's Acme Novelty Library, the new format ostensibly gives Seth the opportunity to include different types of stories, art and writing and take more chances (in addition to continuing Clyde Fans).

Unfortunately, vol. 20 comes up a little short -- the new chapter of Clyde Fans feels a bit to in media res even for those who've been following it all these years, and the concluding story, about a trip to Calgary, is the sort of self-loathing, solipsistic, navel-gazing nonsense that indie comics routinely and unfairly get flagged down for. It's certainly not a book to be avoided per se, and I'm have the utmost confidence that future volumes will show him knocking it out of the park once again, but this is definitely not the best place for newcomers to start their journey.

Next month: Frank Miller