Comics College is a monthly feature where we provide an introductory guide to some of the comics medium’s most important auteurs and offer our best educated suggestions on how to become familiar with their body of work.

Today we're looking at one of the comics medium's most restless and interesting inventors and theorists -- and a pretty compelling storyteller to boot -- Scott McCloud.

Why he's important

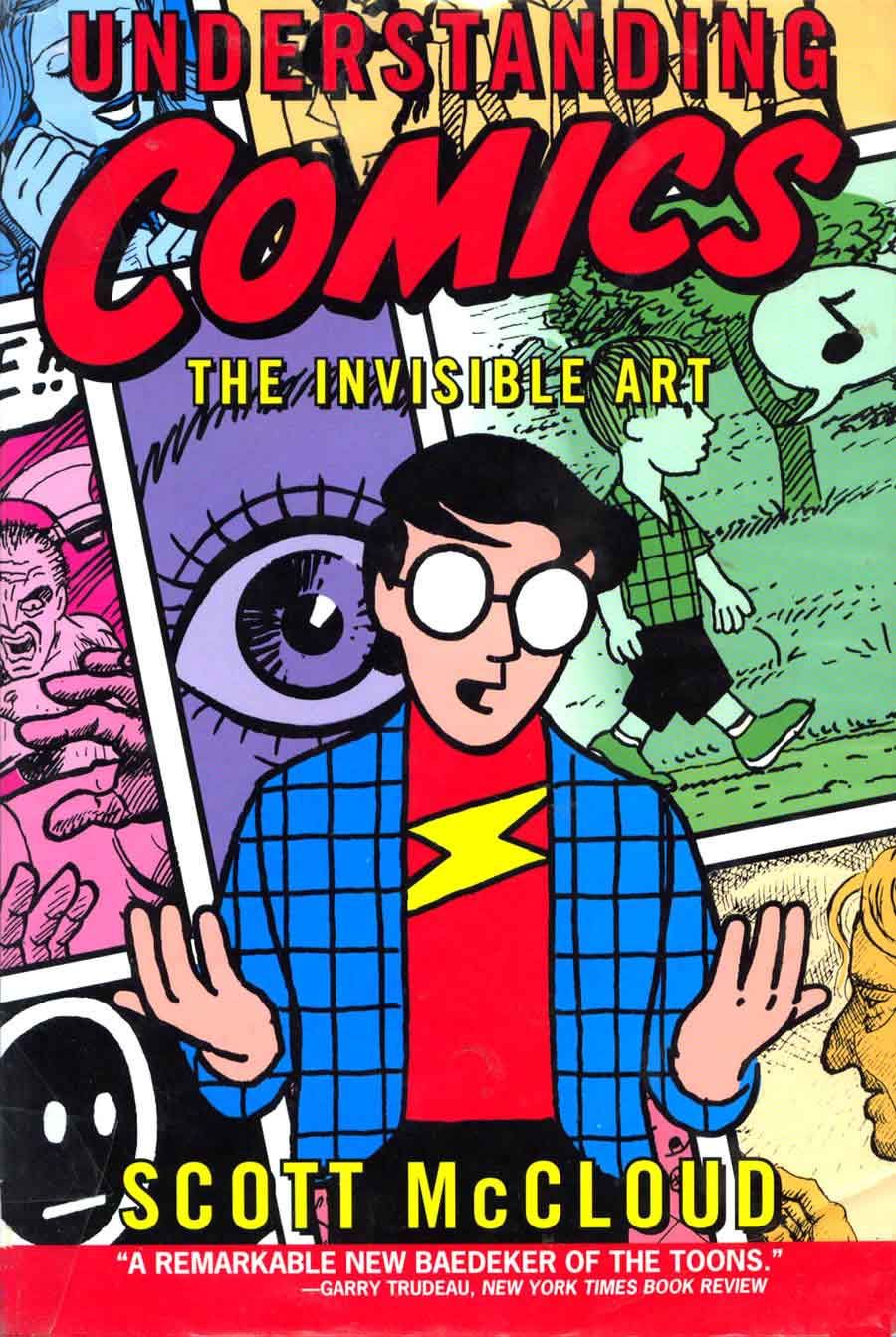

Even if he produced nothing else of worth in his career, Scott McCloud would still be hailed for Understanding Comics. Arguably one of the most influential graphic novels in the history of the medium (and certainly one of the most talked about books of 1990s), McCloud's in-depth treatise on what made comics so unique and cool was a revelation to both fans and cartoonists when Tundra published it in 1993. It was the first time any creator (at least any creator in North America) had made a serious attempt to study and explain the inner workings of their medium to a general readership. Despite the criticism that have risen in its wake, the effects of Understanding continue to be felt today.

Thankfully, McCloud is more than a one-trick pony. When not theorizing on the future of comics and the medium's potential, McCloud also has proved to be a gifted storyteller, most notably in Zot!, where he created a sharply realized and emotionally involving cast of characters. He's also proved to be a dedicated experimenter, constantly pushing at the limits of the form to see what it's capable of.

Where to start

Why even quibble about it? The best place to begin is with McCloud's best-known work, Understanding Comics. While numerous criticisms have arisen regarding certain aspects of the book -- his loose definition of art, his even more frequently contested definition of "sequential art" -- it remains as thoroughly engaging and thoughtful as it was upon its initial release. Almost 20 years later, there's still no other book quite like it.

From there you should read

Hold off on Reinventing Comics for now and instead skip ahead to Making Comics, McCloud's lengthy guide on how to move from the theoretical side to the production side of things Rather than a simple "how to draw" book, McCloud guides the reader through the various essential aspects of comics storytelling, from imbuing your characters with personality, to setting your story in a believable world to learning how to time your stories effectively. Alongside with Drawing Words, Writing Pictures, it's one of the best guide books for would-be cartoonists and should be an essential part of any aspiring artist's library.

McCloud's first foray into comics was Zot!, a sci-fi/fantasy/superhero series about a world-weary teen Jenny, who inadvertently travels to a futuristic parallel world complete with an effervescent and perpetually chipper teen hero. Although the first 10 issues of the series are out of print (see below), the rest of the series was collected a few years ago by HarperCollins as Zot!: The Complete Black and White Edition. This is some of McCloud's most moving and captivating work, especially in the second half of the book as he clearly gets weary of the superhero shenanigans and transports Zot back to the "real" world and starts focusing on Jenny's circle of friends. If you only know McCloud through his nonfiction work, then you owe it to yourself to read this book.

Further reading

After finishing Zot's initial 10-issue run, McCloud produced Destroy, a jumbo-sized superhero parody that is little more than two costumed doofuses slugging it out for 32 pages. Completely over the top in the best manner and chock-full of senseless violence (indeed, New York City is reduced to little more than rubble), Destroy is a complete hoot. It's out of print but you can find copies here and there online and in comic shops.

The only item McCloud doesn't include on his online bibliography is Five Little Comics, a bite-sized package of five mini-comics that Wow Cool put out not too long after Understanding took off. It's minor work to be sure: One comic consists of expressionist faces done in charcoal. But it's nevertheless a fun bunch of comics, not to mention a chance to see McCloud's more carefree, experimental side, especially in the abstract Birth of a Nation (although my favorite is Some Words Albert Likes).

Then there's Reinventing Comics, McCloud's "sequel" to Understanding. Divided into two sections, the first half of the book discusses the medium's artistic potential, the failure of the community at large to perceive comics as an art form, and how the business end of things hinders genuine artistry. The second and more controversial half examines the potential freedom comics can have on the Internet (i.e. the "infinite canvas") and how micropayments offer a new, more feasible method for cartoonists to make a living. Frankly, this is not a book time has been kind to. The graphic novel boom of the last ten years has made McCloud's comments about media perception and the industry's lack of breadth seem dated (though he sadly remains completely relevant where issues of creator's rights are concerned). And the rise of programs like Kickstarter, to say nothing of the success of webcomics like Penny Arcade and xkcd question the need for the micropayment system as well as readers desire for the sort of "infinite canvas" McCloud trumpets. All that being said, it's still an interesting and worthwhile read, particularly if you have an interest in how comics take advantage of new technology.

As an early and strong adopter of the Internet, McCloud has produced a variety of webcomics, most of which are available for free on his web site. My personal favorite is My Obsession With Chess, which is about as self-explanatory a title as you're ever going to get. Also worthwhile is the currently unfinished, The Right Number, a story of a man's obsession with finding the perfect mate. There's also Hearts & Minds, a fun, if ancillary Zot story; The Morning Improv, a series of unrelated comics allegedly thought up on the spot; and I Can't Stop Thinking, an appendix of sorts to Reinventing Comics.

Ancillary materials

When not working on his own comics, McCloud has done work for hire projects for some of the more mainstream publishers, usually DC and usually Superman. He wrote about 12 issues of Superman Adventures, the sleek spinoff of the '90s animated series. The first six issues of those were collected in trade paperback and are pretty easy to track down. He also wrote Superman: Strength, a three-issue prestige miniseries that hasn't been collected but again isn't too tough to find. Both are enjoyable, if slight, superhero tales that will best be enjoyed by serious Kal-El devotees.

One of McCloud's more recent work-for-hire jobs was the Google Chrome comic, an introductory guide to the company's hot new web browser that goes to great length to explain why it's so awesome. Certainly if nothing else it proves why any company, tech or otherwise, would be smart to hire McCloud to create their marketing material.

The new Zot! book doesn't collect the first 10 issues, which were printed in color. For his part McCloud doesn't seem too thrilled with his earliest work ("it has its moments"). Kitchen Sink Press did collect those issues into a trade book several years ago before the company went out of business, but copies are selling at premium prices and I had difficulty locating an affordable copy. You might have better luck however.

Among his many inventions, McCloud -- along with Steve Bissette -- came up with the idea of the 24-hour comic, which is exactly what it sounds like, a comic produced in a 24-hour period. You can see his first attempt, A Day's Work, at his website. He also edited the 24-Hour Comics anthology, which contains work by folks like David Lasky and Matt Madden.

Avoid

McCloud's most immediate follow-up to Understanding Comics was The New Adventures of Abraham Lincoln, a fanciful treatise on American history that involved space aliens, Benedict Arnold and the 16th president. As my meager description suggests, the plot's a bit of a muddle and McCloud's initial attempt at using computer-generated artwork only compounds the problem. His combination of 2D characters and 3D backgrounds is especially garish. That's not to say there aren't some moments -- there's a Jim Woodring-esque sequence in the middle that's almost worth the price of entry -- but it's not the first place for newcomers to begin.

Next month: Charles Burns