Welcome to a new feature we're starting here at Robot 6 titled "Comics College." Once a month (or more if time permits) we'll be examining the body of work of a particular cartoonist or cartoonists of note in the hopes of giving newcomers and the generally uninitiated an entry point. Because let's face it, there are a number of notable creators who have had lengthy careers in comics and figuring out where to start when reading their ouevre can be tricky, especially if not all of their material is easily available in print.

"Comics College" was inspired largely by the AV Club's Gateway to Geekery and Primer features. More specifically, it was inspired by their attempt to provide a overview of Gilbert ("Beto"), Jaime and Mario Hernandez's Love and Rockets series. I found I disagreed with a number of the suggestions and points they made, enough so that I decided I needed to do my own version.

Which is why we're beginning our debut post with a look at the Hernandez brothers. A lot of readers out there are wary about trying to dip their toe in the Love and Rockets waters and it's not surprising. The series has been going on for decades now in a variety of series and formats. Their reputation for telling long involved stories, can seem overwhelming and scary for those unsure where to begin.

So, come, take my hand and let me be your guide ...

Why they're important

In the early 1980s, Love and Rockets was one of the seminal titles, along with books like Cerebus and American Flagg, in shaping the sensibilities of the nascent indie scene. Their influence since then has been enormous, both in the indie world and the mainstream (writer Matt Fraction cites Gilbert Hernandez as a strong influence). Their jump-cut style, which forces the reader to connect the narrative dots beetween the panels, their blend of genres (science fiction, realism, romance), their use of magical realism all helped show that not only could comic be serious literature, but how to achieve such a goal.

Beyond that though, both Gilbert and Jaime are incredibly gifted storytellers -- giants in the field really -- able to create emotionally powerful, complex tales populated with unique but relatable characters. By this point, they've easily earned seats in the upper pantheon, next to folks like Carl Barks and Will Eisner.

What's more, they're really good at drawing purty girls.

Where to start

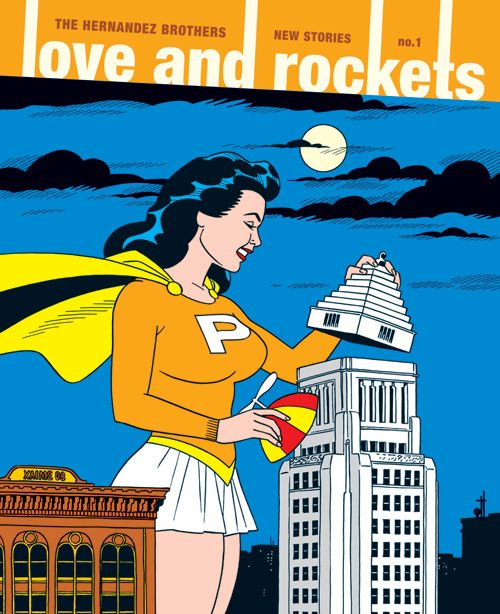

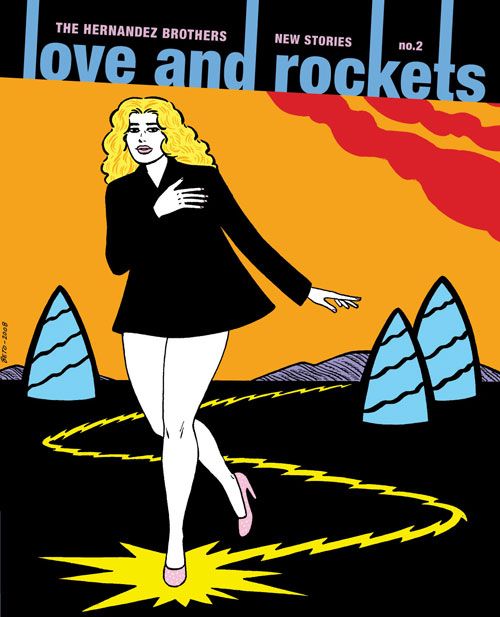

This is actually the best time to try to dive into L&R waters, as they just revamped their flagship series into an annual booklet, entitled Love and Rockets: New Stories, and both have abandoned their usual modis operandi to try their hand at some new stories aimed at drawing in new readers.

Jaime's Ti-Girls Adventures, for instance, is a bona fide superhero story, done with a verve, intelligence and sensitivity that rarely ever seen in any of the Big Two's comics.

Gilbert, meanwhile, is using the new format to experiment via a variety of surreal, standalone tales. Papa, for example, is the story of a man attempting a long trip on foot who comes down with a strange disease. The bizarre, violent aspects of some of these stories might put some readers off, but they do a good job of showing his range and complexity. Thus, I tink issue No. 1 of New Tales is a very good way to dip your toe into Los Bros waters.

But some of you will want to start at the very beginning no doubt. In that case I would strongly recommend picking up the Love and Rockets Library series of squarebound, $15 books, which collects the brothers' initial run into three, distinct volumes each. They're affordable and a surprising improvement on the previous slim, larger volumes.

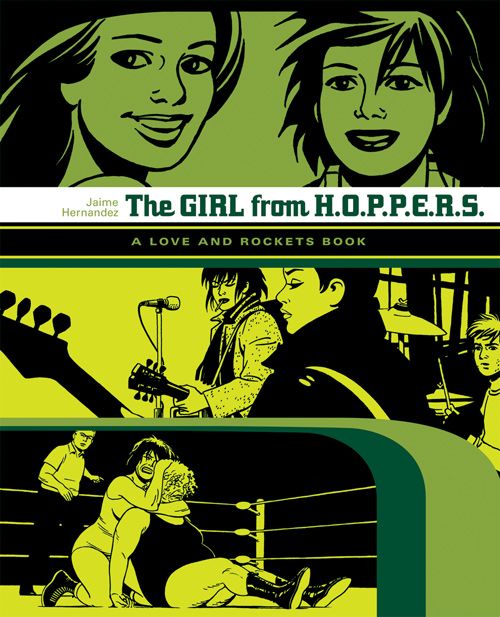

But which one to buy first? Let's start with Jaime, who is best known for his Locas saga, a sprawling series of interconnected stories mainly focusing on two female friends/sometime lovers named Hopey and Maggie, who live in a Hispanic suburb somewhere around Los Angeles and their collection of friends and acquaintances. The stories follow their awkward, earnest relationship amidst the burgeoning punk rock scene, gang troubles and more.

I wouldn't, however, begin with the first volume, Maggie the Mechanic. These initial Maggie and Hopey stories have a decidedly awkward sci-fi touch, with Maggie working as a rocket ship mechanic and traveling to islands filled with dinosaurs and revolutionaries and whatnot. While it's entertaining, Jamie abandoned most of that material later on and the stories do not gel well with his later work. What's more, Jamie's art feels a lot rougher and sketchier here, as though he's still trying to find his voice, compared to the graceful elegance he would exhibit later on.

Instead I'd suggest new readers go right to the second volume, The Girl from H.O.P.P.E.R.S. which contains the Death of Speedy story, which was one of the seminal moments in Jaime's development as an artist and storyteller. From there you can go back to Maggie and then forward to Perla La Loca, which finds the pair trying to recapture their carefree early days with little luck.

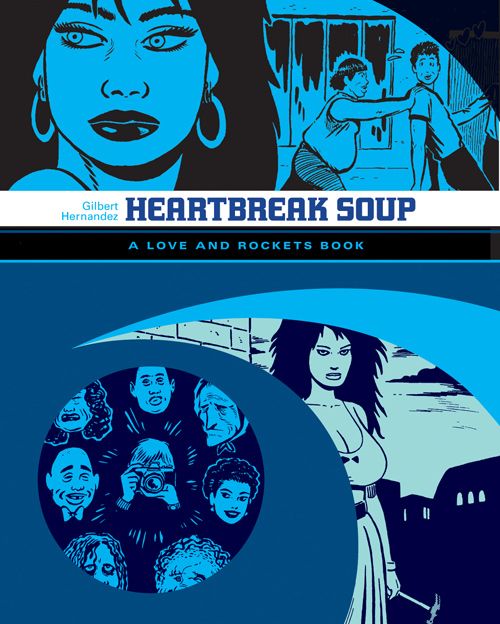

Gilbert spent most of the '80s focusing on a small, rural village in Mexico called Palomar, ruled by a no-nonsense but alluring (and large-bosomed) mayor named Luba, who is rarely seen without her large brood of children or the hammer she always carries in her hand. New readers should feel free to start right in on Heartbreak Soup, progressing from there to Human Diastrophism and Beyond Palomar, which covers Luba's early history in Poison River.

From there you should read

In the 90s the brothers decided to end Love and Rockets and went off to try their ownm, individual series before joining again to start a second L&R series, though this time in the more traditional comic book format. Most of these tales have been collected in trade and that's the preferable option rather than trying to hunt down back issues.

From here the Locas saga continues in this order: Locas in Love, Dicks and Deedees, Ghost of Hoppers and The Education of Hopey Glass. The last two rank among Jaime's best work to date, with a now middle-aged Maggie and Hopey having to re-evaluate their lives. You don't need to read all four in order to enjoy them, but it will help solve any minor narrative confusion.

Gilbert, meanwhile, moved Luba to America and chronicled her family's adventures in the following books: Luba in America, The Book of Ofelia and Three Daughters. These I do strongly recommend reading in order, as there's a specific narrative drive that climaxes in the third volume. Gilbert also went back in time for Fantagraphics' Ignatz series with the three-issue New Tales of Old Palomar. This hasn't been collected yet, but the individual issues aren't tough to find.

Ancillary material

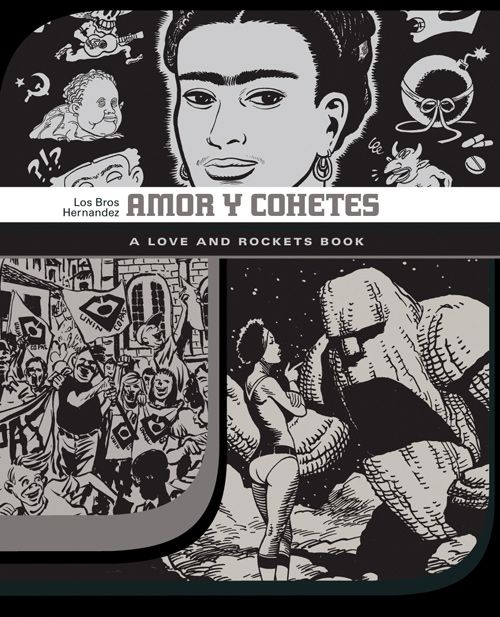

It's a horrible analogy and I apologize in advance for it, but the Zeppo Marx of the family is Mario Hernandez, who, though he was allegedly the inspiration for them to make their own comics, only occasionally contributes to the L&R books (though he's currently working with Gilbert on Dark Horse's Citizen Rex) His stuff is collected in Amor Y Cohetes, a catch-all collection of short pieces that don't relate to the Locas or Palomar stories. There's some really good stuff in here, particularly some of Gilbert's biography of painter Frida Kahlo, but it's far from an essential purchase.

Apart from the occasional illustration, Jaimie hasn't branched out too far from his Locas stories, the sole exception being the female wrestling saga Whoa Nellie. It's a cute little comic but it's definitely one of his less significant works.

Gilbert, however, is an incredibly prolific and downright restless cartoonist and the list of his non-L&R work is truly staggering. In short, Birdland, Fear of Comics, Girl Crazy, Grip the Strange World of Men, Sloth, Chance in Hell, Speak of the Devil, and the upcoming The Troublemakers. And I haven't even talked about the collaborative stuff he's done with folks like Peter Bagge. Birdland's fun if you don't mind hardcore pornography. Fear of Comics is a good way to sample his more experimental stories. As for the rest, I'd recommend Sloth, Chance and Speak as some of his best non-Palomar work, though really it's all good.

Avoid

The big coffee-table presentations of their work -- Luba, Palomar, Locas I and Locas II. They're expensive, really, really big, are missing some seminal stuff like Jamie's Flies on the Ceiling and just in general aren't the best way to experience the brothers' work.

Next month: Jack Kirby