Comics College is a monthly feature where we provide an introductory guide to some of the comics medium's most important auteurs and offer our best educated suggestions on how to become familiar with their body of work.

Today we'll be crossing the Atlantic to take a look at the one of the most prolific cartoonists of the past 30 years, either in Europe or America, Lewis Trondheim.

Why he's important

Beyond being one of the most celebrated names in French comics, Trondheim was one of the stars -- perhaps in some ways the biggest star -- of the small press movement in Europe in the 1990s that gave birth to artists like David B, Marjane Satrapi, Joann Sfar and Chris Blain (indeed, as one of the founding members of the seminal publishing group L'Association, you could argue that he helped give birth to the movement in more ways than one). As Bart Beaty so aptly puts it in his book, Unpopular Culture:

That an artist who, by his own admission, had no ability to draw could become one of the most prolific, popular and financially successful cartoonists of his generation was conceivable only given the redefinition of the field by the artists of the small press. Few cartoonists involved in the movement have yet matched his success, and his victories are not entirely shared. However, the ascension of Trondheim to the top ranks of European cartoonists and his ongoing success in a number of related fields and international markets symbolize the importance of the entire small press revolution and the transformation of the comic book field that it put into motion.

What's more, having produced over 30 books in as little as 10 years, he straddles genres -- be it humor, autobiography, adventure, fantasy, children's books, historical fiction or experimental works -- with uncanny ease. American cartoonists looking to try a similar trick should look to his example.

Where to start

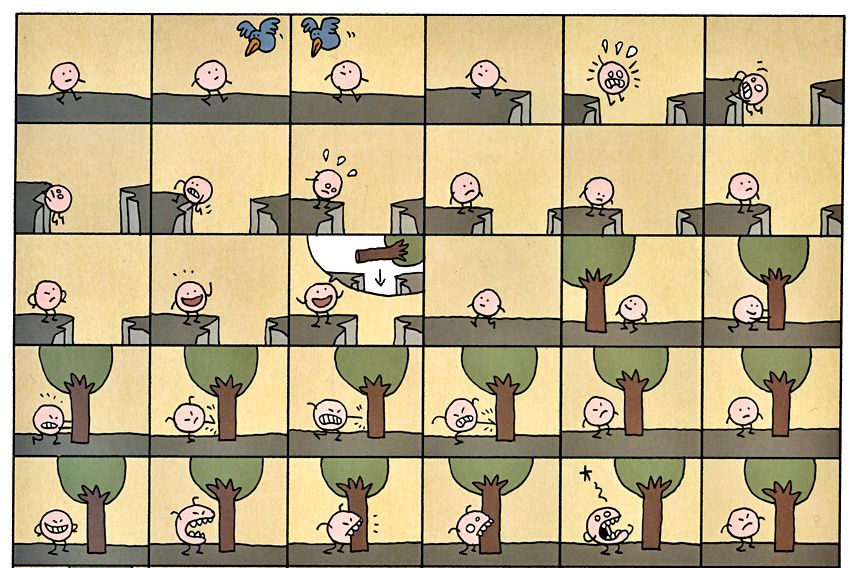

The best place to begin is Mister O and Mister I, both easily available from NBM. These two thematically similar, deceptively simple books (O concerns a round-shaped creature who keeps attempting to traverse a short gorge and fails; I deals with an elongated man who tries to find food only to meet one gruesome death after another) provide a good sense of Trondheim's black, dry wit, his love of formal play, his excellent sense of timing and his ability to convey action and emotion in just a few lines. They're both very emblematic of his general attitude and style and both very funny.

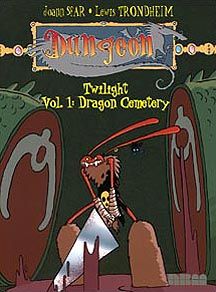

Another good place to start is the Dungeon series, a ongoing, epic fantasy series he's currently working on (and will probably never finish) with Sfar and a revolving door of artists. The series started out as a spoof of your average D&D-type stuff but has ended up taking on a life of its own, spanning out to cover hundreds of years, many characters and many, many volumes. You should start with the first one though, Duck Heart, also from NBM. (In general, I'd recommend reading the series in this order: Zenith, which covers the "present day;" then Twilight, which looks into the future; then The Early Years; Parade, which is unrelated, fun stories; and Monstres, which focuses on the supporting cast.)

From there you should read

Once you finish (or at least get through most of) the Dungeon books, move on to the Little Nothings series, a collection of one-page autobiographical strips (originally serialized on Trondheim's website) in which the author provides a humorous, off-the-cuff look at his general philosophy and day-to-day existence. The series is up to three volumes here in America -- The Curse of the Umbrella, The Prisoner Syndrome and Uneasy Happiness -- and they're all good.

In the late 1990s, Fantagraphics took a stab at introducing Trondheim to an American audience. The books sold poorly (to put it mildly), but both Harum Scarum and The Hoodoodad remain supremely entertaining tales featuring McConey, Trondheim's shy, nonplussed, anthropomorphic rabbit and his friends.

Not to let one bad attempt keep them down, Fantagraphics tried again with an ongoing pamphlet series, The Nimrod, which sadly only lasted seven issues. It's a great hodge-podge of some classic Trondheim material though, including autobio stories, McConey tales and the great wordless piece, Diablotus (found in issue #2). The back issues are available at dirt cheap prices too.

For a look at Trondheim at his blackest and most grotesque, pick up A.L.I.E.E.E.N, a dark, disturbing, but frequently hilarious (and again, wordless) tale of life on an alien planet that literally ends with everything drowning in a flood of excrement.

Further reading

In addition to producing his own comics, Trondheim has collaborated with a number of noteworthy European artists, most notably on the Dungeon series, but also on a number of kids' comics.

My favorite of the bunch is Tiny Tyrant, done with Fabrice Parme, which chronicles the hilarious adventures of a monomaniacal boy king. Also good is Astronauts of the Future, featuring art by Manu Larcenet and centering on a precocious boy and girl who are convinced that there's an alien conspiracy afoot in their sleepy town and discover that it's completely true, but not in the manner they initially thought.

Trondheim initially began Kaput and Zosky, the comical adventures of two would-be space warmongers who can't conquer a planet to save their lives, on his own but then let Eric Cartier take over the art chores, with somewhat lesser results. Still, it's a pretty funny series, goofy enough that your kids will get a kick out of it (and successful enough to warrant an animated series, episodes of which you can find on YouTube).

Finally, for the very young reader there's the Li'l Santa books he did with Thierry Robin. These cute, wordless (it's a running thing with Trondheim) tales feature the manic adventures of a pint-sized Santa Claus. NBM has released two of them so far.

Ancillary material

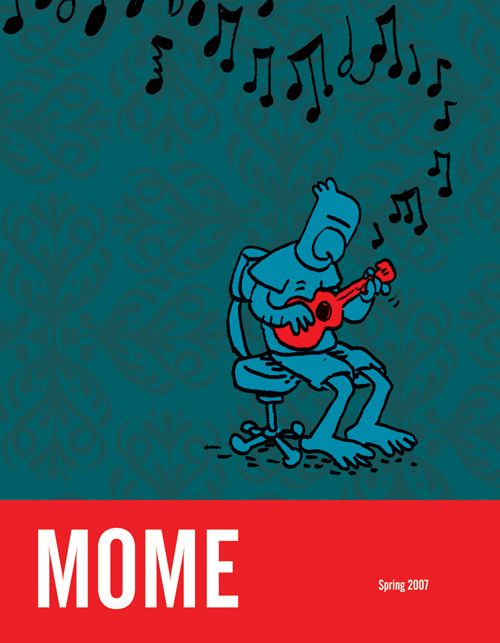

In 2004, Trondheim announced his intention to retire from comics (it didn't last long) a decision he chronicled in At Loose Ends, a sprawling, thoughtful examination of the creative process, how age can dull the imagination and the thin line between art and commerce. Fantagraphics serialized it in three issues of their Mome anthology (vol. 6-8 to be exact).

If you don't mind doing a bit of digging around the Internet, and you're willing to pay a bit more for shipping, I'd recommend checking out some of the artist's as-yet untranslated works. There are a number of "silent" comics that have yet to be published stateside, like Non, Non, Non or the fantastic La Mouche. The latter is the story of a fly who for reasons best not spoils, finds himself growing to monstrous size. It's a fabulous comic that, if it were more easily available in the U.S. I would have included it up in the "start" section at the top of this post.

If you want to learn even more about Trondheim, I recommend picking up a copy of issue no. 283 of The Comics Journal, which features an extensive interview with him.

Avoid

I enjoyed Bourbon Island 1730 (co-written with Appollo), but it didn't tickle many people's fancy. I can sort of understand why. It's a departure from what most American readers have come to expect from the artist -- much more serious, downbeat and contemplative than the concept (Trondheim does pirates) than you'd expect, and the detailed but loose and sketchy black and white sketch art came off as cluttered and difficult to read. I don't agree, but I can see where it might not be the best place for a neophyte to begin. Make it your last stop on the Trondheim express.