Comics College is a monthly feature where we provide an introductory guide to some of the comics medium’s most important auteurs and offer our best educated suggestions on how to become familiar with their body of work.

Welcome and happy holidays to all our Comics College readers. Today, as a post-Thanksgiving treat to you, we'll be talking a lengthy look at the career of one Georges Remi, better known by his pen name, Herge, and by extension, his most famous creation, the plucky boy reporter Tintin.

Why he's important

There are only a handful of cartoonists in the world who have had as enormous and significant an influence in comics as Herge has. There's Osamu Tezuka, Charles Schulz, Jack Kirby and then there's Herge. The incredible popularity of the Tintin books and their considerable influence on European comics really cannot be overestimated. Artists like Joost Swarte and Yves Challand built their entire careers upon Herge's style, creating what eventually would be known as the "ligne claire" school. Herge to Eurocomics is sort of like the Beatles to rock music: You're either influence by it, or you work in opposition to it. There's no in between.

Plus, Herge's work remains utterly charming and enthralling after all these decades. Though ostensibly created for younger readers, the Tintin books are some of the few all-ages books that can be read by adults and children alike, without any embarrassment on the former's part (well, there are one or two exceptions, but we'll get to that later).

Where to start

Though he did create other characters, Herge is primarily known for Tintin, the crime-solving reporter (even though he mysteriously never files a story) who, with his cadre of friends and little dog Snowy, brings down a rabble of drug pushers, spies, counterfeiters, dictators, warmongers and general bad guys.

Tintin's American publisher, Little, Brown, has, in recent years, made the decision to package three Tintin stories together in one, much smaller, hardbound volume apiece. It's not a move I support, quite frankly, as I feel it doesn't give the reader the chance to fully appreciate Herge's detailed, precise art in the manner it was initially designed for. Instead, I'd suggest picking up the individual, traditional BD-sized books, most of which are still easily available online. The hardcover volumes are admittedly a cheaper option in the long run though.

Having disparaged the hardcover volumes, I will admit that the Collector's Gift Set, which collects all of Tintin's color adventures (minus Tintin in the Congo, more on that in a while) is pretty spiffy looking. Still, at $150 a pop, it's might not be the first purchase a Tintin neophyte might want to make.

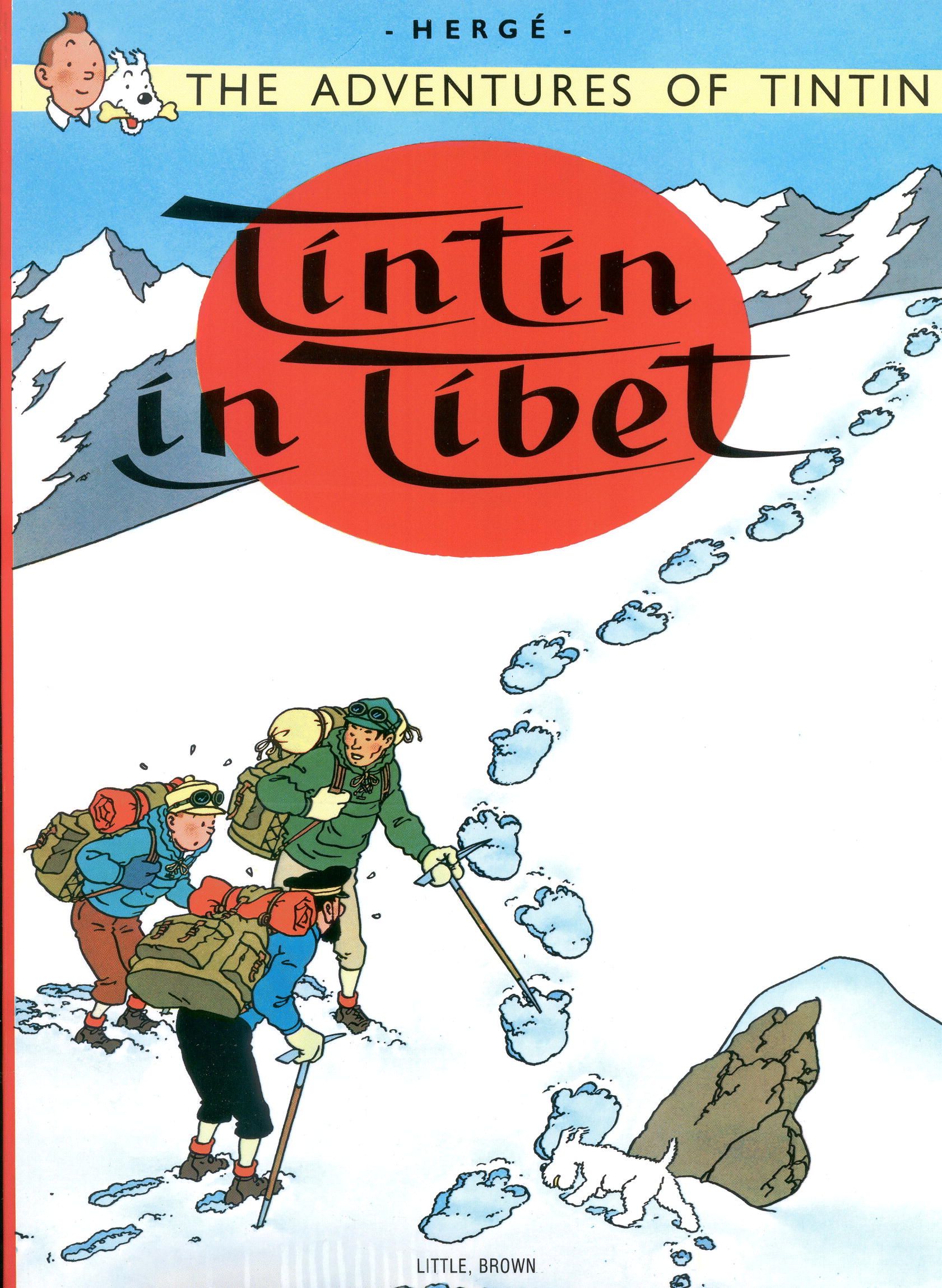

So, all that being said, if you're going to stick with the hardbound volumes and you don't want to blow your whole wad on the complete set, then I recommend starting with Volume six, which contains what most Tintinologists consider Herge's finest moment, the lovely Tintin in Tibet, in which our hero treks to the Asian land in search of a friend he believes has survived a horrible plane crash, even though all evidence points to the contrary. It's a touching tale about sacrifice, faith and friendship and shows the amount of research and detail the author put into his books. You'll swear after reading he actually visited the country even though he never did.

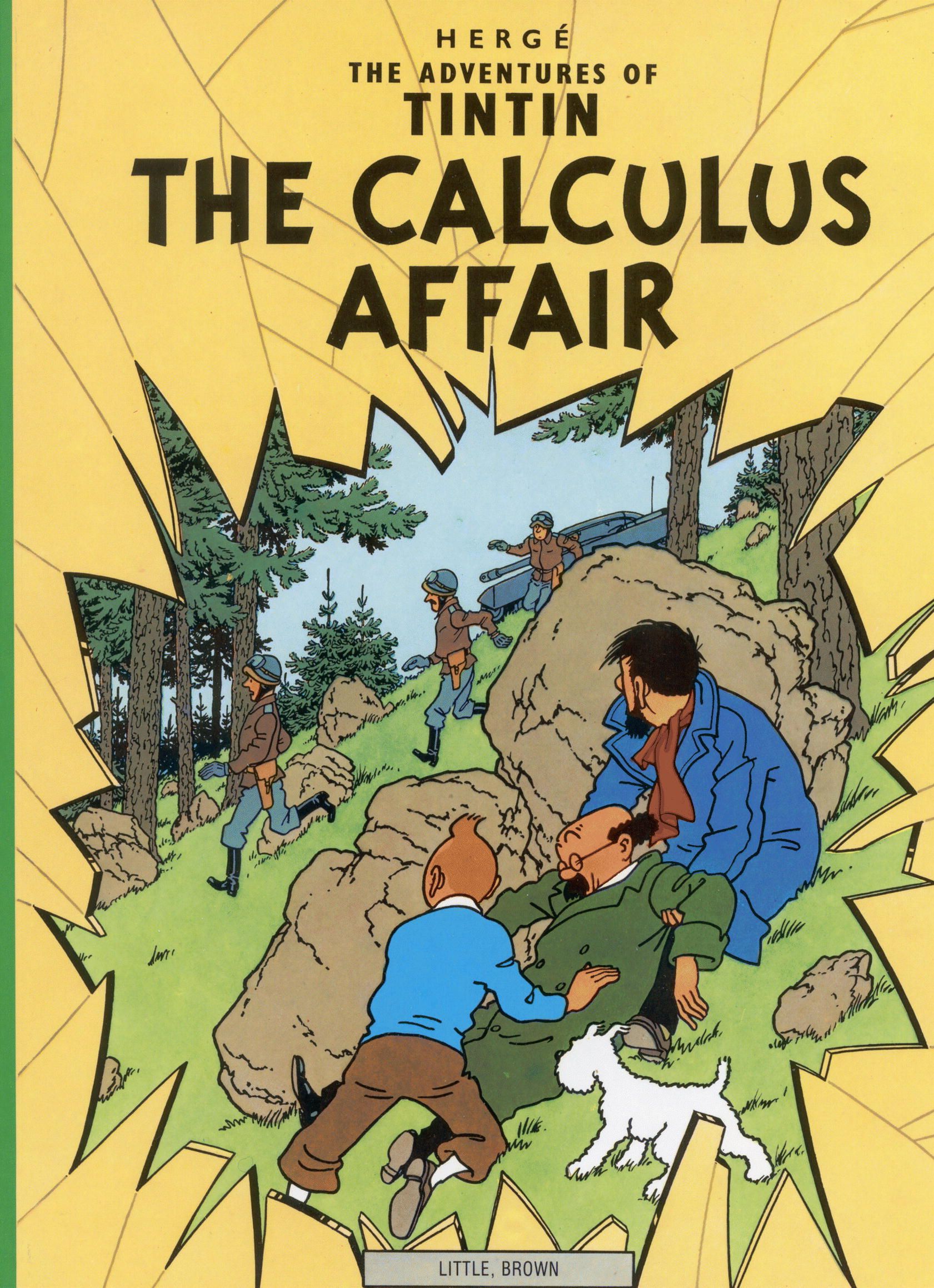

Volume 6 is also recommended as it contains The Calculus Affair, one of my personal favorite stories and, I think, a rather archetypical tale, and also quite good Red Sea Sharks.

From there you should read

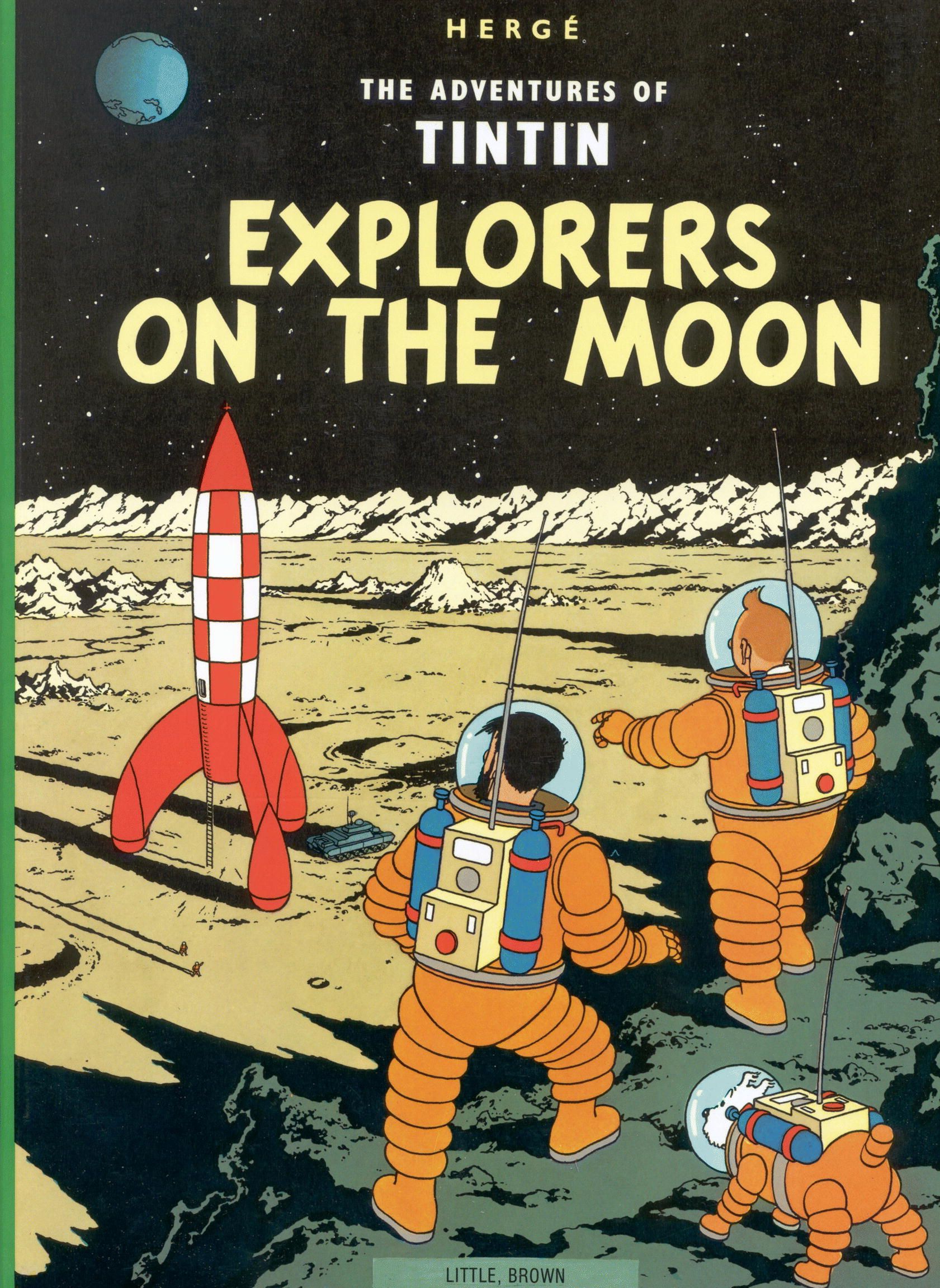

Volumes three, four and five contain some of the best and most memorable Tintin tales, including the two-part Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham's Treasure (in which Tintin searches for buried treasure and we meet the deaf genius Prof. Calculus); the Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun (in which Tintin heads to South America and meets up with some ancient Incans); and the excellent Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon (which contains some rather accurate predictions about space travel). These books are about as good as Herge ever gets.

From there I'd go back to the earlier volumes one and two, which feature Tintin minus his usual boozing companion Captain Haddock (and, in several cases, before Herge became more culturally aware and devoted himself to researching the places he wrote about). Of special note here are The Blue Lotus, which marks a turning point in the artist's attitude towards other cultures and the world around him. Also good are The Cigars of the Pharaoh, Lotus' prequel, The Black Island, which finds him in Scotland, and King Ottokar's Scepter, a great bit of escapist fun involving an attempted coup d'etat in Eastern Europe.

Conclude your Tintin reading with the final volume, number seven, which contains the Castafiore Emerald, Flight 714 and Tintin and the Picaros. The latter two verge dangerously close to self-parody and you get a sense Herge was growing tired of the formula and perhaps even feeling a little trapped by his creation. Emerald, however, is a great little drawing room comedy, with Tintin staying at home for once.

Further reading

Herge was working on Tintin's 24th adventure when he died. The preliminary script, notes and sketches were collected into the posthumous Tintin and Alph-Art. While the tale, which has the boy reporter rooting out corruption in the modern art world, is sadly uncompleted, it provides about as good a glance at Herge's working methods and inspiration we're ever likely to get.

In his early days, Herge serialized his stories in magazines in black and white and only later collected and printed them in color volumes, often redrawing the stories from scratch. Last Gasp has released a number of these early, original black and white versions in English and they provide a nice point of comparison regarding Herge's considerable artistic growth during this time. So far they've released Tintin in America, Cigars of the Pharaoh, The Blue Lotus and Tintin in the Congo (more on that in a minute). I'm still waiting for an English version of Black Island, which I understand is quite different from its final volume.

Last Gasp also published Tintin's first adventure, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. The art is crude and minimal and shows little of the charm and flair that would later typify Herge's work. It's mostly worth noting because it's Tintin's first adventure and because it shows just how far he came.

The upcoming Peter Jackson/Steven Spielberg film is not the first time Tintin has appeared in the cinema. A number of attempts have been made before, including some odd-looking live-action films. One of the best might be Tintin and the Lake of Sharks, which, though not anywhere near as strong as the core canon, is closer in tone and style to the source material than anyone would have a right to expect. While you can't easily get a copy of the film on DVD, you can score an English "book of the film" on the Internet easily enough.

Ancillary material

Books about Herge and his famous creation abound, many of them released by (you guessed it) Last Gasp and several of them by or edited by one Michael Farr. Farr wrote a biography of Herge, entitled (appropriately enough) The Adventures of Herge, Creator of Tintin (you may also want to check out The Man Who Created Tintin by Pierre Assouline). He also penned Tintin: The Complete Companion, which goes book by book through the series and compares different versions as well as provides valuable information on influences, origins and research methods. Tintin and Co., meanwhile, takes a closer look at Herge's cast of characters.

For my money though, the book to check out is Art of Herge: Inventor of Tintin by Philippe Goddin, which offers scores of early sketches, advertising art, original art, paintings and other illustrations that throw a new light on the man and his work. There are two volumes out now, and I'm hoping a third is on the way soon, as they've proven to be quite invaluable.

Avoid

There's a reason why Tintin in the Congo has (apart from the afore-mentioned Last Gasp release) never been published in America. It's horribly racist. Indefensibly so, with the boy reporter schooling a bunch of big-lipped, dull-witted savages in basic arithmetic and the glories of occupying power Belgium (he doesn't treat the surrounding wildlife much better either). It's an especially egregious attitude considering how Belgium treated its colony and the people who lived there in real life. Herge was deeply embarrassed about the book (which he blamed on his own youth and naiveté), and his later work reveals a great sensitivity and sympathy for other races and cultures that belies Congo's simple-minded bigotry. Still, it's not a book for newcomers -- especially those with an easily offended sense of moral outrage -- to tackle on first blush. In fact, it's probably a book best saved for last.

Next month: Charles M. Schulz