Comics College is a monthly feature where we provide an introductory guide to some of the comics medium's most important auteurs and offer our best educated suggestions on how to become familiar with their body of work.

Today we'll be traipsing through the body of work of one of the most significant (if not exactly prolific) American cartoonists of this modern age, Art Spiegelman.

Why he's important

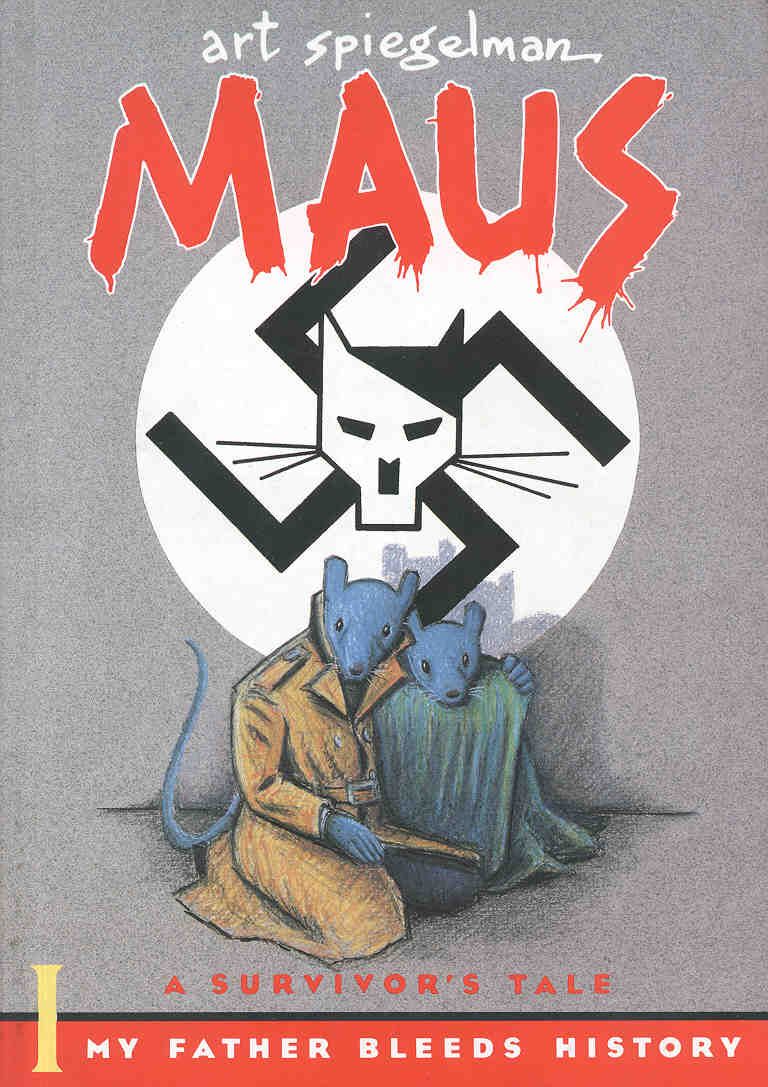

Even if his pen never touched paper again, Spiegelman would have his name etched in comics history until the sun swallows the Earth for Maus, his memoir/biography concerning his father's harrowing time spent first hiding from the Nazis in Poland and then suffering in the Auschwitz concentration camp. It's a complete tour de force from start to finish and one of the few unanimously agreed-upon entries to enter the modern comics canon.

Thankfully he has continued to make and champion comics, however, producing work that, if not equal in stature to Maus (and what really could be?), are often thought-provoking and invigorating nevertheless. A constant cheerleader for the medium, he has (along with his wife, Francoise Mouly) has fought the good fight to get comics to lose their red-headed stepchild status, both by trumpeting a variety of important cartoonists in anthologies like Raw magazine (which he edited with Mouly), and as a critic, scholar and speaker.

Where to start

Well duh. There's a reason Maus won that Pulitzer Prize and all those accolades. Even in the almost twenty years since its completion, the book remains an astounding accomplishment, a thoughtful, emotional examination of both the Holocaust and Spiegelman's relationship with his difficult father. It seamlessly blends straightforward narrative with an almost avant-garde visual style (its key conceit being that the Jews are drawn as mice, the Germans as cats). For many newcomers, young and old, Maus often serves as their starting point into the world of comics.

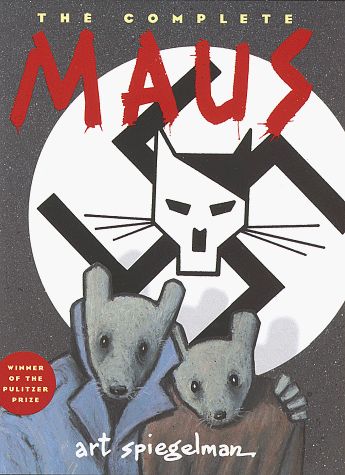

If you can find a copy, and you can play Hypercard files on your computer (and if you do, isn't it time to get a new computer?) you should also try to find The Complete Maus CD-Rom, a nice addendum of notes, photos and assorted research materials used to make the book. (The rumor is a DVD version is in the making.)

From there you should read

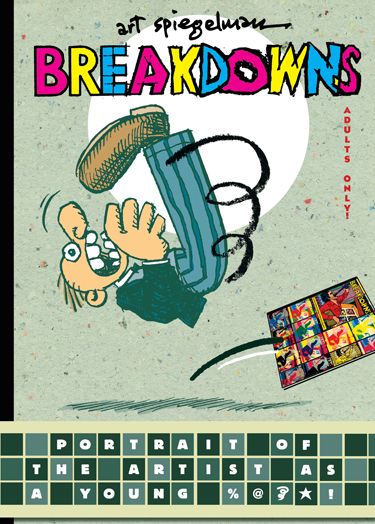

The recently re-released Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist As a Young %@*$! provides a glimpse into Spiegelman's early (sort of) years, and highlights his more formalist, experimental side. It's smart, genre-defying stuff, and those who love seeing the boundaries of the medium get prodded, poked and pushed will especially enjoy what's on display here. Look closely enough, and you can see many of the techniques that he'd later employ in Maus. Originally printed in the late '70s, Pantheon re-released the book in 2008, along with a new, lengthy introduction from the author that sheds some more light on the material and his own personal make-up.

After Maus, Spiegelman's other "big" work is arguably In the Shadow of No Towers, his response to 9/11. It's a series of one-page, landscape formatted essays that combine Spiegelman's interests in the visual underpinnings of the medium and autobiography. Visually, the book is a wonder, full of panels that zig-zag. criss-cross and tumble around one another in an attempt to convey the inner chaos the author felt immediately after the attacks. Thematically and textually, the book is a little weaker, which is not helped by the fact that Spiegelman's strips end at the halfway point and the rest of the book is padded out with a collection of early 20th century comic strips. Still, while Shadow has its faults (and certainly its fair share of critics), it remains, I think, the most logical next step for those interested in exploring his work.

Further reading

Comix, Essays, Graphics and Scraps: From Maus to Now is a nice collection of the artist's work during the 1990s (and before), featuring a variety of illustration and little-seen comics work, including his striking covers for the New Yorker magazine. The book's out of print and a bit hard to find, but it's worth tracking down.

Spiegelman has also written two children's books, Open Me, I'm a Dog and Jack and the Box (the latter done for Mouly's line of young reader comics, Toon Books). Kids will likely enjoy both, though of the two I probably prefer Dog.

You can also see some more of his all-ages work in the Little Lit series of books he edited with Mouly Big Fat Little Lit offers a nice "greatest hits" collection of the anthologies, though really all of the three initial books are enjoyable.

Ancillary material

Spiegelman is equally well regarded for his work as an editor, particularly on Raw magazine. I could write a dozen other posts about that anthology's significance and influence, but suffice it to say that if you want to discover its wonders for yourself, track down a copy of Read Yourself Raw, which collects the first three issues, and/or the three chunky volumes of the Penguin series that followed afterward.

Those looking for more "behind the scenes" type work should check out Be a Nose! a trilogy of sketchbooks from the 70s, 80s and 00s, published by the McSweeney's folk.

For those interested in Speigelman's scholarly side, check out Jack Cole and Plastic Man, a loving tribute to the Golden Age cartoonist, ably and somewhat frenetically designed by Chip Kidd.

Finally, there's Art Spiegelman: Conversations, which, as the title suggests, compiles various interviews he did over the years in one fat book.

Avoid

Unsure of what to tackle after completing Maus, Spiegelman set his sites on illustrating Joseph Moncure March's poem, The Wild Party. The illustrations (this is a strictly no-comics affair) are decent, but somewhat bland and obvious. To my mind this is the weakest entry in his bibliography.

Unless, of course, we're talking about The Narrative Corpse, an interesting but decidedly lackluster comix jam experiment Spiegelman edited, that had cartoonists from all walks of life and genres (Mort Walker, S. Clay Wilson, Will Eisner, etc.) penning three panels of an incomprehensible and ultimately rather dull story of a stick-like figure. It's the sort of thing that sounds fascinating in concept but quickly falls apart when reality intrudes.

Next month: Eddie Campbell