One of the favorite pastimes of comic book fans is how tracking well their favorite (or least-favorite, as the case may be) series is performing on the monthly sales charts. But while many take the data they religiously sift through as gospel, the fact is, as useful as the numbers are for looking at sales trends, they don't represent the actual copies sold of any given title.

The core data for our monthly analysis of the Direct Market in the Mayo Report is the top comics and top trades lists released by and used with permission of Diamond Comic Distributors. This information is compiled by Diamond from sales made to thousands of comic book specialty shops located in North America and around the world. Additional sales made to online merchants and other specialty retailers may be included as well.

RELATED: DC Comics Pulls Ahead of Marvel in March’s Direct Market Sales

The data provided by Diamond includes market shares and various indexes top seller lists including the top 300 comics, the top 50 indie comics, the top 50 small comics, the top 300 trades, the top 50 indie trades, the top 50 small trades, the top 10 book and the top 10 magazines. For these lists, Diamond provides the following data points: quantity rank, retail rank, index, item codes, description, suggested retail price and vendor code.

The quantity rank is the ordering by units sold starting with the best selling item. The ranking is based on the number of units which map to the index value and that number is reduced for returnable items.

The retail rank is the ordering by invoiced amount starting with the item with the highest total invoiced amount. Over-shipped items count as units but have no invoiced amount resulting in a higher retail rank number.

The index is the relative amount of units sold as compared to the benchmark item. It is effectively a percentage multiplier of the sales of the benchmark item. If a comic book had an index value of 50.00 then it sold half as many copies as the benchmark item. An index value of 200.00 means that it sold twice as well as the benchmark item. Diamond uses the best selling Batman issue as the benchmark item. (More on that later.)

The item codes identifies the main item the entry on the list is for. Diamond counts variants of comics and trades at the same price as a single item on the sales like and variants of comics and trades at different price points as different items. This is why "Dark Knight III: The Master Race (2015)" at $5.99 is listed distinctly from "Dark Knight III: The Master Race [Collectors Edition] (2015)" at $12.99 while the numerous variant covers of "US Avengers" #1 which were all at the same price were treated as a single item on the sales list.

The description is the full description of the item including the title, issue number, variant information and a few other bits of data.

The suggested retail price is the cover price of the item.

The vendor code is a three character abbreviation for the publisher.

As crucial as the information from Diamond is, what makes the information useful is having it converted from index values into estimates sales. Essentially, the list is one big, algebraic equation relative to the number of units sold for a benchmark item. This order index value can translate the index values provided by Diamond into estimated sales. Using different known sales can result in slight differences order index values, which in turn results in slightly different estimated sales.

With the Diamond data, the top selling issue of "Batman" is usually the benchmark item.

OK - So Why Is "Batman" The Key Title?

The answer to this question looks to the origin of the index value system, which goes back a few decades. Originally, the sales data was meant for retailers to use as guideline for ordering. The system of indexing titles against a benchmark title was developed by Milton Griepp at Capital City Distribution, using "Uncanny X-Men" as the benchmark title. Since "Uncanny X-Men" was usually the highest selling title at the time, and ordered by every comic book store, it was a logical choice to be the title against which all others' sales were compared.

Keep in mind the original purpose of the list was to aid retailers in ordering back in the early 1980s. I was working at a comic book store at the time, and occasionally helped the store owner fill out the paper order form. Using a calculator, I would multiply the number of copies of the benchmark title the store was selling by the index value for another title to come up with an estimate of how the other title might sell. The owner then compared that with how the title was actually selling in the store and made his ordering decision accordingly.

When Diamond started up a few years later, it adopted a similar index reporting system, but used "Batman" as the benchmark title.

Really, it doesn't matter what the benchmark item is, since it is only relevant for the given list. The value of 100.00 is set by the benchmark item each month, so comparing the index values from month to month is an invalid comparison. When looking at the sales data, we want to know what is relative data and what is absolute data.

So, How Do We Use That Information To Determine Sales Numbers?

Relative data is usually a percentage of some sort, and is limited in scope to a given data set. The index value for an item is relative to the benchmark item for that month. The market shares and percent of the top comics list are also relative measures limited in scope to that month.

Comparing the market share, percentage of the top comics or index value from one month to a market share, percentage of the top comics or index value of another month is a comparison of two relative values with different scope. For example, take two unit percentages of the top 300 comics for the aggregate of the non premiere publishers, 7.76% for January 2011 and 5.13% for August 2016. Based on the percentages, it looks like the non premiere publishers did a better in January 2011 than August 2016, since 7.76% is a larger percentage than 5.13%. The problem is, those are percentages of the total unit sales for the top 300 comics for two different months. The total units for the top 300 comics was an estimated 4,402,738 units in January 2011, and around 9,355,046 in August 2016. The truth of the matter is, the non premiere publishers sold around 341,623 units in January 2011 and around 479,504 in August 2016. And, yes, I picked one of the lowest and one of the highest data points to illustrate comparing relative data across months is invalid.

Absolute data is a metric which is valid across time. By converting the relative index values for the items each month to an absolute metric of estimated sale, we can safely compared sales estimates across months.

RELATED: “DC Universe: Rebirth†Could Have Sold Even More Copies

I take the sales data provided by Diamond, clean up the titles and mix in some other information, such as shipping date. I also compare the issue sales to the sales of the previously released issue. In those comparisons to the previous issue, the all known sales, including reorder activity, are included for the earlier issue. This issue-to-issue change helps provided sales trending for the titles. While I could compare sales over a longer time period, I personally don't see much point in that given how much the industry and marketplace change over time.

The version of the top comics list I release every month on CBR includes the quantity rank, the index, the price, the publisher code, a cleaned up version of the title, the issue number, an indicator if the sales are reorders, the estimated number of units, the issue number of the previous issue used for comparison, the estimated number of units for the previous issue, the number of units the sales increased or decreased from that previous issue, that increase or decrease as a percentage of the previous issue sales and the number of weeks late the issue was. For my podcast, I have a few other data points such as the price of the previous issue, the change in the price (if any), how many times the item has been on the sales list before, the expected ship date, the actual ship date, the solicitation blurb and the sales history among other things.

Putting All The Pieces Together

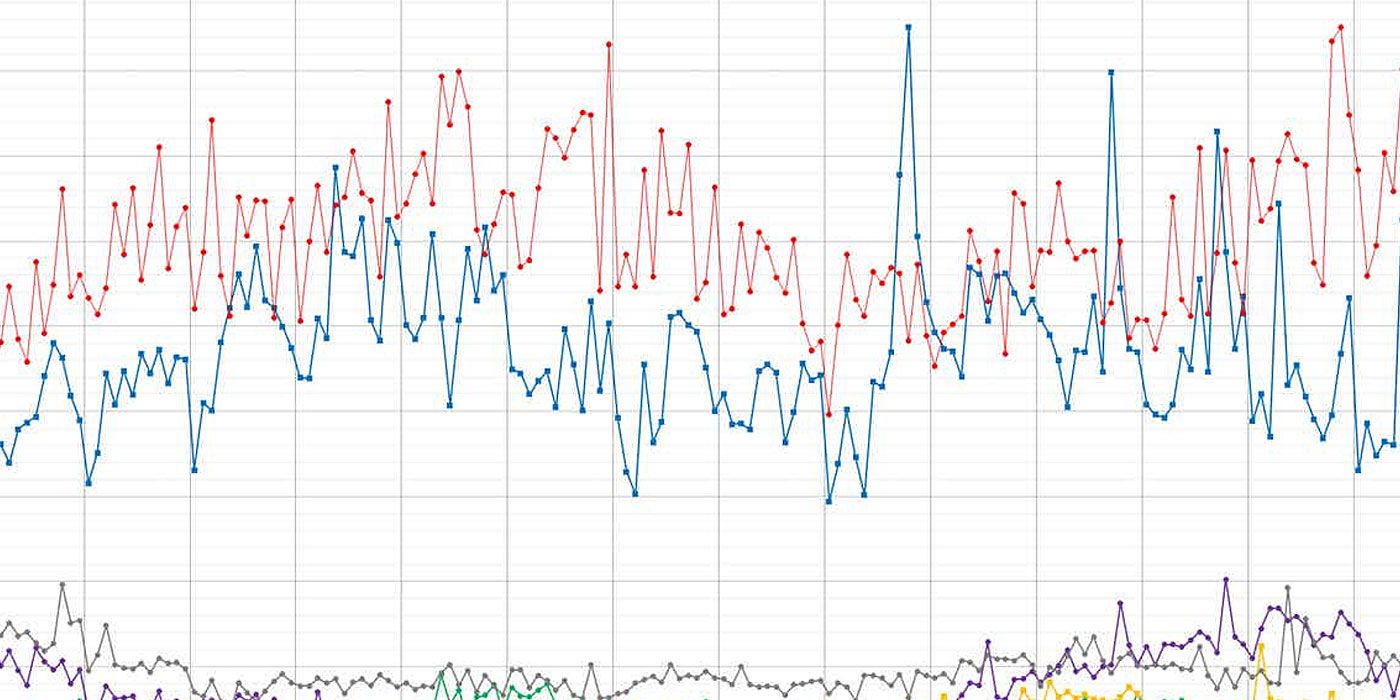

When I chart the monthly sales of the top 300 comics by publisher, segments in the first stacked bar chart represent the number of units for each publisher stacked with the publisher with the most sales in the top 300 comics at the bottom to the publisher with the least at the top. For the purposes of this chart, the non-premiere publishers are all in a single grouping called "Other Publishers." Marvel is red, DC is blue, Image is yellow, IDW is cyan, Dark Horse is green and the other publisher group is purple. These same colors are used in the episode images for my podcast and on the title category charts. The bar chart is currently calibrated to a maximum of 10,000,000 units of sales in a given month in an attempt to keep the bars at the same scale from month to month. If the top 300 comics ever exceeds 10,000,000 units, I'll have to recalibrate the charts. It would be a nice problem to have.

The second bar chart has the month-to-month changes in units for each publisher. Increases are stacked above the zero point in the middle of the chart with the largest increase in units closest to zero to the smallest increase at the top. Decreases are stacked below the zero point in the middle of the chart with the largest decrease in units closest to zero to the smallest increase at the bottom.

The third bar chart has a single gray segment representing the net change in sales from the previous month. If it is above the zero point in the middle of the chart then sales were up for the top 300 comics for the month. If it is below the zero point in the middle of the chart then sales were down.

These days, a significant number of titles shipping multiple issues per month. AS a result, in addition to tracking issue-to-issue changes, I'm tracking month-to-month changes in sales on a per title basis. To do this, the titles are put into various categories:

- Continuing Titles (Gained Sales)

- Continuing Titles (More Issues)

- Continuing Titles (Stable Sales)

- Continuing Titles (Fewer Issues)

- Continuing Titles (Lost Sales)

- New Titles

- Returning Titles

- Suspended Titles

- Defunct Titles

- Annuals/Specials

- Reorders

Continuing Titles (Gained Sales) are title which was published in the previous and current months with the same number of issues released each in both months which sold more units in the current month than in the previous month. This category can only represent an increase in sales.

Continuing Titles (More Issues) are title which was published in the previous and current months with more issues released in the current month than the previous month.This category usually represents an increase in sales but can contain titles which dropped in sales from month-to-month. For example, one high selling first issue in the previous month followed by a sharp second issue drop and a third issue drop in the current month could result in a loss in sales despite more issues released.

Continuing Titles (Stable Sales) are title which was published in the previous and current months with the same number of issues released each in both months with a drop of no more than 250 units between the current month sales and the previous month sales. The 250 units is admittedly an arbitrary number and I might change it later. Despite the charitable name, this category can only represent a drop in sales.

Continuing Titles (Fewer Issues) are title which was published in the previous and current months with fewer issues released in the current month than the previous month. This category usually represents a drop in sales but can contain titles which increased in sales from month-to-month. For example, two low selling issues in the previous month followed by a huge spike in sales on a single issue released in the current month could result in an increase in sales even with fewer issues released.

Continuing Titles (Lost Sales) are title which was published in the previous and current months with the same number of issues released each in both months which sold fewer units in the current month than in the previous month. This category can only represent a drop in sales.

New Titles are new titles or new volumes of existing titles. In many cases, these are simply replacing a recently concluded title and aren't as new as the category name might seem to imply. Since there are not previous sales to compare against, New Titles represent an increase in sales each month. Since this category can only represent an increase in sales.

Returning Titles are titles which were in the Suspended Titles or Defunct Titles and shipped in the current month. Returning Titles represent an increase in month to month sales and therefore has the same number of units on both the units and delta charts.

Suspended Titles are the titles which didn't ship this month but are expected to ship in the future. Suspended Titles represent a decrease in sales from month to month but not sales drops for the titles since sales can't be considered lost until the next issue ships with lower sales. Regardless, retailers can't sell comics which haven't shipped. Titles can drop below the radar of the top 300 comics list and the sales are considered suspended when that happens.

Defunct Titles are ones believed to have ended with the previously shipped issue. Defunct Titles represent a presumably permanent decrease in month to month sales with the caveat that these titles might get continued as some point in the future such as any title which reverts to a previous numbering sequence, acting as continuations of titles previously considered defunct. Any title with no future issues solicited is considered to be Defunct and as a result, while most of these titles have ended, some might be quarterly or just have a lengthy gap in the release schedule.

Annuals/Specials are the annuals and specials which are part of a title but aren't a regular issue of the series. This category can increase or decrease the total units for the top 300 comics list depending on the number of annuals and specials that shipped in the current and previous month. As soon as I can get my system to correctly identify other one-shots, they will go into this category and it will be renamed One-Shots.

Reorders are items which have placed on the list in a past month and have managed to get enough additional sales for an issue to get onto the top 300 comics again. Reorders can increase or decrease the total units for the top 300 comics list depending on the number reorders in the current and previous month.

When I chart the sales by title category, segments in the first stacked bar chart represent the number of units for the category stacked from the largest category at the bottom to the smallest category at the top. Once again, the bar charts is currently calibrated to a maximum of 10,000,000 units of sales in a given month in an attempt to keep the bars at the same scale from month to month.

The second bar chart has the month-to-month changes in units for each category. Increases are stacked above the zero point in the middle of the chart with the largest increase in units closest to zero to the smallest increase at the top. Decreases are stacked below the zero point in the middle of the chart with the largest decrease in units closest to zero to the smallest increase at the bottom.

The third bar chart has a single gray segment representing the net change in sales from the previous month. If it is above the zero point in the middle of the chart then sales were up for the top 300 comics for the month. If it is below the zero point in the middle of the chart then sales were down. This is the same value as the third bar chart in the bar charts by publisher.

The horizontal bar charts for each title category show the change in sales from the previous month stacked with the largest change in sales at the top and the smallest at the bottom. Increases in sales are always to the right of the axis while decreases are to the left of it. For categories which can have both increases and decreases in sales, the items are sorted from the largest increase at the top to the largest decrease at the bottom. The bars for each title use the same color coding as for the publisher bar charts.

Since the Continuing Titles (Lost Sales) is usually huge, only drops over 5,000 units are charted.

When I chart the sales of a title over time, the scale of the chart is determines by the maximum sales of the title. Usually the horizontal lines are placed every 10,000 units. For lower selling titles, they are sometimes placed every 5,000 units. On rare occasion, sales are low enough that it makes more sense to place the horizontal lines every 1,000 units. The timeline is by year, month and week of month and the charts only contain issues for which my system knows the shipping dates.

Remember, These Are All Estimated Numbers

It is important to remember that are sales estimates and not an exact number of copies sold. The estimate is mathematically correct, and is as accurate as the source data from Diamond.

Keep in mind this information is what is invoiced to retailers, not what the publishers sold to Diamond, or what the readers purchased. Diamond orders from the publishers some amount above what the stores ordered from Diamond. These extra copies cover damages and reorders. The size of this buffer varies from item to item.

Typically when people claim the estimates are wrong they are unclear about what the estimates are measuring. I've had creators claim the estimates are incorrect because they are lower than the numbers they see on royalty statements. The estimates should be lower than the number on the royalty statements for a couple of reasons. The top seller lists only go so deep and there are a lot of items under the radar of those lists.

Any sales outside of Diamond obviously won't be reported by Diamond. Example of this include convention sales, subscriptions and other sales channels like mass market outlets like Amazon and Wal-Mart. Royalty statements and orders to publishers will include those numbers, while our sales estimates won't.

Obviously not all copies of every item are sold to readers. The number of units invoiced to retailers is always going to be somewhere below the number of units which went from the publisher to Diamond and above the number of units sold from the retailers to readers. I'd love to report on sales to readers but that data isn't available. I'd be more than happy to offer my services as a data professional to organizations like ComicsPro to help collect and report on sales to readers. Point of sales information on reader buying patterns would open end new avenues of research on comic book sales such as how price increases and events influence the buying habits of readers. This data could potentially provide very specific insights that could result in actionable recommendations for retailers and publishers which could result in better sales.

From a publisher perspective, the buyers of the comics are the stores, not the readers. It is the sales invoiced to stores which determine which titles continue and which don't.

Generally speaking, sales to retailers are non-returnable. There are cases in which comics are either offered on a returnable basis or become returnable because they are late or substantially different from how they were solicited.

While a publisher may list a comic as sold out, it is entirely possible that many retailers still have copies available for sale. A press release indicating a sell out means the publisher has no more copies to send to Diamond. Since the publisher usually sets the print level based on the orders they get from Diamond, it is possible to engineer a sell out by not over-printing.

The result of this aspect of the system is that it places the risk on the retailers as they have to order the comics months in advance and try to predict how well they will sell. Retailers are understandably conservative when ordering rather than risk getting stuck with tons of unmovable merchandise. A result of this is that sometimes the retail community wind up chasing the sales of a title either up or down. Neither is particularly great for the industry as a whole. Retailers that order too many copies end up eating into their profits and tying up money that could have been used on comics that would have sold. Retailers that order too few copies end up making fewer sales than they could have. But it is better not to have made as much as possible than to have lost money by ordering too many copies.

While information about the actual comic book sales to readers would be very interesting, don't expect to see that information anytime soon. There are significant challenges to collecting that data given the nature of the comic book market. Most comic book stores are small, independently owned businesses. While some comic book stores are part of a chain and might have sophisticate sales tracking software, not all comic shops use a point-of-sales system. The reason book sales to readers can be tracked is because of services like BookScan which collects data from various retails that is recorded at the time of purchase. When you buy a book at Borders or online at Amazon, that sale is recorded and that information is used to generate the top selling book lists. This relies on the retail outlets collecting the data which usually done by the cash register system when the checkout clerk scans the book with the bar code reader. And while some comic book stores use bar code readers and point of sales software, no system exists to collect this information across the industry and report on it. Even if such a data collection system existed, getting a majority of comic book stores to submit data to it would be a potentially difficult task. So, until that happens, the best data available on comic book sales is from Diamond and reflects sales to the comic book stores.

Hopefully this clarifies the what data Diamond provides and how I convert that data into the sales estimates information I report on each month.