Perhaps it's because we tend to think of it as a very narrowly defined genre with certain expectations and limitations, but generally when we hear the term "horror comics" we tend to think of Tales From the Crypt or The Walking Dead and not so much anything from the art comix crowd.

And yet I hope it's no slam against Al Feldstein or Robert Kirkman if I say that within the indie scene a number of talented cartoonists have produced some brilliant and truly terrifying work. Josh Simmons, for example, has been steadily building an impressive repertoire of horror-based work with books like House. Certainly Hans Rickheit's surreal/grotestque The Squirrel Machine falls more easily under the "horror" label than just about any other.

But there's one alt/indie cartoonist whose work stands head and shoulders above everyone else in the "ye gods, that's frightening department." Although he hasn't produced (or at least published) a huge body of work, what has been released over the past fifteen years has been of such stellar, nightmarish quality as to astound readers lucky enough to stumble on it and influence a number of artists. I'm speaking of Al Columbia.

(Note: Disturbing images and swear words lurk below the jump. You've been warned.)

Now is actually an excellent time to be talking about Al Columbia, as the mercurial cartoonist ahas not just one but two books coming out, from Fantagraphics and IDW respectively. Considering that his last solo outing was released in 1995 (that's not counting various anthologies and the two-issue comic he did with Ethan Persoff, The Pogostick), one can be forgiven for saying it seems like the damn has broken.

Those who aren't very familiar with Columbia's work may know him best as the guy who "ruined" Big Numbers, the Alan Moore/Bill Sienkiewicz collaboration that was going to be the bee's knees back in the heady days of 1990. Only 19 years old, Columbia was hired as Sienkiewicz's assistant, and then ended up taking over the art on the project when Sienkiewicz opted to bow out after the second (or maybe third, it's not really clear) issue. Columbia started working on the fourth issue, but due to pressure of production, the scope of the project and the realization he'd have to mimic his mentor's art style for a considerable length of time, he had some sort of nervous breakdown, tore up the original art, and disappeared for a bit. Big Numbers was never finished.

At least, that's one of the rumors. There are others floating around.

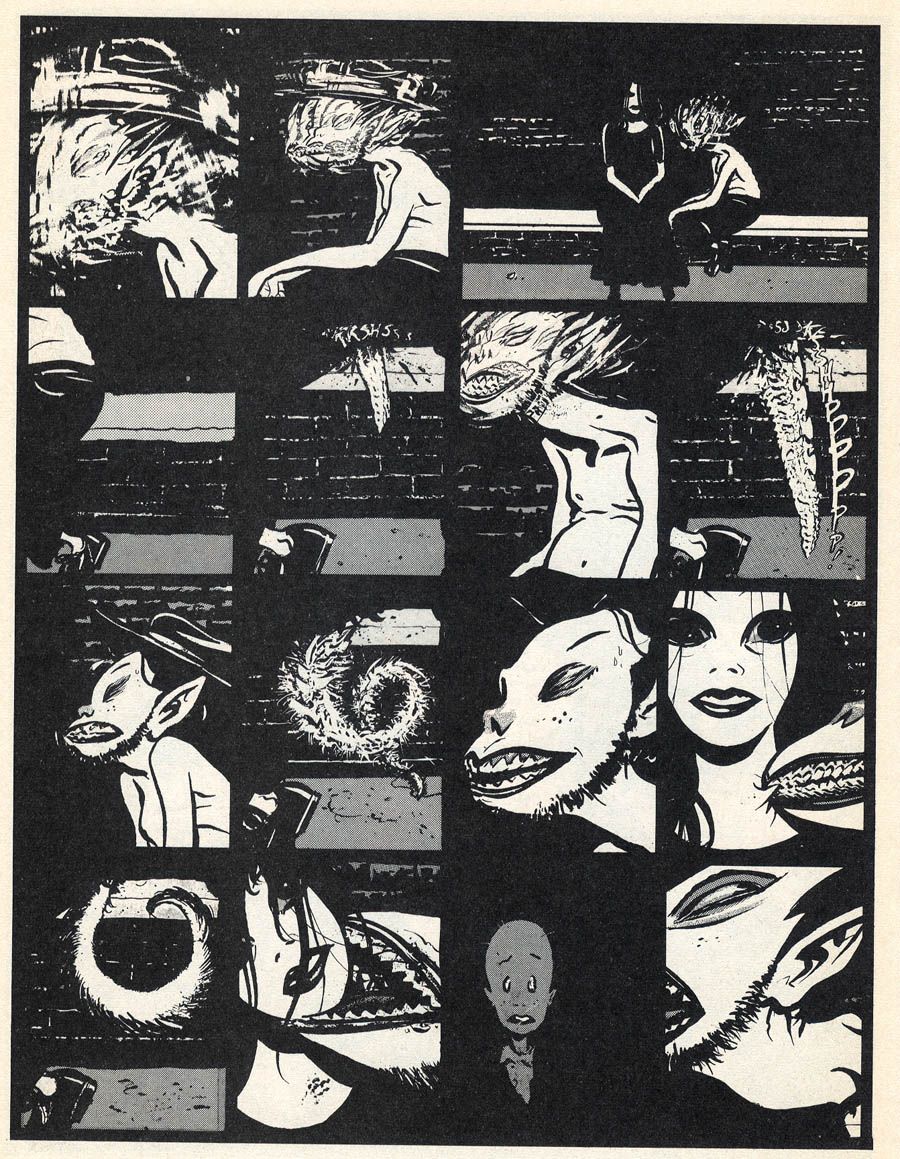

When Columbia did resurface, it was 1994, with the first issue (though, perhaps in a winking nod to Image, it was presented as "Issue 0") of The Biologic Show. By this point, any lingering traces of Sienkiewicz's style had faded into the background. Realism gave way to a cartoonish grotesquery. The stories collected in that first issue flow in a surreal, unsettling fashion, with a decided emphasis on mutilation, and vivisection.Eyes constantly leered. Teeth always seemed to be bared.

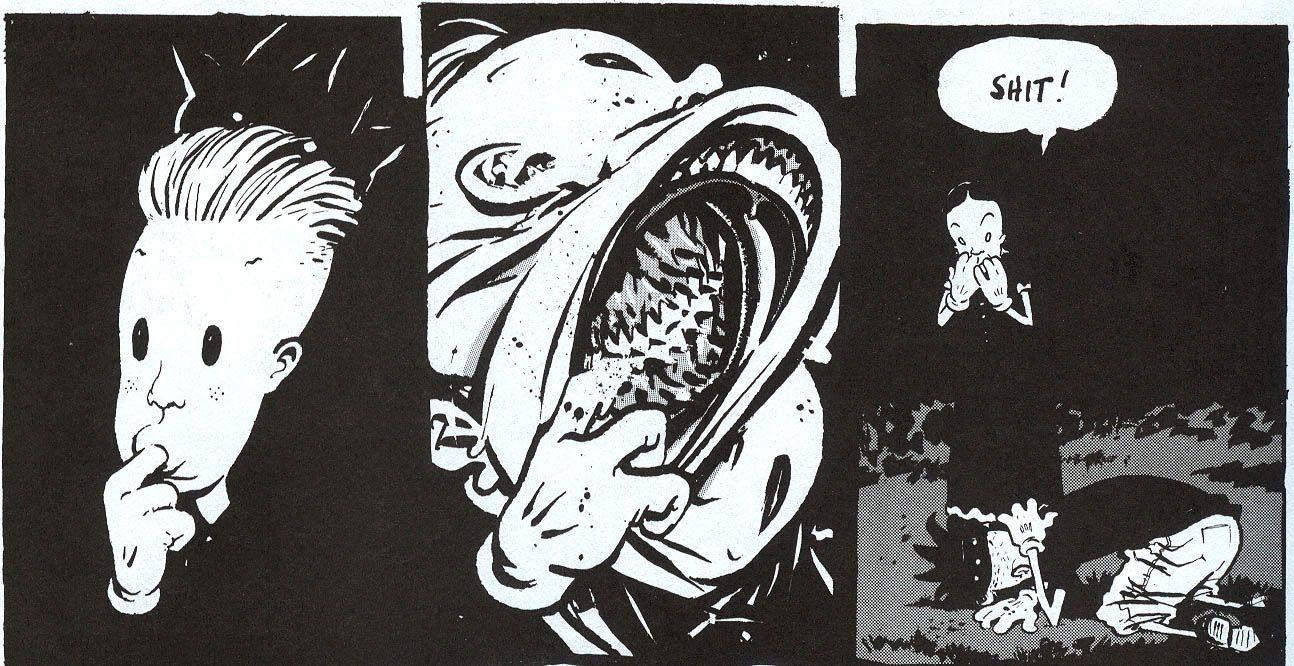

Not everything in that comic work, but the best entry by far was "Tar Frogs" a "Pim & Francie" story featuring two elfin children who come acropper of the mean old man next door. The story starts out with the boy dissecting a dog's eye and only gets more unsettling from there. Influenced by filmmakers like David Lynch no doubt, "Tar Frog" doesn't follow a overt narrative logic as it does shift from one bizarre episode to the next, each building upon the other in a nightmarish frenzy. Certainly it's a useful story to read if you ever wanted to know why cartoon characters always wear those white gloves.

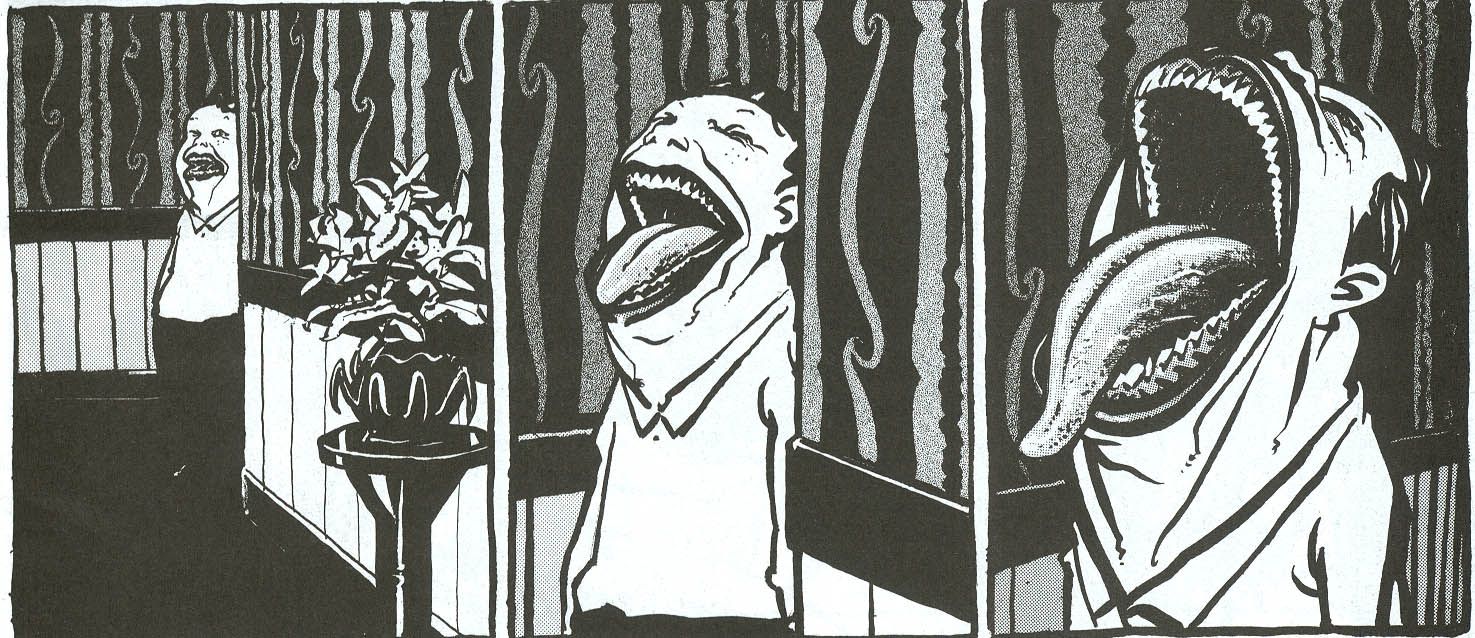

Columbia upped the ante with the next issue, No. 1, which featured Pim and Francie yet again (Columbia re-uses the same cast of characters, like the innocent fool Seymour Sunshine, constantly. They seem to inhabit the same universe and death is merely a commercial break until the next episode. Indeed, the new Fantagraphics book stars Pim and Francie). Here, the pair are menaced by a knife-wielding two-headed girl (again, another reoccurring character). The duo get separated and Francie ends up in a car with a possible pedophile while Pim comes across a wolf-boy known as Knishkibibble who, in the sequence below, starts to change shape:

It's here we start to see a lot of the tropes Columbia would use regularly in his work take shape: Children in danger. A blending of supernatural and real-life horrors. Serial killers. Transformation. Reptile eyes. Disturbing smiles. A unhealthy interest in knives. The slow realization that all is not well. In Columbia's comics, monsters lurk down every alleyway, and there is no escaping them. Columbia's universe isn't merely uncaring or godless. It's predatory.

Apparently something of a perfectionist (another rumor) he quit the Biologic Show after that "first" issue and began contributing the occasional short piece to alt-anthologies like Zero Zero and Blab. His first entry showed up in Zero Zero #4 and was a beaut. Entitled I Was Killing When Killing Wasn't Cool, it was both a distillation of his work to that point and a sign of how far he could take things.

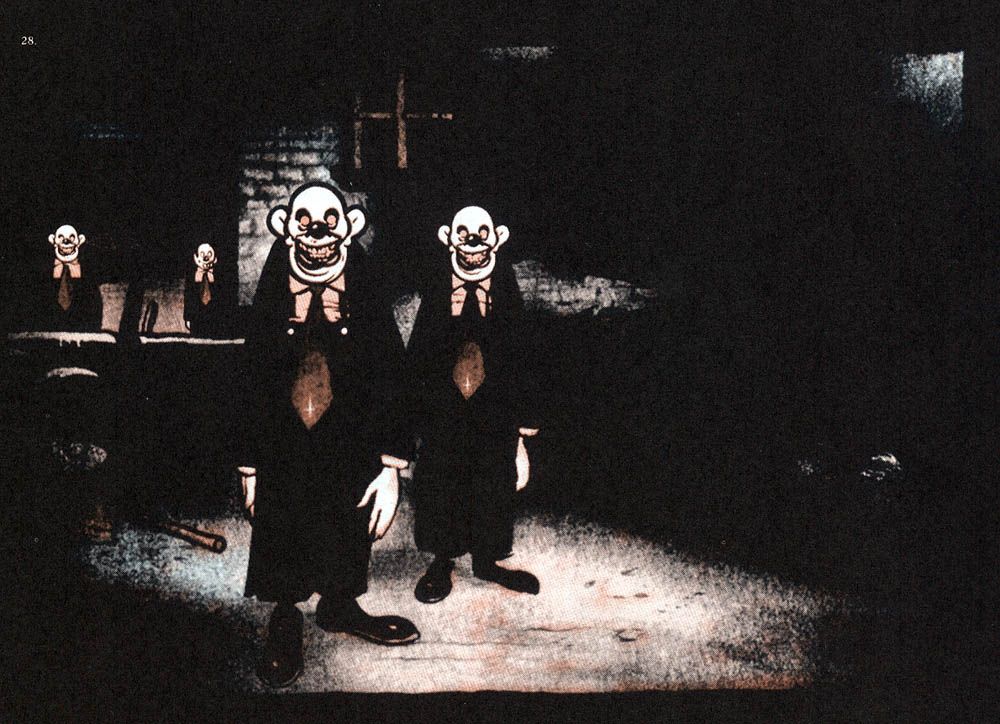

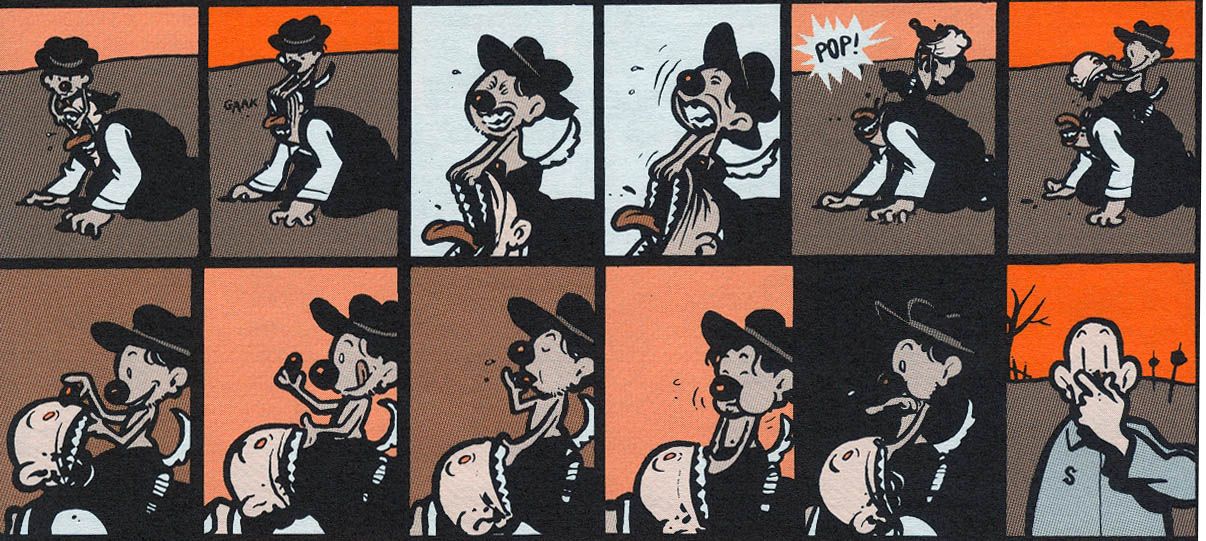

Here, Columbia abandons his rougher style for a something more tightly controlled. Aping American animation style of the early 20th century, especially the Fleischer Brothers, everyone suddenly became a lot softer, rounder and cuter, which, of course, only served to make the surreal violence that more horrific.

Columbia would pretty much stick to this style for his comics from here on out, although he'd incorporate PhotoShop tricks and computer text occasionally.

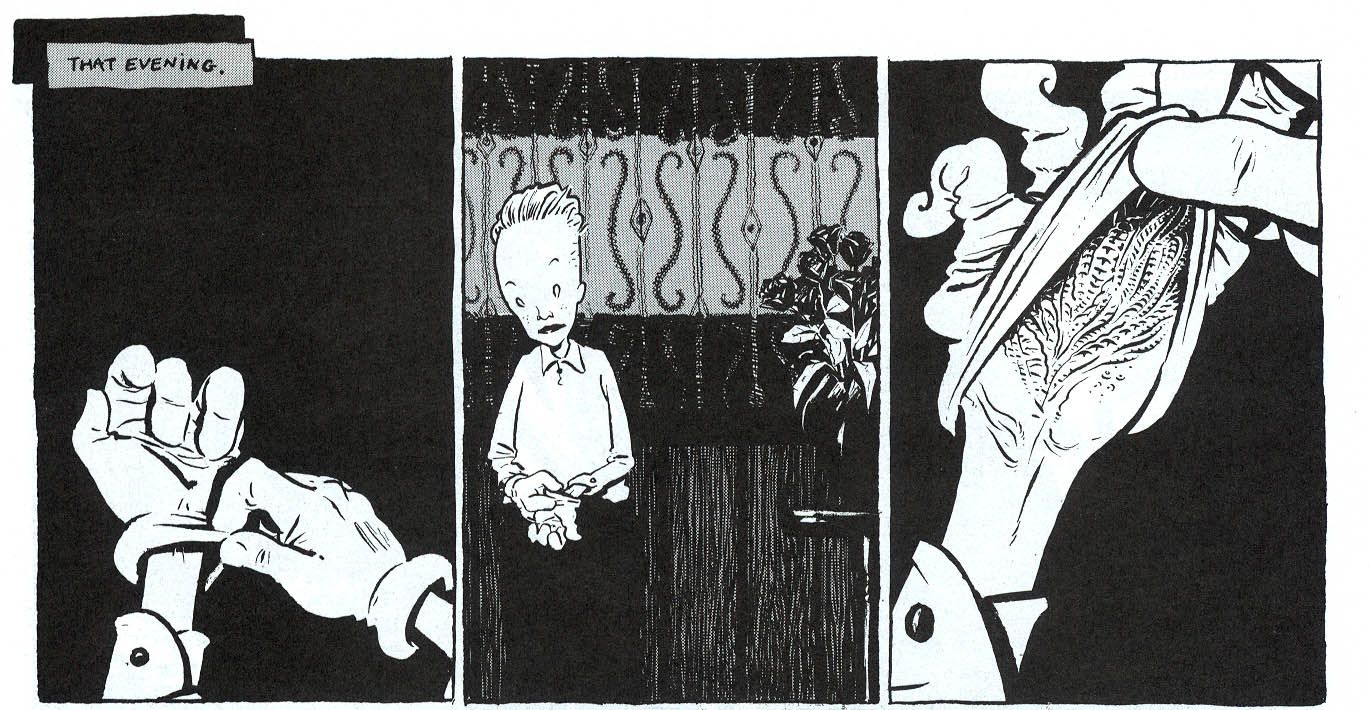

His interest in animation extends to his layout of the story, as he breaks everything down to a tiny panels and frequently slows the motion down to heighten the tension. His interest in unnerving the reader continues unabated as well, however, as Seymour Sunshine and the now pint-sized Knishkebibble take on a killer, only to discover a more nefarious character literally hiding in the mirror.

As Tom Spurgeon best put it:

[The story is] remarkable not just for Columbia's typically jaw-dropping display of once-in-a-generation art chops, but because he allows the reader to slowly realize, like the best horror films, that the adventure you are currently enjoying is going to end in ways too terrible too imagine, your face to be rubbed into black, relentless evil that makes you small before it does you in as painfully as possible, a spiritual snuffing as well as physical killing.

Indeed, what makes Killing -- and Columbia's work in general -- so stellar is not merely the artist's interest in the grotesque or severed limbs as much as his ability to set and sustain and genuinely creepy mood, something that his meticulous drawings only serve to enhance.

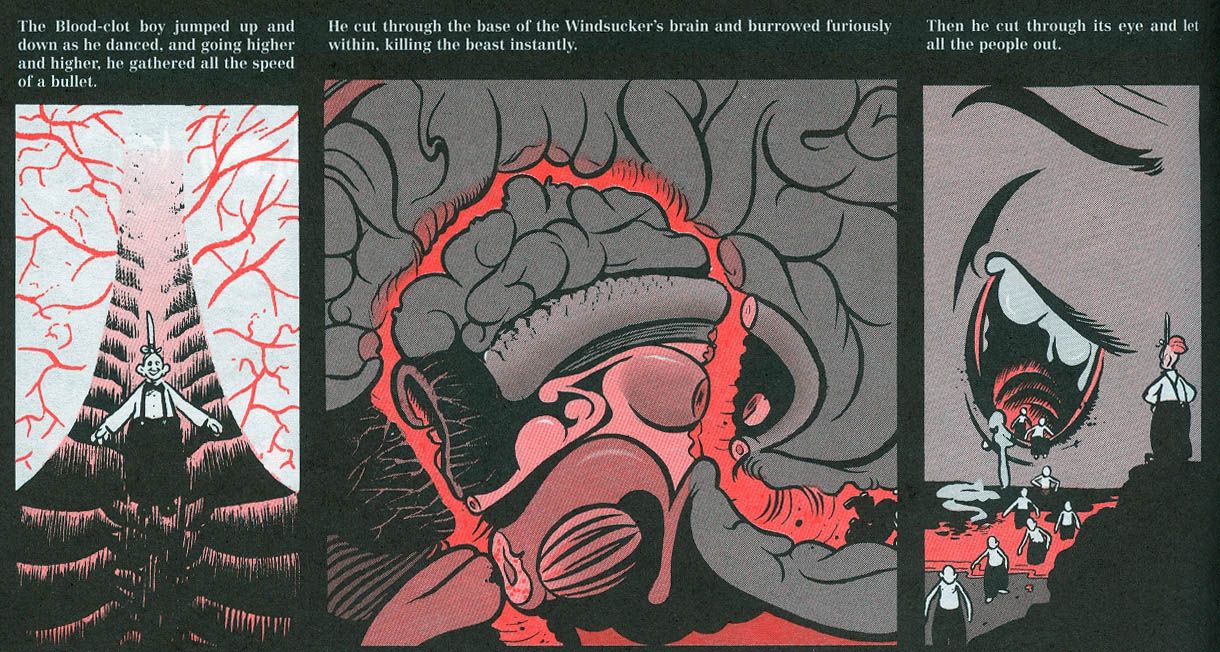

Besides old cartoons, Columbia also seems to have an interest in folk tales, as evidenced by stories like The Blood Clot Boy, which appeared in Zero Zero #16.

Here Columbia takes all the gruesome elements of your average fable -- the dark things that Disney tends to try to gloss over -- and increases their visceral impact considerably, though he leavens things somewhat by providing a loquacious, wry narrator to help detail the proceedings.

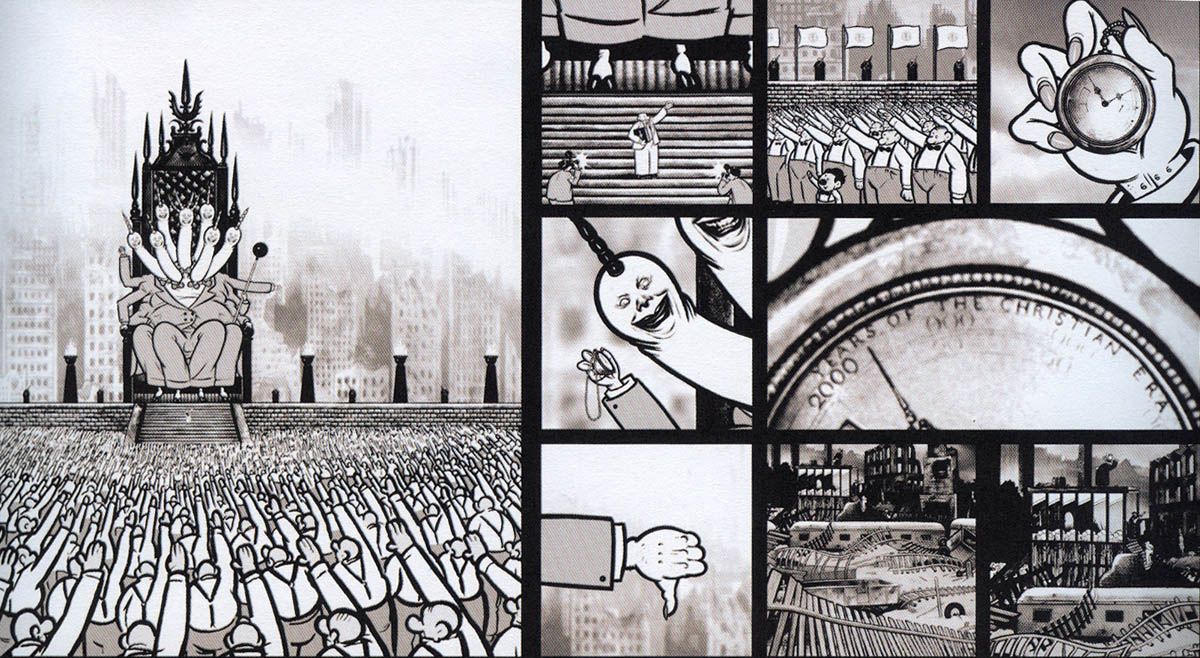

But by far Columbia's best work during this period remains The Trumpets They Played, which you can find in a copy of Blab #10. The story is Columbia's interpretation of The Rapture/Book of Revelations, with Seymour and Knishkebibble facing off a host of horrifying Biblical monsters, including the seven-headed Beast of the Sea. Columbia packs his tiny panels with as much detail as possible, most of them filled with what would normally be cute creations doing horrible things. At one point he shows a baby in an empty room playing with a loaded gun (and yes, it ends just like you imagine it might). He then pulls back to the adjoining room to show a long-nosed man copulating with ... something. Then he pulls back even further to an eventual full-page spread that shows the whole city engaged in one type of depraved "end of days" debauchery or another.

Seymour and Knishkebibble attempt to escape all this, but, as I said before, there is no escape in Columbia's world. The horror and eventual end can only be delayed. Which in this case means Nazi-like rallies and mass executions.

The frustrating thing about all this great work is it has yet to be collected. Neither of Columbia's two new books, to the best of my knowledge, collect or reproduce any of the material mentioned above.

That seems a real shame. These comics remain some of the most striking and influential work produced in the 1990s. You can see elements of his work, not just in horror-themed tales like Squirrel Machine but in more benign material as well.

I can't even begin to guess at the reason this work has taken so long to get collected. Whatever the cause, I hope we don't have to wait too much longer -- Columbia's career, as sporadic as it is, deserves the type of critical evaluation and reconsideration a nice "done in one" book would encourage. His work is dark, certainly, but no less striking or beautiful because of that.