Welcome to Collect This Now, a weekly (or, if I’m hungover, semi-weekly) column where we look at good comics that for whatever reason have never been translated, archived or just collected into trade paperback.

It's a pretty good time to be an English-only Eurocomics fan. A number of great contemporary artists and cartoonists that have been reshaping the comic book landscape on the other side of the ocean are slowly but steadily having their work translated and released here. In the past few years we've seen great works by such folk as Lewis Trondheim, Dupuy and Berberian, Joann Sfar, David B. and many others available here thanks to the hard work of a number of small publishers.

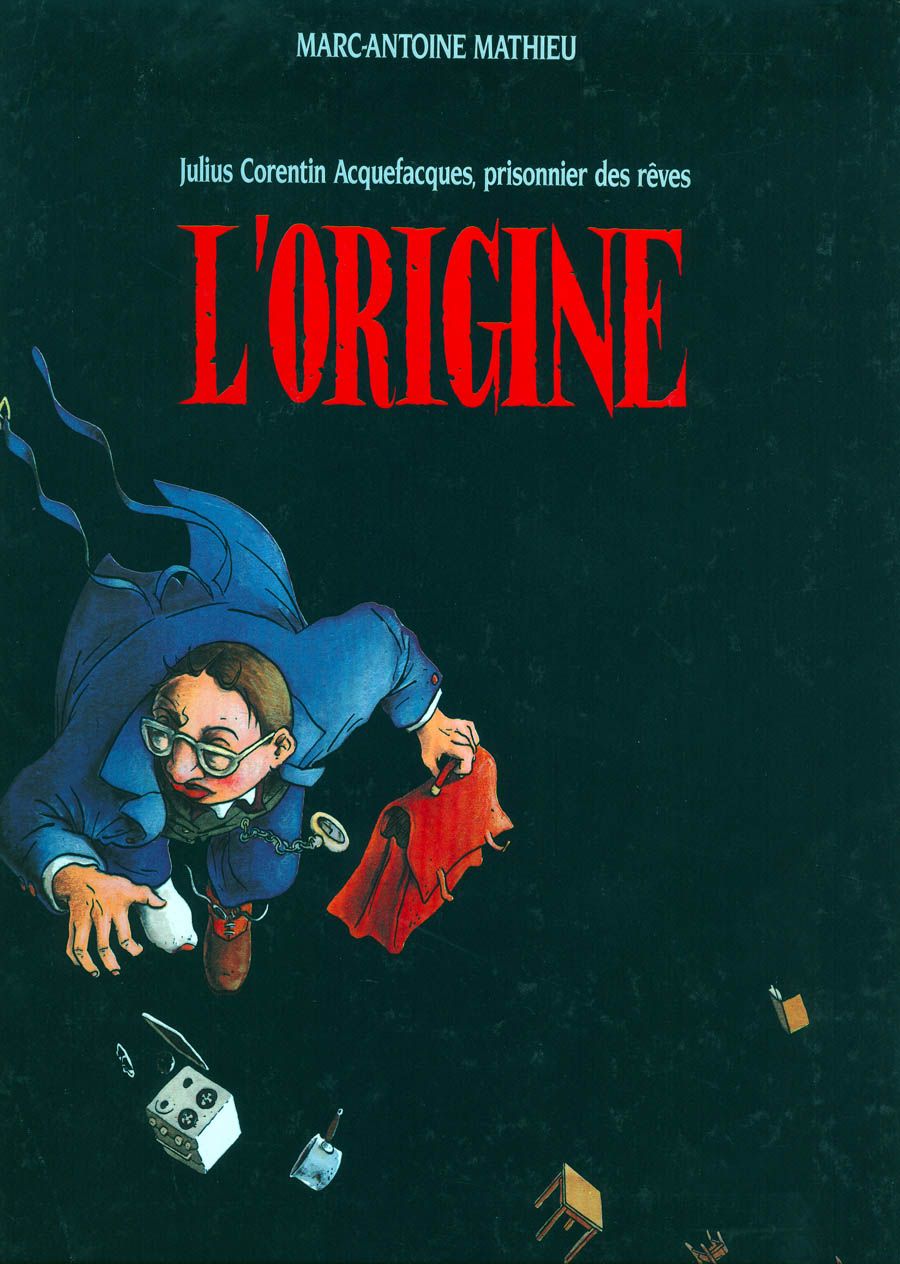

There's one author (well, probably more than one, but I have to limit myself for now), however, whose absence seems rather gaping to my mind and that's Marc-Antoine Mathieu. More specifically, it's the series that' he's best known for: Julius Corentin Acquefacques, prisonnier des reves.

Very little of Mathieu's work has been published at all in the U.S. Only two books so far that I know of are available: Dead Memory, released by Dark Horse in 2003; and The Museum Vaults, published last year by NBM as part of the Louvre series of graphic novels.

Both Memory and Vaults (which I reviewed last year) are entertaining books, but neither of them achieve the sort of formulist-inspired frenzy that the Acquefacques series does (though Vaults gets close at times). It's in the Acquefacques volumes that Mathieu explores both the limitations and depth of the comics medium while at the same time our own very real relationship with time and space.

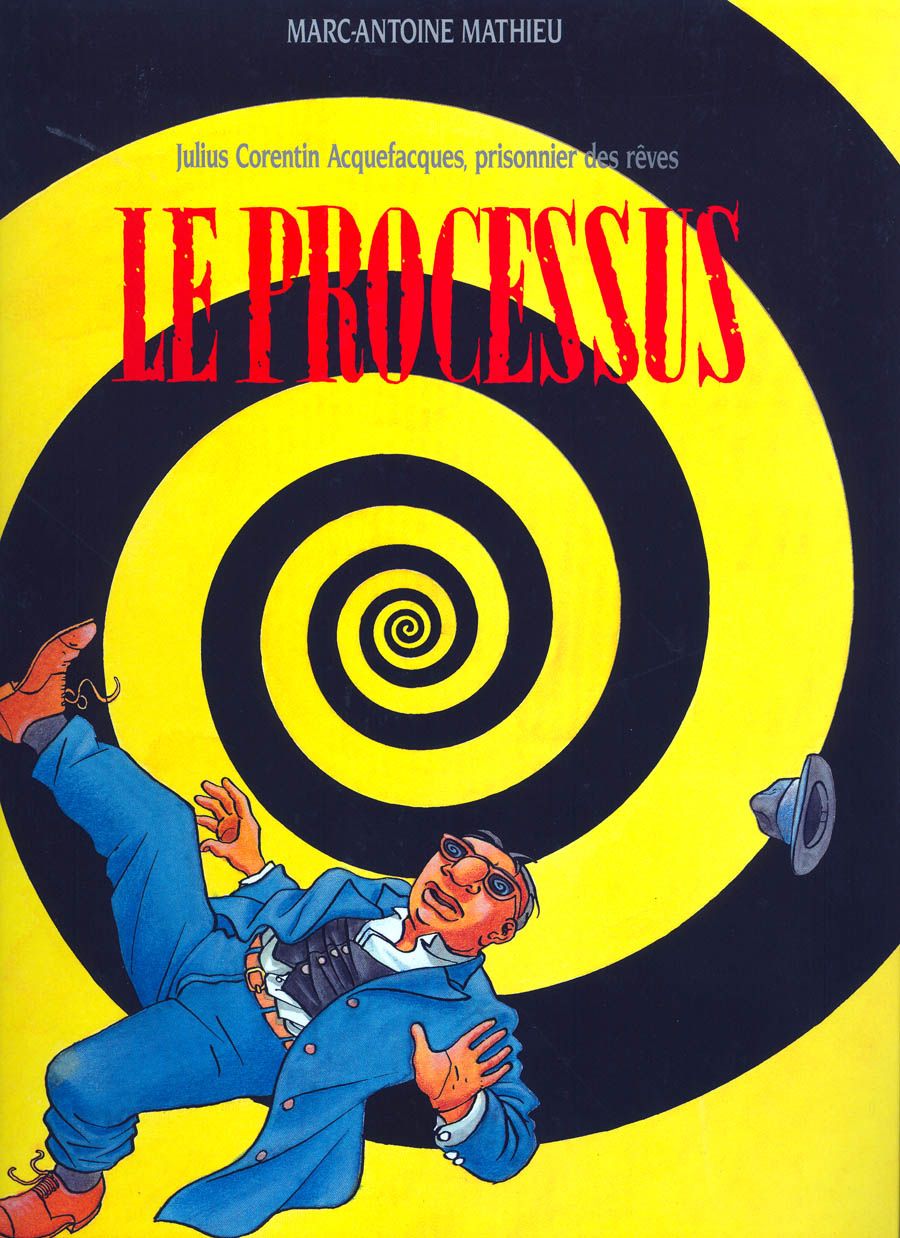

There are five books in the series to date: L'Origine, La Qu ... Le Processus, Le Debut de la Fin and La 2,333e Dimension. Of the five, I only own the first and third books, and that's what I'll be attempting to talk about here.

In L'Origine, we meet our hero, a spectacled bureaucrat who lives and works in an impossibly crowded and unnamed city for the Ministry of Humor.

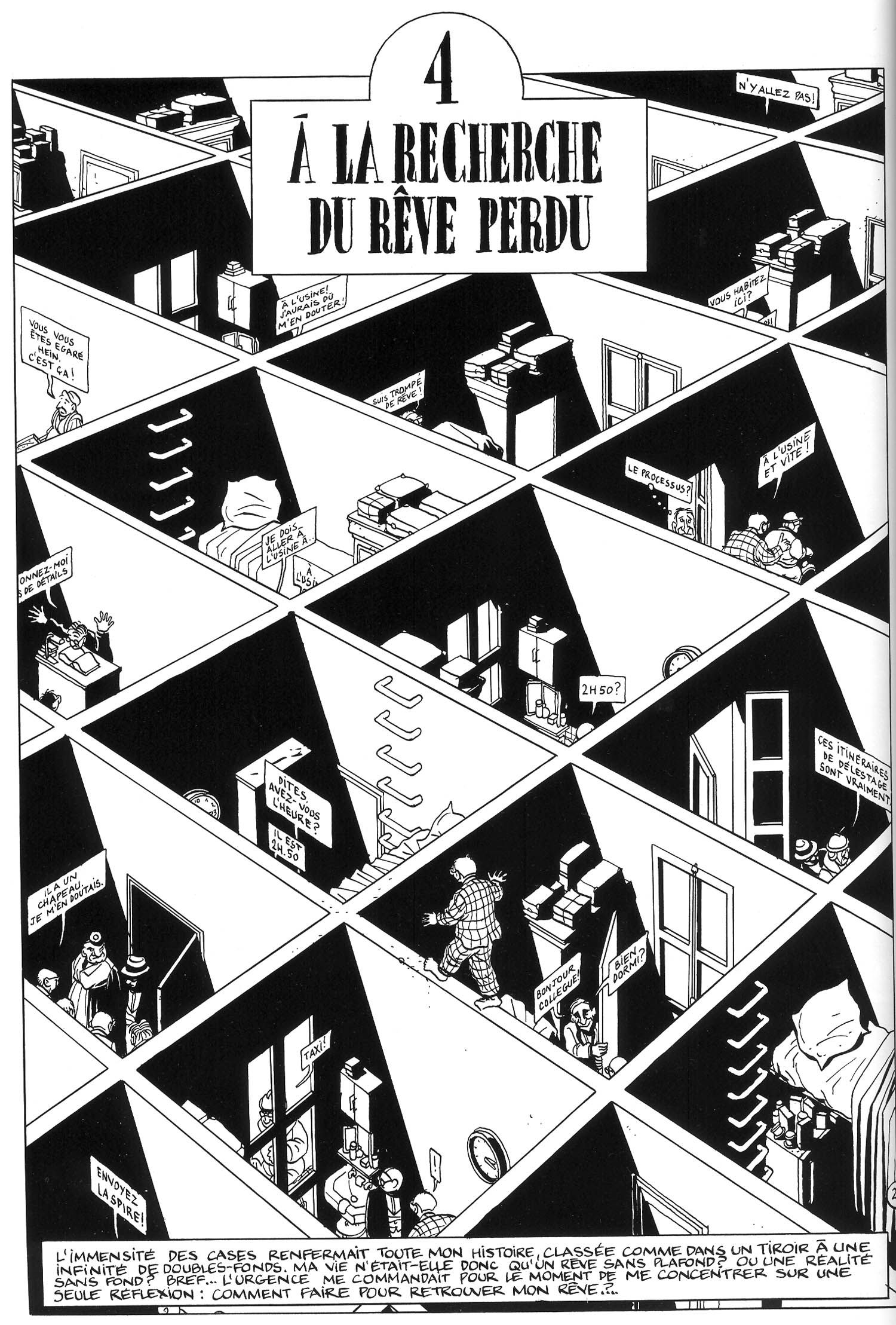

As the book opens, Mathieu gets a letter in the mail which contains a page of the very same comic we're reading. Page four to be exact. Julius is perplexed -- how could some artist know exactly how he started his day? And what does the word "'l'origine" scrawled along the top of the page mean? The word does not seem to exist in Julius' world, perhaps because he lives in a city that seems to have no beginning or end but simply is.

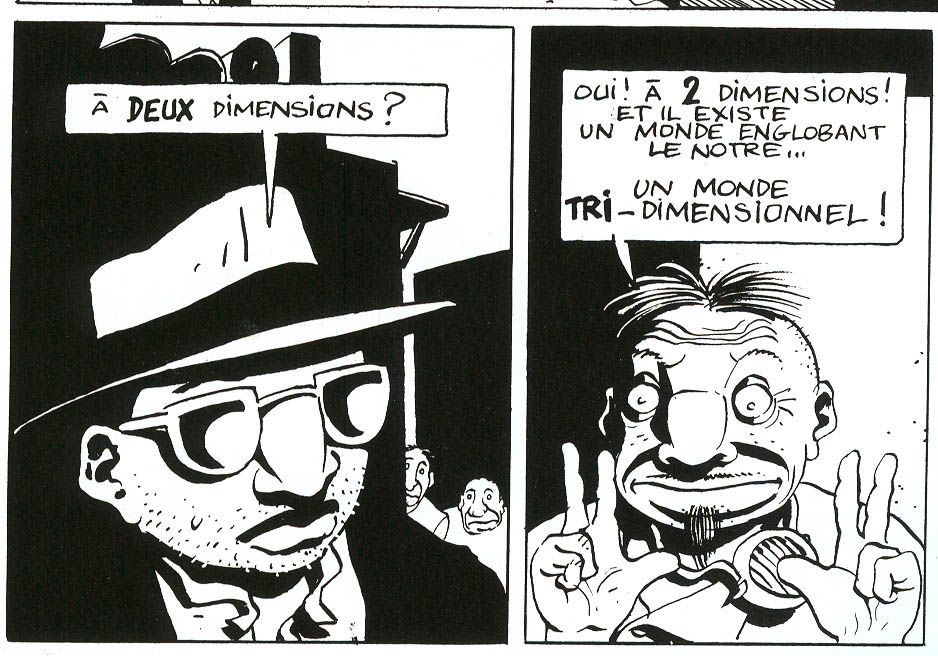

Anyway, as Julius attempts to unravel this mystery, more and more pages are sent to him, some from later in the book, foretelling his future (Mathieu gets a nice deja vu joke in at one point). Upon meeting a scientist and his immense team of researchers, Acquefacques discovers he is indeed a character in a comic book and anxiously awaits the arrival of the book's last page, whereupon his final fate will be revealed.

So far, so familiar. There certainly have been plenty of self-referential American comics over the last thirty odd years to satisfy those who love a good breaking of the fourth wall.

Where Mathieu exceeds works like Animal Man, however, (and, just to make clear, I love Morrison's run on Animal Man) is in the way he breaks the fourth wall to examine how comics' manipulate time and space, a self-reflexive activity thatis not only startling in its creativity but also in the way it allows readers to examine their own relationship with what they read and how.

On page 41, of L'Origine for example, Mathieu has cut out the fourth panel from the book, giving readers a literal glimpse into Julius' future (or, once you turn the page over, his past). Beyond that though, he seamlessly integrates this window into the narrative, so the characters' dialogue on page 39, say, works equally well on page 42 ("I know. You already told me that" is Julius' response to the repeated "past" panel on 42).

I won't give away the ending of the book, on the off chance that this may someday see an English translation or you may manage to track down a French copy, except to say that it provides an utterly fitting and at the same time frustrating conclusion that again underlines the labyrinthine structures and mind-games Mathieu is attempting here.

Le Processus, the third book in the series, takes Mathieu's ideas about comics, time, space, bureaucracy, exestentialism and predetermination and expands upon it. Here, Julius awakens one morning, gets dressed and turns around to find ... an exact duplicate of himself, still sitting in bed.

A game of cat and cat begins, as one Julius chases the other across the city and into a doctor's office, where the first Julius has an appointment. It turns out, however, that he is five minutes early and thus is sent to the wrong room, where he is forced to undergo a bizarre experiment.

And it's here that the book really takes off, as Julius finds himself once more in his apartment, but with the ceiling missing. Climbing up, he discovers it is part of a seemingly infinite series of boxy apartments, all arranged in a tight grid-like structure (and I'll leave it to you to make the appropriate analogy here.

Eventually Julius comes upon "the vortex," and here Mathieu reaches near-divine inspiration, creating a die-cut spiral that opens up as you turn the page, whereupon you discover a two-dimensional, paper Julius interacting with a photographic, three-dimensional world. Sounds cool, right? And I haven't even mentioned how he later discovers the pages of Le Processus in his travels and literally trips into one of the pages (which we've already viewed, from a different perspective, before).

I fear I've made these books sound like dreary art-house, post-modern exercises, -- and to an extent they are -- but it would be a disservice to ignore Mathieu's sharp if somewhat tart sense of humor. His books are filled with a healthy appreciation of the absurd that echoes authors like Ionesco and Kalfka (take "Kalfka" backwards, spell it in French and you have Acquefacques). In L'Origine, for example, Julius visits some friends who live in an elevator shaft and must take apart the floor and hug the walls several times a day whenever the elevator takes a trip up or down. Why live there? Because it's one of the most spacious apartments in the city.

In the Acquefaques series, Mathieu engages in some delightfully bizarre world-building which he then proceeds to subvert and take apart as often as possible. The end result is one of the best metatextual comics we're ever likely to see. I know of no other works that makes me contemplate the medium's limits or delight in its unique abilities. Someone needs to translate these books. And fast.

For more information on Mathieu, I highly recommend tracking down issue #196over at Arthur magazine. I'd also recommend this site and this one. of The Comics Journal (the Dave McKean issue), which features Bart Beaty's excellent essay on this series, of which I probably cribbed from far too much. You can also read a rather recent profile of the artist