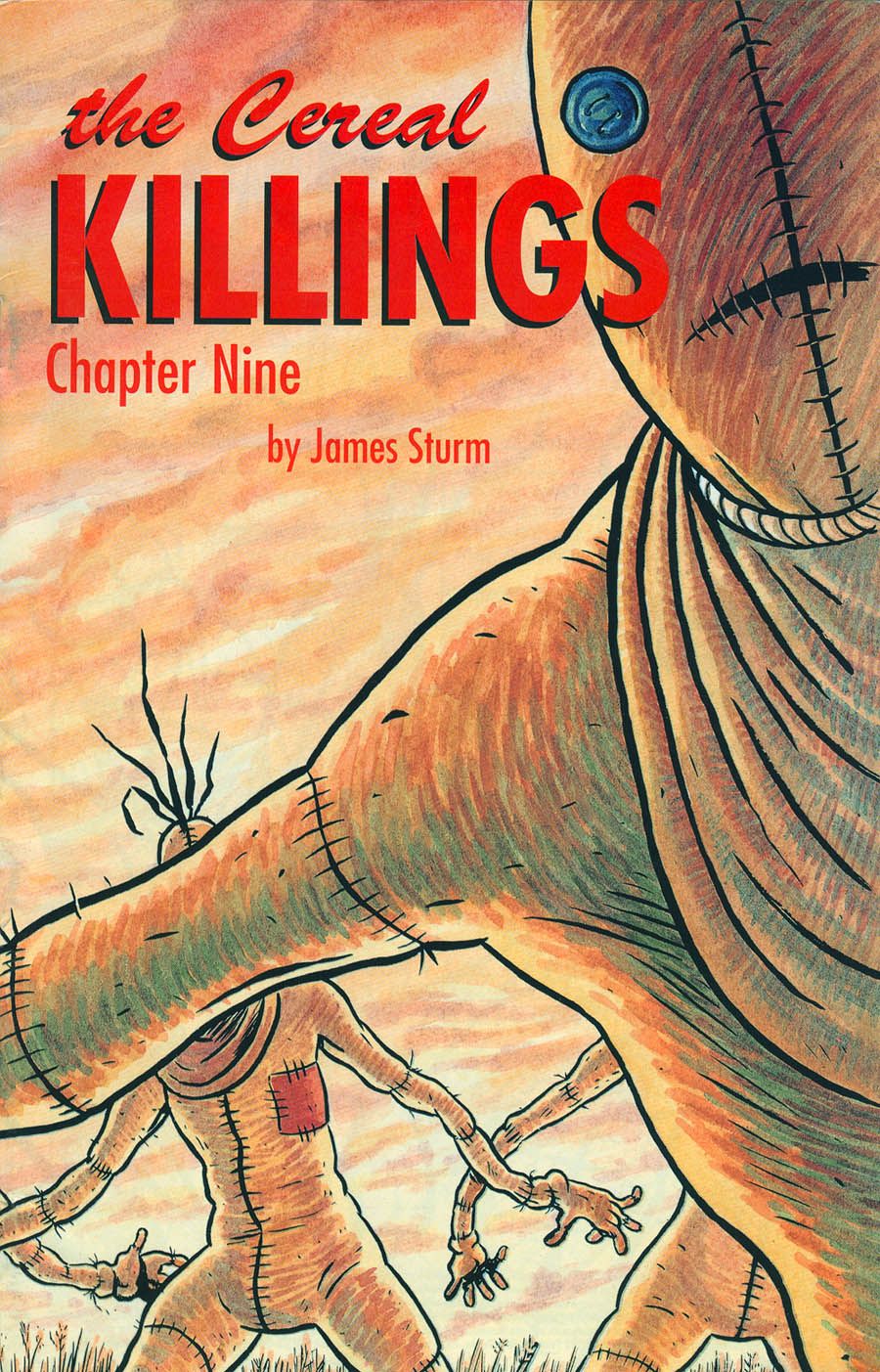

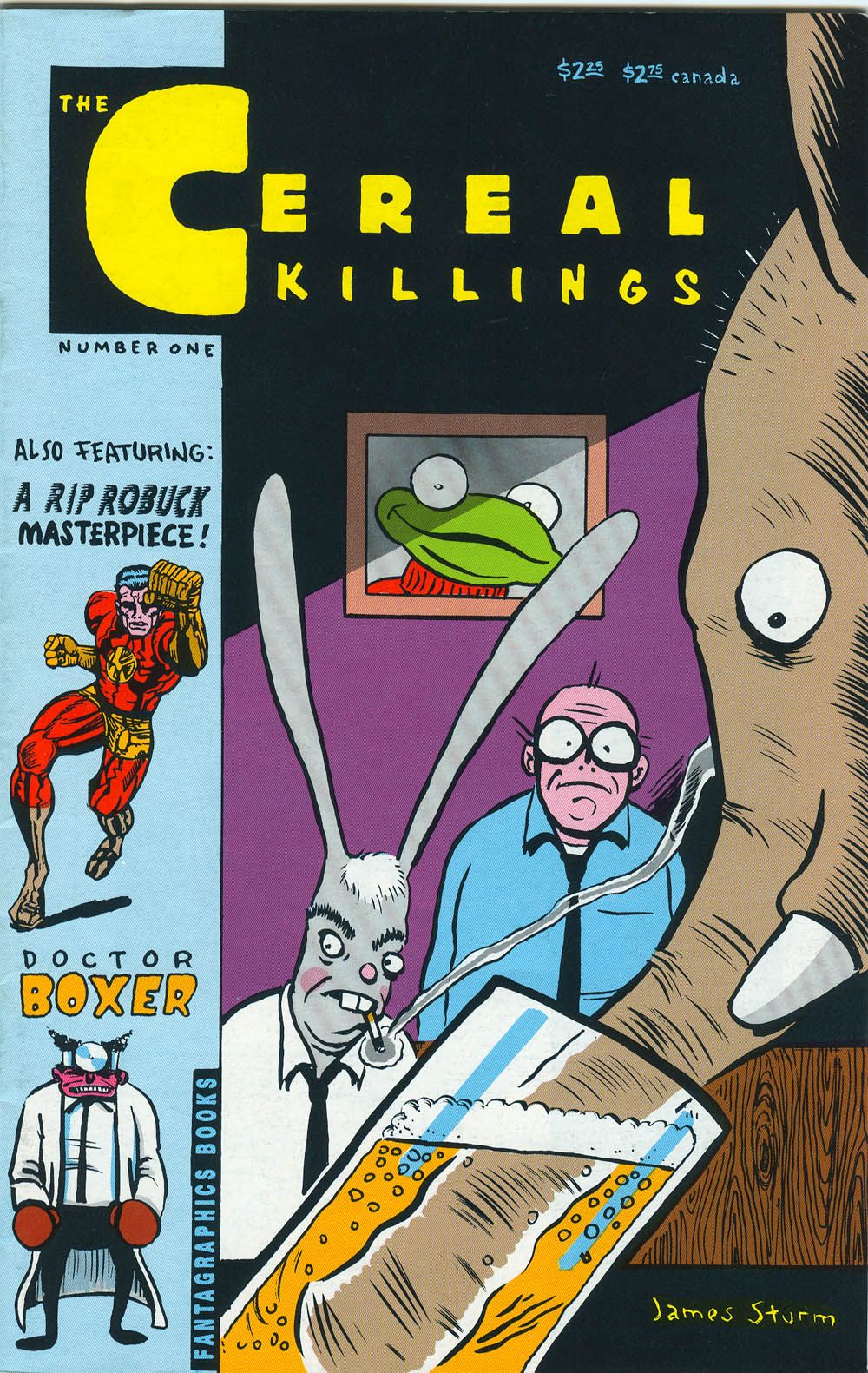

Perhaps this is the sort of work that pundits were fearing would die along with the indie comic pamphlet (which, Diamond policy or no Diamond policy, is pretty much six feet under by this point). An eight-issue mini-series, published by Fantagraphics between 1992 and 1995, The Cereal Killings is an awkward work at times, and betrays the youth of it's creator, James Sturm, both artistically and thematically. I get the sense, both from the work and in my limited conversations with Sturm, that he was often frustrated by its quality and indeed in his interview with Tom Spurgeon in issue # 251 of The Comics Journal he calls it an outright "failure." I can't help but wonder if Sturm had not serialized the story but attempted to publish it in one big graphic novel chunk if he wouldn't have simply abandoned it midway and moved on to something else.

That would be a shame because The Cereal Killings has a lot going for it. Despite its noticeable problems , it's an enjoyable, at times gripping work and is a seminal step in Sturm's development as an artist.

These days Sturm is perhaps best known for two things. One is his trilogy of comics focused on American history and culture, The Revival, Hundreds of Feet Below Daylight, and The Golem's Mighty Swing (all collected in D&Q's excellent James Sturm's America: God, Gold and Golems). The other is not-insignificant role in co-founding The Center for Cartoon Studies.

On the face of it, The Cereal Killings seems to be heavily influenced by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen, which, of course, had just wrapped up a few years ago and was, no doubt, still highly influential. You can even hear the pitch: "It's like Watchment, but with cereal mascots instead of super heroes!" It even opens with a death and hints tantalizingly at a murder mystery. But where Watchmen attempted to say something about the fascistic nature of superheroes, Cereal Killings is more of an examination of modern advertising, business and its corrupting influences.

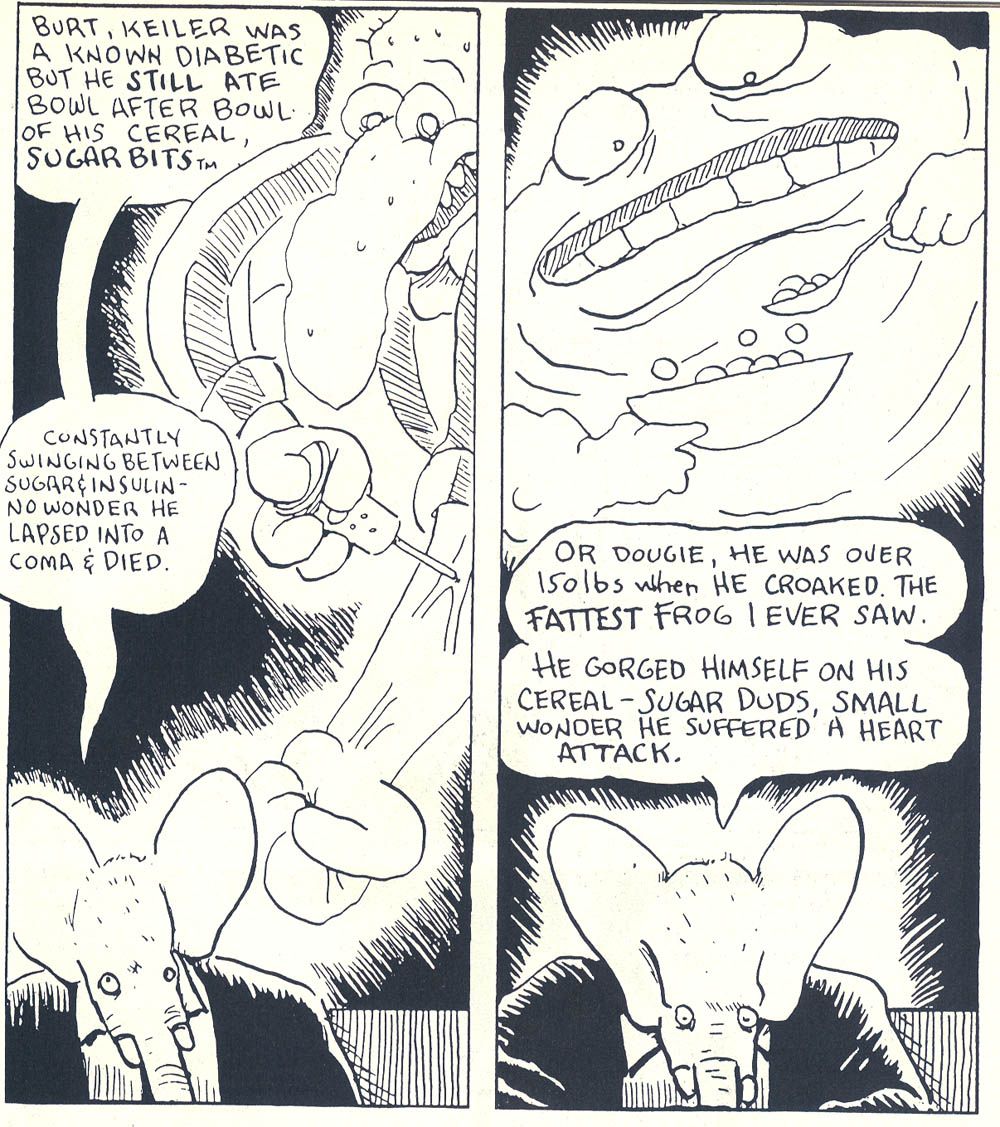

Killings creates a world where the pigs, elephants and rabbits that grace our cereal boxes exist in the "real world." The story, however, focuses on one of the more average looking folks, Carbunkle, a self-employed cereal marketer. He helped to serve as an agent of sorts for some of the most popular funny animals that appeared upon sugar-confected breakfast foods during the past few decades, including Dougie the frog and Keiler the cocoa bird.

These days though, the cartoon figures that once graced boxes of yore are no longer “in.” Now it’s all pop media stars and fads. The concept of a long-term figure that appeals to kids is dead. And so, it should be noted, are Keiler and Dougie, their one-note fame and debasement pitching what is essentially unhealthy product having seemingly driven them into early graves (it's not for nothing that Keiler is noted as a diabetic). The media have taken hold of the deaths and proclaimed that there is a “cereal killer” on the loose, leaving the public spooked and keeping boxes on store shelves. Belts, thus, are tightened, forcing more and more cereal icons out of work.

Carbunkle, meanwhile, blames himself for Dougie's death, for allowing the system to use and abuse his client and friend and doing so little to prevent it. In an effort at redemption, he dedicates himself to promoting “Corn Cereal,” a health food pitched by a scrawny scarecrow that had been reasonably popular back in the 1950s but was shelved for some mysterious reason. Carbunkle believes its revival will not only reaffirm a long-term relationship with consumers but in some inexplicable fashion make up for his past negligence.

But finding the scarecrow seems to be harder than initially thought. Anyone who might know anything about the mysterious figure is reluctant to divulge any information. What’s more, Snip the Elf, CEO of Kelcog, the largest cereal manufacturer in the country and former producer of "Corn Cereal," seems reluctant to bring the scarecrow back into the fold and is highly suspicious of Carbunkle’s motivations. The more stonewalling Carbunkle receives, however, the more determined he becomes to find the scarecrow. To him, the scarecrow is not just a mere pitchman; he is Carbunkle’s savior.

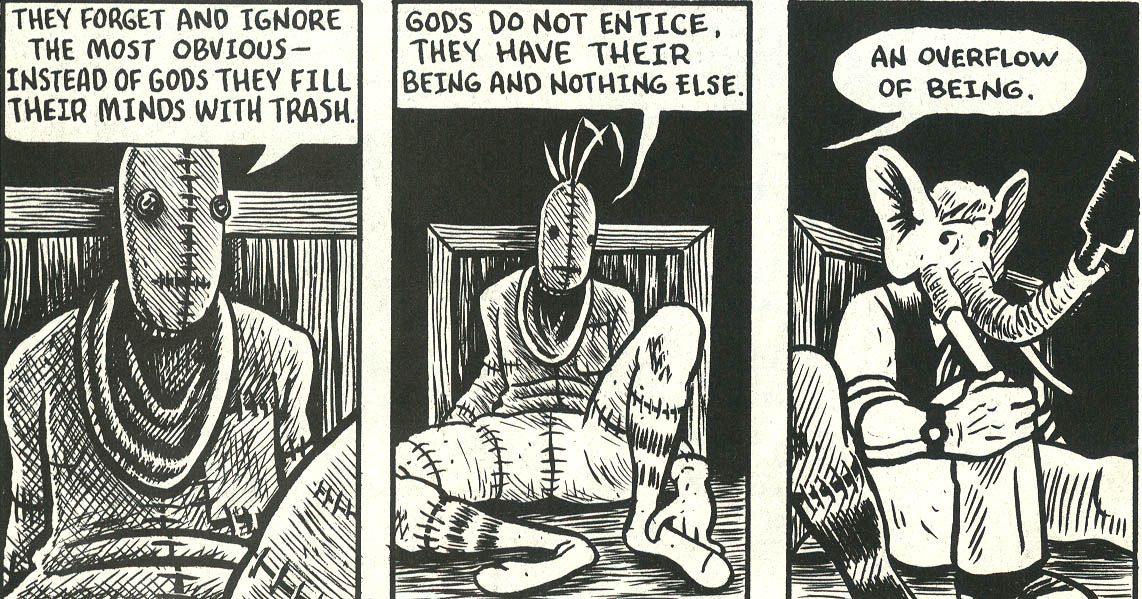

The book's flashbacks to the 50s do very little to discourage readers from attributing any sort of messianic allusions to the scarecrow (he never seems to acquire a name). For him it seems, making a healthy cereal is merely step one in providing a complete spiritual makeover. He even writes the copy for the back of his cereal box ("I've always felt that the words on the box were as nutritious as the flakes inside. The cereal is food for the body. The words are food for the soul.") And if you were to suggest that such a character would surely be on the fast track to martyrdom, well, I wouldn't discourage you from such a notion.

So yes, this is one of those comics where the metaphors are written large and loud, the most obvious one being food/physical health = spiritual well-being (Kellogg's, after all, started out as an outgrowth of Seventh-Day Adventist W.K. Kellogg's beliefs). The corporate cereal world, as portrayed by Sturm, is grim, backstabbing, crass and needlessly cruel. The men who inhabit it are hard-worn and bitter at best, drunkards and shells of their former selves at worst. This, of course, contrasts sharply with the scarecrow, who, obviously, represents the religious roots of the cereal industry.

Yet, while these types of allusions can seem obvious and sentimental at times. Sturm largely manages to make it work. He does a nice job of world-building, setting his characters in cramped business offices and diners. His characters, particularly the brusque rabbit Burt and the guilt-ridden elephant Schmedly, come off as knowable and well-written (Carbunkle, unfortunately, rarely moves beyond one-note status).

Ultimately, The Cereal Killings is a tale of how business and advertising can eat one’s soul. While cereal is the main product being proffered here, it could just as easily be shoes or washing machines. While Sturm obviously shows an affection and nostalgia for these cereal icons and the time period they lived in, he also subverts that nostalgia by showing how these icons are cogs in the machine of industry; hired workers who, like anyone else, can easily be fired and replaced. In doing this, he manages to show how ridiculous nostalgia for past pop culture and advertising moguls are in general, and how they are ultimately devoid of any meaning or spirit. Throughout the book, people betray friends, lie, and even commit murder for the sake of keeping their job at a breakfast food company of all things.

The other thing notable about Killings is Sturm's line, which starts out lean and sketchy in the first few issues and then becomes heavier and thicker in later issues (did he switch from pen to brush somewhere along the way?), slowly becoming more detailed and expressive in his renderings, especially with his characters. For process wonks, this series provides an up-close chance to see an artist slowly develop his style.

The Cereal Killings is far from perfect. The flashbacks between the 1950s and the present era often seem awkward and on first read it can take a page or two before you're fully aware of what decade you've been plunked into. The cast seems so large that certain characters, like Carbunkle’s wife, get lost in the shuffle. What's more, the series shifts awkwardly in tone from satire to tragedy, and some sub-plots (that afore-mentioned wife for example) aren't satisfactorily resolved.

Nonetheless, Cereal Killings suggested at the time that Sturm was capable of creating great stories, rich in character and emotion. If the comic is ulitmately an ambitioius failure, it's still a fascinating one, full of rich textures and undercurrents. You can feel Sturm playing with the form and there real moments of emotional power here, particularily in the final issue.

Perhaps The Cereal Killings is main appeal is to see how a now noteworthy figure learned his craft, but I think there's more to the work that that sort of surface engagement. Despite what Sturm says, I'd love to see it collected and put back out in print once more.