When Chris Mautner asked if I'd be willing to take a crack at writing the "Collect This Now!" column during my guest-blogging stint, I said yes precisely because of this book. And when I informed him of my intentions, he said he was glad, because Marvel hadn't yet been tackled in the column.

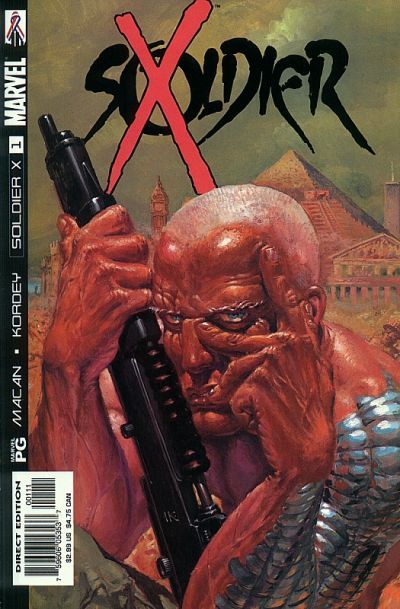

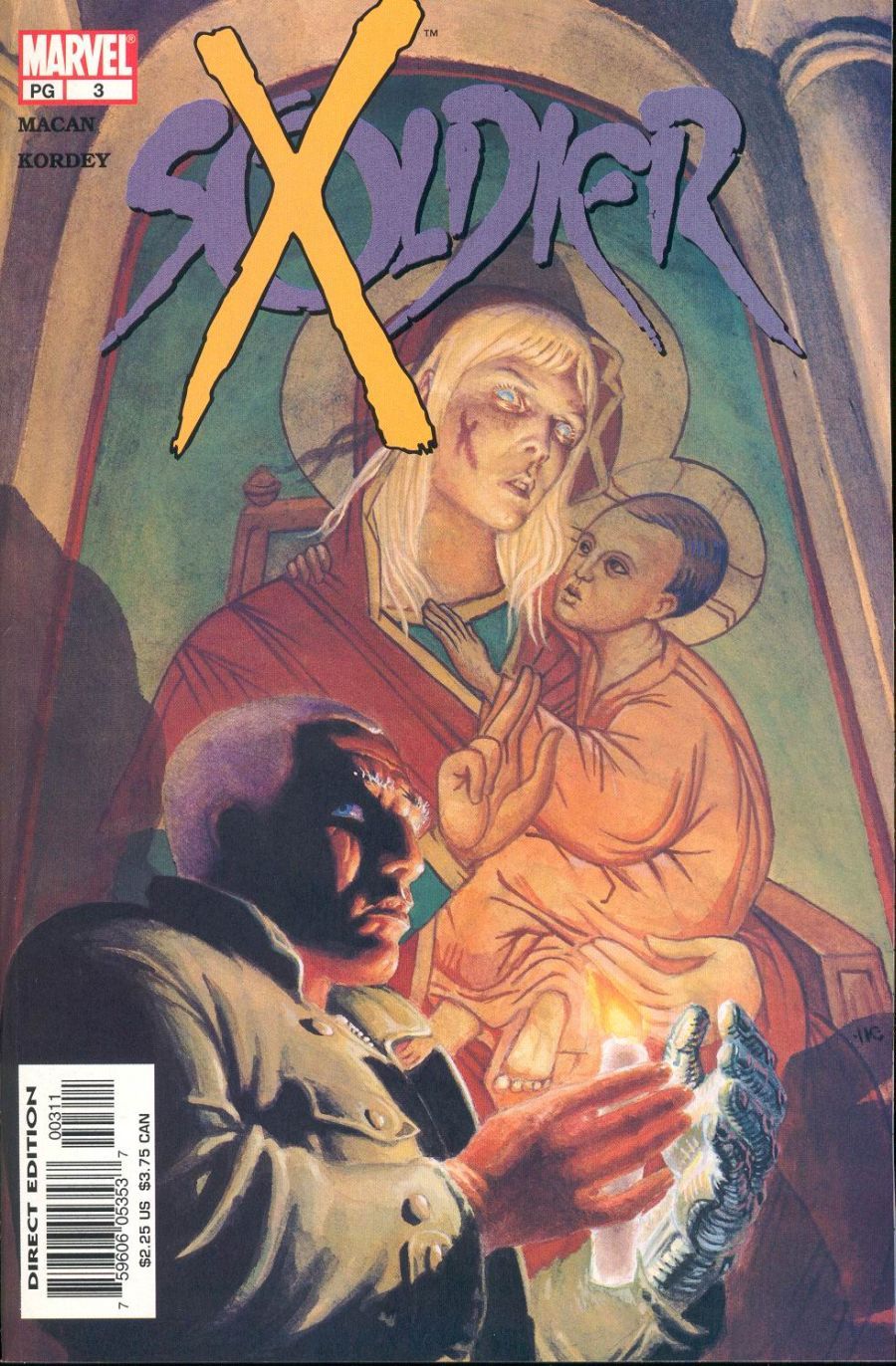

This stands to reason, given that we're now seven years or so deep into Marvel's "collect-everything-we-publish" plan — what's left to collect? The answer is Soldier X. Written by Darko Macan and illustrated by Igor Kordey, this short-lived, Cable-starring series is wild, weird and wonderful, even by the far-out standards of the late Bill Jemas era. That's probably what dooms it to TPB-less obscurity, but it's also why I'm still so fond of it.

Soldier X's roots lie in a 2001 revamp of the long-running Cable series. Back in those early "Nu-Marvel" days, the '90s nostalgia that has since swept superherodom was far far away, and characters like Cable couldn't shake the stink of shoulder pads and endless crossovers from the bad old days. Writer David Tischman's solution, beginning with Issue 97, was to give the hero also known as Nathan Summers new relevance by taking this soldier from the future and making him a soldier in the present, teleporting into various real-world hotspots and intervening on behalf of the innocent and oppressed. This, Cable claimed (or at least the narration claimed on his behalf), would help the world avoid the nightmarish future Cable himself came from. Joining Tischman in this endeavor was artist Igor Kordey, a Croatian veteran of the Balkan wars whose personal experience and rough-hewn, inky art gave an air of authenticity to a project that could seem like exploitation in lesser hands.

But this new direction — anticipating though it did Marvel's linewide move toward the militarization of superheroes later in the decade — lasted all of two critically acclaimed but poor-selling story arcs, the latter of which, a story about attempts to use sci-fi cloning and biowarfare to tip the balance of the ethnic conflict between Albanians and Macedonians, was co-plotted by Kordey himself. Then Tischman left -- decamping for DC, if I recall correctly -- and Kordey's fellow Croatian Darko Macan took the helm with Issue 105. That's when things got weird.

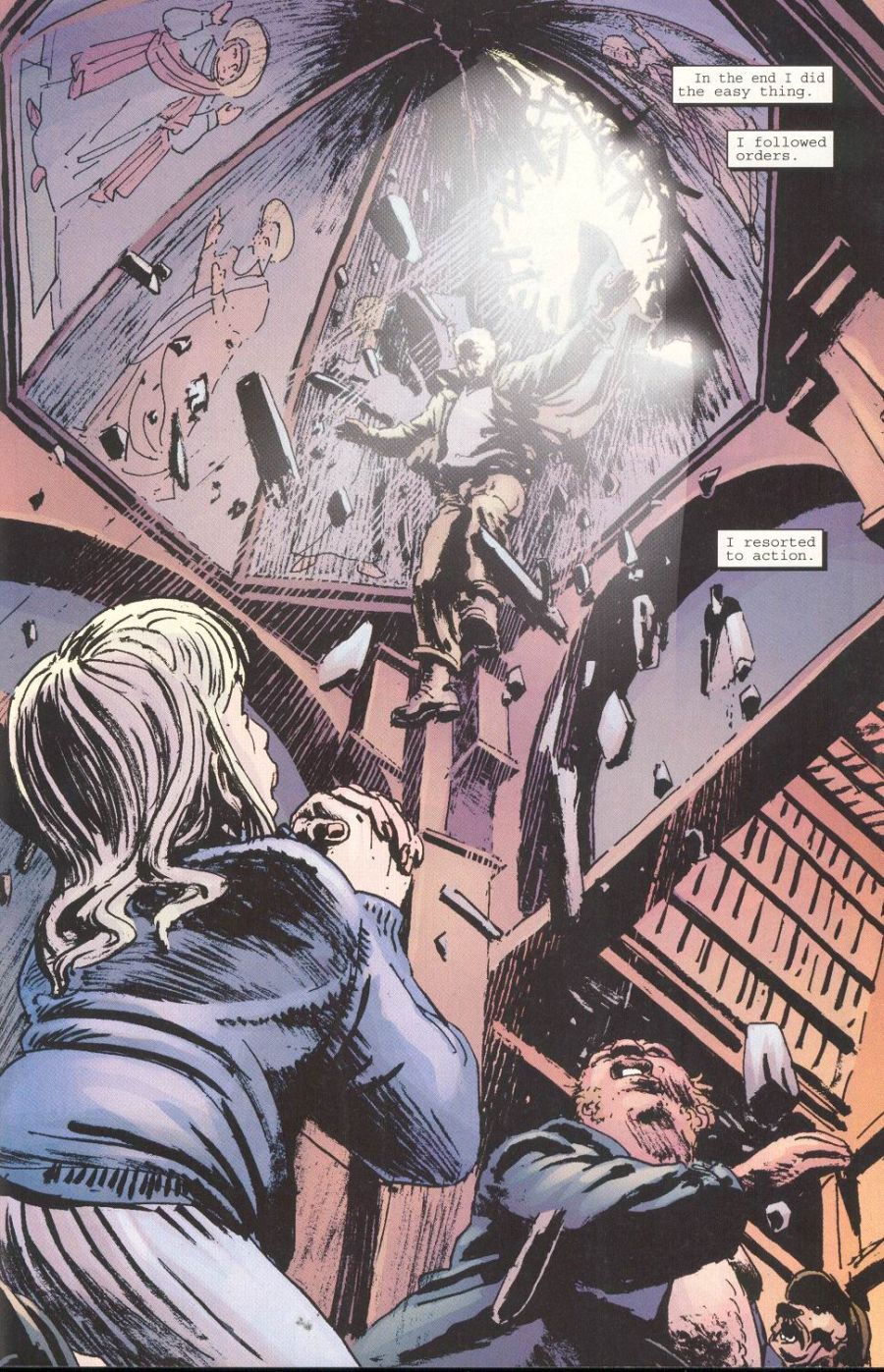

Beginning with Kordey's co-writing credit on Tischman's final issue, #104, suddenly the book began directly addressing the futility of using violent conflict to solve violent conflict — a stunningly direct rejoinder to the "realistic" approach Tischman instituted. Key to the book's new mission was an explosive increase for Cable's telekinetic and telepathic powers: Having purged his body of the techno-organic virus that had long plagued him in a Tischman/Kordey issue that took place during Marvel's "'Nuff Said" silent-comics stunt month, Summers reached nearly Phoenix-like power levels, which alternately prevented him from using his powers lest they get out of control, or caused them to erupt despite his best efforts, threatening friend, foe, and noncombatant alike. As the story goes, this leads Cable to question the very nature of his newfound mission: "I destroy buildings, I raze mountains, and what have I accomplished? Nothing."

When Macan took the writing reins in #105, he used the Cable series' three remaining issues as self-contained set-up stories for the Soldier X series to come: #105 showed Cable losing control of his telepathy and accidentally mindwiping an arena full of spectators at a lethal mutant fight club in Rio; in #106 (featuring fill-in artist Mike Huddleston) his massacre of murderous nuclear arms smugglers in Kazakhstan enabled sinister anti-Cable forces to frame him for the murder of a S.H.I.E.L.D agent; and in #107 we meet Jackie Singapore, the megarich mutant slated to be Cable's new big bad. Then the series was retitled Soldier X (similarly, Deadpool became Agent X, under Jemas's rationale that normal people don't know who Cable and Deadpool are, but they do know what a soldier and an agent are) and relaunched with a #1, and Macan and Kordey were truly off to the races.

Soldier X announces its intention to aim for the heart of Cable's dual role as superhero and soldier right from its first issue. On the surface it's one last scene-setting one-shot, reintroducing Cable's intrepid-reporter confidant Irene Merryweather (in a framing story set an unexplained two years in the future, no less) and Yoda-knockoff mentor Blaquesmith. But it prominently, and with little explanation or reason why, co-stars a pair of time-displaced warriors from centuries past (an Egyptian charioteer and a Polish hussar), now stranded in modern-day Egypt. The Hussar describes their plight thusly:

Wars, right?! Again and again in all times and all places! And what if it is always the same war?! One never-ending war, the blood wind blowing through the tunnels of time? And us, soldiers, getting caught in its draft, fighting in one war--finding ourselves in another?

But when Cable questions this possibility, the pair offer a different perspective: "Well, perhaps we only dreamed our previous lives," admits the Hussar, to which the Egyptian adds, "Or perhaps we are simply madmen, visiting the graves of people we pretend we knew." The eternal nature of conflict, the absurdist nature of the way people are caught up in it, the embrace of dreams and madness as maybe the only way to make sense of it all — there's Soldier X in a nutshell.

This leads to the book's one and only full story arc, starting in issue #2. Blaquesmith, a flippant little hedonist who might remind today's readers of Ed Brubaker's Master Izo character in Daredevil, assigns Cable the task of rescuing a Russian peasant girl with a mutant healing power. When Cable travels to her backwater village, he discovers an array of equally unpleasant persons vying for control of her gift. Her domineering religious-fanatic mother seems to be suffering from a martyrdom-centric version of Munchausen-by-proxy syndrome, pushing her daughter's gifts to their limits in hopes to go down in history as the mother of a saint. The local clergyman seems more legitimately moved by the possibly divine nature of her gifts but equally indifferent to her suffering. Her cowardly father encouraged her exploitation because of the gifts of money and vodka that the faithful tended to throw his way, but fled either to seek help when things went too far or to escape the Armenian mafia who became outraged when they learned they weren't getting a cut of this action. The girl herself, named Magdalena in a fashion typical of Soldier X's subtlety level, recovers from death by leeching off some of Cable's extraordinary power, then becomes a selfish, creepy parasite herself. The aforementioned Armenian mafiosi, a callous collection of lollipop-sucking sociopaths, eventually show up too, as does the real star of the show: Geo, another metal-armed mutant who's been blowing up American fast-food franchises in a battle against globalization and, of all things, "complacency." His deranged, all-caps monologues about his quixotic battle to live free of any kind of control — mixed in with a grudge against Cable for landing any mutant with one metal arm on the most-wanted list — are hilarious, yes, but they also provide a stark contrast with Cable's pseudo-Eastern Askani religion, filled with platitudes about accepting one's fate; they're among Macan's best moments in the series.

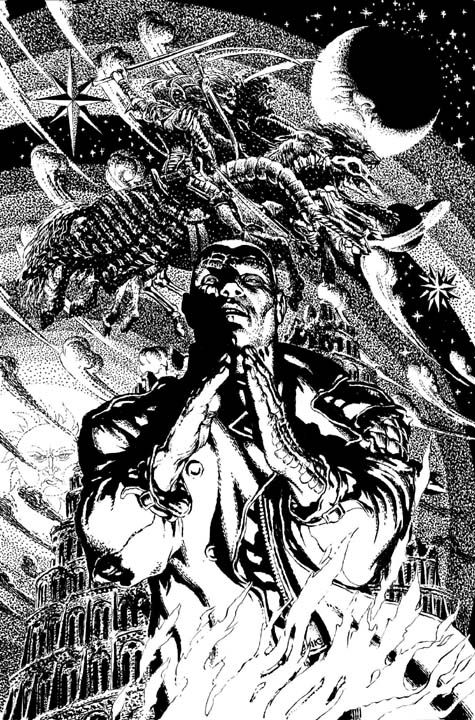

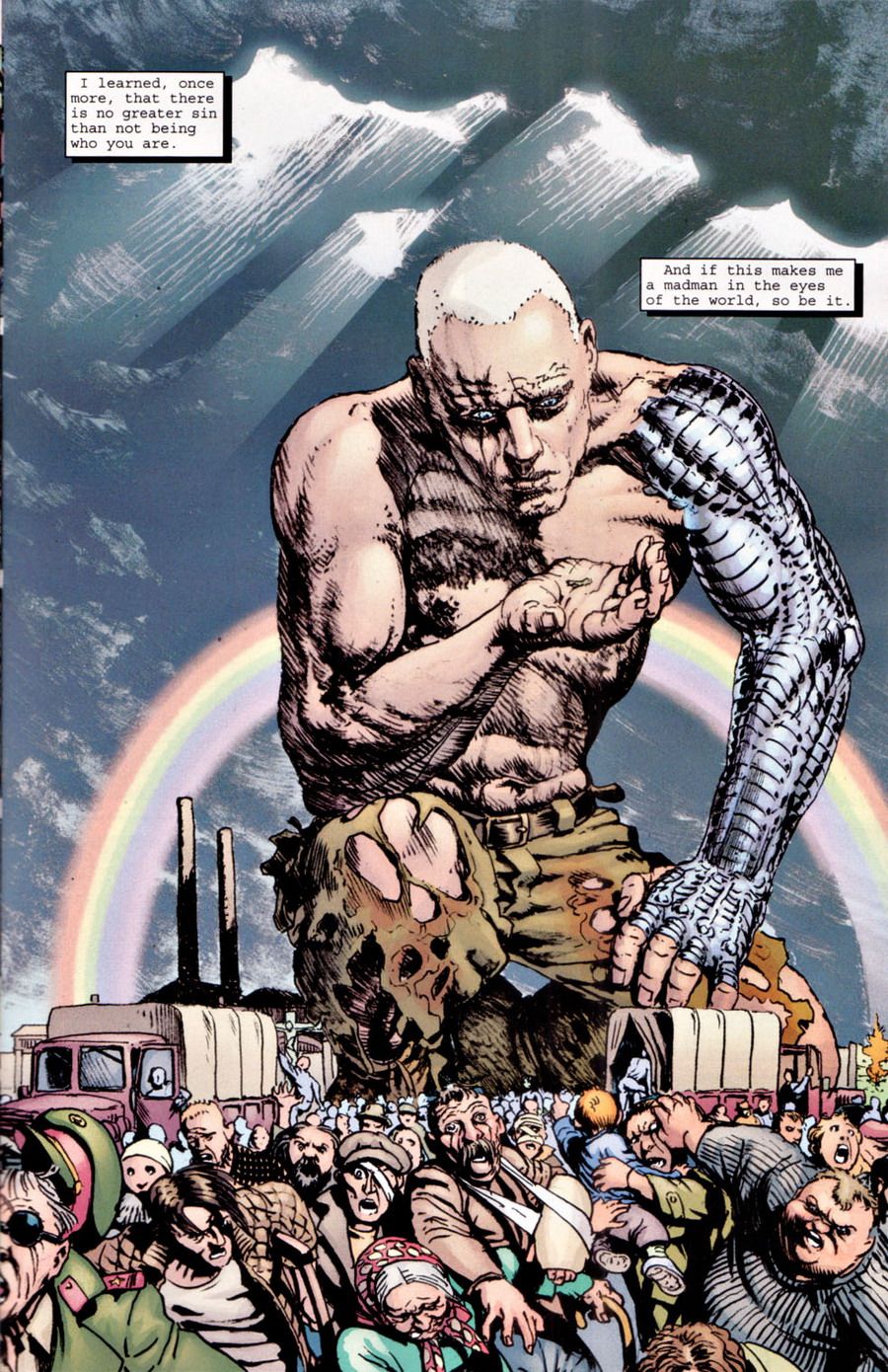

Kordey, for his part, gets to shine when showing Cable's increasingly outlandish abilities. Kordey's the kind of artist you could see showing up half a decade later to illustrate some First Second graphic novel about the Tamil Tigers or the janjaweed militias, but instead he ended up at Marvel, and the fact that he could handle both the realistic ethnic-conflict trappings that remained from Tischman's run and the spectacular superheroics required by Cable's power upgrade with equal aplomb, often at the same time, is a testament to how perfectly this assignment suited him. His Cable flies, he hovers, he heals the dead, he gets shot full of holes and recovers like an old-school Wolverine, he does battle in an abandoned factory called Saint Lenin "where a mad artist used to work on blending Orthodox and Communist iconography," he engages in an increasingly pointless series of slugfests with Geo, he transforms a man into a bat, and in the series' single most memorable image, he grows into a giant to frighten off the rampaging peasants who've torn Geo to shreds. It's the superhero as absurdism, a series of cascading visual and narrative non sequiturs meant to reveal the ridiculousness of the notion that a man could prevent his own violent future by wreaking violence in the present, and it's glorious to behold.

See what I mean?

I don't suppose you need me to tell you that this was not what almost anyone, least of all Marvel, was looking for. Following the conclusion of the Russian arc, the Macan/Kordey team (with editor Andrew Lis seemingly playing a key support role) squeaked out a couple more issues that bear the air of knowing their time was at an end. Issue 7 reveals that Blaquesmith was actually just an impostor hired by the now-moot archvillain Jackie Singapore, but who is now so impressed by Cable that he'd like to become his disciple. Issue 8 flashes forward 2,000 years to a world governed by Cable's Askani philosophy ... where, of course, most people are just as violent and small-minded as ever, and where the only real act of superheroism is to volunteer to die in the place of another. Lots of loose ends are left dangling, from Singapore's dog-that-never-barked act to fake-Blaquesmith's rushed reveal to a go-nowhere subplot involving a pair of ne'er-do-well S.H.I.E.L.D. agents assigned to take Cable down to the disappearance from the title of the Tischman-introduced antagonist Goldberg to the reasoning behind the Irene Merryweather framing story's two-year jump. The fourth wall is broken with impunity, from recap pages in which characters directly address the audience and say "this is the recap page," to a splash page of characters from throughout the Kordey era mourning Cable's death whether or not they themselves had died during the series, to a final splash page of the creative team waving goodbye to us, even to direct mockery of the linewide recap-page edict itself.

And then they were gone. Kordey soon left Marvel altogether in a storm of criticism and recriminations over his work on Grant Morrison's New X-Men, and though I'm not 100% sure, I believe this was Macan's last Marvel work as well. The series continued in fairly perfunctory, more traditional fashion for another four issues before the plug was pulled, not unlike how New X-Men lurched on for a brief while like a chicken with its head cut off after Morrison's abrupt departure. But it's what Kordey and Macan left behind that matters: a document of the rise and fall of a strange and freewheeling era at the North American comics industry's biggest company, as radical a reimagining of one of that company's core concepts as the far more ballyhooed work of Morrison and Quitely or Milligan and Allred, and as strangely lyrical a superhero comic as you're ever likely to find.

It belongs on your bookshelf.

(For more on the series, see Joe "Jog" McCulloch's excellent essay at the Savage Critic(s).)