Like JK, the recent discovery of the third issue of Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz's Big Numbers put me in mind of another much ballyhooed, but equally hard to find Moore series, Miracleman.

Of course, as with Flex Mentallo, there's little chance this series will ever see print, at least for the nonce. Neil Gaiman, Todd McFarlane and a host of other lesser mortals have been arguing in court and other areas over who owns the character for over a decade now, and resolution seems as distant as the Orion belt.

The fact that the original Eclipse Comics trades and pamphlets are either a) tough to find or b) very expensive only makes the absence of a new collection only more irksome, as Miracleman still holds up remarkably well, despite having to constantly live in the shadow of its bigger and more popular brother, Watchmen.

Miracleman (or Marvelman as he is known in his native U.K. More on that in a minute) started out in 1954 as a blatant British rip-off of Captain Marvel (the guy who says "Shazam," not the Kree warrior) -- a boy reporter named Michael Moran who only had to say his magic word, "Kimota" (pronounce it backwards, as I said, the character wasn't particularly original) to turn into a magnificent physical specimen with extraordinary abilities.

There's a reason for that bit of copycat chicanery, as only a short time earlier Fawcett Comics, owner of the Big Red Cheese, had folded up shop, unable to win their lengthy legal battle against DC (then National) who felt that the Captain was a bit too similar to their own man from Krypton.

And yes, there is a certain irony in a fictional character being born as the direct result of a lengthy lawsuit and then decades later prevented from continuing his adventures due to another bit of legal snarl.

Anyway, the folks who had been publishing Captain Marvel's adventures in Great Britain didn't want to lose their star player, so they hired writer-artist Mick Anglo to create a substitute. Thus was born MM, and his adventures continued until 1963, when the series came to a close.

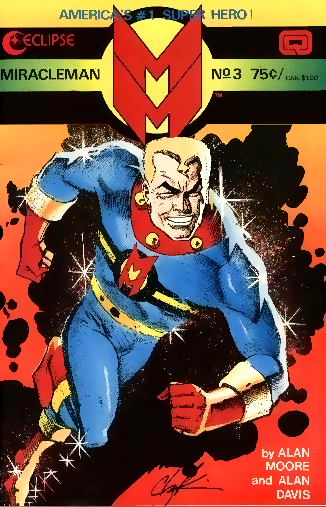

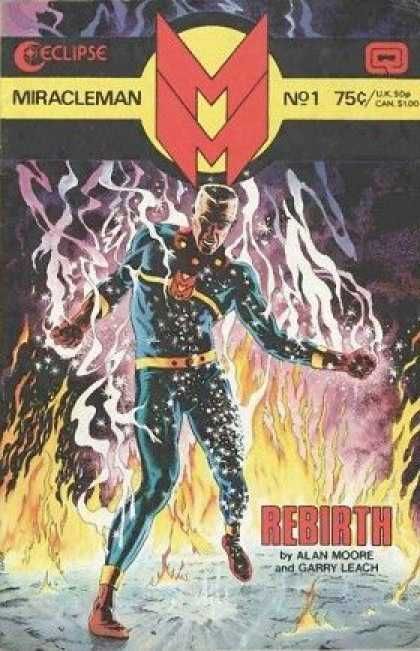

Enter Alan Moore, who in 1982 was hired by the new Warrior magazine, along with artists Gary Leach and Alan Davis, to bring back and re-interpret Marvelman. (The character became Miracleman, at least in the United States, when Marvel the comic book company objected to the title. Did I mention that this character had a long and confusing history of legal trouble?)

Moore, Davis and Leach's vision fit perfectly in the new gritty, more "realistic" framework of fantasy stories that Warrior and other comic magazines were creating. The story opens with a grown-up Moran, now pushing 40. Having completely forgotten about his years as a superhero, he works as a freelance reporter, is frequently depressed and given to migraines. Then, while on assignment, he gets caught in the middle of a terrorist raid, remembers his magic word and transforms once again into Miracleman, ready to rid the world of evil.

But of course, it's not nearly that simple is it? The memories that Moran has of his youth and origin are suspect to put it mildly. The seemingly cartoon villain he believed to be his nemesis was the force responsible for his creation and has returned to finish his experiments. His former teen-age sidekick, Kid Miracleman, has grown up to be the most psychotic and dangerous being alive. Oh, and his wife is pregnant.

These days, this sort of "everything you know is wrong" character reinvention has become a cliche in and of itself, but it's important to remember that it was a relatively new idea when Moore came along. More significantly, Moore's ultimate aim with the series is a lot grander and philosophical than merely shifting the tone and upping violence quotient a to fit a more cynical readership.

As with Watchmen, Miracleman explores the idea of what life would be like in a world with god-like superheroes. Parallel themes of the corruption of power, individual responsibility and such abound. As with Ozymandias, Miracleman does indeed ultimately save the world, reshaping it into a divine utopia, though not without a severe cost.

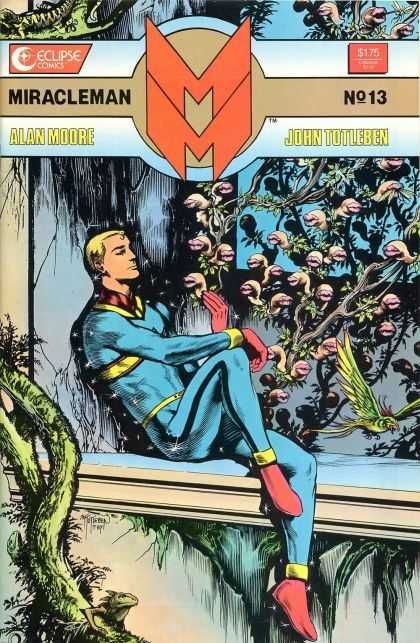

Because of the similarities, Miracleman tends to get seen as Watchmen redux, even though it was first down the pike. Certainly it's not as tight a story -- it's a sprawling work that took several years to complete and had a revolving door of artists. In addition to Leach and Davis, Rick Veitch and finally John Totleben made significant marks on the series.

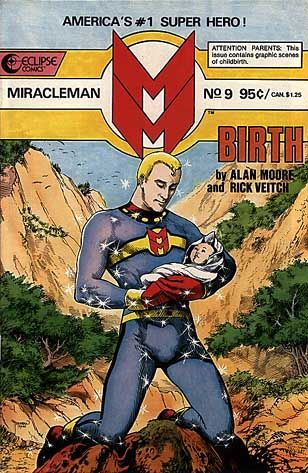

But if Miracleman lacks the clocklike craftsmanship of its big brother, it nevertheless remains a compelling work, full of stunning, indelible sequences and characters. At times it's almost operatic whereas Watchmen is more like a concerto (my knowledge of musical terms is pathetic, so I apologize if I just offended someone with that anology). The birth of MM's baby, which fell under a bit of controversy at the time for Veitch's uncensored depiction of childbirth, or the death of intelligence spook Evelyn Cream are but two examples.

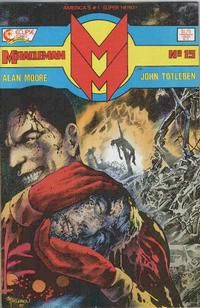

If Miracleman is remembered for anything, however, it's issue #15, easily one of the darkest, most violent comics not only in Moore's canon but quite likely in the medium ever (and I've read S. Clay Wilson). In the issue, a psychotic Kid Miracleman battles his former partner and friends, leveling London to the ground, with little left to the imagination as to the type of carnage wrought. Totleben's art is chaotic and gruesome, with wreckage, severed limbs, dead bodies and other horrors crowding and choking each page.

Again, it's a distinct rejoinder to the fan's wish/wonderment of "what if superheroes really existed." Well, Moore reminds us,they'd lay to waste the world around you. They'd destroy everything you ever believed in and replace it with a world that, while it might be filled with wonders and triumphs, would deny you your basic humanity. Beyond simple genre subversion, though, Moore is explicitly pointing out -- as he did from a different perspective in V for Vendetta 00 the danger inherent in attempting to create any utopia, superpowered or otherwise.

After wrapping up the series with issue #16, Moore handed the reins and (what he though were) his rights to the series to Neil Gaiman, who picked up and poked and prodded at what Moore had left behind, sometimes brilliantly. Sometimes not so.

Gaiman never got the chance to finish his tale due to the afore-mentioned legal troubles, but really, apart from idle curiosity, I don't mind so much. Moore arc felt complete in a way that few authorial "runs" on a comic book do. That final two-page spread, with a slightly uneasy Miracleman surveying his empire is a fitting end and the only conclusion I'll need. I just wish it were readily available, in print at least, so that others could savor it as well.

For more on Miracleman, visit here, here, here and here. You may also want to buy a copy of this.