This, perhaps, is an obvious selection for this column. Mayhap too obvious? One could, for instance, argue without a lot of brain-strain that if this feature has any sort of patron saint, it is without a doubt Flex Mentallo.

Part of that is because the chances of Flex Mentallo ever being collected in trade again are somewhere between slim and none, as my dad used to say. That in turn is largely because of an ugly lawsuit thrown at DC by the Charles Atlas folks. Even though DC got the suit dismissed, they've been reticent to get this series back in print. Rumors suggest everything from promising the Atlas people it would never see the light of day again to lackluster Doom Patrol sales squelching any plans.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. A bit of backstory is, no doubt, in order.

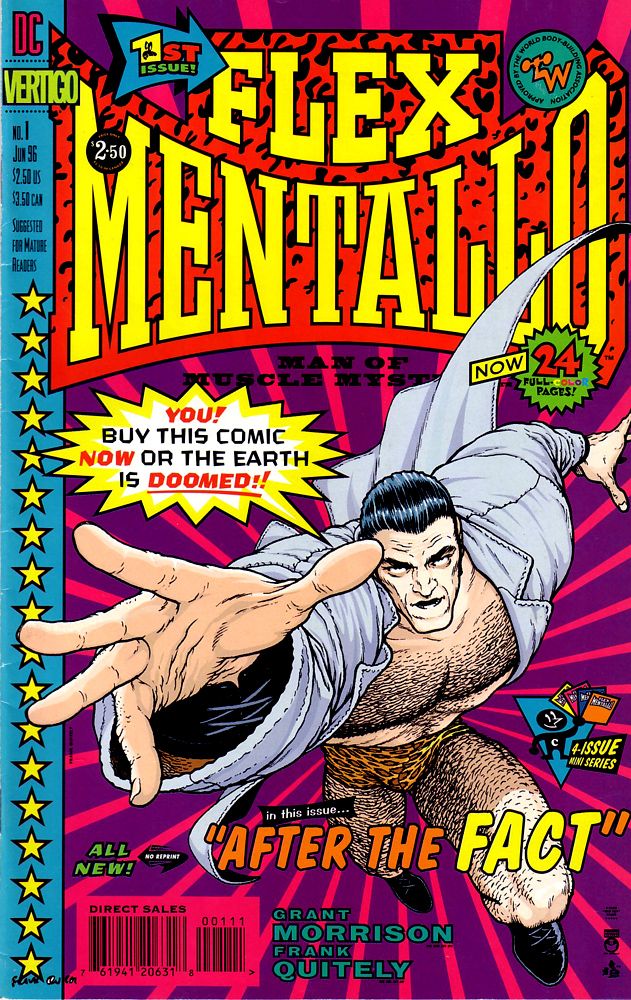

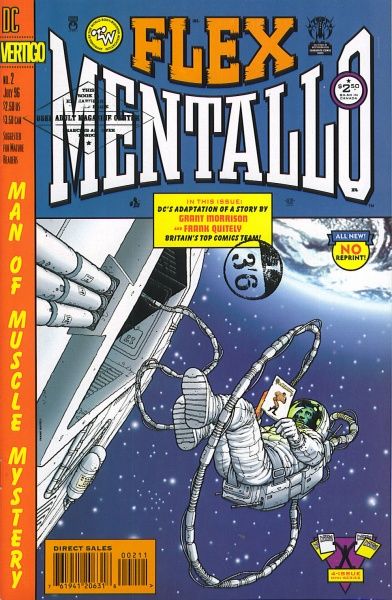

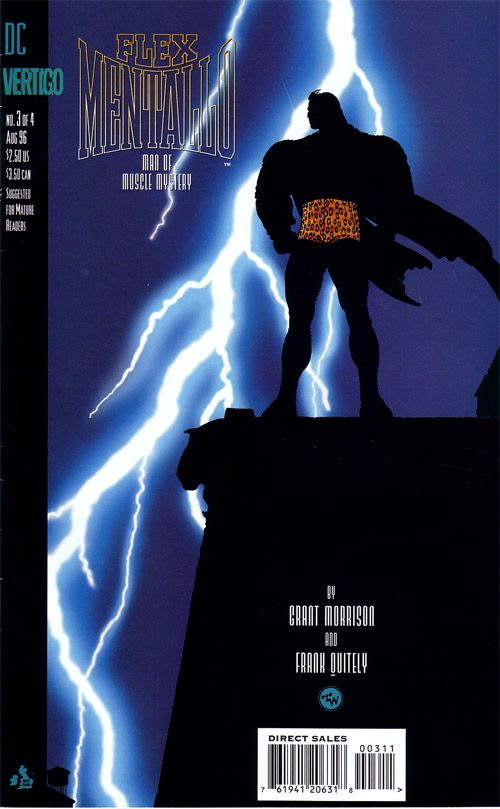

Flex Mentallo was a four-issue mini-series published by Vertigo Comics back in 1996. It was written by Grant Morrison and drawn by Frank Quitely, a team more recently responsible for All-Star Superman, a series acclaimed by every Internet comics pundit from here to Earth-7 (including yours truly) as the best superhero saga in recent memory, amen and hallelujah. Flex Mentallo is a better work though, perhaps because it isn't as reliant on the many decades of Superman mythos and can thus move about a little more freely.

Flex Mentallo, better known as the "Man of Muscle Mystery" first appeared in Grant Morrison and Richard Case's Doom Patrol #35. His secret origin was a very amusing parody/pastiche of those classic Charles Atlas ads from way back when, hence the lawsuit. His super power involved flexing his muscles, the vibrations of which could knock people over, tear apart floors or even turn the Pentagon into a circle. (I find it interesting that, despite his muscles, Flex is a hero who largely eschews violence. He doesn't punch or kick to fight evil. He simply poses.)

Eventually in the series it was revealed that Flex was created by a kid named Wally Sage whose latent psychic abilities managed to bring flex out of Sage's crayon-colored page and into the real world.

In Flex Mentallo the mini-series, we find Flex both on the trail of an odd terrorist group known as Faculty X, known for planting bombs that never explode, and his former comrade The Fact, whom Flex suspects of having entered the "real world" just as Flex did.

Co-current to that story is that of a young rock star named Wallace Sage, who has apparently taken a shitload of drugs in a suicide attempt. As he spirals into oblivion, he calls a suicide hotline, mainly, it seems, to talk about superhero comics.

So wait a minute, is this the same Wally Sage that brought Flex to life (at one point the singer calls sage his "secret identity")? Is he somehow existing in the same world as Flex or in an alternate universe? Which is the "real world"? Is everything just happening inside Wally's head? What exactly is going on?

Morrison and Quitely keep the reader guessing as much as possible, constantly shifting and overlapping scenes between Flex and Wally. Thus, the whole comic at times feels like a bizarre hallucination, though a glorious, eloquent one.

But there's more to Flex Mentallo than post-modern metatextual hoo-hah and fourth-world breaking (though I should note I'm a sucker for that kind of stuff and there's enough of it here to keep schmoes like me happy for aeons). This is, perhaps the greatest mash note to the superhero genre ever written. These pages are Morrison's manifesto and drive just about every single thing he's written since, particularly his work for DC, like Final Crisis and Seven Soldiers.

As has been noted elsewhere (see below) the series can be divided into four homages to specific periods of comic book history: Issue one, for example, references the golden age. Issue 2 is the silver age and issue three comments on the "grim and gritty" era with rather pointed barbs aimed at Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns.

And it's here that Morrison's strongest theme shines through. Disdainful of the attempts at "realism" that have dominated the genre in this modern age ("Only a bitter adolescent boy could confuse realism with pessimism," one character intones), Morrison spends the bulk of this and the fourth or "new age" issue making the case for the notion of superhero comics as a potentially positive, transformative experience, a way to acknowledge the great potential buried within each of us and inspire us to move beyond despair and ennui. Sound sappy? Sure, but Morrison and Quitely make it believable and compelling. I was going through my own "I hate superheroes phase" when I read this series, and it went a long way towards helping me get over my snobbish attitude.

There are many layers and different readings to be mined out of Flex Mentallo but I really don't want to delve too deep into them at the risk of spoiling your reading experience if you haven't discovered the series yet. (Though good luck if you haven't. My understanding is finding back issues is tricky and expensive proposition. Bittorrent seems to be most folks' best bet).

For me, Flex Mentallo remains Morrison's best and most significant work so far. It's really a crime this series hasn't been collected up till now.

For more information on Flex Mentallo, see here, here, here, here, here, here and here.